In 2018, Jerome Chen explained the visual effects work on Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle. He later oversaw the effects for Men in Black: International.

How did you get involved on this film?

Director Jake Kasdan and I worked together on Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle and were regularly in touch after that. In September 2021 Dwayne Johnson and Hiram Garcia pitched Jake an original story idea for a Christmas action-comedy, and I became involved shortly thereafter. I was excited by the project because it was ambitious in scope, with a multitude of mythical creatures and environments.

How was this new collaboration with Director Jake Kasdan?

Jake is one of my favorites, I love working with him. He is a thoughtful, intuitive filmmaker with a keen sense for comedy. His process was extremely collaborative, always willing to listen to ideas but clear about why something would or would not work relative to his vision. He loves the details about visual effects work, and during post was highly involved in reviews.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Cari Thomas and I worked together on The Amazing Spider-Man 1, so we were in sync on how to work together. She is a veteran producer, so I was basically hands-off on the shot breakdown and budgeting process until she needed my input on specific issues. In terms of vendor assignment, load balancing is key so we can avoid a single point of failure during the final death throes of delivery.

Ideally, two or three anchor facilities are churning out shots at the same time across a broad swath of the film. With this in mind, Cari and I first broke apart the scope of work in terms of CG characters and then by digital environments, and though we at first tried to avoid duplicate assets at facilities, this would have placed too much at one facility – in this case, Rodeo FX.

Specifically, we assigned the first two action sequences to Rodeo FX, which required assets such as Nick’s sleigh, his reindeer, and a large portion of the North Pole City. The 3rd act also involved these same assets, which we ultimately assigned to Imageworks so we could have a single facility focus on the finale – which is often the section that is most in flux and the last to deliver.

How did you choose the various vendors and split the work amongst them?

I’m a long-time collaborator with Imageworks, and Chris Waegner (VFX SPI Supervisor) and I have worked on probably 10 films together over the last 25 years, so the shorthand there is powerful shorthand between us. My instinct was to place the 3rd act there, and the Snowman sequence – with Imageworks’ world-class animators – helped to balance their workload.

I had solid experiences with Rodeo FX on Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle and Men in Black: International, and they had a strong interest in working with Jake and I. They were key contributors, developing Garcia, the Polar Bear ELF agent, and accomplishing the vast North Pole City. Led by Julien Hery and Laurent Taillefer, Rodeo’s team also created the Sleigh take off from the military base, the first act Sno-Cat chase sequence through the City.

Cari Thomas’ positive experiences with RISE on previous projects led us to utilize them for some key scenes involving scenes of mostly supernatural nature, including the possession of a villain, augmenting the environment of Krampus’ foreboding realm, plus creature work involving Hell Hounds and a heroic chicken named Ellen.

What is your role on set and how do you work with other departments?

My job role adapts to each phase of the film project, of which there are basically three: pre-production, production and post-production.

During pre-production, I worked closely with the director, the production designer (Bill Brezski), the DP (Dan Mindel), the AD, and the SFX supervisor (J.D. Schwalm). I’m also interfacing with the various art director and concept artists (set, vehicles, creatures/characters) at this point, because everything they design will involve a visual effects entity. Also in the mix is my interaction with Joel Harlow, the creature designer tasked with Krampus – we would have to strategize how much was going be digital or practical. Decisions made in pre-production have long term ramifications. One of the wisest decisions we made in pre-pro was to go with a mostly practical approach to Krampus. Using Tim Curry’s performance in Ridley Scott’s Legend as a creative touchstone, we wanted Kristofer Hivju’s performance from practical photography to drive the performance – rather than going full CG with facial capture/animation. I worked with Dan Mindel on in-camera techniques to convey Krampus’s 10 foot size, combined with help from Key Grip Joe Macaluso’s team that built ramps and platforms to elevate Kristofer to nail down the eyelines from the other actors. Aside from the SFMU/suit build, the plan had minimal impact on the production shoot days, and in post we used additional 2D techniques to help his scale and augment some performances – but a trivial effort compared to if we had decided on an all CG approach. As the art department further developed the designs of their sets, it would become apparent how much digital help they need in terms of extensions ( they were significant, as it turned out – the North Pole City ended up being more than 100 square kilometers ).

Previs of major sequences was carried out during pre-production. Alex Cannon and Dan Heder led teams at DNEG and Torchlight to design sequences, resulting in highly fleshed out roadmaps for Imageworks and Rodeo to follow as they developed assets and workflow for their sequences. Integrated into this process was Greg Rementer, the Action Unit director, augmenting the previs with practical StuntViz from his team to ground the interaction between creatures and humans. We spent about 16 weeks planning the shoot, requiring extensive meetings to go over every aspect of key sequences so all depts were clear on their roles and what was expected of them on the day. The calendar for each shoot day was detailed out to an extraordinary degree – every piece of equipment and person required for that day’s work was indicated, and I needed to be aware of every aspect relative to the visual effects requirements for the shoot. This meant having available the appropriate previs or concept art, or ensuring e creature proxies were ready for reference.

The production phase began in October 2023 and was filmed mostly at the OFS Facility outside Atlanta, a vast abandoned fiber optic assembly plant with almost 300,000 sq. ft of interior stages. On these stages were built the interior of the North Pole hangar, Nick’s weight room, the interior of Jack’s apartment, and various set pieces. At OFS was an expanse of exterior parking lots housing one of the largest exterior green screen areas in the world. The Aruba set – for the Snowman battle – was basically a swimming pool constructed on the parking with palm trees brought in from (where). The North Pole center square was a rudimentary set build on vast U-shaped wall of shipping containers shrouded in bluescreen, originally constructed the Black Panther.

Over 70 days we filmed about 120 scripts pages of material, methodically slogging through the plans devised in our pre-production meetings. It’s a given that surprises occur during production photography. An old military adage is “No plan survives first contact with the enemy”. In film production, I’ve found that the enemy is almost always time. Every department during photography will need the help from the VFX dept, in aspects that’s impossible to expect.

Sound Dept: “Can you paint out the microphone on the costume? They want to shoot now and I need 10 to rewire it.”

Art Dept.: “Can you clean up the sleigh? The body’s warped from the rain and now it looks like it’s falling apart, and we need 2 days to repaint but we’re shooting it after lunch.”

Creature Dept.: “The Fish is in at urgent care, she has an allergic reaction to the latex so she can’t wear the costume. Can you do her full CG?”

Set Dec: “They moved the camera to a much wider shot, and we need 30 minutes to dress in the snow but they want to go now, can you add it post?”

Props: “We need to put a plasma arc in the container, but my stuff didn’t arrive yet and they want to shoot it tomorrow. Can you…”

And so on. This is why my VFX Producer has learned to have in her budget a six-figure line item called “Misc. Production Fixes”

In March 2023 we began post-production in Burbank, California. The editors, Jake, and the VFX dept occupied a generic office 2-story building off a quaint high street. Our dept worked 12-18 hour days for about 60 weeks to finishing the film. During that time I think we ate lunch at my desk almost every single day. We had hired facilities in Los Angeles, Vancouver, Melbourne, Montreal and Stuttgart. Per DGA protocol, the director has about 10 weeks to create his first cut of the film before presenting it to the studio. During that time, there is the process of POST-VIZ, a stage of the VFX workflow that is dreaded and reviled.

Post-Viz required our dept to provide a passable version of every VFX shot in the director’s cut, so the film was coherent. Without this effort, the film would be incomprehensible. The crux is that no one wants to wait until the work is done before approving, so it needs to be represented in the director’s cut. It’s usually a mandate that there can no visible blue screen in the director’s cut. Set extensions needs to be created. Creatures – often speaking – need to be created for shots. FX and vehicles need to be animated and comped in. The quandary is that everyone knows it will take more than a year to finish the VFX work to high quality, but a version of almost every shot in the film needs to be provide in 10 weeks. It seems an impossible task – yet it is done on every major tentpole film since… well, since probably Star Wars. Luckily there are companies that have become experts at creating post-vis shots, something a little better than previs and just enough to convey the storytelling aspect of the shot. Some of this companies are previs houses and some VFX facilities provide post-viz versions of their shots for the director’s cut that are adequate for screening. The key to succeeding at post-viz is to plan way ahead. Like a during production, making guesses at what assets need to fleshed out so they are ready for post-viz work. But no matter how you plan, the post-viz process is grueling and nerve-wracking because the director’s cut is the stage where they are finding the film – it’s a time when they are meant to try things and throw out what doesn’t work.

As the cut gets more solid, the post-production work solidifies into a routine of review meetings with the involved facilities, guiding their shot work towards a level where they can reach the state of ‘final’ – where all creative guidelines are met and the shot is technically checked and ready to be passed into the DI.

Could you walk us through the initial concept phase for designing the North Pole?

The North Pole City was one of the most significant design and execution challenges of the film. Bill Brzeski’s concept imagined the city as an ancient one initially focused on hand crafted toys and then – as the world grew – evolved into an industrial centric city was mix of old European and modern architecture. As pre-production ticked away, his team needed to focus on what sets they needed to build, and that task absorbed the team – but those constructed sets were a tiny percentage of what was required to be seen in the various moments in the film, beginning with chase sequence and ending with a climactic end battle in the heart of the city.

Using European cities as a creative touchstone (Paris and Mont Saint-Michel being the most influential), notable designers Christian Scheurer and Rodeo’s own Deak Ferrand worked with Julien Hery to flesh out a staggering amount of detail ranging from street cobblestone patterns to formulating the right combination of old vs modern architecture. The general color temperature of what the city lights was not realty finalized until a few weeks before the deadline for delivery.

What were some of the biggest challenges in bringing the North Pole to life through visual effects?

The biggest challenge was balancing scale and detail. The city had to feel massive yet grounded, with intricate textures for buildings, machinery, and snow effects. Rendering the avalanche during the chase sequence was particularly demanding, requiring heavy FX simulations.

How did you balance the fantastical elements of the North Pole with a sense of realism?

We used photorealistic textures and lighting to ground fantastical elements in reality. For example, the sleigh’s design included visible wear and tear, and the snow effects were based on real-world physics simulations.

How did you approach the lighting and color grading to capture this unique ambiance?

Dan Mindel set the color palette and visual tone with his organic lighting and naturalistic approach to photography. We learned to embrace the optical idiosyncrasies of the anamorphic lens, and we tuned our composition style accordingly. The artists paid close attention to how focus waterfalls through an image in depth, the look of anamorphic bokehs and lens distortion. Much of the grading from dailies was kept intact through the post phase, with on-set CDLs carried into the workflow. Final grading was helmed by Stefan Sonnenfeld at Company 3’s new facility in Hollywood.

How did you ensure the integration of Krampus, the snowmen, and the hellhounds into the real-world environments?

We used HDRI (High Dynamic Range Imaging) to capture on-set lighting, ensuring CG characters matched their environments. Physical props and reference models were used during filming to guide interactions.

Garcia the polar bear bodyguard is such a unique and imposing character. Could you walk us through the creative process behind designing and animating Garcia? What were some of the challenges in bringing his character to life?

Garcia’s introduction in the North Pole, combined with the appearance of the elves, helps set the tone for the mythology for the city. Working from an original concept from Karl Lindberg, Rodeo FX created a bespoke asset. Details such as a tactical harness and ornate metallic embellishments helped integrate him into the world’s lore.

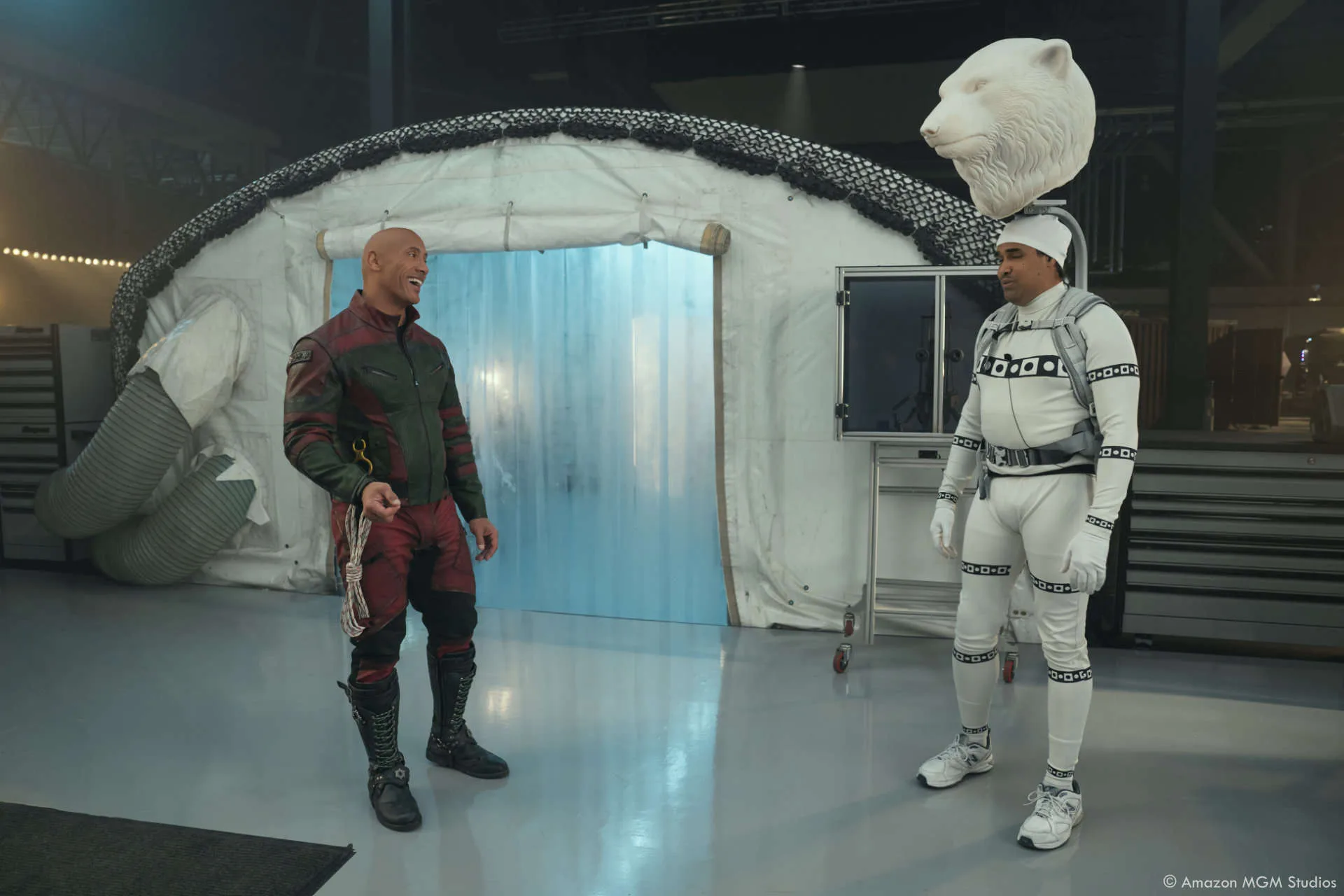

Performance-wise, Garcia’s on-set performance was provided by Reinaldo Faberlie, and his gruff, no-nonsense attitude served as reference for Rodeo’s animators. A 3D-printed, full scale head (based on the digital asset) was printed and mounted on a backpack rig for Reinaldo to wear as he performed with Dwayne Johnson and Chris Evans. This ensured proper eyelines and provided the cameraman with something real to properly frame. Rodeo handled animation, rendering and compositing integration.

The snowmen villains have a distinct blend of charm and menace. How did you approach their design and animation to balance these contrasting elements? Were there any specific references or inspirations you drew from?

Combining whimsy with menace, the ‘Snossassins’ were designed by Aaron Sims Creative, with animation by Imageworks. Their hulking, imposing forms provide a formidable obstacle for our heroes to overcome, but director Jake Kasdan liked the idea that their Achilles’ heel was their carrot noses – an iconic accessory to traditional snowmen.

The movement style was evolved by Julius Kwan, Imageworks Animation Supervisor, He envisioned them a simple movements for them due to the mass if the limbs, within with single-minded lethality.

The hellhounds are quite terrifying in their own right. Can you share how you achieved the look and feel of these creatures?

These creatures don’t have much screen time, but they were probably the most fun to do. Beginning with a design from Karl Lindberg, RISE built a 3D asset and refined the design to incorporate aspects of wolf, hyena and the spines of a porcupine. In terms of tone, they moved with the swiftness and agility of oversized canines.

What is the VFX shot count?

The film included over 1950 VFX shots, ranging from full-CG environments to creature animations.

What is your next project?

I get share that yet.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Rodeo FX: Dedicated page about Red One on Rodeo FX website.

RISE: Dedicated page about Red One on RISE website.

Sony Pictures Imageworks: Dedicated page about Red One on Sony Pictures Imageworks website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2025