Luke Millar discussed Weta FX’s work on Mortal Engines in 2018. Following that, he went on to work on Jungle Cruise and Thor: Love and Thunder.

Dave Clayton started his journey in visual effects at Weta FX in 2003, contributing to The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. Over the years, he has worked on major projects such as Avatar, The Hobbit trilogy, Rampage, and The Tomorrow War.

How did you get involved on this film?

Luke Millar // I first became involved in Better Man after a meeting about upcoming work at Weta FX where some of the previs work was presented. The presenter was from the US and had no idea who Robbie was! I was captivated by the premise and having grown up in the UK during the era in which the movie is set, I put my hand up straight away to be involved.

Dave Clayton // Like Luke, I had a 3-year involvement in the project, starting out with the previs supervision, and then leading into the animation supervision of the final shots.

How was the collaboration with Director Michael Gracey?

Luke Millar // Michael is a creative powerhouse and fantastic collaborator. He is so driven by the visual and emotional elements of a scene, and really pushed us to reach new levels within our work. We developed a great level of trust and an awesome working relationship and I would work with him again in a heartbeat.

How did you organize the work?

Luke Millar // Early on in the project, director Michael Gracey and I talked about the importance of not focusing and key shots and working things up before fleshing out the whole scene. Michael was keen on prioritizing a broader, less progressed version across more shots to ensure that the scene worked after we had started to layer in the ape. I then spoke to the team and said that the initial presentation for any given scene would be the whole thing! We re-structured the entire way we work on movies but it enabled both us and Michael to really focus on what was important or not working rather than spinning wheels on details. Breaking it down like this really helped with planning out the entire schedule and delivery of the movie.

How did you conceptualize the design of the monkey to reflect Robbie Williams’ personality while keeping it believable?

Luke Millar // Imagine a sliding scale with a chimp at one end and Robbie Williams at the other. We knew we were going to land somewhere on that scale but wanted to avoid the uncanny valley. Michael really wanted to capture Robbie Williams’ likeness and so initially we pushed it too far towards the human end of the scale. We landed on a hybrid approach where we leaned 100% into Robbie’s eyes and eyebrows and then used more distinct simian features for the rest of the face. The eyes are where all the connection and emotion comes from and so it was key that we could convey the full complexity of human emotion.

What artistic inspirations or references guided the creation of the monkey’s body movements?

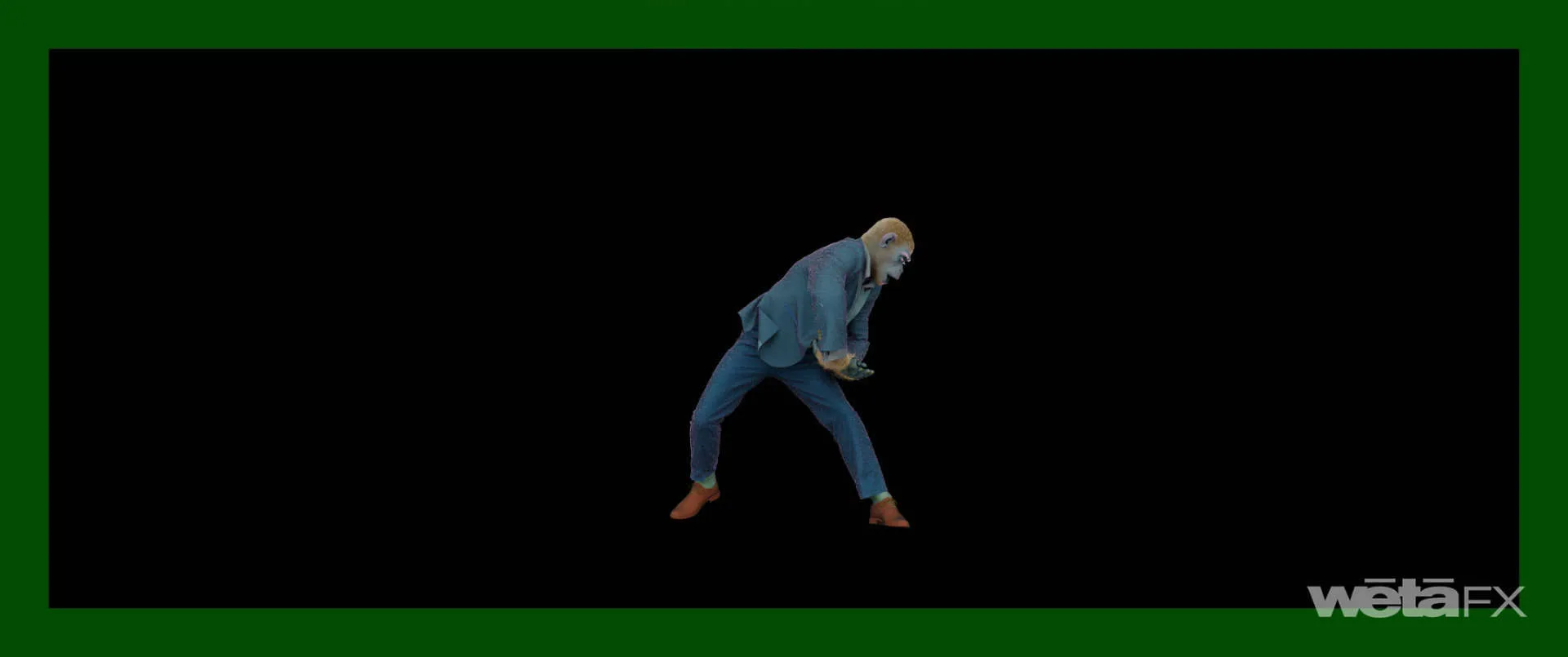

Luke Millar // Robbie’s body performance was predominantly driven by the motion capture of actor Jonno Davies. Although we did experiment with some more ape-like movements in some of Robbie’s more primal moments, it didn’t really work in the context of the film. So we ended up staying true to a ‘human’ performance, which worked well with the proportions we’d decided on for our character – which were fairly standard except for his longer arms, chimp-like hands, and thicker neck. Motion capture still requires a lot of care and detailed work from the artists in our motion team, to ensure the performance is transposed onto our digital character successfully.

What were the main technical challenges in modelling and texturing the monkey to ensure a realistic look?

Luke Millar // Technical challenges involved adapting everyday things to work on the chimp. The way Robbie acts and behaves in the film is ultimately human, just represented as an ape. He has to sport different hairstyles, shave his head, have tattoos, wear different clothing and all of the this had to be adapted to work on a chimp-like canvas. We ended up creating 250 different costumes and 50 hairstyles seen across Robbie’s life.

Were Robbie Williams’ facial expressions captured for the monkey? If so, how did performance capture play a role?

Luke Millar // The entire acting performance was provided by Jonno Davies. Robbie provided that singing voice and VO in the film. However, the ape’s face shapes had to look like Robbie and so we went through masses of reference images and footage from Robbie’s career, matching looks on the chimp character to ensure for example that when Jonno smiles, it looks like a Robbie Williams smile.

Can you explain how you created the monkey’s fur texture to react realistically to light and movement?

Luke Millar // We use a physically-based fur shading model that matches how light transmits through a hair strand. Using physical properties we can dial in the look and, coupled with our physical lighting toolset, we can ensure that the look is as accurate as it would be if a real chimp walked in on set!

Did you face specific difficulties in animating subtle emotions like melancholy or euphoria on the monkey’s face?

Dave Clayton // We created a complex and versatile facial puppet, which was capable of an incredible range of movement and expression. We knew Robbie’s roller-coaster ride of a life was going to play out on this face! If we could replicate Jonno’s onset performance convincingly, we knew we could do this story justice.

However, some of my favorite shots are the most subtle. To achieve the perfect performance in the quieter, more vulnerable moments we still needed to balance all aspects of the face to feel connected, but what you leave un-animated in these cases was more important than doing too much. This restraint allowed the amazing character design and photoreal lighting to sell the moment.

What artistic inspirations or references guided the creation of the monkey’s body movements?

Dave Clayton // Robbie’s body performance was predominantly driven by the motion capture of Jonno. Although we did experiment with some more ape-like movements in some of Robbie’s more primal moments, it didn’t really work in the context of the film. So we ended up staying true to a ‘human’ performance, which worked well with the proportions we’d decided on for our character – which were fairly standard except for his longer arms, chimp-like hands, and thicker neck. Motion capture still requires a lot of care and detailed work from the artists in our motion team, to ensure the performance is transposed onto our digital character successfully.

How much time was needed to develop a single sequence where the monkey interacts intricately with its environment?

Luke Millar // We worked on a rough timeline of 20 weeks from start to finish for a sequence, though that could vary depending on the complexity. “She’s The One” is probably the sequence that required the longest time – almost a year and a half to complete due to the insane level of interaction between Robbie and Nicole!

How did you handle integrating practical elements (like sets) with the digital animations of the monkey?

Luke Millar // We took a very practical approach to integrating Robbie into a real environment. We always shot with Jonno performing every scene so an interaction seen in the film is real and genuine. We created many digital versions of props and would hand over from practical to digital as Robbie handles them.

What challenges arose from animating physical interactions between the monkey and human characters?

Luke Millar // This is by far the most complex work in the film and it has to be correct otherwise it’ll blow the effect. The musical number “She’s The One” where Robbie dances with Nicole Appleton was the most intricate. We made an accurate body digi body-double of Raechelle Banno who plays Nicole and then created incredibly detailed matchmoves for Animation to work with. This didn’t take into account the dress Raechelle was wearing and so we always had to simulate, adjust animation and re-simulate. This would get us 95% of the way there, with hand sculpting taking us the last 5%.

Did you use artificial intelligence techniques to enhance the realism of the facial animation or fur?

Luke Millar // No, we didn’t. We used a facial solver to solve the animation/dots on Jonno’s face but due to compromising his performance or the complexity of the paintwork, the facial cameras were often removed onset. The majority of the shots required the Animation to match the performance by hand using witness/reference cameras

How did you adapt the monkey’s look and animation to reflect the various eras portrayed in the film?

Luke Millar // We ended up with 3 distinct model variants for Robbie: Young Robbie, Teen Robbie and Adult Robbie and then had additional tweaks on top of that. From him putting on a bit of weight during his Knebworth concert to the incredibly emaciated look at his lowest point, we made various adjustments to support the storytelling.

Did changing lighting conditions (concerts, indoor scenes, natural light) require specific adjustments in the monkey’s animation or rendering?

Luke Millar // Erik Wilson, DP on Better Man, wanted Robbie to not be lit specifically as you would typically do, instead choosing to light the space in which he inhabits and letting that light him. This gave an incredible grounded realism to the photography that we really leaned into. The lens kit was comprised almost entirely of vintage uncoated glass and Erik would often shoot into light sources to create very contaminated and flared frames. VFX Sequence Supervisor, Keith Herft, did a comprehensive lens flare shoot and rebuilt every lens digitally so that we could always integrate Robbie back into even the most insane flares!

What challenges did you face in making the monkey believable in nighttime scenes or under extreme weather conditions?

Luke Millar // The musical number “Angels” is set both at an outdoor funeral and during a interior performance of BBC show “Top Of The Pops.” Rain was the mechanism that linked the spaces and SFX created practical rain in both sets. To get Robbie integrated into the space we ran FX particle simulations to hand to our Creatures team to simulate Robbie’s hair moving as the rain hits it. This same cache was also used in our shader pipeline to detect hits on Robbie’s shoulders and accumulate wet spots through the shots.

Did you develop any specific tools or pipelines to harmonize the visual effects with the atmospheres of the different eras?

Luke Millar // Not so much with eras, but we did develop a toolset to ingest the practical lighting board programming, and to recreate it in the computer for the elaborate concert lighting. In the “Relight My Fire” concert scene, there are upwards of 100 light fixtures. Movement, colour and intensity of these lights are all programmed to a music timecode so that it can be repeated take after take. We took lidar scans of the physical lights to record their position in world space and then shot groups of HDRI’s with banks of light pointed at a centre point on the stage to record max exposure and colour. One of our talented Assistant Technical Directors then wrote a parser to take the information from the physical lightboard and recreate the timing and movement inside Katana to get a 1:1 match with the real-world concert.

The Regent Street long take is breathtaking. How did you plan and execute the seamless blend of live-action footage and CGI to create such a dynamic and immersive sequence?

Luke Millar // This took a lot of planning! Choreographer Ashley Warren blocked out the sequence in a dance studio and then passed instructional videos to our previs team to previs capture the dance. Dave then spent a good chunk of timing prevising the number down a digital Regent Street. Erik Wilson then took the previs and some dancers and mapped out a physical path on Regent Street that took into account all the street furniture that we could move the camera through. I then broke down the whole thing into potential plate split points and techvis’d out the moves for each section.

We rehearsed in London for a week on a sound stage mapped out with the sections of Regent Street then had 4 nights on the street itself to shoot the whole number! In post, we had to reconcile and stitch all the pieces back together, augment the street itself with digital traffic, pedestrians, store fronts and gumballs! The amount of work involved was immense and I think we broke Weta records for the most number of paint and roto tasks on a single shot! The result though is truly stunning.

What specific visual effects challenges did you encounter in recreating Regent Street’s atmosphere, including the intricate details of the architecture and the interactions between the monkey and its surroundings?

Luke Millar // The tight shooting schedule and safety meant that we had minimal traffic on the street. We created period correct Routemaster buses, taxis and traffic. The advertising in Piccadilly Circus is now an insanely bright OLED screen and so that had to be replaced with a 90’s fluorescent tube digital replica. We had control over some storefronts which Set Dec dressed to be 90s accurate but many others we didn’t and so a number of digital window displays were created. There is a little artistic license with the Christmas lights as the angel design didn’t arrive until into the 2000s but we needed them for the iconic Angel Wing moment on top of the bus. We did, however, build them from incandescent bulbs rather than LEDs so that they retained the period feel.

Can you describe the process of creating the concert crowds, in terms of variety of models, animation, and reactions to the monkey’s performance?

Luke Millar // Most of the crowd you see in the film are actually real. We shot concerts in Melbourne and London with a real crowd that was there to see a Robbie Williams concert. We hijacked the gig for a couple of takes to get the shots/plates we needed. The one exception was recreating Knebworth, where the crowd numbered 125,000 people. We did get 2000 extras on the day which covered a large area around the stage but the wider shots have digital crowd extensions. We motion captured performances from some of the Weta team’s biggest Robbie Williams fans (including one Dave Clayton!) and then started layering in the performance based on the archive footage we had as reference. There is a lot of dynamism in crowd movement based on how long it takes the sound to reach the various areas of the space and the time it takes them to react so Massive artist replicated all of that amazing detail.

Were there any memorable moments or scenes from the film that you found particularly rewarding or challenging to work on from a visual effects standpoint?

Luke Millar // Yes! The finale in the Royal Albert Hall was shot in two locations. Robbie, the stage, orchestra and floor area were all shot on a sound stage in Melbourne. The rest of the venue was shot during a live Robbie Williams concert almost a year later. We had pre-planned camera positions and ensured that those seats weren’t sold to the public. Then we had to condense the 9-minute musical number down to 4 minutes and cover all the crowd eyelines and lighting scenarios within that timeframe. We set up a series of coloured lights to direct where to look along with a voiceover for what the action needed to be. We had two nights to get every plate but the first night was a write-off after the public got too drunk! It left just a single take to achieve all our hopes and dreams and we did it!

Looking back on the project, what aspects of the visual effects are you most proud of?

Luke Millar // There is one thing that always stands out and that is the consistency of the work across the entire film. There are 1968 VFX shots in the movie which is about 95% of the film and Robbie is so central to every scene that every shot had to be perfect otherwise it would bump audiences out the movie. It is visual effects hiding in plain sight.

How long have you worked on this show?

Luke Millar // I first got attached to the project exactly 3 years ago!

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Weta FX: Dedicated page about Better Man on Weta FX website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2025