Last year, Adam Valdez speaks to us about the effects of MPC for THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA: THE VOYAGE OF THE DAWN TREADER. This time, he explains his work on JOHN CARTER.

How did MPC got involved on this show?

We were asked to come in midway through post, to help finish a scene that needed a boost. Typically this is called “911” work, but in this case the decision was made in good time and that meant we had a nice schedule to work on what turned out to be some tricky work.

How was the collaboration with director Andrew Stanton?

Andrew is one of those guys who is genuinely making movies for his love of movies as an audience member, and his love of the process as a film-maker. For someone who is so involved in the day to day of animated films, I was curious if he would be a micro-manager, but on the contrary I found him to be very trusting and collaborative. I think he is used to the reality that a film by nature is the product of all the people who work on it. Some film-makers fight that, others manage it, and that’s what Andrew does. He will give you space to bring ideas, and will riff on your ideas if they are good, but is not shy about sticking to his vision when he is confident about it. One of my responsibilities is creating a rhythm to how we review work – that large enough pieces of the film are reviewed in time intervals which maintain creative momentum. A group of people, no matter how experienced, will lose momentum, even forget what we were trying to achieve, if we don’t see work progressing regularly. Andrew responded really well to this, and it allowed us to keep tuning shots all along the way to final, which he also appreciated. Andrew has an intensity about him but is always respectful and puts the movie first, not politics or ego. I have a lot of respect for that, and so it was a satisfying and fun experience to work with Andrew, DOP Dan Mindel, VFX consultant Eric Brevig, editor Eric Zumbrunnen, and producers Lindsey Collins and Jim Morris. The whole team were a genuine pleasure.

What have you done on this movie?

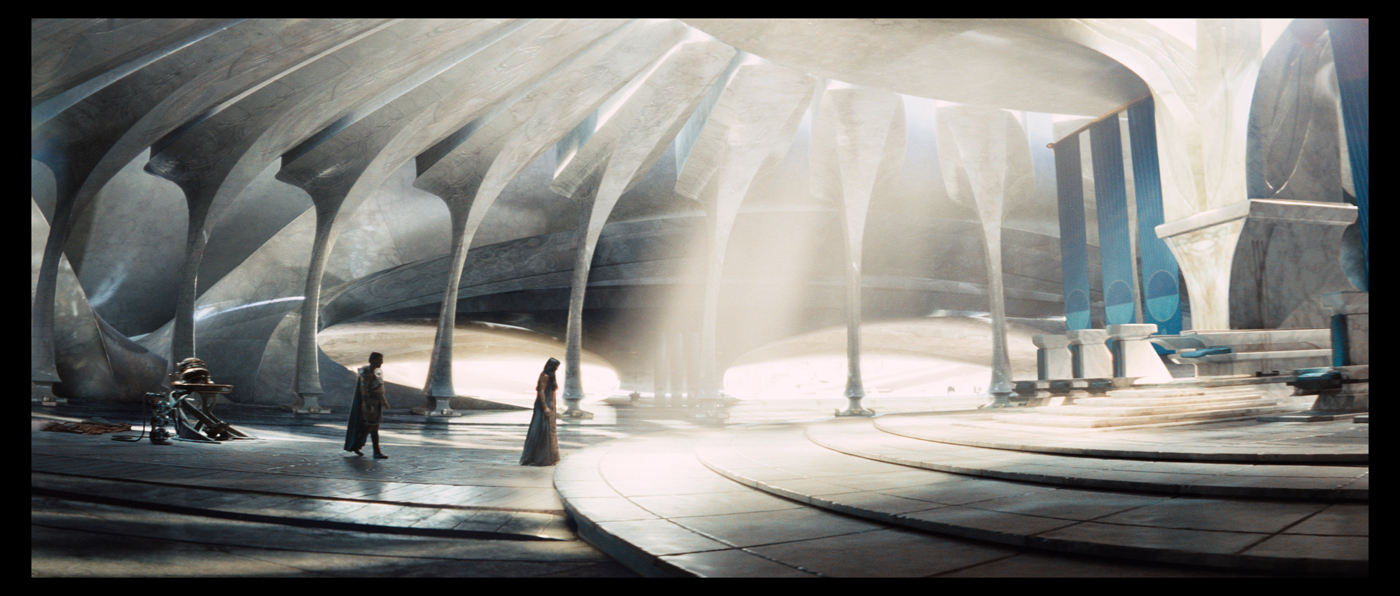

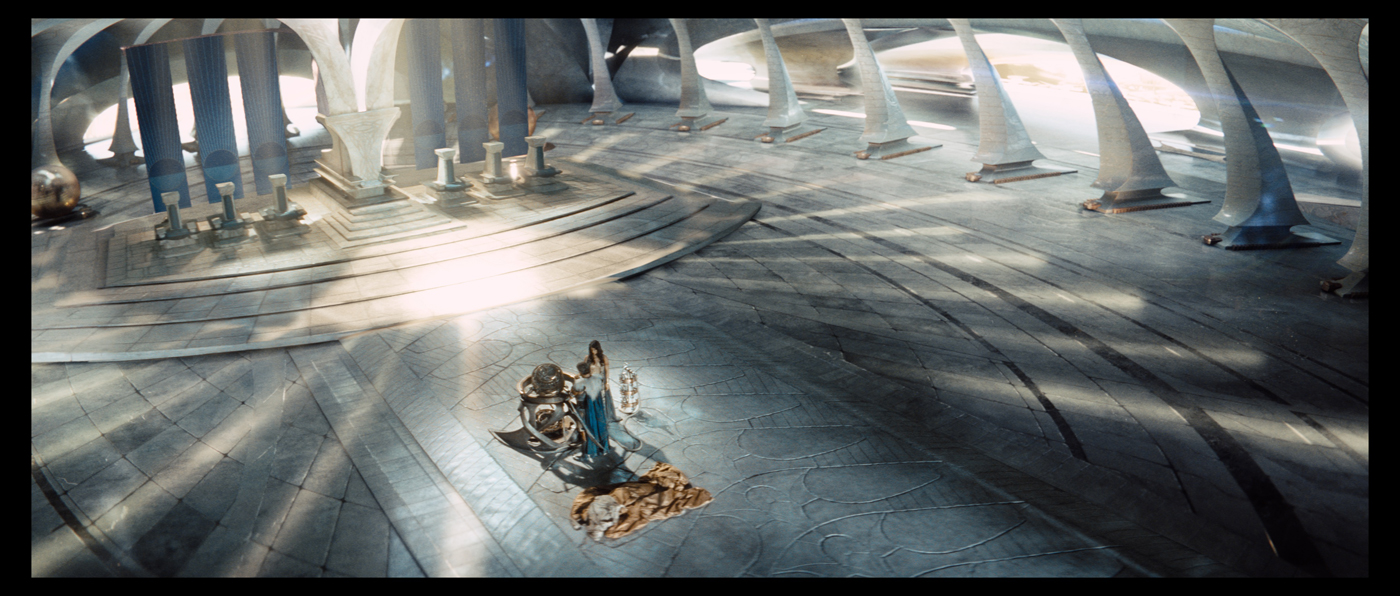

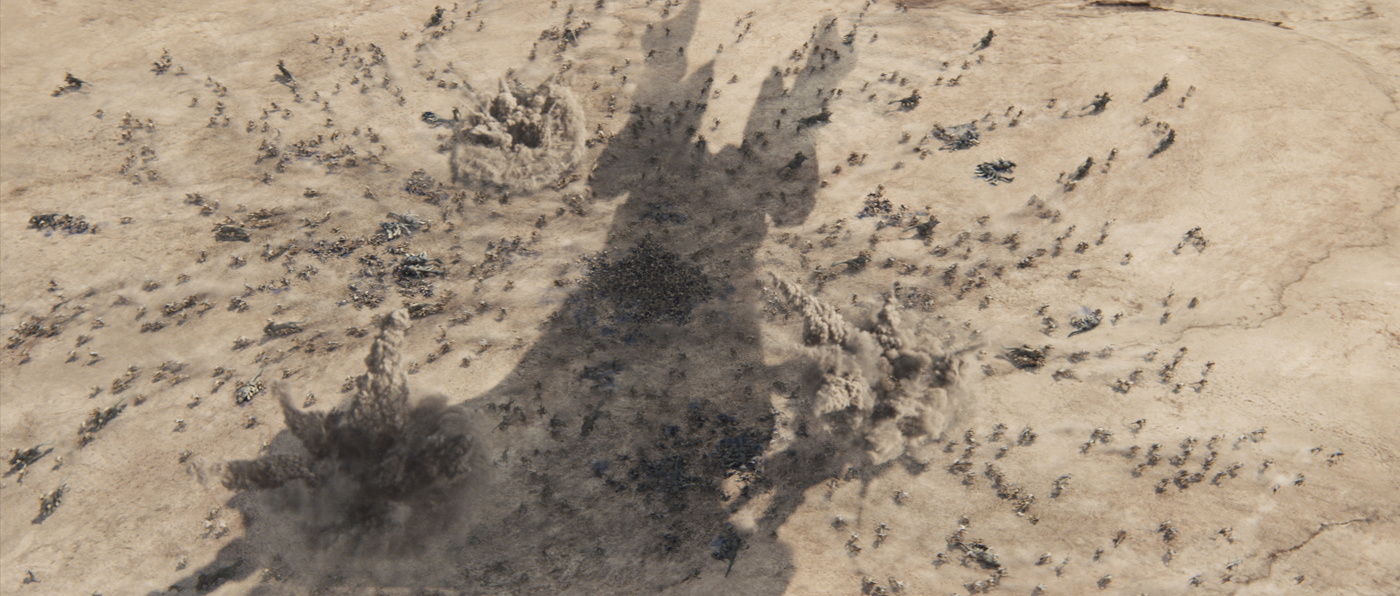

Our first big scene was the “Warhoon Attack” – when a couple thousand warrior aliens attack the heroes on the plains of Barsoom. Second was “Dejah’s speech” – a scene held in the throne room of Helium City, where a pivotal political decision is made by the King, or Jeddak, of Helium.

What was the real size of the set for the big hall in Helium?

The throne room set was rather big, but about 80% green screen. Dan Mindel lit for atmosphere and mood, and we later had to create extensions for the floor, walls and ceiling of this enormous room and the antechambers beyond it. The design came from Ryan Church, including a basic maya model which we imported and rebuilt. We presented a few design modifications to Andrew which helped improve composition for the actual camera angles, and from there it was all about getting the right mood and feel for this room. It was harder than I thought it would be. I hadn’t done a lot of architectural work in my career – and I knew we all wanted a fairly naturalistic look to the light bounce and sheen off the stone/marble material Andrew was after. But like many virtual sets, a further constraint is the live action footage. So the trick was bringing subtle 2d manipulations of the foreground characters toward the lighting of the room – for instance reducing certain colors from their hair and armor. Then, we used mental ray renders to produce bounce for the room, and combined this with renderman renders for texture and displacement. The compositors then took all of this and created the final look with several weeks of delicate re-balancing of shader outputs. It was an angle-by-angle thing, trying to create a certain beauty to the room without it becoming too stylized. This room was supposed to both evoke a respect of Helium’s artistic and technical prowess, while hinting that the city was very very old, and a bit worn. Ultimately when you have a beautifully lit face like the princess Dejah filling your frame, the total look has to frame around that subject. The room shouldn’t upstage her. Yet the room was a presence in the scene – a context. Finding that balance was tricky, but i think it comes across quite well in the end.

Can you tell us in details the creation of the Warhoon?

The Warhoons were originally modelled and textured at Double Negative, here in London. When we came on to help, they delivered all of that hard work to us, and we went through a few steps to get it all into our tools and pipeline. We did modify textures quite a bit as we commenced look development. This was the normal kind of stuff – increasing variation, rebalancing some of the weathering and distress to their skin and clothing. Andrew had a strong opinion that this kind of stuff needs to be fairly heavy handed to show up in the final film. That is, variation and detail which looks great in a slow moving turntable, often blurs out or is simply not seen when the characters are animated. So we made sure to increase the amount of mud and sun-bleached skin so there was greater contrast on their skin. We also boosted displacement maps to create more texture, crust and wrinkle to their skin. The chief Warhoon got special treatment, as he was featured in a few closeups.

Rigging these creatures was more straight forward than I expected. I thought the extra limbs would cause trouble. The riggers at Dneg had us over to discuss how they had solved some of these issues, and Dneg animation director Eamonn Butler was very generous with his time, getting us up to speed. Our rigging team worked out the idiosyncrasies of extra limbs quickly, and created puppets for the animation team, using a now very established set of tools, giving the animators a familiar set of controls. The crowd department, using our own Alice simulation and motion synthesis framework, had already worked out “horse and rider” workflows, and so having Warhoons which ride on “Thoats” – 6 legged running creatures, worked out really well.

An important part of rigging was dynamics for muscle, leather straps, and cloth. The Warhoons wear elaborate costumes which needed to behave under extreme battle conditions! Our riggers and cloth TDs did a lot of work in shots to tame this stuff.

What were your references for their animation?

Andrew kept prodding us to make the Warhoons more and more amped up. The Warhoons are kind of like day players – they arrive in the movie, and we don’t see them again. So they needed to make an impression quickly. The horde of Warhoons was in some shots as much impressionistic texture as animation. There is an ape-like quality to them, but you wouldn’t want the audience thinking of them that way – so we had to be careful we didn’t add too much shaking and stamping and hooting. The animators did film themselves doing certain moves, and we did use motion capture to create some clips to work from. But 95% of the scenes are built on keyframed work. Cycles were made for the Alice crowd system, and many of the big fighting shots were fully delivered by animators.

John Carter confronts the Warhoon army in an impressive fight. How did you choreograph it?

Andrew and Eric’s cut was already a strongly designed pattern. There was a piece of music providing a cut rhythm, and the fight was always planned to be inter-cut with a flashback scene. This scene was very dire, as John Carter discovers and buries his dead family. Carter’s emotion is what ties the scenes together – a desperation which drives him through the battle. So the basic design, screen direction, and screen-space flow of each shot had been story boarded over the background plates, and we started laying out the shots in our layout department to those boards. Almost all of the choreography was locked in at this stage. Of course it was tuned as we went, but our layout guys added lots of detail and specific action to each shot, so that Andrew knew it would work. As usual this process included many occasions where the drawn boards wouldn’t work, once the realities of actual camera lens and “stage space” in the maya scenes. This is where layout shines – working through these issues, adding creative ideas, and helping lock down a cut so the other departments at MPC can spend their time most effectively. When animation and crowd got into the scene, we had a great base, and shot by shot we referred back to layout, and changed as necessary, to make sure the audience’s eye could follow the flow of this fast, intercutting action.

Can you tell us more about the use of Alice for this fight?

Alice was used all over the fight scene. From shots of the Warhoons running across the desert, to the biggest fight shots, and ultimately when the Xavarian airship barrages the Warhoons with cannon fire. Dynamics are built into Alice, and came in handy as Andrew wanted lots of crashing and mayhem in the crowds. The crowd TDs added dynamics in-shot, on top of the blended animation cycles, to create a more integrated physical feel to the choreography. The crowd team has become very good at developing shots within a simulation tool. In fact the tools have been designed to give them lots of creative control – which ends up being better than full-on simulation by a brain network or games style engine. The TDs can build up work, share choreography, or modify choreography based on specific direction. It’s not easy! But ultimately it allows for naturalism, choreography, and the ability for animators to add any detail in a final step.

How did you collaborates with the other vendors?

We worked with both Dneg and Cinesite on this show – sharing shots and assets with both. We did some airship blocking for the Cinesite shots, which they then polished in their animation team, and sent back to us for the final lineup of the cannon fire raining down on the Warhoons. Quite a few shots overlapped with Dneg, wherein we had to choreograph scene terrain and composition. We do this more and more. It can be quite painful technically, but our relationships with other facilities is very good, and many of us are friends, so it always works out well.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

No. I never worried we wouldn’t make it on this show. Every show is a challenge for one reason or another. Here it was ramping up on a show, trying to participate with a group who had already gone through the shoot and other learning experiences together. When you miss that, you miss out on what was tried and ruled out – so sometimes you make mis-steps. We had a couple of those, but nothing big. I’d say the throne room was my biggest personal challenge – expanding my understanding of architectural rendering to achieve it.

What do you keep from this experience?

The take away for me is that when we provide a good working rhythm for a director, they will give us the most useful notes, and will feel confident we are working with them.

How long have you worked on this film?

I think we were on the project for about 9 months all together.

How many shots have you done?

180 shots.

What was the size of your team?

160 globally.

What is your next project?

I’m currently the VFX supervisor at MPC for WORLD WAR Z.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– MPC: Dedicated page about JOHN CARTER on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2012