Luke DiTommaso has been working at Molecule VFX for over 16 years. He has worked on many shows such as The Giver, Zoolander 2, The Purge and The Plot Against America.

What is your background?

I’m a Brooklyn native who wanted to be a cartoon growing up and became a visual effects artist as an adult. I started as a compositor and got my first big break on Rescue Me, a post 9/11 TV series about firefighters in New York. I learned the ropes of on set supervision through the prism of how I would like to receive the footage as compositor. Often I would also comp the shots I supervised. Over 200 credits, later I ended up on Bliss.

How did you and Molecule VFX get involved on this series?

One of the shows I worked on along the way was a series called The Path. The pilot was directed by Mike Cahill. He and I are exactly the same age, his enthusiasm is infectious, and we just clicked together on a personal level. When I found out he was directing Bliss, I reached out to him. We also knew the Post Producer, Isabel Henderson, from several past projects. So it was a friendly and comfortable fit for everyone. Bliss had a wonderful and talented VFX Supervisor, Michael Glen, who did all the prep and on-set supervision. He gave me and my team a really tasteful direction throughout the post production process and actually did some of the shots himself right at our facility alongside the artists.

How was the collaboration with Director Mike Cahill?

Mike is a Renaissance man. He not only wrote and directed the project, but he was very hands-on in every aspect of the film from the production design, editing, storyboards for animation, he even did some of the temp comps. Oftentimes, I have to translate a director’s notes to a specific action list for my artists. But Mike speaks VFX and his notes are crystal clear to everyone on the team. He’s also incredibly effusive with his praise when we nail something, which inspires everyone. He’s a very effective leader.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

There were some things that Cahill and Glen had already worked out, like the Brain Box and the Hologram people. This was communicated to us very clearly and there was little exploration required, mostly fine tuning. There were other things like the World Blending that required more of a collaboration. When Mike knows what he wants, it’s easy because he knows how to tell us. When Mike isn’t sure what he wants, it’s also easy because he trusts us to present him options and knows how to guide us from there. I think his expectations were for us to mirror his enthusiasm and engage as creative partners.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Our producer, Michael Fernandes, did a fantastic job keeping the train on the rails. He not only managed the artist resources and communicated with Post, but he gave really good creative input on shots. Fernandes is very detail oriented, which suits him well on his traditional role of budgets and schedules, but he also has a keen eye for details within a given shot. I knew that by the time he presented something to me that it was truly ready for creative review, which was a huge benefit to me and the show overall. We organized shots by category, primarily for consistency. So for instance, we had a Holograms team, a World Blending team, a Brain Box team, a Van team, etc. Of course there was some overlap, but this allowed us to be efficient internally, especially when reviewing a series of shots within a sequence.

How was split the work amongst the The Molecule offices?

We did the show entirely in NY. Interestingly, we did half the show in our Studio facility and finished it remotely, due to the pandemic.

Our heroes have powers in this reality. How did you work with the SFX and stunt teams about that?

I have to give Michael Glen credit here. He planned and supervised the SFX wire work for the roller skating scene, the puppeteered robot chef arm, the explosions during the world blending, etc. He did a fantastic job on set and came back with some excellent plates.

Can you tell us more about the smashing of the van?

This was a fun sequence. We had a few ideas about how to execute it, we thought about doing some kind of transition from the real van to the practically smashed van that they shot. In the end we replaced the entire van in CG to keep it all seamless. We modeled, textured, lit, and animated it in Maya and did the simulation of the crushing in Houdini. We had a couple separate passes for shattering glass and steam that we also did in Houdini. I’m so proud of how our CG team brought this all together. Obviously Comp did some nice sweetening to tie it into the footage convincingly, but our CG team were the heroes on this.

How did you create the various environments?

The Production Design and locations were pretty brilliant. We did some Matte Painting.

Can you elaborate about the creation of the various impossible camera moves?

Early in the film, there is a great shot from the interior of an office that flies through the window and out to a wide shot of the exterior office building. That was shot with a steadicam at the stage, walking through a cut out in the wall and a drone at the location, We had to 3D track both shots, and essentially blend the two tracks where they overlapped to create a hybrid camera move that spanned both takes. We did have to completely rebuild the interior of the office in 3d space when the drone flies outside to make the transition work.

Can you explain in detail about the “ghost” characters creation?

The “Ghosts” or the telepresence effect in the second act of the film had to be world defining as an everyday mundane tool in their society, like smart phones are to us. When Cahill described that the entities should feel like something that takes up physical space, we recognized the need to avoid the typical look of a hologram broadcast (for example, Princess Leia) and instead, the holograms would take on prismatic light bending properties. This would also mean that the ghosts would take on the lighting as well as the shadows of the world around them. With that in mind, we landed on a look that was not entirely additive and the holograms would emit chromatic aberrations and distortions of their own, like looking at refractions inside a jewel. Achieving this look required many hours of rooting of the target person to be “ghosted” then painting the background and sometimes people behind them. We made extensive usage of Mocha tracking and sometimes Camera Tracking in Nuke and Syntheyes for all the painted clean plates to be accurately occupying the space behind the ghosts.

Later in the movie, the two realities are mixing up. Can you explain in detail about its creation?

The World Blending scene was approached as a sort of invasion of reality. We took the previous ghost effect and added the idea that they were now phasing into real solid objects. As our two heroes run through chaos, the objects and people now that were becoming “real” would pose a real danger of colliding into them. Timing was important and we went through many variations of speed and cadence of the objects appearing. There was one shot of a man with a molotov cocktail running towards the camera that we used as our hero shot. Eventually we landed on the concept of making it look like he was running through a membrane from his world into this world. That really resonated with Cahill so we built upon that. We added some glitches and brought it to final. That became the template for other shots. Some of these shots had over 50 grouped objects animated at various speeds to make the effect work. This was by far the most challenging scene in the film as there were many moving parts and objects and they all required precise timing and painted clean plates for all.

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

The Van crushing was probably the most technically challenging. There were lots of moving parts and hand-offs there within the CG department. Renders were a bit of a bear so revisions were not super quick. But ultimately we knew what we were going for so it was basically a straight line to get there, albeit slow and tricky. World Blending was the most challenging creatively, because we needed to create the look, which evolved over time. So there was a bit more zig zagging to land on the final effect.

Did you want to reveal any other invisible effects?

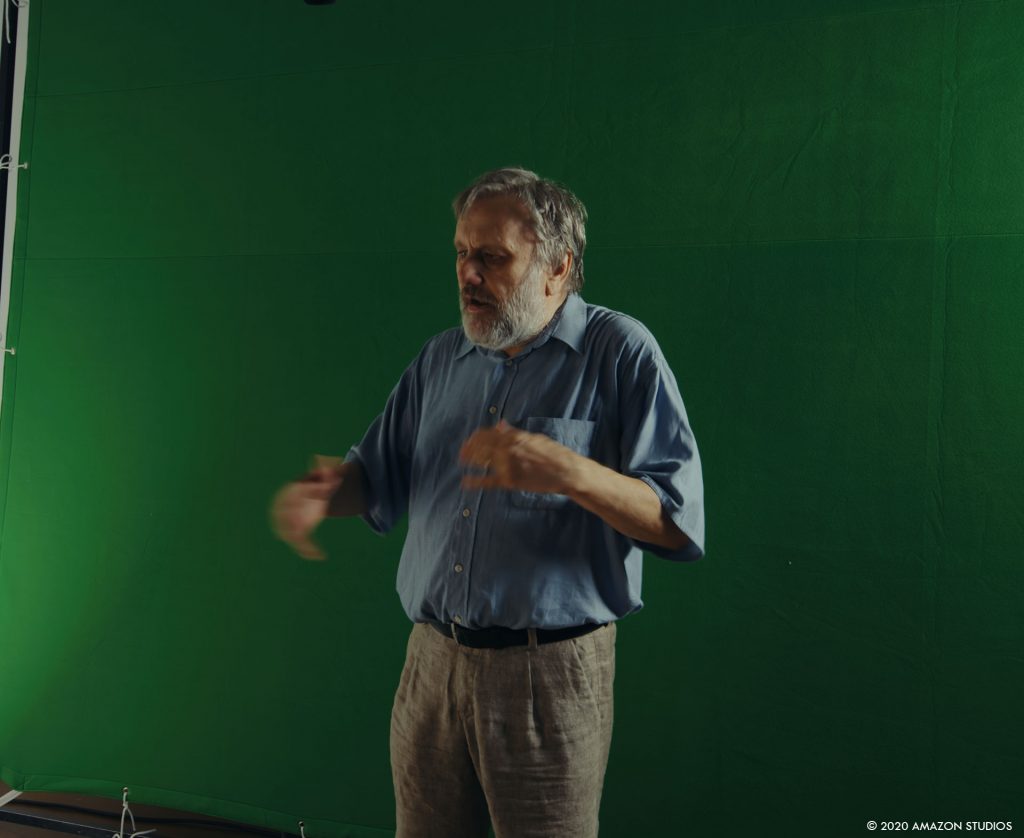

At the end of the film, Owen Wison’s character reconnects with his daughter who was waiting for him at a park bench. That whole scene was shot on greenscreen but I think you would be hard pressed to tell that wasn’t shot on location. The plates and the comps were really on point.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

I think it went quite well overall. We did spend more time detailing out the specifics of the liquid that the brains floated in then the brains itself.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

There’s one shot of a robot Chef arm pouring honey on a dessert that is not even the most technically impressive or complex shot, but it’s such a nice blend of SFX and VFX design. The result is really understated and elegant, and I think so convincing that it just sails by, like of course there’s a real robot arm there, makes perfect sense.

What is your best memory on this show?

This was one the last projects we worked on in our facility before going remote, so I have really fond memories of doing dailies for Bliss in the screening room with the whole team.

How long have you worked on this show?

We worked on this show for around 6 months.

What’s the VFX shots count?

There were a little over 200 VFX shots. Some of them were fairly simple but a large percentage of the shot count was fairly complex.

What was the size of your team?

There were 36 of us working on Bliss. We had our Comp Supe, John Sung leading a team of 24 Compositors. We had our CG Supe, CJ Chun leading 4 CG artists. There was our Matte Painter Jina Lee, and three support people for me, Michael Fernandes, and my partner Andrew Bly. We all worked in concert with Michael Glen.

What is your next project?

I’m currently wrapping up post a period drama Genius: Aretha on Nat Geo, and I’m on set for an action show, The Equalizer which just premiered on CBS after the SuperBowl. Next for me will be S2 of Starz’ breakout hit P-Valley.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

These might not be the most unique deep cuts, but I would say that as a kid, Star Wars was a film that captivated me and pulled me deep into that universe. I remember seeing Batteries Not Included in the theater and having a really emotional reaction to these little flying alien robots. As I got a little older, The Godfather felt so grand in scope and drama, like a stylized world that I could inhabit. When I was in college at SVA studying Computer Art, The Matrix was a film that really gave me a red pill on the power of VFX to tell a story.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Molecule VFX: Official website of Molecule VFX.

Amazon Prime Video: You can watch Bliss on Amazon Prime Video now.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2021