Last year, Paul Butterworth talked to us about his work on THOR. This time he explains the wonderful work of Fuel VFX on the film that marks the return to the SF of Ridley Scott, PROMETHEUS.

How did Fuel VFX got involved on this show?

We’ve known VFX Supervisor Richard Stammers, VFX Producer Allen Maris and Fox’s VP of Visual Effects Todd Isroelit for a number of years, and all were very keen to have Fuel involved on the film. We started work early on in pre-production with some concept and look development work for the holographic Engineers and the holotable, and it grew from there.

How was the collaboration with director Ridley Scott?

I attended some of the shoot at Pinewood Studios in London, and Ridley was fantastic to work with. At the time he was filming the Engineer running sequence, and I was very impressed with how focused and calm he was. Between takes, he would take the time to sit with me and discuss his ideas for a shot or a sequence. He would sketch what he wanted and that helped me and my design team immensely when it came to building on those ideas.

What was his approach about visual effects?

For Ridley was all about it looking great. The look was the most important thing rather than whether an effect had a scientific basis or adhered to any particular rules. That’s a good place to start to create great design work. Of course, to make sense of something as complicated as the Orrery we came up with our own rules as to how it should work which we workshopped with Richard, but Ridley wasn’t so fussed about what those rules were as long as it looked fantastic and the bigger story points were being served.

How did you collaborate with Production VFX Supervisor Richard Stammers?

I’ve known Richard for many years, so we’re very comfortable working together. He’s very collaborative and inclusive. Once we got into shot production, he was in LA and I was in Sydney, so we worked mostly via Cinesync where we could workshop ideas and he could provide direction or feedback in real-time. During the concept design and look development phase he was great at providing feedback on the many ideas we were presenting and guiding us on what was most relevant to Ridley’s ideas.

What have you done on this movie?

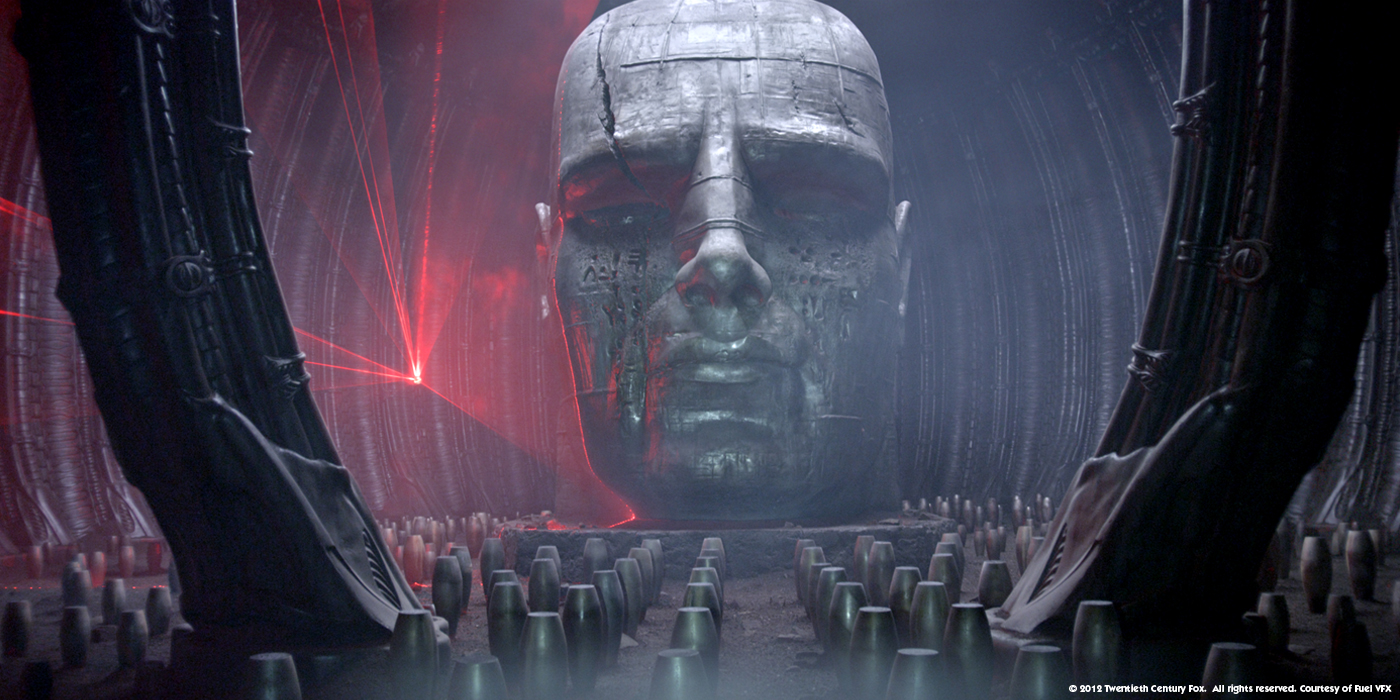

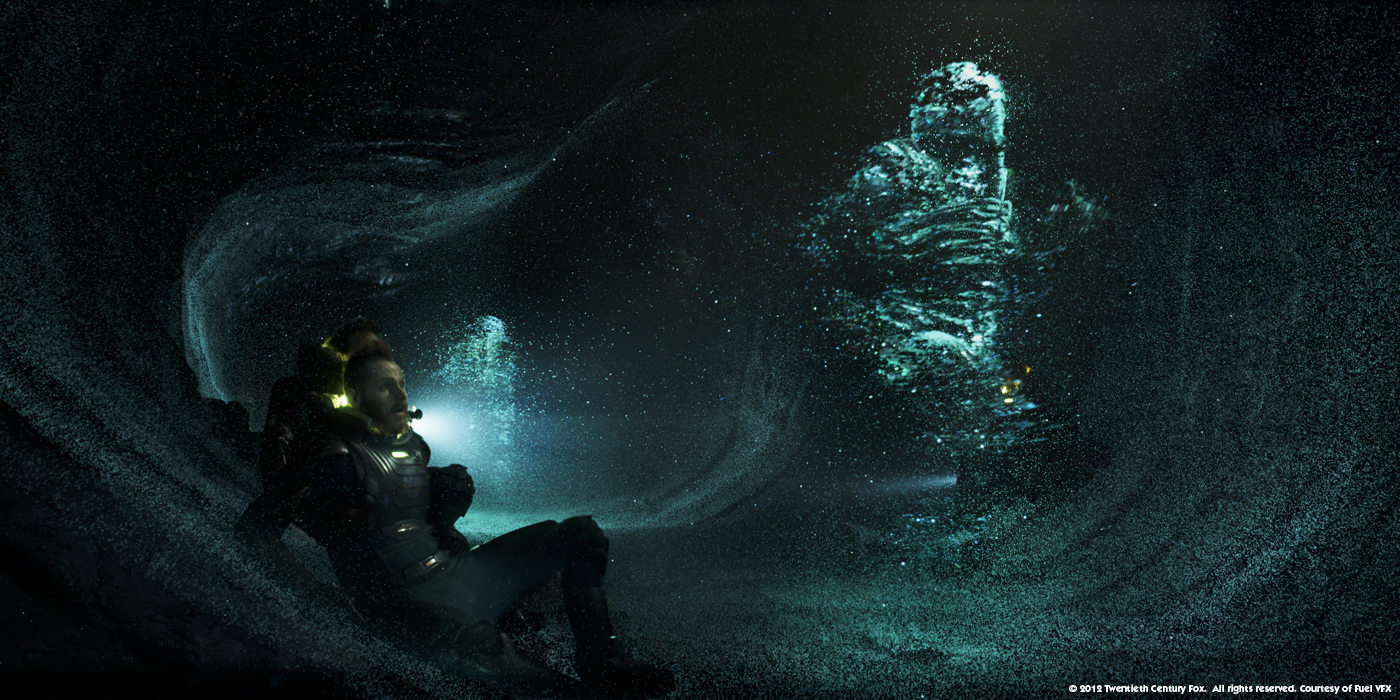

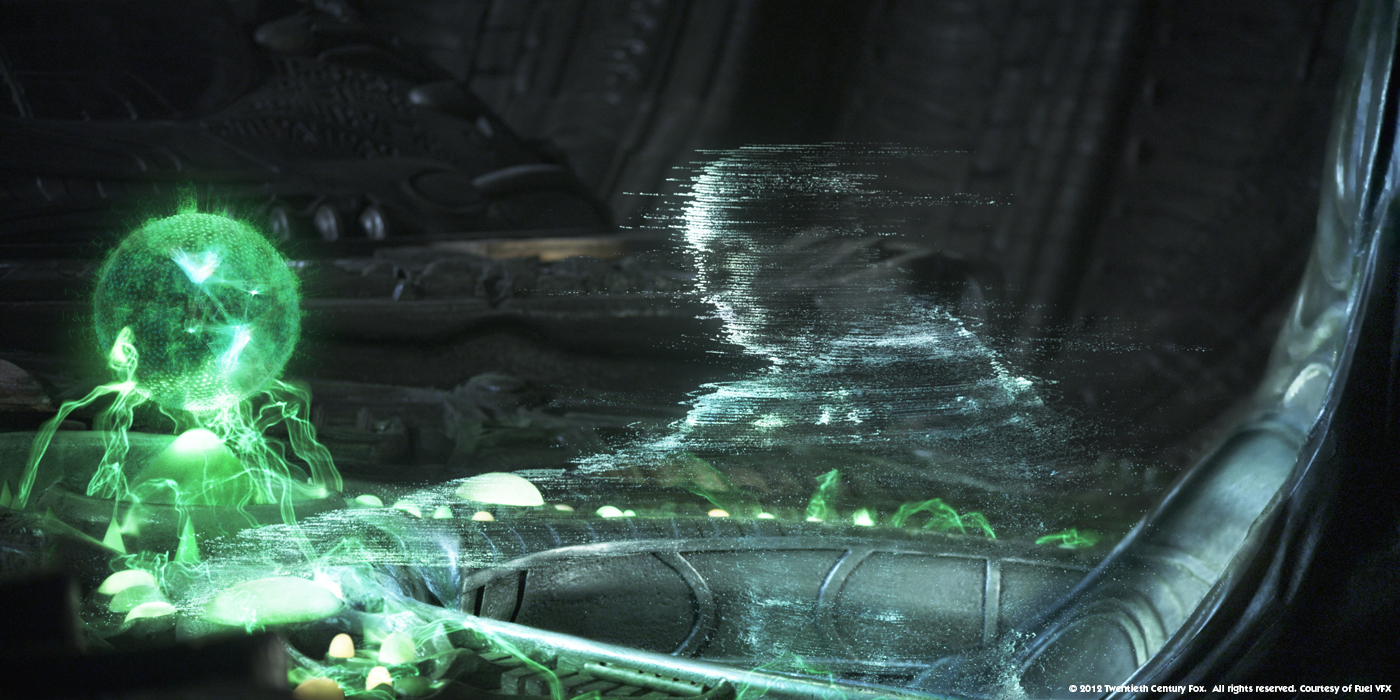

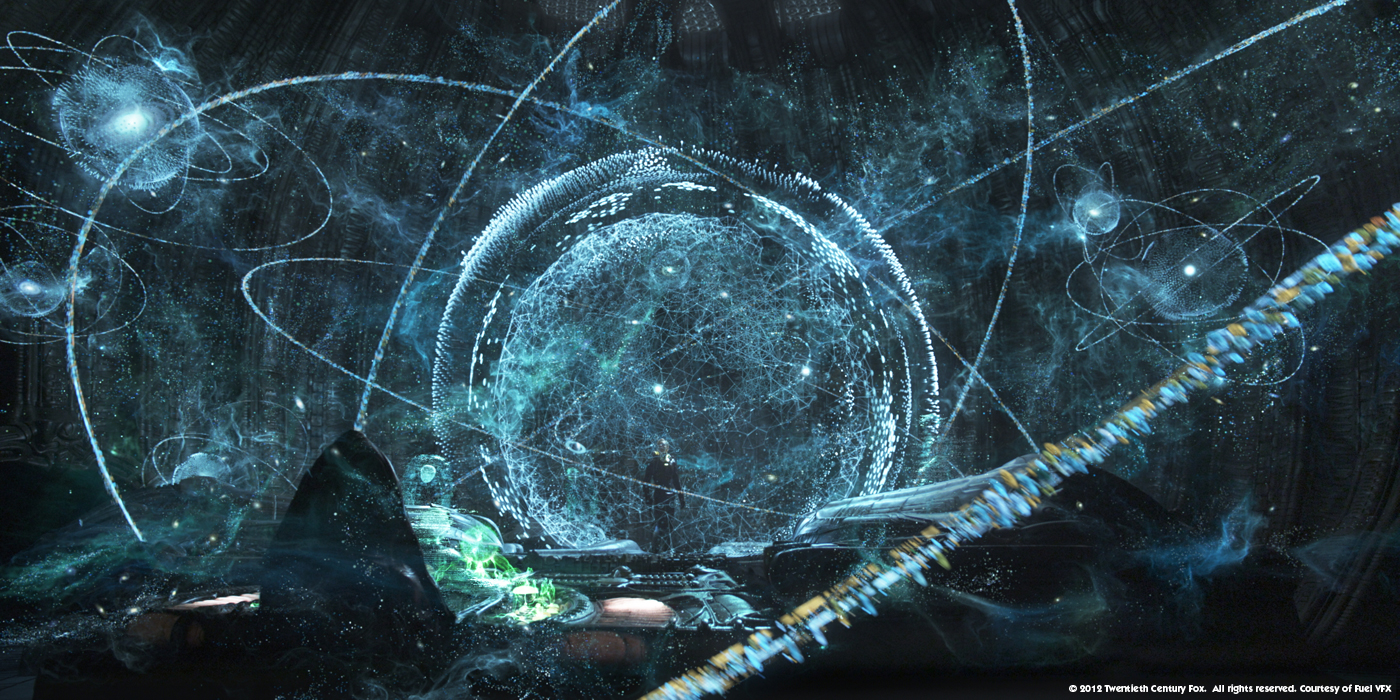

We were very excited to be given responsibility for most of the design-driven visual effects in the film which included some key sequences and story points. Fuel created the effects for the Orrery and it’s control desk energy; the holographic Engineer characters; the holotable on the bridge of the Prometheus; and the laser scanning ‘pups’ – these were all effects that we designed and conceptualized based on Ridley’s and Richard’s ideas and then developed into final shots. We also looked after the set extensions in the pilot’s chamber, the particle-like ‘tunnel effect’ that gets activated in the catacombs, and the 3D holographic screens in Vickers’ suite.

Fifield deploys laser scanning probes. Can you tell us more about their design and creation?

We did a number of styleframes showing how the lasers could look which Ridley really liked, but this effect is really about the motion of the lasers. So the FX department spent some time doing motion tests investigating how many lasers there would be, how fast they scanned, how much they flickered and how much contact with the set walls should be seen. The final look is based on the concept of three forward-facing lasers that map the environment ahead, as well as a curtain-type laser that does finer scanning of the immediate location.

On set, there was simply a prop of the probe for interactive or eyeline reference only which we removed and replaced. Sometimes the prop was suspend from a stick if it needed to hover in a particular place, and at other times they weren’t there at all. And there was never any red interactive light on set – we added all of that.

While the laser effects are primarily a 3D FX simulation, creating these shots were quite challenging for the tracking and comp departments. Given it was a stereoscopic film and the lasers needed to interact with various set, prop and character surfaces, that interaction had to line-up perfectly. There was a lot of hand-painting in comp, and repeated detailed camera tracking that caused some hair pulling and gnashing of teeth but the team pulled off the shots brilliantly.

Can you explain to us in detail the creation of the Holotable on the Prometheus?

The holotable was the first thing we had in look development and Ridley basically approved our first motion test of a tunnel writing on as the final look for that effect – and that’s the look that’s in the film. So we got off to a good start! Then it was a matter of designing the structure of the complete pyramid and having that write on over time throughout the film. We also designed various widgets, readouts and gauges that sit above the holotable. We put a bit of thought into what these might be – vital signs of the crew, atmospheric readings, probe coordinates etc.

At a moment, David activates a hologram that shows the Engineers in various rooms. How did you design the look of this hologram and how did you create it?

The design and development of the holographic Engineer characters was the trickiest of all our concept work. These characters are made from light and yet had to be mysterious and eerie. At times they needed to be an abstract volume of particles, and at other times you needed to be able to glimpse the Engineer. Ridley was especially particular about the look of these characters as they are so important to the film. It was a challenge for us to get these right and we spent a lot of time both in concept artwork and 3D R’n’D in Houdini to get there.

Once we had a good general recipe however we found that the look of the Engineers could vary considerably from shot to shot depending on framing, lens and lighting – mainly in terms of the readability of their volume. Given it’s a stereoscopic film those issues really jumped out. So the Engineers were ‘sculpted’ on a shot by shot basis, by controlling which particles are switched on or off, to ensure they read well in 3D.

Then there was their interactive light to deal with. That was relatively straight forward in the pilot’s chamber where we had a good lidar of the set but it was very difficult in the tunnels. The tunnels had a warm light in them which was unsuitable to the icy blue that the Engineers became, and the lidar we had of the tunnels did not pick-up the intricate details of the hewn rock surfaces very well. So we modeled our own extra detail into the lidar scan so that it had enough detail to create interactive lighting passes from the Engineers, and also used it to change the set lighting to be much cooler.

How did you create the great interaction between David and the holographic Engineers?

We had a lidar scan of David’s body that we used to hold out the particle effects, and his hair movement was filmed in-camera so this was relatively straight forward. The thing we spent the most time on was working out how quickly the particles that wrapped around him dissipated.

The Engineers employs an interactive map, the Orrery. Can you tell us more about this beautiful map?

The Orrery was developed at Fuel based upon the script pages, discussions with Richard, and with reference to a painting from 1766 that Ridley liked called ‘A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery’ by Joseph Wright of Derby. From there, our art department created a series of style frames, taking on board aspects of the different concepts that Ridley liked in each batch until we arrived at a final concept frame.

During that process we received a ‘Ridleygram’ (a simple hand sketch on paper by Ridley) that referenced frog-spawn and showed multiple spheres within the orrery. As the script outlined some sort of magnification function in the centre of the orrery, whereby an Engineer could study a star or planet more closely, we developed the idea that there were also smaller secondary spheres orbiting the centre. The idea being that these smaller spheres are pre-selected parts of the universe that have been magnified to a certain extent and are ready to be moved into the centre to be viewed even larger. The ‘gimble rings’ are a direct reference to the painting but in our Orrery we came up with the idea that the rings would hold DNA data of the galaxies or solar systems that the Engineers had mapped.

Once we had an approved design and motion test, building it was another matter, especially for a 3D stereoscopic production. To achieve it within the production schedule, we needed to rebuild and extend our deep image pipeline considerably. A wide shot of the Orrery has 80-100 million polygons which would be hugely expensive and time-consuming to re-render each time if Richard or Ridley had requested even a minor change, say, to the location of a planet or other single element. But we knew we needed to be prepared for that. So the deep image tools allowed our artists the ability to reach in and manipulate areas of their choosing in an interactive way, so they could re-render and re-comp that particular section only.

Can you explain to us step by step the creation of one shot of the Orrery especially the one with the Earth?

Once the Orrery design was locked off we built it as an asset that had distinct parts: the central data sphere, the rings, the secondary spheres, the outer layer of nebulas and stars (which we called the ‘known universe’), the planets, and targeting system. We quickly developed a low-res version of the Orrery that we used for blocking out the sequence to get approval for layout and animation of the various elements. Once that was approved the edit for the sequence actually didn’t change very much and we concentrated on taking the shots to completion as per the blocking.

The shot of David holding the Earth had a particular challenge because he was filmed holding a glowing white ball as a means to cast interactive light on him. The lighting worked great, however, it was decided a bit later that the Earth should be quite a bit smaller than the ball he was holding. So that shot has quite a bit of tricky facial and hand restoration on David.

What were the indications and references that Ridley Scott given to you for the various holograms?

I think we received only 3 or 4 bits of reference and some Ridleygrams. We were encouraged to come up with our own designs based on initial verbal briefs and worked closely with Richard along the way as we developed these ideas as per his and Ridley’s feedback. It was really rewarding to be given such creative responsibility.

Can you tell us more about the Engineer’s Control Desk?

Early on we were showed a quicktime called Magnetic Movie that Ridley really liked – he didn’t have something particular he thought it could be applied to, he just liked it. So when the opportunity came along to design the control desk energy, I thought it would be great to use magnetic movie as the inspiration.

As usual with our design process, we presented a number of conceptual style frames and Ridley chose one. Based on that, we presented another motion test with a few variations and Ridley selected one of those, so we developed that further and that’s what you see in the film.

Like the probe shots, the biggest challenge with the control desk energy was making sure it interacted with the set properly. Cue more hair pulling and gnashing of teeth. But again the team did a great job.

Have you created some animatics and previz to help the actors on set?

We didn’t create any previz, but we did have a motion test of the holotable scan effect that Ridley loved and he took that to set with him when filming the scene where the pyramid tunnels first begin writing onto the table.

Vickers’s suite features some holographic screens. Can you tell us more about these?

Our brief was that the wall in Vicker’s suite should be a perfect hologram, so it needed to look like the environment was real, as if you could step into it. For the alpine shot, our design team created a matte painting, dimensionalized it, and enhanced it with 3D trees, CG atmosphere and particle snow. We also dimensionalized the wheat field footage and re-created the moving wheat in Nuke.

How did you create the set extensions in the pilot’s chamber?

The set at Pinewood was huge and quite detailed, so we really only needed to top up the Pilot’s Chamber with the top third of the walls and a CG ceiling. There were a number of times we needed to replace the walls in full, mainly when we needed to relight them. We were provided with a great lidar scan of the set, which really helped set-up those set extensions to go through smoothly.

Ridley Scott’s return to SF is something highly anticipated. What was your feeling to be part of it?

It’s been extremely exciting for Fuel to be part of PROMETHEUS, especially having been able to inject a lot of our design ideas into these key sequences. Obviously there’s a rich history in the story, and huge anticipation from the fan base, so it’s also a privilege. Personally, I’m a huge sci-fi fan so it goes without saying that it’s been a dream project for me. Adding to that, working with Ridley and Richard has been amazing.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

Probably achieving the Orrery, particularly the first sequence where David activates it and interacts with the elements within it, as outlined in the questions earlier.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

Probably getting the look of the Engineers right. I don’t think we lost any sleep over it but we maybe held our breaths a bit. We were still trying to get them looking right at a time when we were hoping to be in final shot production but we knew we were on the right path.

What do you keep from this experience?

PROMETHEUS has certainly been Fuel’s biggest undertaking to date. It pushed us, but in a good way. I think we’ve matured because of it, and certainly our pipeline has matured. We’re very proud of the work we delivered and very proud to be associated with the film. Hopefully we’ve been able to show what we’re capable of.

How long have you worked on this film?

If you include the pre-production and design process, about 15 months. But we were in full production for about 7 months.

How many shots have you done?

About 210.

What was the size of your team?

We had about 70-80 people work on it over the course of production.

What is your next project?

We’re working on a few projects at the moment, but unfortunately aren’t able to publicly announce them yet. Our work on PROMETHEUS has certainly brought us a lot of attention which is very encouraging, and we’ve been invited to bid on a few more projects since the release of the film.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Fuel VFX: Dedicated page about PROMETHEUS on Fuel VFX website.

// PROMETHEUS – SHOTS BREAKDOWN – FUEL VFX

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2012

Just to make it clear. The Engineer in the chair is a guy in a suit & prosthetic makeup created by Conor O’Sulivan & not a cg effect.