Lindy DeQuattro worked at ILM for over 15 years. She has participated in projects such as DEEP IMPACT, MINORITY REPORT, HULK or VAN HELSING. As visual effects supervisor, she took care of movies like RUSH HOUR 3, CLONES or THE GREAT GATSBY.

What is your background?

My father started his own semiconductor company in Silicon Valley in the late 1960s a few years before I was born so as you can imagine I grew up around computers my whole life. My brother and I were huge computer game fans from Pong, Zork, and Zelda in the 70s to the Sierra Entertainment games in the early 80s. Those games were really my first taste of combining computers with entertainment. When I was in college I double majored in Fine Art and Computer Science but I wasn’t entirely sure how to combine the two fields together into one career so I decided to go get my MS in Computer Graphics at USC.

While I was in my last year there, a professor from the film school came to speak with our class and said that they were starting a new major in the film school which was an MFA in Film, Video, and Computer Animation. He said they had lots of applicants with an art background but very few computer scientists so if any of us were interested he encouraged us to apply. I did, and I became one of the first 12 students to graduate from that program at USC. While still in that program I worked on VFX for my first feature film called A SAILOR’S TATTOO and then went on to intern at RGA/LA where I worked on MORTAL KOMBAT, and at Sony Hi-Def Center where I worked on RAINBOW. After graduation I got my first full time job at Warner Brothers Imaging Technology (WBIT) and have been working in VFX ever since. PACIFIC RIM was my 31st feature film.

How was the collaboration with director Guillermo del Toro?

Working with Guillermo was about the best experience I think a VFX supe can hope to have in this industry. He is very knowledgeable about VFX and our process and was respectful of the hard work and time that we put into the project. He is also a fan of the industry and what we do, so he was enthusiastic about the work we were showing him. At the same time he had a very strong sense of the direction he wanted to take the project so he was decisive and clear in his directions to us. It allowed us to work very efficiently and at the same time kept the morale of the team very high so everyone was really doing their best quality work. He was very open to our ideas and suggestions. He didn’t necessarily use every idea we gave him since he already had a very strong sense of where he wanted to take the visuals, but if what we pitched fit within his framework then he was very open.

In fact, one of our producers suggested a tweak to the story line where Gipsy picks up the cut half of Kaiju and plans to use that to pass through the breach into the anteverse. We pitched the idea to Guillermo and that’s now what happens in the film.

What was his approach about the visual effects?

When we first sat down with Guillermo he used words like ‘operatic’ and ‘theatrical’ to explain the direction he wanted to go with the visual effects. We discussed paintings and other media that he found inspirational such as The Colossus by Goya and Tetsujin 28 (Gigantor). Guillermo wanted to make the movie that he had wanted to see as a 10 year old boy. It was one of the most creative and artistic approaches to VFX that I’ve ever experienced and it certainly connected for me because of my interest and background in fine art.

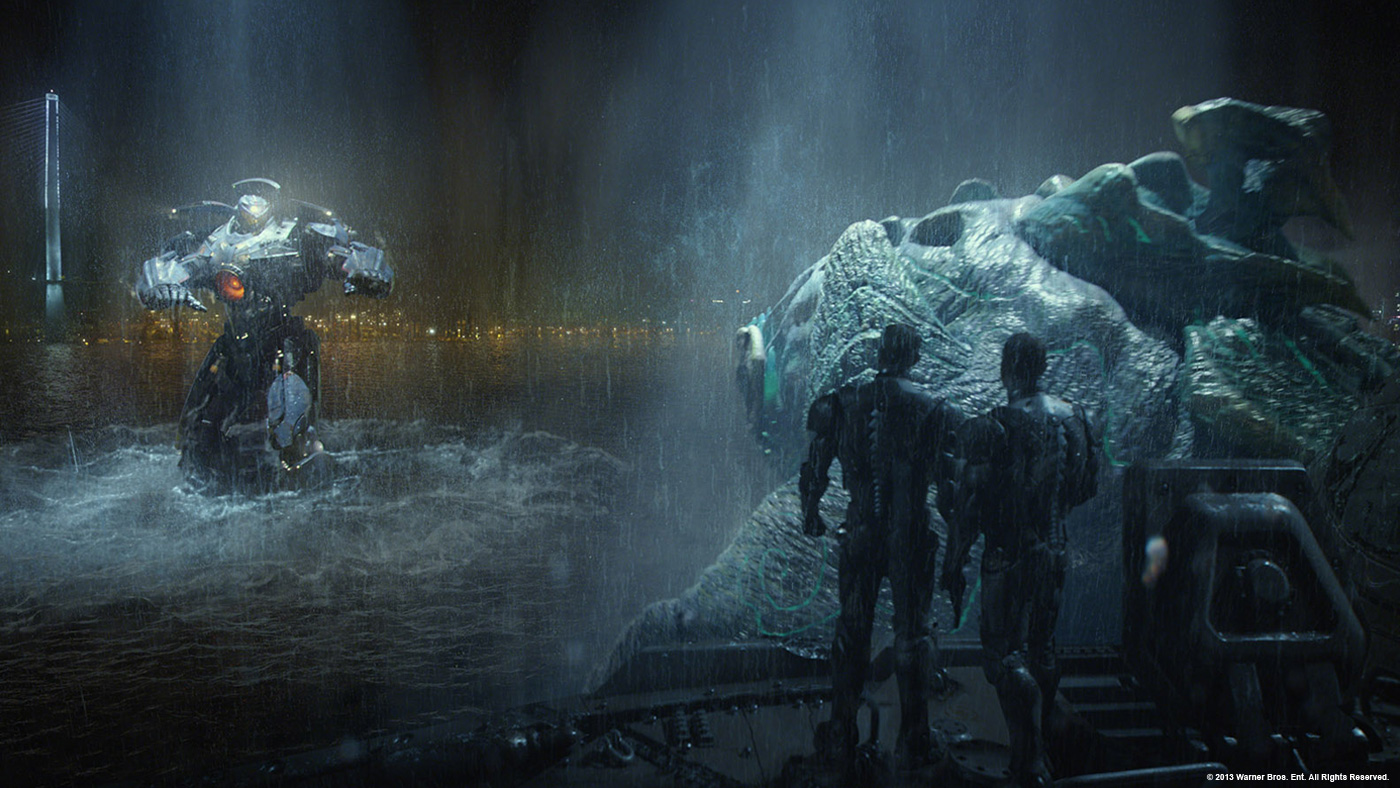

During production we spoke frequently about the composition of each shot, the color story, and the adjustments we could make to direct the viewers eye across the frame. All of these are issues you need to address when painting or drawing. Guillermo really approached the VFX work as if each shot was its own work of art. Guillermo also made it clear that he wanted to pay homage to the old Toho Kaiju movies of our childhoods, but he wanted to take the VFX work to a much higher level. He wanted to get away from the men-in-suits feeling so we decided to go with keyframe animation and to play up the mechanical qualities of the motion over more natural human movements.

How did you split the work with VFX Supervisor John Knoll and Eddie Pasquarello?

John and I started bidding PACIFIC RIM back in March of 2011. That process of bidding and doing the test took about six months before we were awarded the project. Once that happened then we needed to build a pipeline that would allow us to achieve the hyper realistic look that Guillermo wanted while still being efficient enough to bring the project in on budget. John and I worked with all the various department heads at ILM to reconstruct our pipeline for that purpose. It involved several leaps of faith with introducing new software and changing the way we normally do things.

Once we moved into production, either John or I would be on location while the other was back at ILM supervising asset development and pipeline work. When principal photography ended, we moved into post production and at that point we divided up the sequences roughly by vendor. Eddie joined the show and supervised the work done at Base FX in China, which consisted of all the Shatterdome interior work. John supervised most of the work at ILM San Francisco, ILM Singapore, and ILM Vancouver which was a lot of the big battles. I supervised a few sequences at ILM (the end of the Hong Kong fight starting from when Otachi takes flight, the drifts, and the construction site), as well as all the work at Ghost FX (escape pods in Guam Sea, fallen Kaiju carcass, and Hannibal’s Lair and Balcony), Hybride (graphics and HUDs), and Rodeo FX (conn pod interiors, helipad shots, and Newt’s Lab).

What was your feeling while reading the script on the first time with all these huge sequences?

After I read the script the first time I turned to Chris Raimo, the VFX producer, and said ‘I’m exhausted’. I felt like I’d had an adrenaline rush for three hours straight. My next thought was that I HAVE to work on this project. In addition to being a great script and a great genre with a great director, it had everything that I enjoy in VFX: fluid and other particle simulations, tons of creature work, massive destruction, and lots of digital environments… all photoreal.

What was one of your typical day on set and then during the post?

A typical day on set usually meant reporting to set around 5am, start shooting around 6, break for lunch from 12-1 during which time we’d have a cinesync with ILM-SF, and then continue shooting until 7-8pm. After shooting was done for the day we’d have to upload and categorize our data and images captured that day, clean and store our equipment, and send notes back to ILM-SF. We did most of our shooting at Pinewood Toronto Studios which has 8 stages, and it wasn’t unusual for us to shoot on 3 different stages in the same day while another 3 stages were in the midst of set building and dressing.

We usually had two units going at the same time and I would frequently be running back and forth from stage to stage throughout the day to make sure I could monitor what was happening on both units. I was always joined on set by a layout supervisor (either Duncan Blackman or Will McCoy) and two data wranglers so among the four of us we were able to gather the data we wanted and be sure that the shots were being setup as needed to later execute the VFX.

Most of my time on set is spent sitting at the monitor with the director (1st unit – Guillermo del Toro, 2nd unit – JJ Authors) to be sure I can answer questions, understand their intentions for the shot, and then negotiate with the DP (1st unit – Guillermo Navarro, 2nd unit – Checco Varese) to get what I need in the shot without compromising what they need to do with the cameras and lighting. We frequently had four cameras rolling simultaneously on each shot and that certainly meant we all had to pay a lot of attention to several different things at once. Luckily with Guillermo del Toro as director the mood on set was always playful and fun and everybody worked really well as a team. I made several lasting friendships from my time on set.

A typical day during post means starting out with dailies around 9am when the entire crew sits together in the theater and reviews the work from the previous day. While each supervisor (John, myself, Eddie) would lead the discussion for our own shots, the atmosphere here at ILM is very collaborative and we all contributed ideas and suggestions to one another throughout the show. After dailies the rest of the day is generally filled with meetings and artist reviews as well as a possible cinesync review session with Guillermo del Toro where we would present both work in progress and our shots to propose for final. As we got closer to the end of production, we increased the frequency of our reviews with Guillermo from once or twice a week to daily.

Can you explain to us step by step about the creation of the Jaegers and Kaijus?

Guillermo and his team had already done a lot of design work for the Jaegers and Kaijus before we became involved in the project so that was a great help. We started from those designs and then modified them as needed or directed by Guillermo. There are a lot of aspects to the designs that we need to be concerned about that don’t necessarily get addressed in 2D artwork. We need to think about how the creatures will look from every angle, how they’ll look in different lighting environments, and how they’ll move. All of these considerations take time to finesse and it takes collaboration among several different departments to make sure everyone’s needs are met.

Generally we’d start by doing a rapid prototype of the creature, which essentially means we rough the 3D model together without worrying too much about how it’s built. The purpose of this phase is to let us spin the model around and be sure we’re happy with the overall proportions. Once we’re happy with that phase we move into the final model build and paint work. Throughout that process we pass the work in progress to a TD to assign materials, light, and render a turntable. This stage can take several weeks as we review and make adjustments based on the renders.

Once the model is built it moves into rigging. That team, led by James Tooley, worked very closely with Hal Hickel, our animation director, to be sure that the animation team would be able to move the creatures as needed. Finally we had to setup simulations for flesh and fx, and then create several variations of each creature to represent the various stages of damage they incur during the film.

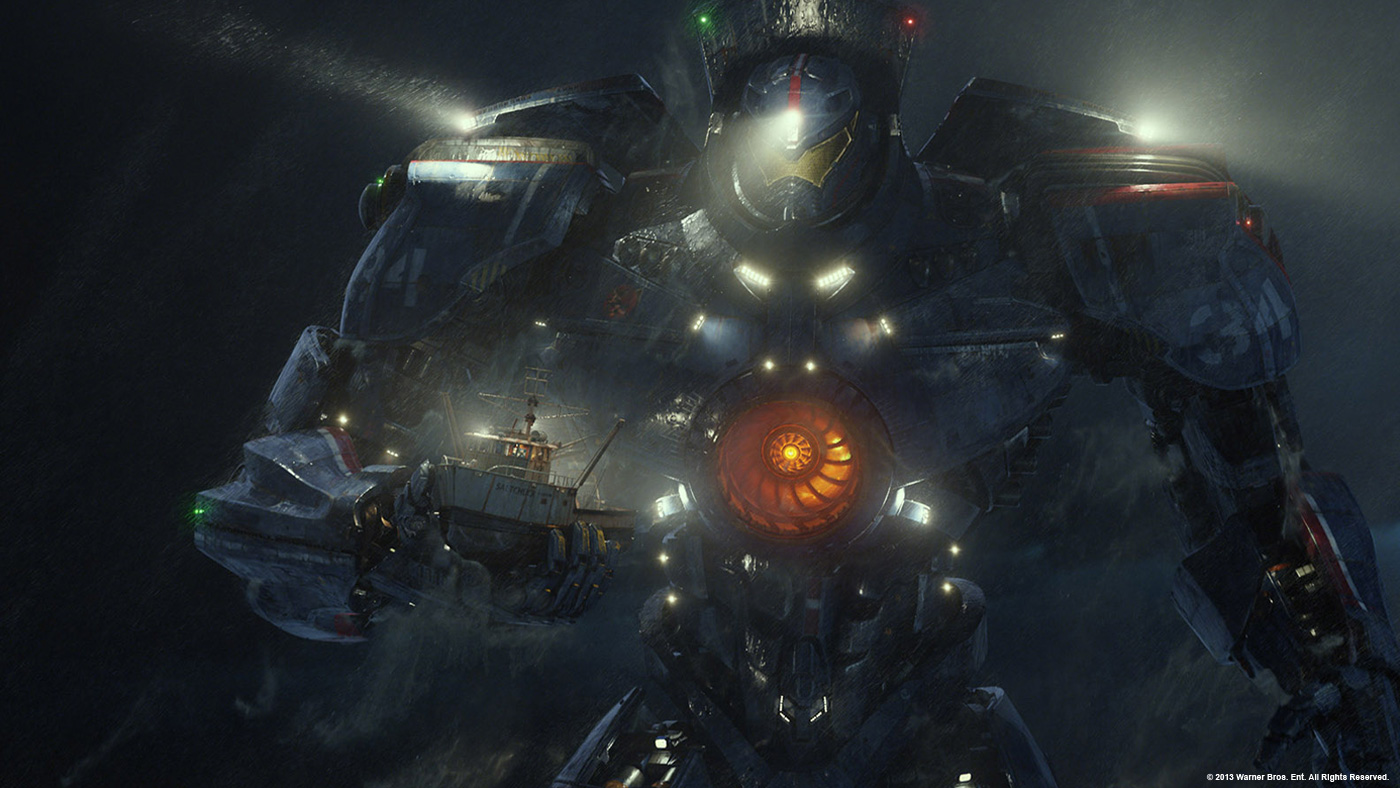

How did you handle the metallic aspect of the Jaegers especially under the rain?

We decided to move to a raytracer for this project for exactly that reason. We felt we’d get better looking metallic surface textures and reflections from a raytracer. This is the first show where we used Katana and rendered with Arnold as our primary pipeline. Our CG supervisor, Victor Schutz, was responsible for many of the great strides we made with our new Katana pipeline. He had previously implemented it for a few shots on MISSION IMPOSSIBLE: GHOST PROTOCOL and we took it to the next level on this project. We setup a procedural ‘running water’ texture to flow over the metal panels. We had rain splatter effects to represent the raindrops hitting the metal surface in the closeup shots, and of course we had water spray off the metal panels as the jaegers moved around.

What was the most challenging aspect with the Kaijus?

The size of the Kaijus was what made them the most challenging. Building a creature that is 250-900 feet tall has many challenges both technical and creative. Our creature model supervisor, Paul Giacoppo, and his team had to build these models efficiently enough that we could manage a shot with 4 or more creatures in it while at the same time having enough detail in a foot or a hand for the close up shots. We had multiple versions of each creature to address that issue and we would load whichever version was appropriate for the framing of each shot. Then in animation we had to address the relationship of scale versus speed. We needed to move the Kaijus slowly enough that they felt massive but not so slowly that the action became boring or looked slow motion. At the same time they are interacting with all kinds of real world physical simulations like ocean surfaces, rain, water spray, dust, and falling objects. If we cheated the motion too much then the physical simulations started to look false. Hal Hickel and his animation team had to strike a delicate balancing act on each shot to get it to work and not feel like a miniature.

Can you explain in details the creation of the water?

ILM has a long history of pioneering fluid simulation effects starting way back on THE ABYSS, moving through PERFECT STORM, PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: AT WORLD’S END, and most recently in BATTLESHIP. We have our own proprietary fluid simulation engine and we light and render water in our own proprietary software as well. We have a small group of artists that specialize in this work and the team on PACIFIC RIM was led by Ryan Hopkins who did an amazing job.

The movie features a large amount of environments. How did you manage this aspect?

Our digital environments were generally a combination of hard surface models and matte paintings. Our digital matte team was led by Johan Thorngren and he worked very closely with our hard surface model supervisor, Dave Fogler, to decide which elements from each environment needed to be actual 3D assets and which could be 2.5D matte painting work. Generally anything in the fg and anything that sustained damage or destruction had to be a full 3D asset and everything else went through the digital matte department. For each of the major locations we were going to be recreating, we started by visiting the real world location and taking lots of survey photos. We also created 2D artwork to represent the final look of each environment. We then set about modeling the elements that we decided needed to be 3D and moved into texture and lighting. Sometimes the asset team set the look for the digital matte group to match to and sometimes vice versa so those two teams had to work very closely throughout the show and managing that interaction was handled by David Meny.

Can you explain more about the impressive bunker of the Resistance?

The Hong Kong Shatterdome was built to hold up to eight Jaegers. It was approximately 400 feet tall. All the work in the Shatterdome interiors was supervised by Eddie Pasquarello and was executed at our partner Base FX in China. We referenced NASA’s Vehicle Assembly Building at Cape Canaveral for inspiration with lighting, props, and finishes. We built a partial set on Pinewood Toronto Studio’s Mega stage which is the largest stage they have and we could only fit a tiny portion of the Shatterdome in it so most of the Shatterdome interior is CG.

How did you recreate Hong Kong?

We started by taking a map of Hong Kong and planning the route that the fight would take through the city. We chose the largest boulevards so that the Jaegers and the Kaijus could fit between the buildings, but even those streets were not quite wide enough so we had to split the streets down the middle and artificially widen them with additional islands and lanes. We then sent a team to Hong Kong to walk that route and take 360 photos every 20 feet or so. We also got up high on whichever buildings we could to get angles from the characters’ heights. We took that data back to ILM and projected the photos onto rough geometry to recreate the city. We then adjusted the building placement as needed, swapped out the projection buildings with full 3D assets wherever necessary (fg and destruction).

Because the Hong Kong city skyline at night consists mostly of neon lights and reflective surfaces like metal and glass, we could use the stills we shot as the base of our textures but needed to move to CG to get the final imagery.

The scale of the fights are really huge. How did you handle so many elements in CG?

Large scale VFX work like this is something that ILM handles very well because we have a lot of specialists and we’re able to have individual teams focus on specific elements of the shot. We had a team for environments, a team for hard surface assets, a team for creature assets, a team for layout, a team for animation, a team for fluid simulations, a team for rigid body destruction, a team for flesh simulations, a team for lighting and rendering, and a team for compositing. This way John, Eddie, and I were able to focus on the big picture of the overall shot look and design and we could rely on the individual department supervisors to make sure their elements were working correctly.

Can you tell us more about the rendering pipeline?

We used a few different rendering pipelines on PACIFIC RIM. The digital matte group generally used V-Ray as their renderer, the water group used Renderman through our proprietary lighting system, and the main creature pipeline and hard surface destruction pipeline used Arnold through Katana. This was the first show where we used Arnold as our primary renderer and there were certainly some growing pains. Michael DiComo was our digital production supervisor and he was in charge of creating and maintaining the pipeline for this show.

There are many destructions during the fights. Can you explain more about it?

This was the first show where we attempted to use Houdini instead of our proprietary destruction tools. Because Houdini was new to ILM we didn’t really have any experts in house. We tasked a couple of our best CG Supes, Micahel Balog and Pat Conran, with implementing our new Houdini pipeline.

Since we were starting from scratch it took a while to get the pipeline up and running, but in the end we found that it was great for most of our midground and background rigid body simulations. We did find that for the most hero destruction specifically the interaction with the Jaegers and Kaijus in the foreground, we needed to pull those back into our proprietary system to have the control we needed. I’m hoping we’ll continue with the Houdini pipeline on future shows because I think there is more we can gain there if we have some more time to put into it.

Can you tell us more about the use of ILM’s Plume and Fracture?

We used both ILM’s Plume and Pyro packages for our smoke and fire simulations. Plume was implemented through our own proprietary software while Pyro was used through Houdini. John Hansen was our lead smoke FX Sequence Supervisor and he found there were pros and cons with each pipeline. Being CPU-based, Pyro was able to run sims with massive grids using 40GB of memory and the solver was very flexible. Plume on the other hand was much faster but because it was GPU based it maxed out at about 3.5 GB of memory. Plume ended up being used in most of our heavy building destruction because our artists were most familiar with it and it took a while to get our Houdini/Pyro pipeline up and running but I suspect we’ll be using more Pyro in the future.

Similarly with Fracture, we have a few different ways to fracture our assets for destruction and rigid body simulations. Our rigid sims supervisor, Michael Balog, and his team used both Houdini and our in house software, but in some cases we needed that fracturing to be more carefully art directed and in those cases they used our in house tools to actually draw the fractures exactly where we wanted them.

Have you used models on this show?

We used miniatures on a few shots for PACIFIC RIM. We worked with 32ten Studios for all our miniature work. Their team was led by model supervisor Nick D’abo, SFX supervisor Geoff Heron, and cinematographer Marty Rosenberg. They created a ¼ scale office building interior for the fist punch shot. They used a high-pressure pneumatic ram to approximate the destruction caused by Gipsy’s fist as it moved through the building. Then they built a full scale cubicle for the end where the fist taps the chair and the screen saver goes off. If you look closely you can see little photos of Guillermo and John Knoll sitting on the desk. We also built a small portion of the stadium that Gipsy crashes into as she falls back to Earth at the end of the Hong Kong fight. We built seven rows of seats at ¼ scale and hit them with a blast of air and particulate to look like turf. Finally we shot several elements such as the dust roiling down the street after the stadium hit, several panes of breaking glass, underwater bubbles, and lens flares.

How was split the work between the various offices of ILM?

In general, we kept the very hardest work here in San Francisco because we have the most senior artists and the largest number of staff artists so we know we can cover all disciplines. San Francisco did 432 shots including most of the Hong Kong fight. Our Singapore office did 163 shots including a lot of the underwater battle, and our Vancouver office did 190 shots including the end of the Hong Kong fight sequence.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

The scope of the project was certainly daunting. The number of shots, the number of creatures, the amount of FX work was all overwhelming if you looked at the whole body of work. We basically just dove in and started breaking it down into manageable sized pieces so that we could get a grasp of what needed to be done. I give a lot of credit to our producers, Susan Greenhow and Erin Dusseault, and their team for staying on top of the schedule, the budget, and the crewing. That’s really what kept us on track.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

It would change from week to week. There are always problem shots that either aren’t moving along as quickly as you’d like or that Guillermo wasn’t happy with. It doesn’t really worry me too much until the very end of the show when you know you’re running out of time. During the last month of the show we’d have daily meetings to discuss our ‘worry’ shots and we’d brainstorm ideas for how to get them back on track. Sometimes it’s the simplest shots that end up being the hardest just because you never really planned for them. The super complicated shots always get a lot of attention and planning and they get assigned to the most senior artists so they tend to go pretty smoothly. It’s the ones that you never bothered to think about that end up biting you. As frequently happens in VFX, the compositors are the ones who suffer the most when a shot goes awry because they somehow need to make it work with the elements they have. Jeff Sutherland, our compositing supervisor, and his team did an amazing job with all our shots including the ‘worry’ ones.

What do you keep from this experience?

I think VFX is always a bit of a balance between science and art. Depending on the project and the director the pendulum can swing a bit further one way than the other. Guillermo really encouraged us to focus on the art and let the science take a supporting role. Here at ILM we sometimes bias our work slightly the other way so it was a wonderful experience to be able to really dig deep as an artist and not worry so much if the physics aren’t exactly correct. I’d like to remain open to that in the future.

How long have you worked on this film?

I started working on PACIFIC RIM in March of 2011 and delivered my last shot in May of 2013 so I worked on the film for just over two years.

How many shots have you done?

ILM delivered 1566 shots for the film.

What was the size of your team?

We had about 500 artists across ILM in all locations but we also partnered with Virtuos, Base FX, Rodeo FX, Hybride, and Ghost FX so there were a couple hundred more artists across those companies.

What is your next project?

We have several projects in the bidding stage right now, but I’m not at liberty to discuss them at the moment.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

The original STAR WARS Trilogy

LOGAN’S RUN

TRON

BLADE RUNNER

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– ILM: Official website of ILM.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2013