In 2010, Paul Franklin had explained to us the Double Negative’s work on INCEPTION. Two years later, he reworked with Christopher Nolan on the conclusion of his BATMAN trilogy. He reteamed with the director this year for INTERSTELLAR.

How did you approach this fifth collaboration with director Christopher Nolan?

The great thing is that after working together for so long – more than ten years – we both have a pretty good understanding of each other; Chris knows that VFX will do its absolute best to achieve whatever challenge he sets us and I have a very good understanding of what is going to work for his film. All of the “getting to know you” part of the process is done with, so we can get right on with business.

Can you tell us more about your work with him?

Chris’s scripts are always very descriptive, but they don’t tell you how you should be doing things. He’ll tell you how he’d like to work – for example, build a real set so that he can shoot the actors on it – and then it’s up to you to work out how to do it. He is very collaborative and constantly pushes everyone to achieve more than they thought they might be able to at the start of the project.

How did you work with VFX Supervisor Andrew Lockley?

Andy and I have been working together for nearly fifteen years. We’ve worked together on really big shows as well as really small ones – our first show together had a total budget smaller than just one of the INTERSTELLAR Black Hole shots. Andy has a fantastic knowledge of compositing which compliments my background which is originally in 3D graphics. We’re from more-or-less the same part of the UK which helps as we can understand each other’s accents!

My other key collaborators in the VFX team were my producers Kevin Elam and Ann Podlozny, CG supervisors Eugenie von Tunzelmann and Dan Neal, 2D supervisor Julia Reinhardt Nendick, data wrangler Joe Wehmeyer, Dneg Chief Scientist Oliver James and – of course – scientific advisor and executive producer Professor Kip Thorne.

Can you describe one of your typical day on set and then during the post?

Whilst we’re shooting in the US my day starts at 5:00am with a cineSync with the team in London. I think it’s very important to give the guys continual feedback on their work and also to let them know how it’s going on set and what’ll be coming their way later on in post. We do as much work up front as we can as Chris likes us to move very quickly once he’s turned stuff over so it’s good to have as many of the assets and methodologies in place as is possible. Crew call is usually 7.00am, but most of the HODs are on set by 6:45am at the latest as Chris likes to get going on the dot of seven and be up and shooting by 8:00am. Most of my job is to observe what’s going on and advise when necessary, but INTERSTELLAR had the added demands of the on-set digital projection, which I ran with the VFX crew, and also the miniature shoot which ran in parallel with the end of principal photography. If I’ve got something to show Chris from the cineSync session then I’ll take it on set on my laptop and show him either between setups or at the end of lunch. Of course, I’m not the only one who wants to talk to the Director so I have to arrange a slot with Andy Thompson, Chris’s PA – there’s a structure to all of this!

After wrap I’ll get something to eat with the rest of the HODs and then we watch dailies – as is well known by most people, Chris likes to shoot on film and he generally prints everything he shoots. We project everything in a theatre or in a mobile projection trailer – there’s no digital dailies on Chris’s shows – and all of the HODs and leads are expected to attend. It can add a couple of hours onto an already long day, but the result is that I am fully acquainted with what Chris has got on film, what worked and what didn’t. This routine goes on for several months, and it’s fair to say that after 100 days of principal photography I’m pretty worn out!

During post my day is a little less arduous. I’m back in London where I live and where Dneg has its main studio and after I’ve helped my wife get our three kids to school I head into central London. We start at around 9am with VFX dailies at 10am. Dailies can run as short as 30 mins at the beginning of post, but by the end it can stretch out to several hours. After dailies I deal with specific shots, sometimes analysing them with the toolsets that we have at Dneg, and also working directly with specific artists. After lunch we have a second dailies session. In both sessions we’re selecting material that we want to put in front of Chris who likes to have a daily VFX review with me. We send stuff over to LA, where Chris lives, on a secure upload and then Chris starts his day at 8:30am (4:30pm in London) in VFX editorial where we use cineSync to go through the work. The time difference really does work in our favour for the most part as we’re able to prep things whilst LA is sleeping. The colour guys at Dneg work hard to ensure that the cineSync stations in LA and London are showing exactly the same thing and the interactivity of the system makes it a real winner for us. Steve Miller, our VFX editor, has been part of the team since THE DARK KNIGHT and he stays on top of everything, no matter how fast and crazy it gets. Once Chris has viewed the work and given feedback it all goes straight to main editorial and gets dropped into the cut. Lee Smith – our editor – has been part of the Nolan team since BATMAN BEGINS so if he has any specific questions or if there are any things that need urgent work he’ll call me directly. Again, the familiarity with everyone in the team makes it very easy to get on with work – it’s a very tight unit.

As post progresses I fly over to LA to view screenings of the film and to work on specific things directly with Chris. We also continued to shoot miniatures well into post so I think I was in LA almost as much as I had been during production. By the end of the show the airline crews knew me pretty well by sight!

The hero catches an Indian drone. Can you tell us more about it?

For the most part the drone in the movie is practical – Scott Fisher’s SFX department worked with a team of radio controlled aircraft specialists who built a 1/3 scale flying model of the full-size drone – it looked amazing swooping over the big cornfield and through the Alberta skies. We added a digital drone to a handful of shots where it just wasn’t possible to get the radio controlled version into the shot – mostly the angles looking up through the windshield of Cooper’s pickup truck.

How did you created the various sandstorms?

We did three digital dust storm shots – two in the baseball game scene and one other scene set many years later. The rest of the dust storms were created practically by Scott Fisher’s team using a special non-toxic cellulose dust and huge wind machines. The digital work required a lot of research, looking at real dust storms in the deserts of Africa and also at archive material of the mid west dustbowl of the 1930s in America. The team at Double Negative used a combination of Houdini and proprietary tools to create the huge towering clouds that slowly advance on the baseball stadium. There was no green screen so the rotoscope artists had a lot of very meticulous painstaking work to do as all the dust shots were full IMAX.

How did you approach the space sequences?

We wanted the space shots to look as authentic as possible, grounding them in the look and feel of the material shot by the astronauts on the International Space Station and also the images of the Apollo Lunar missions of the sixties and seventies. It was important to us that we maintained authentic exposure ratios so that fill light was only present if we were near to a planet or that the stars would be invisible if we were exposing for direct sunlight on the space craft. The camera work was also informed by archive footage – we avoided floating cameras, instead we always tried to find a position on the spacecraft themselves, hard mounting to the hull or some part of the superstructure. The only time we broke that rule was with a handful of super-wide shots where we see the spacecraft as tiny motes crossing the face of a planet, wormhole or black hole.

Can you tell us more about the spaceships and the station creation?

We had two smaller vehicles, the sleek shuttle-like Ranger and the heavy duty Lander, and one mother ship, the big wheel-shaped Endurance to which the smaller ships attach. The original plan was to do the straight space travel shots digitally and use miniatures primarily for close-ups and destruction moments, but once we started seeing how good the miniatures looked on film we shifted to using them for most of the shots, with digital comprising less than ten percent of the final space ship shot count.

Cooper Station was a digital creation, utilising matte paintings created from aerial IMAX plates of the Alberta farmlands which were put onto a cylinder. The cylinder was then used to extend the location plates of shot in Canada – lots and lots of detailed rotoscoping and first class compositing went into integrating everything.

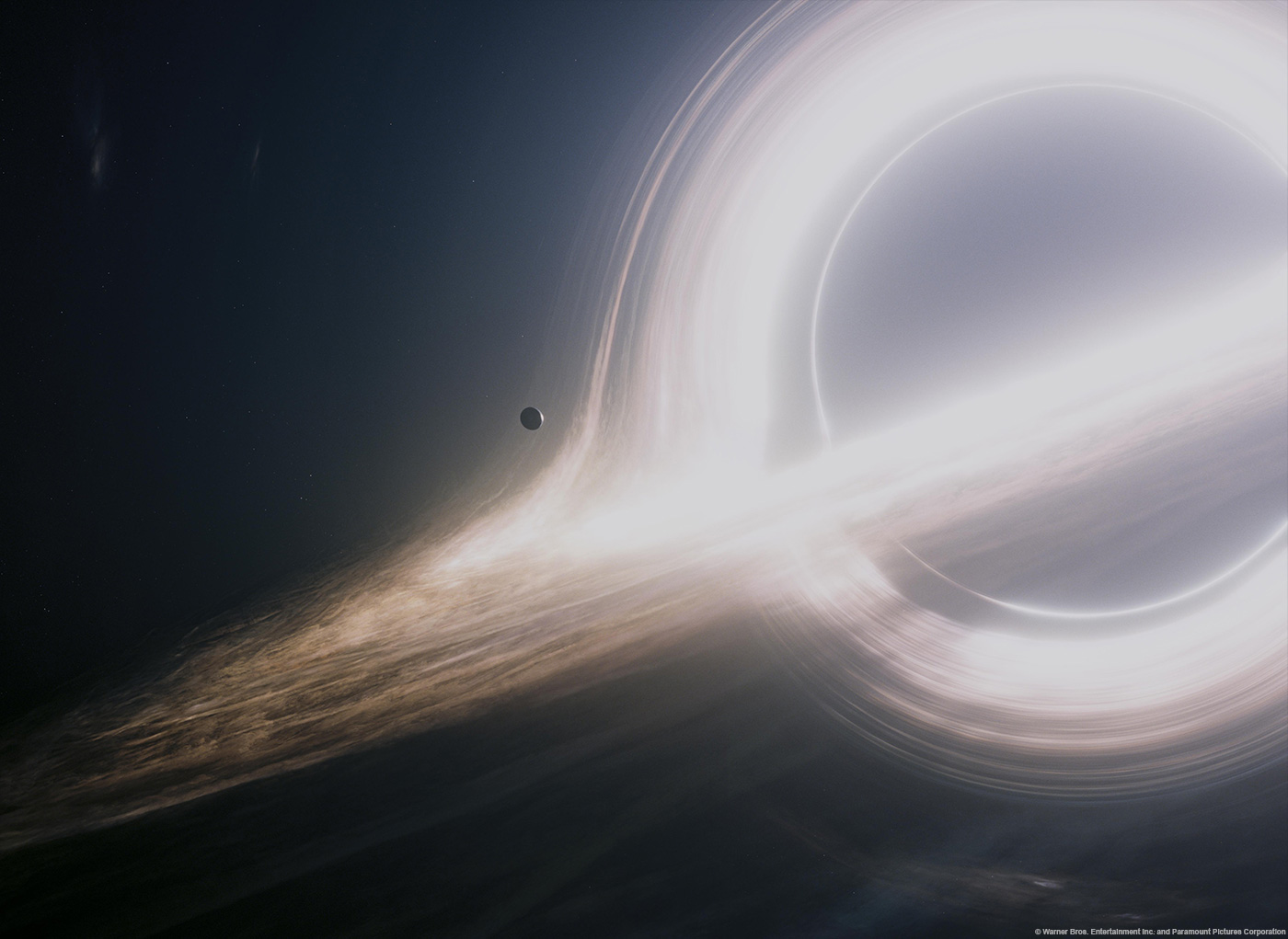

The movie features the black hole Gargantua. How did you find its beautiful design?

We spent a lot of time thinking about how we were going to show the power and majesty of the black hole. One of the big problems is that a black hole is, well, black! It has no surface features, no highlights, no low lights, just black. But then I read about the accretion discs that often form around black holes – huge whirling discs of gas and dust that are sucked in by the black hole’s immense gravity. As the material gets closer to the hole it heats up with friction, releasing vast amounts of energy and shining brilliantly. We realised that we might be able to use this to define the shape of the sphere of the black hole. But I was keen that we not just draw a picture and use that for our black hole – fortunately we were blessed with the best scientific advisor that we could have asked for in the person of Professor Kip Thorne. Kip developed equations that we then implemented in a new renderer to trace the light ray paths around the black hole. The result was a stunning image that accurately depicted the shape and characteristics of the black hole. When I saw the early images coming out of the software that the Dneg R&D team had produced I realised that we didn’t need to dress it up in the way that science fiction films often do – the science alone gave us a compelling vision of this primal force of the universe.

How did you created the effects when they go through the worm hole and then the black hole?

For the worm hole we once again turned to Kip Thorne for help. He gave us reams of notes and equations that the Dneg R&D team, under the leadership of Chief Scientist Oliver James, implemented in a proprietary renderer. The renderer correctly depicted the lensing of the background universe produced by warped space around the worm hole. It also gave us the “fish eye” view of the distant galaxy that’s at the other end of the worm hole. Once the Endurance entered the worm hole we created the interior through ray-tracing of the wormhole’s interior environment (again driven by Kip’s physics) which was then combined with a dynamic rushing landscape derived from aerial plates that I shot in Iceland. The interior is more impressionistic than scientifically accurate, but we found that the images produced purely by the physics were so far out that they were just a bit too hard to understand!

For Cooper’s trip into the black hole we asked Kip what he thought might be beyond the event horizon – the point beyond which even light cannot escape the black hole’s gravity. Kip replied honestly that the interior of the black hole was relatively “unexplored” by science, but he gave us a few ideas about waves of in-falling space-time and back-scattered radiation which might result in a crescendo of light as the ship travels deeper into the hole. We interpreted this through largely practical means, shooting all sorts of special effects passes with our 1/5 scale Ranger miniature which was about 12 feet long. We mounted the miniature vertically on the ground with its nose pointing up. Directly above the miniature we had a one hundred foot crane from which we dropped a variety of objects and materials – the waves of scintillating particles you see in that sequence aren’t CG, it’s common table salt, hundreds of pounds of it. We were shooting in the open air in New Deal’s parking lot and the natural air currents produced beautiful waves and ripples in the salt streams – the back light made it sparkle as it fell – we didn’t have to do much to it to make it look great in the final comp!

The heroes are accompanied with the TARS. Can you tell us more about his creation and animation?

Chris wanted Tars – and Case, the other robot – to not look in any way anthropomorphic, to not just be a metal human or human analogue. After all, present day robots rarely look like people, just think of the machines used in car plants. The inspiration for the shape of the robots came from modern art, in particular the minimalist sculpture of the post-war period. Chris then explained his concept for the robots’ articulation: a series of three pivots on each of the robots’ four elements (or fingers, if you will) that could be switched on and off to allow the machines to configure themselves in a variety of ways. In addition, each of the four elements would subdivide into another four elements and those into another four elements, resulting in fine appendages that could be used for delicate manipulation. The principle was quite straight forwards, but the actual movement of the machines was very complex. Double Negative’s animators, lead by David Lowry, spent several weeks testing all sorts of possible movements for the robots. Meanwhile, physical performer Bill Irwin worked with Scott Fisher’s SFX team to build a practical version of Tars which Bill was able to puppeteer in a manner similar to a bunraku rod-puppet, but in this case one that weighed over 200 pounds. The final result that you see on screen is largely practical – over 80% of the final shots of the robots were achieved in camera with minimal digital work required to remove the performers from the shot. The remaining 20% were digital, especially the shots of the robots moving in free fall and the sequence with Case water-wheeling through the waves to save Brand.

There are various environments in the movie. How did you approach the waves and the icy planet?

As always, Chris was determined to get as much as possible in camera. We travelled to Iceland which provided us with the locations that became the basis for Miller’s watery planet and Mann’s ice world. Hoyte van Hoytema’s cinematography was the starting point for everything that we did, setting the tone for these sequences.

How did you created the impressive huge waves?

Chris told me that he wanted a mountain of water, a wave 4’000 feet high, something so huge that you wonder how the crew can possibly survive it. We looked a footage of big waves in the Pacific off the coast of Hawaii and took as much as we could from them, but in the end we had to use our imagination because the INTERSTELLAR wave was so much bigger than anything on Earth that a lot what we associate with waves – breakers, spray, white water – just didn’t apply in the same way. We ended up using a system of deformers that the animators used to move the large mass of the wave around. Once we were happy with the shape and overall dynamism of the shot we then ran detailed surface simulations using Dneg’s proprietary Squirt Ocean toolset to give us all the small wavelets. On top of that we ran simulations to create the surface foam and spray. It was very laborious so we had to be pretty sure that we had the overall composition right before heading into the simulation work which took weeks for the hero shots of the Ranger riding the wave. One trick we used to sell the wave’s immense scale was to have it rise up against a background plate and then hold out the clouds so that the wave was behind them – this really showed us just how enormous the wave was meant to be.

Can you explain in details about the icy planet environment?

The glaciers of southern Iceland gave us the basis of the environment. We made digital matte paintings – built largely from photographic reference of the glaciers themselves – and used them to replace the background mountains and anything else that wasn’t made of ice or snow. For some shots we carved holes into the glacier plates and added vaulting ceilings of ice, suggesting a complex layered environment with no defined rocky surface. The actual Icelandic glacier had a lot of dirt woven into the ice, giving it a striking marbled look. We incorporated this into the extensions and even added a very subtle dirt treatment to the cloudscapes that we shot using an IMAX camera nose mounted onto a modified Learjet.

The hero arrives in a special version of his girl library. How did you design this sequence?

When Cooper descends into the black hole he finds himself in a mysterious environment consisting of multiple versions of his daughter’s childhood bedroom back on Earth. The rooms are embedded in an endless lattice of intersecting lines, extruded from the rooms themselves. It becomes apparent that the multiple rooms are actually instances of the same room at many points across time, the linking structure representing the extruded timelines of all the objects within the rooms. Cooper is unable to enter any of the rooms but he finds that he can manipulate the timelines, indirectly affecting the interiors of the rooms. We christened this environment “the Tesseract”, referencing the mathematical concept of a four dimensional “hypercube” – the key to this environment is that it presents time as a physical dimension, allowing Cooper to navigate its structure to find key moments in the history of the room and interact with them. Conceptual design of the Tesseract started at the very beginning of preproduction and we did a lot of research into various ways that time had been represented in art and photography. One area of particular interest was slit-scan photography, a technique almost as old as photography itself. Unlike a regular photograph, which captures one moment in time across many locations in space, a slit-scan image captures one location in space across a period of time, recording everything that happened in that space over the duration of the exposure. One of the earliest applications of slit-scan was in the finishing line photographs taken at horse racing tracks which often show distorted – but recognisable images – of the horses crossing the line but which render all static objects as horizontal streaks or stripes. The Tesseract was a three-dimensional extension of this idea, with all the objects in Murph’s bedroom being extruded out into solid timelines extending beyond the limits of the room. The extrusions on one axis intersect with extrusions on the other axes with the instances of the bedroom being revealed at the intersections. Within the rooms themselves we carry on this idea in the form of faint, gossamer-like timeline “threads” that track with all the objects – and all the people – in the room.

Can you tell us more about its creation?

The Tesseract was perhaps the most complicated digital environment to construct and started with a survey and scan of the original bedroom built inside the farmhouse set in Canada. Each object in the room was recorded in high resolution and a detailed digital model of the bedroom was reconstructed. From this we then generated the extruded timelines and the fine mesh of threads. Each instance of the room contained a full set of furniture and objects which made the scene extremely heavy – the Dneg 3D team came up with a number of clever ways of dealing with the geometry load and devised a strategy for rendering that made use of Houdini’s Mantra renderer.

At the same time Art Department were building a physical version of the set that we would use for principal photography. Double Negative and Art Dept. shared the digital models as they developed which in turn informed the physical build. Working from the digital extruded timeline models Art Dept. built practical physical versions which were incorporated into the set. Dneg’s on-set survey team kept track of the physical set’s construction, sending through updates to ensure that the London team had an accurate record of how the physical set was developing.

Matthew McConaughey was suspended on a wire rig within the physical set to simulate zero gravity – all shots within the Tesseract sequence were filmed with IMAX cameras to give us the biggest possible canvas to play with. Animating patterns of traveling light were projected directly onto the set with powerful digital projectors – at one point we had over a dozen projectors running simultaneously to create a sense of constant motion over the imposing geometric structure of the set.

The physical set was extended into infinity with the digital model and additional layers of animation were layered over the physical set. Within the rooms the fine mesh of threads linked to every object, careful match moving allowed the threads to track with the actors as they moved around within the set. For the distant views of the repeating rooms digital doubles of Mackenzie Foy and Matthew McConaughey repeated their action into the distance.

How did you created the huge environment of the Copper station?

Cooper Station was imagined as a “canister world” that spins along its long axis to create gravity. We shot the exteriors on location in Canada and then made matte paintings from aerial IMAX plates of the Alberta farmlands which were mapped onto a cylinder. The end cap of Cooper Station was modelled in 3D and incorporated structures based on architectural research carried out in London and the USA. Careful attention was paid to matching the sun position in the location plates, using it to drive the lens flares seen in the complex array of mirrors in the end cap. Integration of the CG environment was achieved through meticulous rotoscope work and skill full compositing.

Can you explain in details about your collaboration with New Deal Studios?

New Deal Studios have provided miniatures and models for Chris Nolan’s films starting with THE DARK KNIGHT in 2008. My own relationship with New Deal goes all the way back to PITCH BLACK in 1998. They always do a fantastic job, creating amazing models and then shooting fantastic material that sits in perfectly with the rest of the film’s photography. INTERSTELLAR was no exception to the rule and Ian Hunter’s team created a range of beautiful models that included a 1:1/15 scale model of the Endurance that held up to the closest level of scrutiny – my original plan had been to use the miniatures for just one portion of the space shots, but when we saw the footage it looked so good that we ended up doing almost all of the space shots as models. New Deal also shot the fantastic special effects sequences that we used to create Cooper’s journey into the Black Hole.

What was the main challenge on this show and how did you achieve it?

The biggest challenge was just to get my head around some of the more abstract aspects of the story and work out how to bring to them the level of gritty reality that we needed for the film. In a way it’s easier to do something like INCEPTION, where the majority of the concepts were grounded in our real world, even when we were being quite surreal. For INTERSTELLAR we wanted to show the audience things that no one has ever seen before – warped space time, black holes, interstellar travel – with the same level of documentary realism that we try to bring to everything we do for Chris Nolan’s movies. Fortunately, I was working with the most amazing collaborators that I could hope for in both the production and back at Double Negative in London.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

There were a number of high stakes sequences: the worm hole, the black hole, the ice planet, the water planet and – of course – the Tesseract, all of these involved huge amounts of work and vast amounts of machine time, and all of them had the potential to go spectacularly wrong, but the team delivered amazing results, time after time.

What do you keep from this experience?

That there really are no limits to what can be created visually.

How long have you worked on this film?

I was working on the film for around 18 months.

How many shots have you done?

The finished movie has around 700 VFX shots in it of which 600+ were in IMAX at 5.6K. The rest of the shots were 4K anamorphic. As with all the other films that I’ve done with Chris Nolan, everything was finished photochemically on film without a digital intermediate process.

What was the size of your team?

Around 450 people worked on the VFX of INTERSTELLAR.

What is your next project?

Taking a holiday!

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Double Negative: Dedicated page about INTERSTELLAR on Double Negative website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2015