Andy Brown has been working in visual effects for 30 years. Before joining Method Studios he worked at Animal Logic for 22 years during which he was VFX Supervisor on MOULIN ROUGE, HERO, HOUSE OF FLYING DAGGERS, WORLD TRADE CENTER, AUSTRALIA, SUCKER PUNCH, THE GREAT GATSBY, and THE GREAT WALL.

Todd Sheridan Perry has been in visual effects and animation since 1992. After owning a small visual effect boutique in Venice, CA for nearly ten years, Todd has worked on projects including LORD OF THE RINGS: THE TWO TOWERS, CHRONICLES OF RIDDICK, 2012, THE MIST, and SPEED RACER. He has worked with Method as a CG Supervisor on AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON and DOCTOR STRANGE.

What is your background?

Todd Sheridan Perry (TSP): I’m formally taught in fine arts with a BFA in 2D Media, which includes drawing, painting, photography, and digital media. I moved from Seattle to Los Angeles in 1995 for work in computer games, CG, and logo design. Shortly after I started a tiny visual effects company through which we did commercials, game cinematics, short films, and indie features.

Andy Brown (AB): I have an arts background, studying photography, graphic design and film in London. My background professionally is in compositing and art direction. I moved to Animal Logic in Sydney compositing and supervising lots of commercials and eventually moved into film VFX supervision.

How did you get involved on this show?

TSP: After an enjoyable and collaborative time working with Geoff Baumann on set during DOCTOR STRANGE, I actively pursued being a part of the BLACK PANTHER team at Method when I heard Geoff would be supervising.

AB: I joined Method Vancouver in April 2017 specifically to work on BLACK PANTHER. The main unit shoot was wrapping up in Atlanta whilst asset builds had started in Vancouver and the first trailer was due in a month so it was full steam ahead from the get go.

How was the collaboration with director Ryan Coogler and VFX Supervisor Geoffrey Baumann?

TSP: Collaboration with Geoff on set as well as in post, was just that – collaborative. The times were few and far between that we didn’t have access, either for suggestions, clarifications, or guidance. We were frequently included in creative conversations and were allowed to experiment. Ryan’s voice came directly into the conversation much later in the schedule – mainly because, as the director, he had a lot more departments demanding his time. So Geoff was Ryan’s proxy. When Ryan did discuss things directly, his passion and clarity of vision was a driving force that invigorated the team and reminded us of why we do what we do. Ryan was also open to creative collaboration and was willing to listen to suggestions and alternatives if he felt the new ideas were better to tell the story.

AB: Geoff is a great collaborator; he was very open to suggestions and creative exploration on our end. Ryan joined in on the cineSync sessions towards the end to give us specific feedback on some of the key battle shots featuring Black Panther and the rhinos.

What were their approaches and expectations about the visual effects?

TSP: Geoff comes from an integration background at Digital Domain. He understands the pitfalls when you don’t have enough data from set. So, his wrangling team was gathering everything possible – Lidar scans of sets, photogrammetry of actors, survey data, up to four witness cameras, reference photography, and a constantly updated database of camera and set data driven by iPads. Knowing that anything and everything can change at any point, Geoff was front-loading the production with as much information as possible so that we would have the tools we needed to accommodate. It was also critical that the facility supervisors were present on set, working with Geoff, and helping get eyes on the sequences each facility would be overseeing. Ryan was coming from two features that had little or no visual effects, so a 2500+ shot show was going to be a different experience. On set, Ryan put his faith into Geoff, and ran with the idea that things would happen and it would look great. Once the show moved into post, I think that Ryan got a taste for what can be accomplished, which became a hunger, and then the uncertainty of the possibilities washed away – leaving the desire to tell the best story – and let the artists help make that happen.

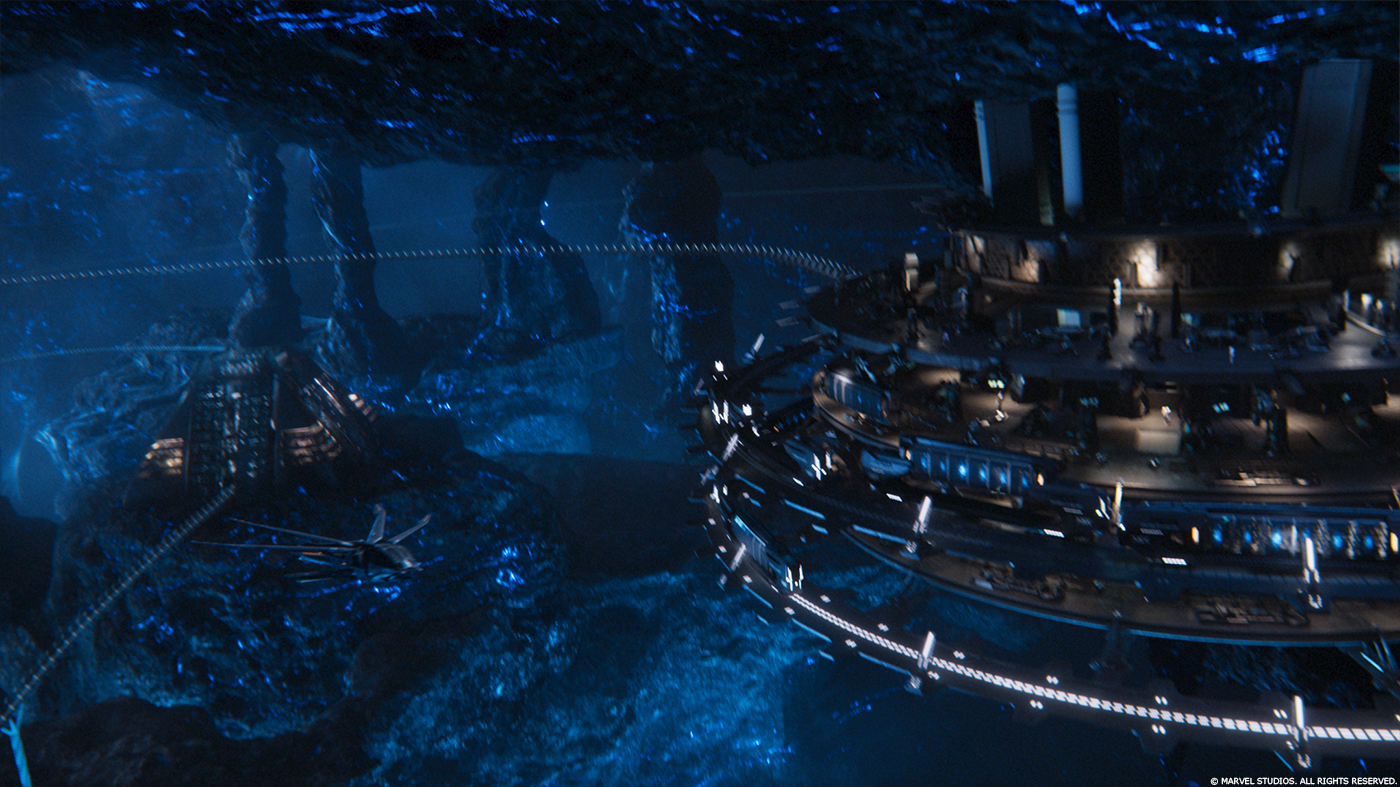

AB: Most of our shots take place in the third act when Black Panther returns to confront Killmonger and the subsequent battle. Method was responsible for overseeing the environment of Mt. Bashenga, the spire and the mine shaft, Shuri’s lab, and views looking down into the Vibranium Mine. The battle sequence was shot on a hilltop location in Atlanta and our job was to extend out from there. We enhanced the battle sequence with digi doubles and three war rhinos, built the hero suits for Black Panther and Killmonger, as well as the Talon Fighter and Dragonflyer aircraft. We also did a lot of creative development for the Vibranium mine, the komoya bead holo, cymatic energy FX for weapons and the suits.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer at Method Studios?

Interesting question. Method originally had a few large set pieces – Mount Bashenga and the Vibranium Mines. So the show was divided as such: we had supervisors in each primary department divided into “above ground” and “below ground.” CG supervisors Chris Ryan and Marc Roth. Lighting leads Sergio Pinto and Jon Shaw. Comp leads Louis Corr and Mauricio Valderrama. And we had key artists for the different areas. Ultimately, the show would grow beyond its original scope, which led to the Vibranium Mines migrating to DNeg. When that move happened, the final battle was divided into “Before Black Panther/Killmonger tackle” and “After Black Panther/Killmonger tackle.”

What are the sequences made by Method Studios?

Method was in charge of the third act battle, Agent Ross facing the Dragonflier (shared with ILM, RISE, Ghost, Cantina Creative), the sunset cliff at the end of the film, T’Challa and Shuri in the lab, Ross being brought into the lab after his injury, Ross and Shuri discussing Wakanda and Vibranium (some cutaways were DNeg), discussion about Killmonger in the lab, and some miscellaneous shots sprinkled throughout, including a suit formation shot in the CIA Blacksite sequence.

How did you work with the art department to design Wakanda?

AB: The art department gave us a magnificent reference manual called the “Wakandan Bible.” All of the research and key images production had chosen for the film were in this document. In it you had references for costumes, the architectural styles for each region, a map of Wakanda, the history of vibranium and its use in weapons, all of it rooted in African culture but infused with Afrofuturism. We used this to guide all of our creative choices and it was a great way to get our crew up to speed with the culture of the film.

Can you explain in detail about the creation of Wakanda?

Method created an area within Wakanda known as Mount Bashenga, a mountain that was formed by a vibranium meteorite that crashed into the earth forming a crater and a high peak with a large deposit of vibranium underneath.

Our CG geography and land forms were based in this idea. On top of the peak sits a spire and landing platform that serves as a fortification and working entrance to the vibranium mine. The primary hill for Mt. Bashenga was based on Lidar scans taken from the hill and set piece for the iconic spire shot on a Georgia horse ranch. The spire itself was a partially built set for the actors to work on — the tower and the mine shaft dropping into the Vibranium Mine would be extensions. The platform for the spire would evolve throughout the show and would be finally all CG in the majority of shots.

To build the terrain we used photogrammetry of Paarl Rocks in South Africa to extend out from the practical set and referenced Ngorongoro Crater for the easterly view looking out to the Savannah below. For views behind the spire looking towards golden city we utilised photogrammetry from areas of Uganda and table top mountain to build the crater and terrain beyond.

The Bashenga terrain was sculpted in ZBrush and placed in Maya – then ported over to Houdini for additional erosion algorithm to add realistic detail into the mountains by Houdini artist Sebastian Marsais, as well as foliage distribution driven by texture and control maps.

Ultimately, the Bashenga and surrounding environment would encompass 3,600 square km and over 50 million trees – in the crater below the mountain alone. The environment would connect to ILM’s Golden City environment. Both facilities shared components of the total area, so that distances would remain contextually sound not only for BLACK PANTHER, but for INFINITY WAR.

Our Bashenga environment team was lead on the Houdini side by Sebastian Marsais, and modelling and texturing in Maya was primarily Travis Smith, Garret Biles, and Eric Zhang.

How did you handle the lighting conditions?

Due to the “windy” weather conditions in Atlanta the lighting conditions would quite often change from full sun to overcast during a continuous beat of action. In terms of CG lighting our first pass obviously would be to match the plate using the provided HDRI light probe. But if the foreground fell into shadow we would add sunlight into the background to sell the idea that it’s a sunny cloudy day. Cloud shadows on the savanna and distant mountains were also added.

Can you explain in detail about the creation of Black Panther and Killmonger?

Both suits were a collaboration between Ryan Meinerding and Ruth Carter on the Marvel side, and were fabricated in numerous layers for both principal cast and stunt men to wear. Underneath were foam “muscle suits” which were colored and patterned specific to the characters – silver for Panther and gold leopard print for Killmonger. Those colors pushed through the thin outer skin of the suits which were silicon – and incredibly delicate. They were prone to damage during the rigorous fight sequences.

The CG versions of the suits had to feel similar to the real thing. The suits eventually evolved during post, requiring full suit replacement for all shots. But the practical suits were the baseline. Marvel sent the suits to Method for the modelers and texture artists to work with the material directly, and glean detail that may have been missed with texture and reference photography. This was critical since the suits were so complex.

Suits were modeled from photogrammetry booth scans of Boseman and Jordan by Henry Jung. These were the “actor” versions of the suits, which were needed during suit transformations and when the masks were retracted. Because it was imperative to match the neckline, we opted for the actors’ real proportions. We also had a “hero” suit, which was used for the majority of the work. The hero suits have more superhero proportions – smaller head, broader shoulders, thinner waist, larger thighs. You know – a super hero. This was used to replace Black Panther or Killmonger for fighting scenes, stunt work, etc.

The suits were injected with a ton of AOVs within the shaders for the most control in comp. All of the patterns, glyphs, scars, etc., were accessible in different channels in Nuke. This way, the CG could be dialed in to more closely match the plate photography, or to add some artistic changes like boosting up Killmonger’s leopard print. The AOVs also drove the FX for when a suit was charged up with kinetic energy. Lookdev for the suits was done in VRay by Casey Rolseth, and in Mantra by James Stuart. Texturing for Black Panther was created by Eric Zhang, and Killmonger was Justin Holt.

Beauty renders were done in VRay while FX passes were created in Mantra in Houdini.

The scene in the lab where we first see the formation of Black Panther’s new suit was driven by a Houdini procedural system, which would also be used in the CIA Blacksite and for when Killmonger faces off against the Dora Milaje. These transformation shots were lit by Jean Choi, and comped by Louis Corr, Stefen Richter, and Heidi Harnish.

How did you handle their rigging and animation?

Rigging was accomplished with blend shapes and deformations for correctives rather than a skinsliding/simulation/muscle system. It was decided early on that that suits wrap around the wearer and compress things into a tight superhero suit. So there isn’t much extra movement happening.

On set co-animation supervisor Daryl Sawchuk and associate VFX supervisor Todd Perry arranged for range of motion sessions with principal actors and their stunt counterparts, in their suits, the muscle suits, and bike shorts. Shooting from multiple directions, we were able to provide accurate movement for rotoanimators to get started even while principal photography was going on. The rotomation was provided to the rigging team who could then set up corrective blend shapes that would match the actors.

Animation was a combination of rotomation and full animation – and sometimes both. Rotomation was used to make sure that we were capturing the essence of the actors and the fighting style of each character. Black Panther has more sinuous, cat-like movement. Elegant – like tai chi or kung fu. Killmonger is CIA and military trained, so his style is harder, more square and face-on. The stunt team worked long and hard to develop these styles and choreography, so we tried hard to maintain that.

Sometimes animation would take over if movements needed to be amped up to superhero level, or if a hit needed to be harder or faster. There were also plenty of times that we would replace a Dora or Border Tribesman because the choreography wasn’t clean enough, or telling the right story. Sometimes the story would have changed from when the original photography happened.

Full animation was used for superhuman event: falling into the vibranium mines, people getting blasted by a kinetic burst from a panther suit. And for sure, the rhinos. We had a lot of animators come to our show from OKJA – so there was a lot of recent, built up experience of animating quadrupeds.

Rhino rigging and tech animation was critical. Later in the production it was decided to add armor onto the rhinos, which increased the complexity of the process dramatically. Rhinos each had a full skeleton underneath with an appropriate muscle system. Muscle jiggle and flexing was set up to “fire” based on the animation. A subcutaneous level of fat and tissue was simulated on top of the muscles. Skinsliding simulations were calculated on top of all THAT (surprisingly not as much jiggle as expected – rhinos are seriously muscular). Then armor was simulated. And then they had cloth blankets that matched their owners. Tech animators went in and made correctives to unsure that nothing was interpenetrating. It was rigorous.

Can you tell us more about the shaders and texture work?

Texture was done predominantly in Mari, and shader work in VRay. Some assets had to be developed in both VRay and Mantra depending on how the asset was being used – beauty versus effects. Justin Holt and Eric Zhang headed up the texture dev with nearly the entire team of modelers also taking up UV and texture development for the hundreds of models.

Hero characters were textured using photography from both photo sessions with the costumes on the characters, and then a separate session with just the pieces. Like the Panther outfits, Marvel sent Dora Milaje armor, Border Tribe blankets and other helpful pieces that we shot in our own session after discussion with the asset team on what would be helpful for them.

Shader and lookdev development was worked out in a Maya scene that represented the photogrammetry booth – the array of lights. This way, the assets could be compared 1:1 with the practical versions to ensure photorealism. Environment HDRs from set were also used to see the assets in varying lighting situations. Much of the lookdev work for digi doubles was shared between Casey Rolseth, James Stuart, Ken Bailey. The rhinos where squarely on James Stuart. Props and vehicles were shared between Casey, Jean Choi, Alastair Ferris, Luke Nyugen.

With this dark color, how did you handle the lighting challenge?

Great question. Onset photography was our primary baseline for how the suits should appear. It also gave us cue for key-to-fill ratio, light intensity and direction. But, there are plenty of shots that are almost entirely CG where we don’t have reference. A shot where Black Panther tackles a rhino is one in particular that gave us trouble. If the suit was too black, it wouldn’t match other black values in the shot. If we lifted it then he would go silver or charcoal. It was a fine balance.

How did you approach the big final sequence?

For the final sequence, we knew we had to dial in the environment so that it would hold up no matter what direction we were facing. With upward of 300 shots just in those sequences alone, we knew that we couldn’t custom tailor per angle. However, we did take each direction and found a key shot that would become our touchstone for how things would look in that direction. With over 20 lighters, led by Sergio Pinto and Jon Shaw and 45 compositors, supervised by Aleksandra Sienkiewicz with leads Louis Corr and Mauricio Valderrama, that’s a lot of creative minds working on the same problem. So, once we landed on a look, we would bookmark that shot and guide everyone in that direction. Mauricio was critical in getting his eyes on all these shots for continuity and making them feel like we are in the same world.

What was the most difficult part for this sequence?

The sheer volume of work to put this sequence together was the most daunting factor. But there was also a severe time constraint. This is always the case in visual effects, and has been since the dawn of film. But the faster and more efficient we get, the more is thrown at us to get done in a shorter amount of time. In this particular case, much of the final battle was shot in late October during a reshoot – which only allowed for a couple months to get everything together. We had some tracking and roto work coming to us in late December. Ultimately this time crunch made things difficult – but I can’t say that it was for naught. Everything that was shot was for the benefit of the film. And that speaks for itself.

Can you tell us more about the design and the creation of the various aircrafts?

Method was tasked with building the Dragonflyer and the Talon Fighter aircraft. We used concept designs from Marvel as a starting point and made modifications to add functionality and extra mechanical detail. The Talon fighter had a dual purpose, it’s part F-16 part vibranium cargo transporter. We designed several prototypes to figure out how it should transition and fly whilst carrying a load of weapons.

The Dragon Flyer is designed as a utility aircraft for the mine but it’s also a formidable attack aircraft armed with cymatic weapons. Lookdev referenced stealth fighter jets as well as the practical Dragonflyer cockpit shot in Atlanta.

How did you handle the crowd animations?

Method built 30 digital doubles which all ended up being used in the final battle sequence. There are the Dora Milaje, the Border Tribe (who wore blankets), the Kings Guard, and the Jabari tribe who have white hair all over their armor as well as grass-type skirts.

Each tribe had their own style of fight choreography on set so it was important to use the same stunt fighters from the shoot for the mocap session to maintain consistency. We used Golaem to populate and add battle vignettes into the shots and added cloth/fur sims to the Border Tribe blankets and Jabari costumes.

Can you tell us more about the rhino creation?

The M20 Rhino, W’Kabi’s steed, was modeled by Mayuresh Salunke in ZBrush and Maya. Then fine detail modeling and texture work was accomplished by Tristan Rettich, who had come from the OKJA team.

A hybrid of White Rhino and Black Rhino features were used, and then the size was exaggerated. A lot of time was put into the face around the eyes and the mouth. Rhinos have a LOT of movement going on around those areas, and we were going to be getting extremely close – i.e. a closeup of a rhino licking a character’s face. This model also went to ILM for a few shots in a ranch area around the borders of Wakanda, where W’Kabi’s tribe resides. So even though ILM artists likely rejiggered the model for their own purposes and pipeline, we wanted to make sure they had a base amount of detail around the face.

The two other, smaller rhinos – affectionately named Alan and Steve – were derived from the M20, scaled down, textures and shaders adjusted, and then given unique horn configuration. Like shapes of an Orca dorsal, the horns provide personality and identification.

Unique armor was concepted out for each rhino, going through tons of creative cycles to ensure that we were staying with the Afrofuturistic sensibilities that Hannah Beachler had instilled into the rest of the film. We needed to make sure that we strayed away from Eurocentric armor or Asiacentric. Wakanda is untouched by colonialism, so design and function had to evolve without those influences.

How did you animate them?

Animation for the rhinos came from our animators well-versed in movement of quadrupeds. Most of them had tons of experience from OKJA. We gathered lots and lots of footage of rhinos doing things – galloping, charging, spinning, chewing, standing with ears fluttering. Animators used that to build a library of actions. Animators began working on run cycles as soon as we had a model with the correct proportions. We also requested plates early on, even without an edit that was close to locked. The previz/postviz was a collection of quickly blocked out sequences that really had no foundation in the speed or gait of a real rhino. So animation supervisors Daryl Sawchuk and Matt Kowaliszyn pushed to get the shots early so that the animators could contribute to bits of rhino actions that could help inform editorial for timing and such. The team leads Jye Skinn and Soumitra Gokhale, and rotoanim lead Josh Samuels, made sure the vast amount of animation got pushed through.

The final sequence has many FX such as laser, beams, shields and explosions. How did you create these elements?

All of the effects for primarily driven by sound cymatic frequency patterns. That is part of the vibranium mythos, so all the technology started from this point.

Spear blasts and Shuri’s gauntlets (which we dubbed “kitten mittens”) have an initial blast, and then a residual noise pattern with the cymatic signature in them. Shuri’s kitten mittens also have a different setting that she uses to try and subdue Killmonger. Those have a pulse through them – almost like a subwoofer. The effect covers Killmonger and dissipates into smaller cymatics.

Nakia’s rings have a cymatic energy that holds the outer ring and the inner ring together.

The shields form from the Border Tribe blankets – lightly tethered to the vibranium patterns sewn into the blankets. They needed to have transparency, but also needed to feel thick and substantial. A honeycomb pattern weaves through the shields – reflecting patterns found throughout the film. The edges of the shields are partly inspired by Kylo Ren’s lightsaber – a crackling, aggressive energy that no one would want to touch.

Dragonflier blasts are derivative from Klaue’s sonic arm blast developed over at Luma. They sent over their breakdown, and we replicated for our Dragonfliers in both the battle sequence and when Ross is remote piloting the Royal Talon Fighter from Shuri’s lab.

The explosions from the Dragonflier blasts are a combination of a physical explosion – more like an air mortar than an incendiary explosion. A displacement of earth and dirt. But within the dirt is the residual energy from the dragon blast, illuminating the dirt and dust, but forming into cymatics.

All effects were driven by the FX team in Houdini led by Maciej Benczarski, providing a plethora of AOV control passes for comp to dial in the recipe.

Which sequence or shot was the most complicated to create and why?

The shot of Black Panther and Killmonger fighting as they fall down into the vibranium mine. The shot is quite long with a bunch of animation beats that had to be hit. It also went through many different iterations. Originally, it was short and had us falling down the mine shaft toward the vast expanse of the mine, then cutting to an extremely wide shot inside the mine. That changed. It became a oner that would have the camera falling with them until the impact of Black Panther as he hits one of the tracks. However there were two filmmaking styles at work here. Ryan Coogler liked to have things evolve within a shot – a long, long shot. Marvel liked to be a bit more cut-y. So, we ended up rendering from, and animating to, multiple cameras, so there would be b-roll to cut away to. Ultimately, it would end up remaining a oner.

The environment is a behemoth. There is a lot of geometry, complex shaders, and a vast open space to try and indicate scale and depth. Plus, there are these train tracks criss-crossing all over, which has to have a script that would populate the track geo at rendertime. Otherwise the scene was too heavy for Maya to handle.

Comp had to balance the color of the suits against a dark background. And incorporate the kinetic energy within the suits – but can’t be too much like a Christmas tree. And the look had to match to DNeg’s shots, which we would be cutting directly to.

And the shot was in actual stereo – so both eyes have to be rendered and then comped accordingly.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

TSP: A a long shot of the Royal Talon Fighter and escort ships landing on top of Mount Bashenga at sunset, then the camera dives into the mine shaft and ends up looking through the windows into Shuri’s Lab. Lit by Sergio Pinto and comped by Alison Lake.

AB: I like the reveal of Killmonger for the first time and the fight between him and the Dora Milaje.

What is your best memory on this show?

TSP: Seeing the fan reactions when the first trailer was released.

AB: Working with the Dora Milaje on the pick up shoot, they can fight.

How long have you worked on this show?

TSP: One year – to the week.

AB: 10 months.

What’s the VFX shot count?

406 shots.

What was the size of your team?

Roughly 200 people.

What is your next project?

TSP: Next project is called naptime. I’m taking a breather for a few months to work on my own projects and help other filmmaker friends with their projects.

AB: Can’t say; I signed an NDA.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

TSP: JAWS, STAR WARS, RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY.

AB: BRAZIL, 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, RAGING BULL, BLADE RUNNER.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Method Studios: Dedicated page about BLACK PANTHER on Method Studios website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2018