Marcus Taormina began his visual effects career more than 10 years ago. He has worked on many movies like THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN, FURY, TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: OUT OF THE SHADOWS and BRIGHT.

What is your background?

I am a VFX Supervisor who has a background in computer science, film studies and photography.

How did you get involved on this show?

As I was finishing BRIGHT for Netflix, I started inquiring about future projects. At the time, BIRD BOX was on the radar, but it had a delayed start. When I returned from a family vacation a month later, I got that phone call asking if I could hop on a plane the next day to scout a river as a consultant. The next week I was on the show full-time.

How was the collaboration with director Susanne Bier?

Collaborating with Susanne was a very unique experience.

That’s her feature involving so many VFX. How did you help her with that?

Just like all of my projects, I like to discuss the technical and creative challenges with the director up front to explore how visual effects can be used to support their overall vision or technical hurdle. Susanne was up front with me from the very beginning that she wasn’t familiar with using VFX as a support mechanism, and entrusted me to approach her with ideas or examples of when it would be useful. As there were a handful of scenes in which we knew VFX would need to be utilized, I did my best to explain the process and best practices ahead of time, and walk her through it on the day.

In post as I honed in on a visual style and look based on our discussions, I would often slug in rather progressed shots into the edit and wait to hear from her. If she didn’t have any creative notes, I would work towards final on those shots, and present those final versions to her and the filmmakers for buyoff.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

David Robinson, my VFX Producer, helped determine VFX vendors and shot assignments that involved a consideration of many variables, some creative or technical and some specific to costs or schedule. On BIRD BOX, I worked closely with him to determine our primary facility, ILM London, as well as four additional facilities brought on later in post as our scope of work increased. David was also an integral part of managing the day-to-day assignments of our crew based on each day’s needs.

There is a big mayhem sequence. Can you explain in detail about your work on it?

The car crash, with the exception of the interior coverage, was all in camera footage with stunt performers. In post-production, we ended up adding a bunch of additional CG dust and debris to give that extra violence to the shots. We also did extensive clean-up and background reconstructions in the shots leading up and immediately after the crash due the multi-angle coverage on the stunt. The interior coverage of Malorie and Jessica was shot on a green screen stage utilizing a rotisserie rig that was mounted to the back of the Wagoner. Because the background plates for this scene were shot before the foreground footage, some additional digital construction had to happen in post-production to make them fit within the final selects. Peppering some of the CG dust and debris on the exterior along with some splintered windows helped meld the footage together in continuity.

Most of the explosions in the scene after the Wagoner crashes were practical effects that we ended up enhancing with computer simulations in post-production. One of the more impressive and seamless simulations occurs directly after Jessica is hit by the garbage truck. After the edit had been assembled, there was a discussion about how, as an audience member, we could be okay with Malorie not running to her deceased sisters side and instead running to save herself. In the end, the filmmakers decided the best solution was to have the garbage truck explode. Expanding on that idea, I decided the best solution was to enhance a large explosion in the plate, but add a combination of 2D and 3D elements to not only sell a large explosion, but also create a fire debris field that would prevent Malorie from running down the road. In the end, we did just that, and what you see in the final product seems enough for anyone to not second guess Malorie’s decision.

Jessica’s death was something that, up until the day of shooting I was hoping we would be able to pull off with a 2/2.5D solution. It became apparent on the day, however, that we would need to create a digital Jessica for the takeover. The final product is a combination of a multi-element pass with some cleanup along with a stunt performer to digital takeover of Jessica just before impact along the CG gore. Interestingly, one of the first computer simulations that was done on the digital double caused the hair to blow back over Jessica’s digital face and, in a normal circumstance, I would ask to re-sim to preserve the actresses face, but for whatever reason I felt this version felt real; this is the final piece we see in the movie.

Lydia’s death was one of the more prolific scenes that stood out to me the first time I read the script, so I knew it had to look good, and fire is always a tricky thing. On the day, we had the support of the special effects crew who provided flame and smoke as supporting elements behind and near the flaming car. We added interactive firelight within the car to light the interior to avoid any digital interior recreation, and ultimately to throw that interactive onto Lydia’s face and body as she sits down. On the day, we also had a charred car to swap out for any of the coverage after Lydia’s death. We lidar scanned and photographed this car along with the pristine car and cyberscaned and photographed of Lydia for digital recreation. In post-production, we mapped out the fire and charring timeline and proceeded to build that into the shots. The end result consisted of 10 or so shots of a combination of enhancement and cleanup, reprojections of charring texture revealed over time, and CG fire, smoke and debris along with digital hair and cloth simulations that are singed and charred by the hot temperature as Lydia sits into the burring wreckage. When possible, we utilized 2D elements of burning and dripping debris, but the later half of the sequence was almost entirely created in post-production by the talented artists at ILM London led by Mark Bakowski.

Can you tell us more about your work with the stunts and SFX teams?

Day to day conversations with both Malosi Leonard and Mike Meinardus were had discussing some of the larger VFX sequences including the car crash, Lydia death, rapids sequence and the forest sequence. I’ll touch on some of the river rapids dialogue later.

From a stunts standpoint, the biggest threat to both Malosi and myself was the idea putting his stunt team down these ranging class five plus waters. We both had a very open dialogue throughout the planning process and we both were very clear that we would never put anyone in harms way and that I would take over digitally where practicality was just not plausible or safe. We had multiple ideas floating around about how we could achieve the work, but ultimately his stellar crew accomplished 95% of the footage you see in camera, on location practically. Some of the work we knew we would have to take on from this footage included digital head and face replacements, body augmentation for Malorie, Boy and Girl stunt performers, and wire, rig and safety crew removals to name a few.

Along the way we also had this looming water tank shoot that was scheduled at the end of the shoot. Mike Meinardus has suggested utilizing some of the same equipment he had previously utilized on other shows, and had a good insight into what was successful, and what could have been improved on from a practical standpoint. We pitched a handful of ideas off of each other and arrived at a happy medium where effects would lend us as many practical elements as possible on the day pending they didn’t interfere or add complication to the shots downstream. The final shots that play out in the sequence could not have been achieved if it was not for the vast knowledge and support from the special effects team, art department crew, and 187 visual effects crew members spanning the globe from four different facilities.

How did you create the eyes “infection”?

All of the eyes were fluid based simulations based on the coloration and details found in each of the victims eyes conceptualized through oil and water emulsification artwork. The infections in the eyes were one of the first things that we nailed down from a creative standpoint with Susanne. There was then a secondary exploration into adding some additional redness into the sclera and pass through capillaries but this was ultimately scrapped due to the zombie-like look it created.

What kind of references and indications did you receive for the eyes?

Oil and water emulsification artwork were done before my time on the project, and some of this artwork was even used in our exploratory R&D phase of “the presence” concept, but were ultimately scrapped. We also looked at a ton of different motion reference as we moved into test simulations because I was very specific about the look, movement and viscosity of the eye FX.

The survivors are using birds. Can you explain in detail about their creation and animation?

Our CG Australian Grass Parakeets Donna, Arthur, and William play an important role of signaling the arrival of the villainous “presence” throughout the film. During principle production, we worked closely with the animal wrangler to study and understand the practical parakeets that were used in a handful of non-vfx scenes. We also have the opportunity to photograph these birds, along with a slew of non-hero birds the last two days of production, with a multi-camera, multi angle still photography rig and motion picture camera. This footage, along with the footage from those non-vfx scenes, coupled with an extensive library of grass parakeets and budgies gathered in post-production provided valuable texture, lighting and animation reference to the artists in ILM Singapore, led by ILM London’s Chris Lentz.

In the end, some of the best reference of these bids in panic was found in some of the pre or post roll from principle photography when the birds were settling into the scene. Because I didn’t want the bird’s action to deviate from the norm, we decided to utilize this footage to use as a guide, choosing a combination of both key frame animation and roto-animation from some of the stand out performances of the practical budgies.

How did you handle the feather work?

The feather and groom work was something I was rather obsessive about and the ILM London team worked extensively on bringing that up to snuff. We had a rather hero budgie shot in the scene in which Boy and Girl are sleeping and Malorie hears “the presence” in a vocal form for the first time. Every time we would review that shot, I just knew we could push the dev even further; work on updating the texture of the feathers to see that intricate detail, check the coloration of the breast compared to the practical footage of the following shot, bring more life into the eyes, etc. I think four-to-five months into that shot, I viewed it over and over again against the other shot, and said to my team “that’s it, that’s the one, I don’t think we can get any better than this.”

How did you approach and create the big river sequence?

In the early stages of prep, there was a suggestion to shoot the majority of this action on a section of the Smith River in Northern California during the summer months in which the river was extremely calm. While there were contingency plans in place for Special Effects to provide practical water agitation and sub-surface bubbles for visual reference and interaction against the boat for VFX, the technical difficulties, environmental restrictions, and cost ramifications for a partial or full CG water surface approach was a deterrent for production and the studio.

Ultimately, production swung the first half of the sequence shoot to later in the winter when the water would swell on this free flow river creating the rapids the audience was expecting. This approach, of course, presented additional concerns, most of which focused around the safety of both the shooting crew and the stunt team headed up by Malosi Leonard. Once safety was addressed, the technicalities of the shoot were discussed.

For the majority of the in-camera footage on location for the first half of the sequence, VFX augmented the stunt performers utilizing 2D compositing techniques that became known as “nip-tucking” to retool their bodies to look in line with Sandra Bullock and two six year old children. 2D blindfold patches added to the work, along with the reshaping and removing the safety helmet of the Malorie stunt performer. On occasion, the medium and close-up coverage along with the high resolution deliverable presented the need for digital head replacements. Sandra was digitally cyber scanned and photographed on location. ILM London rigged and rendered a full CG head complete with digital hair and cloth simulation for a handful of shots in the final cut. Finally, a blanket of 2D and 3D atmospherics were composited over these shots to give the sequence more of a menacing tone it deserved.

The apex of the sequence became the most challenging part of the sequence. The tank shoot was slated for the last two days of principle photography. A large water tank was painted blue, surrounded by over 200’ of blue screen and, with the help of the Special Effects crew led by Mike Meinardus filled with 300,000 gallons of heated, tinted water to match the practical footage in the first half of the sequence. The special effects team also provided a pair of air compressions at 750 cubic feet per minute provide omnidirectional water flow, subsurface agitation and aeration along with the ebbs and flows from secondary waves for interaction against the practical rocks, boat and oars that are seen in the final composites. Without this support, the footage would have lacked the frenetic nature it needed and deserved, and the performances from both Sandra and the two children may have suffered. The final shots that play out in the sequence could not have been achieved if it was not for the vast knowledge and support from the special effects and art department crews on the day, and the hundreds of visual effects crew members in post-production.

The background support for these blue screen composites were shot on location in Crescent City. Both static and spydercam array plates were utilized for the 2.5D and 3D approaches. The array run consisted of three digital camera bodies positioned in portrait mode to achieve the most coverage on the vertical axis due to the sheer size of the Redwoods on the Smith River. Multiple runs captured an extensive 360-degree cyclorama used by multiple VFX disciplines in post-production. Ground and aerial based lidar scans were used for reprojection, layout, and match move purposes. Digital stills along with static and boat propelled motion picture footage was captured along the journey in multiple areas of high action for supplemental support purposes in post-production.

In post-production, we hoped we had all the materials and data needed to accomplish the task at hand. Going in we knew we had some rather complicated shots, but we had hoped that we would be able to treat the majority of the tank footage as composites. As the cut developed, we knew we would have to approach some of these shots as 3D builds with water simulations, so we got that process going as soon as we could in the dev phase. The majority of the 3D water and environment shots that are in the final cut were approached in this manner due to their continuity in the final cut. There was so much great stunt footage to work with from a practical standpoint shot on location to support the coverage of Sandra in the tank, but ultimately some of those lacked the ranging water needed, and we of course knew we would need to add the 3D environmental elements to meld the action together in continuity. With both the 3D builds and simulations, we tried to split in elements shot on location. For example, some of the 3D simulations of the water work included a handful of practical elements of raging water that was used to mask the line between CG and practical in certain shots. The environmental builds were based on the ground and aerial based lidar that was then textured and lit utilizing all of the DMP capture on location from both units. When we were able, we stole hero bits and pieces and kissed them into the shots. We tired to be very strategic on utilizing these elements and studying the footage to find other pieces that stood out to us from the location work that would also work to our advantage when viewing the sequence as a whole. When the environment and water simulations were complete, Jan Moroske and his compositing team added atmospherics and water droplets among other elements to marry the shots together.

The final sequence is really intense. How did you manage the trees and vegetation’s creation and interaction?

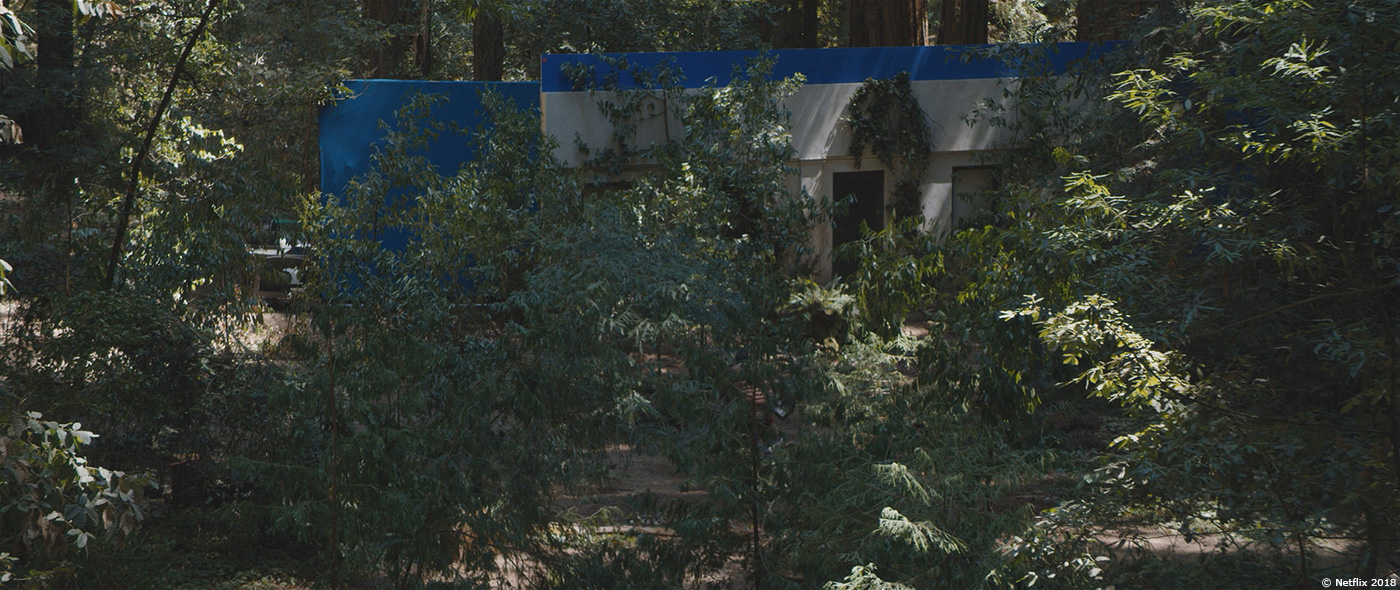

We approached the forest the same way as the rest of the film, collaborating with both the special effects and stunt teams to try and utilize some practical elements. When we arrived on location, we ran some tests for the displacing saplings that included a 400-foot section of wire ratcheted trees and pneumatic cannons that proved successful but lacked that secondary energy that this sequence deserved. On the day we shot, we ran 2-3 takes of the master action as planned, utilizing practical vegetation placed by the greens team and rigged by the special effects team. When Susanne felt she captured the action she wanted in those takes, the company moved to another location while multiple teams removed all of the vegetation that left us with a footpath and some blue stakes with tennis balls that represented the placement of the hero trees that the stunt team interacted with on the beauty passes. Once we were set, and had done multiple lidar and environmental virtual backgrounds as well as extensive set reference, we ran the same action again on that “blank slate” that was ultimately used as our master and reverse master takes so we would be able to have full control of the forest.

In post-production, as the edit became assembled, we knew that in order to have that same feel that the masters had, we would need to reconstruct parts of certain shots digitally. The practical footage of the wire ratcheted trees proved useful from a dev and composting standpoint, and the CG vegetation and foliage was actually modeled after set photography of the native species found in Northern California based on day to day conversations with the botanist and California Parks and Recreation preservation teams.

As you can imagine it took some time and finessing to find that “look” that plays out in the final picture. The biggest challenge with this specific idea that we faced over and over again in this environment was making sure our FX never revealed too much of the pieces behind it, otherwise the audience would pose the question “shouldn’t we be seeing the threat here?!?” I have to commend Pete Kyme the FX supervisor at ILM London for sticking it out on this sequence as we battled it for months to get that specific Atomic Bomb look without revealing what wasn’t there, him and his team really nailed it in the end.

In the end, digital artistry provided the shot specific FX simulations mimicking native photography that also included violently moving CG saplings based on nuclear bomb test footage, secondary displaced CG leaves that tore off along the tree canopy, CG dust and particulate, partial CG background reconstructions of the forest that blend the CG elements into the action plate of Malorie, Boy and Girl, as well as CG set-extensions and additional FX that included dithering ferns, anti-gravity leaves intricate cloth and hair simulations as Malorie arrives at the doorway.

Can you tell us how you choose the various VFX vendors?

Most of the choices made for your heavy lifting facilities at my end usually happens in pre-production. Because of the late start on BIRD BOX, we didn’t make a choice for ILM London until much later into shooting. I had a good experience with ILM San Francisco on a previous project I had worked on, and myself along with some of the filmmakers knew a mutual colleague there who we pitched the idea of joining BIRD BOX to. We had a unique release window that feel within some downtime between their global branches, and found a way to work it out between ILM London and ILM Singapore.

The additional facilities that were brought on for the “non-hero” work I had wonderful experiences working with on past projects, or knew old friends who had migrated together to work at these new facilities, and could trust that the work would be solid.

How did you split the work amongst these vendors?

Once I preview the director’s cut, I usually tend to divide the work based on complexity, continuity, and time frame.

Most of the “hero” work was given to ILM London where we knew we had an extensive skillset and reach. They were to handle the complexity and continuity.

The addition of Scanline Munich was a welcome pleasure based on time frame. Late into post, Susanne and the filmmakers wanted to add additional texture to the scene in which Malorie row’s into the sunken eighteen-wheeler. ILM London tried everything in there power to accommodate this late add, but ultimately ILM LON producer Sophie Dawes told us they would have to pass, but would happily package up all of the elements for the shots they had done work on. We immediately decided that Scanline Munich would be a sound fit due to their amazing Flow-line technology and enlisted them under the supervision of Jan Krupp to help finish around 15 or so shots in that sequence.

Once the fat has been trimmed, you’re usually left with the medium complexity shots that you try to be the most cost effective of splitting up between facilities. On BIRD BOX, I enlisted the artistry of Mammal Studios in Los Angeles led by supervisor Greg Liegey and NVFX led by supervisor Chris Holmes for these shots and sequences.

Can you tell us more about your collaboration with their VFX supervisors?

One of filmmaking’s most important aspects is collaboration, especially if you’re in a creative position like I am. I am very open and up front about this belief during my initial discussions with my facility supervisors and often encourage them to do the same with their teams.

I have to be rather focused on the director’s vision including what they tell me will and wont work for X, Y and Z due to their creative vision, but I do have that window early on to explore some of those elements before the delivery time frame looms over my shoulders. This window is where tend to encourage both the supervisors and artists to play around with the basic ideas and guidelines I give, to collaborate with one another. When I start to see those concepts, FX passes, composites or animations that do and don’t work, I tend to be very up front and vocal about them. To me collaboration tends to weed out the weak ideas and concepts, and get that idea on screen much faster as a potential final.

The vendors are all around the world. How did you proceed to follow their work?

I have to give this one to my team. They worked day and night keeping me on schedule with London, Munich, and the Los Angeles based facilities throughout the project. We tried to be more personable when possible so we utilized video conferencing coupled with cineSyncs, and usually connected on a bi- or tri-weekly basis.

Towards the end when we were churning through iterations of shots, Mark Bakowski and I would do download phone calls in his early morning (6:30am) and my late evening (10:30pm) to make sure we were on the same page before I went to bed. He would then spend that day with his team working on those notes, some of which I would see the next day when I walked in. Now talking about this, I am realizing it was truly an around the clock project!

Which sequence or shot was the most complicated to create and why?

The river sequence proved the most difficult, specifically the rapid journey though their exit. This sequence, from a production and post-production standpoint both technically and creatively was the most complex and took the longest time to complete.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

The continuous design and R&D phase of what would become “The Presence” or “The Creature” in our film.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Creatively and technically one of my favorite scenes in BIRD BOX is when Girl leaves the boat to search for Malorie. The VFX for this scene were constructed and conceived during the post-production phase after the edit had settled. From the very beginning, I had envisioned a tense moment with the creature slowly encroaching on Girl about to overtake her with only the audience knowing just how close to death Girl came. I had a handful of creative discussions with Susanne that proved difficult until I had something visual to show her. The idea of the environmental impact of the anti-gravity tree leaves from “The Presence” came about during the latter half of the creature design phase after shooting. This effect, coupled together with the nebulous shadow creeping onto Girl’s face, along with her static hair and sweater strands standing on end, was one of the best examples of what digital artistry can accomplish with a solid vision.

From an emotional and performance standpoint, my absolute favorite shot was when Malorie mourns the loss of Tom. The empty and raw emotion Sandra Bullock shares with the audience is so powerful. Every time I watched that scene, I felt like I was mourning with her.

What is your best memory on this show?

White-water rafting the Smith River with my entire crew to experience what Malorie, Boy and Girl would in our movie.

How long have you worked on this show?

13 months.

What’s the VFX shots count?

520 visual effects shots.

What was the size of your on-set team?

At peak with both units, we had eight crew members including myself, VFX producer (David Robinson), a second unit VFX supervisor (Mark Bakowski), a hybrid coordinator and still photographer (Melissa Franco), a hybrid coordinator and data wrangler (Hannah Macklin), two match-movers (Sam Gutentag & Lanny Cermak) and one witness camera operator (Mason Moore).

What is your next project?

BRIGHT 2 for Netflix.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

LE VOYAGE DANS LA LUNE or A TRIP TO THE MOON

DAS CABINET DES DR. CALIGARI or THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI

TERMINATOR 2

E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL

A big thanks for your time.

BIRD BOX – TRAILER

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

BIRD BOX: You can watch it now on Netflix.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2019