Ryan Tudhope worked for The Orphanage and ImageMovers Digital on projects like HELLBOY, SIN CITY, PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: DEAD MAN’S CHEST or MARS NEEDS MOMS. In 2011, he founded Atomic Fiction with Kevin Baillie and supervises the effects of films like JACK AND JILL and UNDERWORLD AWAKENING.

What is your background?

My career began in Seattle where my business partner Kevin Baillie and I grew up. In 1994, when we were in a ninth grade drafting class, we discovered Autodesk 3D Studio release 2 for DOS. We had just seen JURASSIC PARK and were fascinated by the ability to create three-dimensional renderings of anything our mind could think up – space ships, robots, alien worlds, cities, etc. Our drafting teacher, Rick Nordby would allow us to stay there until the alarms went on, and even convinced the school to lend computer workstations to us over our summer break so we could practice.

After creating several short films for our school’s Homecoming assemblies, we networked through a series of paid gigs, and eventually landed jobs at Microsoft at the age of 16. There, Kevin and I were supported by a manager named Mark Kenworthy, who enlisted us to create another animated film that would be used to demonstrate the capabilities of Active X.

Meanwhile, The George Lucas Educational Foundation (GLEF) was scouting high schools around the United States, searching for schools and students that were making the connection from school to career. Kevin and I were “discovered” and eventually featured in a national documentary narrated by Robin Williams called LEARN AND LIVE. It was our big break; George Lucas and his producer, Rick McCallum would see the footage and invite Kevin and I to stay at Skywalker Ranch for a weekend, tour ILM, meet several VFX legends and catch a glimpse the pre-vis work from STAR WARS: EPISODE I. At the time, in 1996, we were two out of a dozen people who had seen the “Pod Race”.

After a whirlwind tour, Kevin and I went back to Seattle, but we made it our mission to get jobs at Lucasfilm. And so, with a lot of hard work, persistence and many emails, we got hired on the JAK Films pre-vis team a week after our High School graduation, at the age of 18. There, we had the opportunity to work with one of our biggest heroes and design thousands of animatics for the film.

After EPISODE I came out, Kevin and I joined The Orphanage as the company’s first two employees. We helped grow the studio to over 200 employees at its peak, and since we were there from the beginning, our careers grew quickly due to the company’s rapid growth, our hard work and the support of the company’s founders.

When The Orphanage closed its doors, I was invited into a Disney-backed company called ImageMovers Digital. Kevin had already been there about a year, and we worked on several projects before that studio closed at the end of 2010. The experience had a big impact on us since it gave us an opportunity to interact and supervise with a “big shop” pipeline at our fingertips.

Can you tell us more about the creation of Atomic Fiction?

We felt there was an opportunity to harness the incredible talent in the Bay Area and combine that with smart approaches to technology and business. Since we’ve worked at shops both big and small, we’ve witnessed first hand the ideal size of a visual effects team, where morale is high, artists are creatively challenged, work gets done quickly and looks amazing. Those are the things we are passionate about.

For our employees, we strive to create the growth opportunities that only a start-up culture provides. It’s important to us that artists regard Atomic Fiction as a partner in pushing forward their career, as an opportunity to grow and innovate more quickly than they might elsewhere.

As far as lessons learned, one of the most frustrating aspects of working at a “big shop” is how ordinary tasks can become encumbered by pipeline and process. On the other hand, a “small shop” is often unable to roll with the punches, and can struggle to grow when a show gets out of hand. Our culture is to take aspects of a big shop pipeline (asset management, production tracking, etc.) and crossbreed that with small studio culture and values.

Combined this with cloud rendering, commercially available tools with custom “glue” and a get-it-done approach, and you have a winning combination.

How did Atomic Fiction get involved on this show?

I’ve been a huge fan of Rian Johnson’s work since BRICK, so when I learned about LOOPER, I reached out to see if there would be a fit. At the time, Karen Goulekas, the production visual effects supervisor, was pulling together companies to tackle various aspects of the show. Brian Flora, (our art director on LOOPER) and I met with Karen and discussed the best way to approach the digital environment work, first with a solid concept phase and later moving those shots toward final.

How was the collaboration with director Rian Johnson and Production VFX Supervisor Karen Goulekas?

It was a great collaboration that just worked from the beginning. Rian and Karen are fantastic to work with, and really made it easy for us to collaborate and contribute ideas throughout the process. Right off the bat, we were invited to watch a rough cut of the film so we could understand how our shots would fit into the overall picture, and form a solid understanding of the theme and tone of LOOPER. This was incredibly important and really laid the groundwork for all the creative decisions we’d make. As our concept art progressed, we worked closely to make sure Rian and Karen’s vision was integrated in our designs. They gave us the perfect amount of guidance and just enough space to let our team’s passion and creativity flourish.

What have you done on this show?

Atomic Fiction completed around 30 pieces of concept art and 72 final shots. Our work entailed everything from full-CG digital environments to set extensions and enhancements such as graffiti, building mods, futuristic traffic lights, etc. Other shots involved flying helicopters, drones, blimps and background vehicles.

What were your references for the futuristic cities and vehicles?

Rian really wanted his film to have a classic feel, so we took that as an opportunity to re-watch all our favorite films from growing up. I also wanted my team to find their own way in the look of the environments, so we established some new ground rules for the look of things. This included finding common elements such as graffiti, shelters/tents, antennas and campfires to tie our shots together and, more importantly, give LOOPER’s cityscapes their own signature feel.

How did you collaborate with the art department?

Principal photography was wrapped by the time we got involved, so that opportunity had passed. On the other hand, Karen had been working with a designer to establish some first-pass artwork on the buildings and vehicles. We were able to start from these designs and, more importantly, have a discussion with Karen and Rian about where they wanted to go next. It was a great jumping off point.

Can you tell us more about the city’s creation?

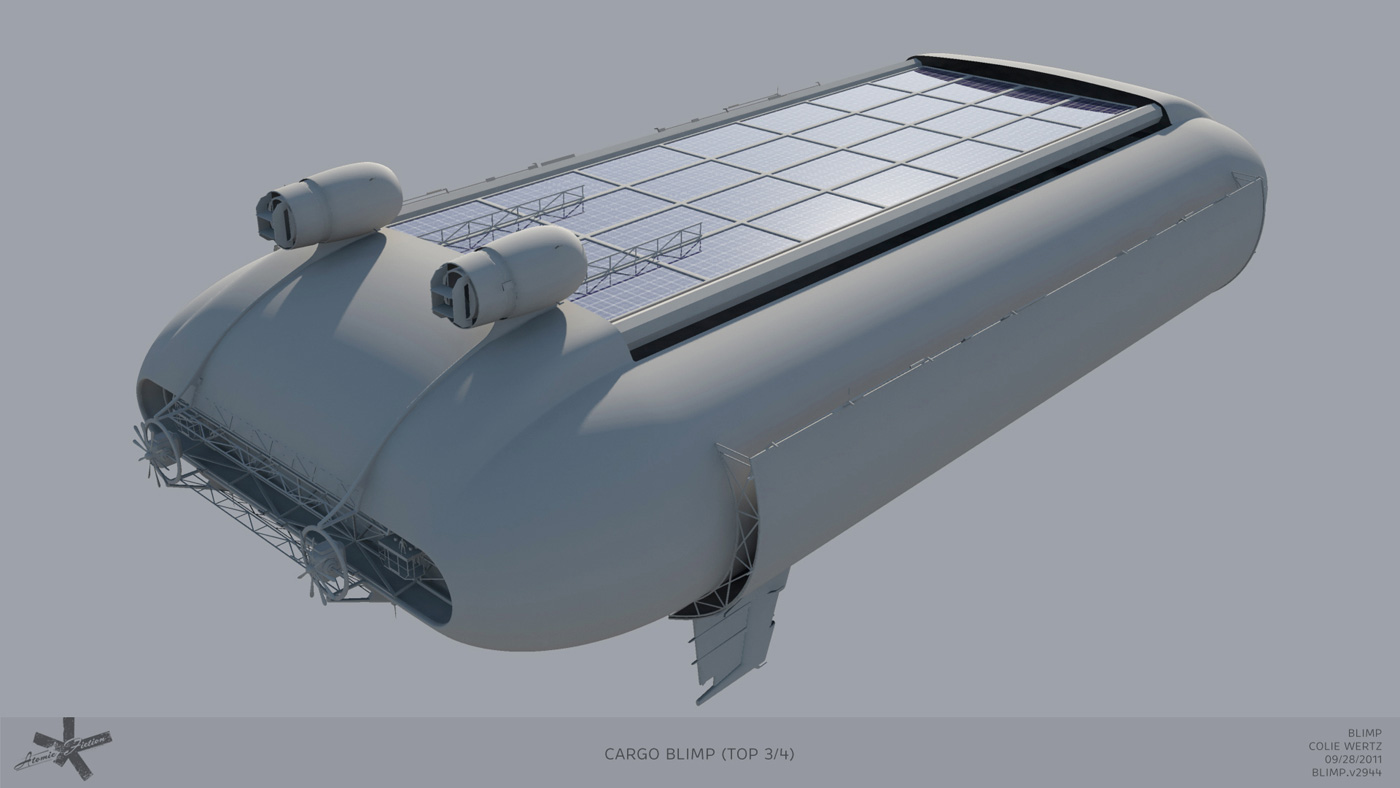

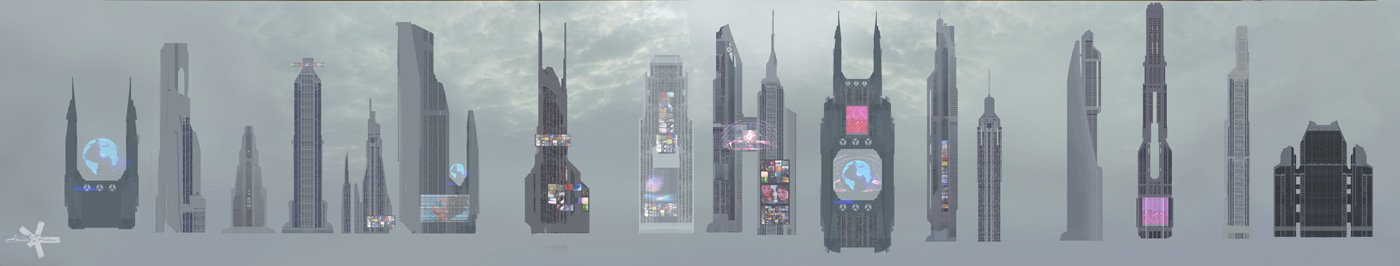

Our team consisted of several “idea” folks who really brought a lot to the table in terms the cityscapes. Brian Flora and another one of Atomic Fiction’s art directors, Chris Stoski, were both instrumental in defining the concepts and initial building designs. We all agreed the best place to start was to paint a dozen buildings all lined up, so we could begin to explore the silhouettes and how they might look against the sky. Once we had our buildings, the guys would tackle each shot as a single piece of concept art. Based on that artwork, our modeler Colie Wertz would build the hero buildings based on the camera’s viewpoint. He did a fantastic job taking the concepts and flushing out every detail. Those models would then go back to Chris and Brian, who by that time had switched gears into matte painting. They applied rough textures and lighting and went to work creating the final look as you’d expect, using 2D paint to add additional details and dial the mood / atmosphere.

What is your work methodology with the matte-paintings?

For modeling all the buildings and vehicles, animation and most lighting, Autodesk Maya is our primarily tool. We use Autodesk 3ds Max for matte painting projections and environment work in general. Our renderer is Chaos Group’s V-Ray. All of the painting itself is done in Adobe Photoshop and the final composites are done with The Foundry’s Nuke.

How did you manage the challenge of the tracking?

The tracking definitely got the better of us, and ended up taking quite a bit longer than we estimated it would. This was primarily due to extremely odd artifacts created by the anamorphic lenses. Lens distortion was extremely heavy at the edges of frame, but also inconsistent at the same time. The footage was dark and very grainy, which the software wasn’t too happy about either. At the end of the day, we just had to muscle many of the shots through by hand.

What the most difficult challenges with the futuristic cities shots?

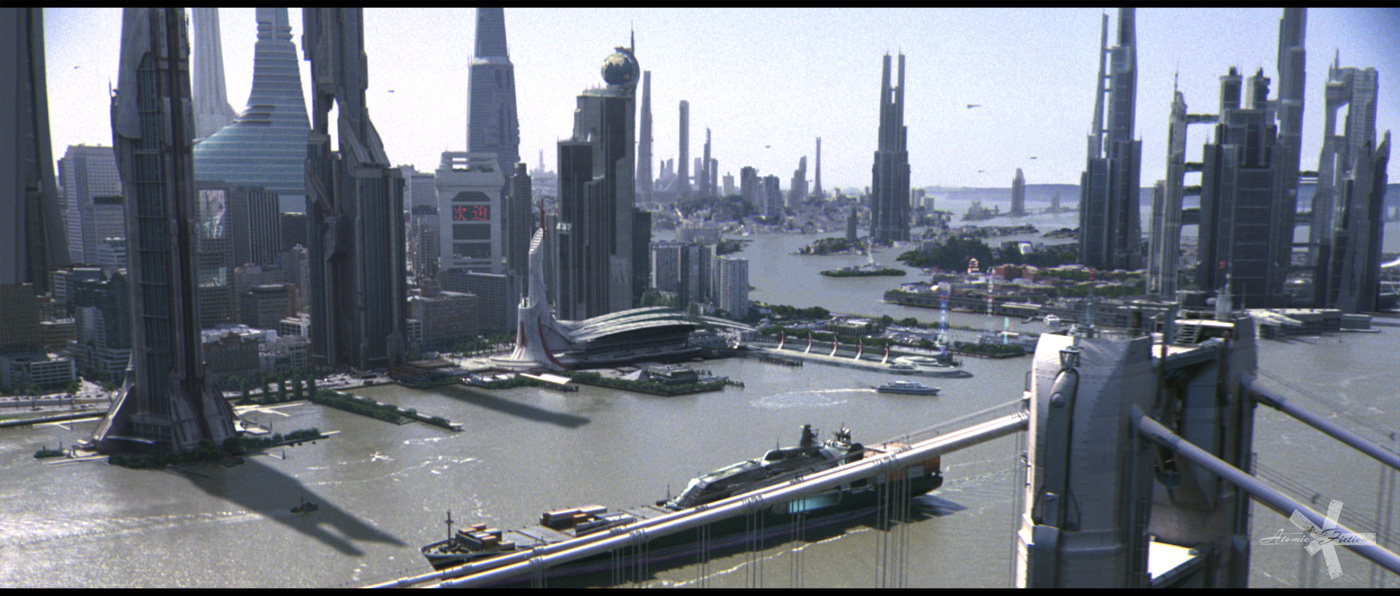

One of the things we struggled with from a creative standpoint was how much atmosphere to put into the shots. It actually became a funny joke between Karen and I. She was always giving me a hard time because our shots were too hazy! We happen to work across the bay from San Francisco, which is typically a foggy city. With this engrained in our mind, we were adding haze in an attempt to seat the buildings into the shot, give them scale and add more drama. In the end, the challenge was finding the right balance of atmosphere that worked with the filmmakers’ vision and fed our addiction to haze. I would have preferred much more haze, so in the end, Karen won.

The movie features also futuristic vehicles. Can you tell us more about their design and creation?

The vehicle designs were provided to us by the production as concepts, so we really just had to flush out the details. There were essentially three vehicles: a drone, a helicopter and a blimp. Of those, the blimp was the most fun, since the concept called for a massive balloon structure that carried hundreds of shipping containers on its belly. I don’t believe the blimp was ever featured in a shot to the degree we designed it out, but it was one of my favorites.

The great part was that we weren’t afraid to hide the vehicles behind crazy bright flares. This was homage to BLADE RUNNER, of course, but it’s also more accurate to how live-action photography of an aerial vehicle would look, especially with a bright searchlight pointed at the lens.

How did you manage the vehicles interactive lights?

I’ve always been a huge nerd when it comes to lens flares, especially anamorphic ones. It’s easy to get 80% of the way there with a plug-in, and actually quite complicated to create a system that matches all the beautiful, subtle details and movements of a real lens flare.

On LOOPER, we had great reference of course, since the film was shot on anamorphic 35mm. I challenged two of our lead artists, Jim Gibbs and Jesse Russell, to recreate every nuance of the live action flare, including the way the secondary flares pinched and warped, the color transition and distinct movement of the aperture stripe, the way dirt on the lens was lit up when the light hit the camera just right, everything. It took them a few days, but in the end, we were putting our CG lens flares right next to real ones, and nobody will ever know the difference. Jim and Jesse did a great job!

Can you tell us more about Joe escaping his apartment?

We tackled a handful of shots in this scene. In that section of the film, our work included mostly set extensions and the addition of flying vehicles such as drones or a blimp here or there. In one shot, we added a CG stunt double that fell from Joe’s apartment into the roof of a car.

Can you explain to us in detail the creation of the establishing shots of Shanghai?

The Shanghai shots were similar to other environments we created for LOOPER, except that we pushed the “future” aspects a bit further, with many more billboards and grander building designs. Shanghai, of course, represents the more prosperous setting, so we did our best to push these environments in ways that supported that aspect of the story.

One shot in particular involved a plate of San Francisco, in which we completely re-structured the layout of the city, added futuristic buildings, a port and modified both the Bay Bridge and a cargo ship in the harbor. It was fun working on a plate of San Francisco since it’s our hometown.

Can you tell us more about the cloud computing process?

The cloud allows our team to be more nimble and more effective than ever. We designed Atomic Fiction with the cloud in mind. When a facility builds a local render farm, they are required to build for peak capacity, which means the system is underutilized most of the time. Atomic Fiction, on the other hand, has been working with a company called ZYNC to utilize Amazon’s EC2 cloud. By moving rendering to the cloud instead of owning the computers, we treat rendering like a utility and only pay for what we use. This means that rendering can literally be scaled from as many cores as we need for a particular job, back down to the Macs on the artists’ desks. The benefits are numerous. When a job doubles in size, we aren’t limited by our ability to render the work, and artists get much faster turnaround. It’s a complete game changer.

In using the cloud, we’ve taken the issue of security very seriously, with high-end firewalls, a well-engineered internal network architecture, and heavy encryption of data going into and out of the cloud. Despite these intense security precautions, we are careful to only process individual elements of a shot, not entire scenes, with the cloud. Those micro-level components pose a much smaller security risk for our clients. We believe that the most important security measure of all is the professionalism of your staff and imparting to them how important the issue of security is.

If your readers are interested in learning more, we’ve posted an overview of our cloud efforts here.

Have you developed specific tools on this show?

As I mentioned, it’s part of our culture to rely on commercially available tools with custom “glue”. This allows us to only build what we need, and rely on the heavy lifting of companies such as Autodesk, Adobe and The Foundry.

That being said, we’re constantly iterating on our asset management tools, cloud-rendering plug-ins, color pipeline, MEL scripts, Python scripts, etc. Each show that comes through the studio pushes us forward in one way or another.

One of our most important internal tools is called “Fidget”, which is our asset management database, disk space monitoring tool, dailies system, plate ingesting tool, notes database and outsource vendor interface all rolled into one. The architecture was designed by our CG Supervisor, Mauchi Baiocchi, and is one of the critical “big shop” components I referred to. Atomic Fiction simply wouldn’t be able to do the volume of work that we do, on LOOPER and other shows, without this tool.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

In regard to the digital environments, our goal from the beginning was to play a supporting role to the characters and story. In that regard, the challenge was to find an understated elegance, which enhanced the story without drawing attention away.

Karen taught me a great technique when working on a film like this. As she looked at a shot, if her eye was ever drawn to our “effect”, it meant something was wrong; it was sticking out. When this happened, we’d work together on finding the solution, which usually entailed matching reference or backing off one way or another. For example, some of our initial concepts took the city designs in a direction that was too elaborate. We designed one building in particular with these super cool support beams, as if the building had been modified, but it was drawing the eye so we removed them.

We weren’t afraid to remove entire buildings because they weren’t fitting in, either. During the concept phase, we’d paint in silhouettes and convey rough design, which we all agreed was working. As the final shots came together, and we began to integrate some of these more elaborate designs, we realize they didn’t fit into the grander purpose of the visual effects.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

Oh, no. That wouldn’t be very fun, would it?

What do you keep from this experience?

I’m really proud of the work our team did, and incredibly thankful for the opportunity from Rian Johnson, Karen Goulekas and Ram Bergman. It’s especially rewarding to work on a genuinely good movie. It has been amazing to see the fan reaction to the film, which has very little to do with visual effects, of course, and far more to do with Rian’s amazing writing and directing. We’re just so pleased to be along for the ride!

How long have you worked on this film?

Atomic Fiction produced work for LOOPER across three distinct phases: Concept art (4-6 weeks), VFX shot production (4 months) and additional work for the Chinese release (2 months).

How many shots have you done?

72.

What was the size of your team?

Our crew on LOOPER was around 25, not including roto/paint support. It was a good size. We gained a lot of efficiencies from being small and nimble, and it allowed artists to handle multiple aspects of their shots. As I mentioned above, Atomic Fiction is all about crewing our shows with A-list people and giving them more responsibility. It’s amazing working on projects in this way, rather than strongly delineating between departments. It’s so much more rewarding for everyone.

What is your next project?

We’re ramping up on three major projects right now. I can’t talk about any of them yet, but we’re super excited and can’t wait to share more soon!

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

For visual effects, I’d say four different franchises: STAR WARS, INDIANA JONES, TERMINATOR and JURASSIC PARK.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Atomic Fiction: Official website of Atomic Fiction.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2012