After several years at Zoic Studios as a TD and engineer, Justin Ball joined the team at Brainstorm Digital. He participated in many projects such as BURN AFTER READING, DUPLICITY or THE ROAD. It also oversees the effects of several films like BROOKLYN’S FINEST, or LETTERS TO JULIET and THE ADJUSTMENT BUREAU.

What is your background?

I studied sculpture, animation, and programming at Pratt Institute in New York. I had my first real exposure to CG and VFX while working at Curious Pictures in New York, in the model shop, building the last of the handmade puppets for their stop-motion kids’ show on HBO, A LITTLE CURIOUS. It was there that I experienced firsthand the industry’s real push to go digital. After teaching animation at another NYC university while finishing my undergrad at Pratt, I moved to L.A. and started working for the then-start-up, Zoic Studios. I functioned mainly as an engineer

and TD there, working side by side with amazing artists, supervisors and creative directors who really gave me a passion for the industry and the work that we do. Eventually, I changed roles at Zoic and got more into effects. Soon after that, I moved back to New York to help build Brainstorm Digital, a new all-film VFX house in Brooklyn.

Over my years at Brainstorm, I rose from being an engineer/TD to an effects artist to my current position as VFX Supervisor. I come from a very technical background, but have also always had the passion for the creative. VFX Supervisor is a great mix of disciplines. You get to work and design really creative shots, and then figure out how in the world you will make them work, both on set and back in the office. It really requires many skill sets.

How was your collaboration with the various directors of the series and especially with Martin Scorsese?

It was very interesting to work with all the directors. It was a first for me to have that many different creative ideas and approaches centered around a single project, giving every episode a totally unique feel. The biggest challenge was the informational gap in dealing with the complex filming location of the boardwalk set. So there was a lot of work and discussion every episode with the new directors to bring them up to speed as quickly as possible on the difficulties of the location. One of the nice things was that we had alternating DP’s for each episode, and over the course of the season they became well-versed with the shortcomings of filling in the big blue box. After the initial ramp-up period at the beginning of the season, it became a well-oiled machine.

Working with Scorsese was fascinating. We weren’t able to spend much time with him due to how busy and in demand he is. But I must say it was a huge pleasure to both watch him work and to work with him. He was a tremendous asset for us, as we would approach him with options and he could be extremely decisive about the approach and direction he wanted to go. So the lack of one on one interaction was more than compensated by the precise amount of direction and information we were provided.

|

|

Can you explain how Brainstorm Digital got involved in this project?

In late 2008, we were approached by a producer friend who was attached to the project. Back then, it was just a loose idea and everyone was trying to figure out how to pull it off. One of the key elements up for discussion was how and where to film a 1920’s Atlantic City. Initially, there was an overwhelming push to try to film the project on a sound stage, which was a big “no-no” for us. The feeling was that even though we could manage to do the filming inside, and certain issues would be lessened by filming in a controlled environment, the show would never feel as if it were taking place on an actual, outdoor, seaside boardwalk. So for the first meeting with Executive Producer Eugene Kelly, we put together a rough projection test with some sky and water plates we filmed, to help illustrate how VFX could help the show and more importantly, how much set would have to be built.

We started by going out to Brighton Beach in Brooklyn to film some open coastline with recessed buildings. We took our HD camera and played with some camera moves on the beach. We then took that back to the office and built a 3D camera from the data we’d collected. Then, using archival photographs provided by the production historical researcher, we started to formulate a plan. One of the difficult issues was at that point in time we did not have an overview image of what the whole Atlantic City boardwalk looked like back then. I spent a long time studying antique photographs to find images that overlapped and structures that were geographically located on the boardwalk. We centered our test around the Blenheim Hotel because it was the most visually interesting structure located on the boardwalk in 1920. The original Atlantic City boardwalk was a constantly evolving attraction; from year to year the entire place changed dramatically. Buildings were torn down, and others were erected in their place, with even more floors and levels added to already existing buildings. Finding a way to recreate a realistic period set from the old, dynamic boardwalk was an interesting challenge.

After deciding a geographic location to base the test, we built a loose projection system in Nuke. Using black-and-white photographs, we built a portion of the boardwalk set to make the test. With our initial test, we were forecasting that production would only need to build about 160 feet of set before VFX could take over. The issue with that was that it limited the filming options for the series. So eventually we all decided to extend the set another 100 feet to around 270 feet.

|

|

What references did you have for the streets and the pier of Atlantic City?

Production had hired a researcher, Edward McGinty, to help research all aspects of the show. Either the production VFX Supervisor, David Taritero, or Ed would track down any imagery or ref we would need if we could not find it ourselves. This was such an amazing asset for us to have in helping develop the realistic vintage look for the show. We also worked very closely with Robert Stromberg, who was a matte painter and VFX Designer for the series.

|

|

Were you involved in pre-production in order to help the shooting? Did you create some previzualisations for this?

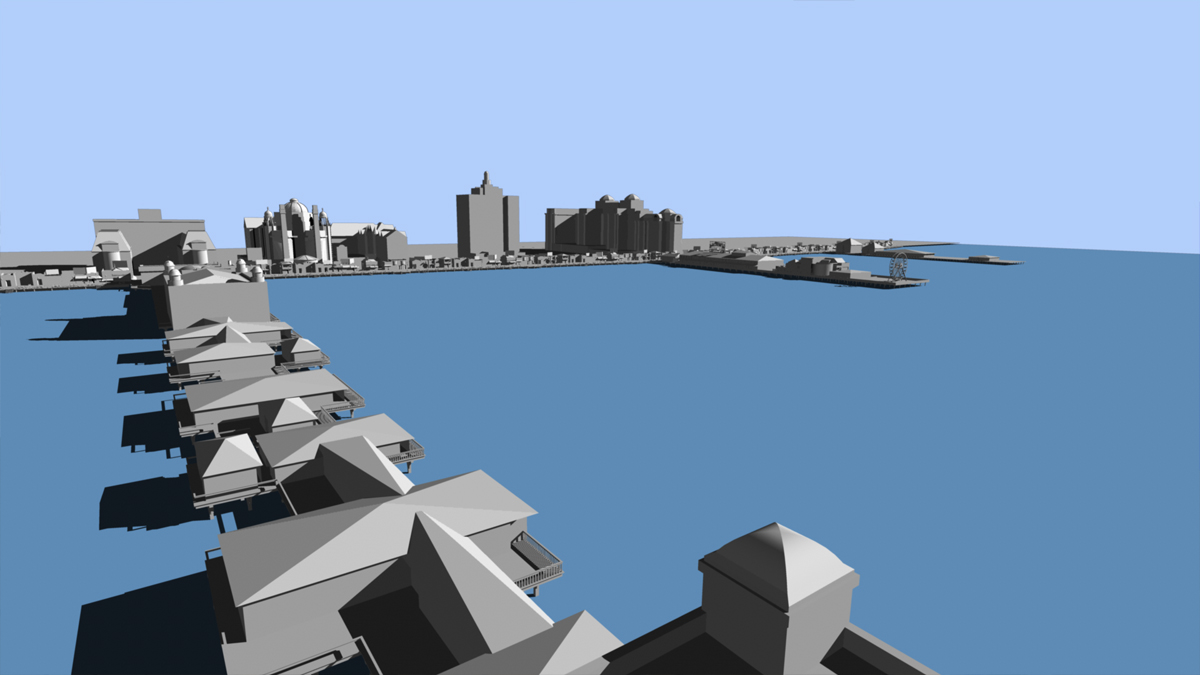

Yes. We were heavily involved with every aspect of the design and building of the set. From helping to pick the location, to previzing the set, to designing the backlot, we were there all the way through filming. It started early on from that first meeting with the Art Department. We hired an art director from the HBO team to build us a scale 3D model of the set as the Art Department was designing it. Even though we were usually about a week behind the Art Department, we always had a scale 3D model in Google Sketch-Up. And while the Art Department was working on the details, we would work on the world beyond the set, both the placement of period buildings and also the practical elements surrounding the present day set. We used this model to help us visualize the layout of the bluescreen and how to design the space of the backlot.

The bluescreen in itself was a difficult challenge to take on, because we were not sure how best to rig something that large. We went through many different ideas about how to make it work. We had thought about cloth draping systems all rigged on wires, or systems with traveling 40×40 bluescreens, but knew that those could not cover the scope of the set that we were building. A bad bluescreen setup could lead to problems while shooting with lengthy re-set times, and on an episodic shoot, this was not really an option. We also needed something that could stand up to a New York winter, a huge challenge in itself. We were in constant contact with David Taritero, who was going to be the production VFX Supervisor for the show, but was still in L.A. finishing up post on HBO’s THE PACIFIC while all of this was going on. Fortunately, we were able to share ideas with him while going though the design stage. Dave had used a similar curtain system on THE PACIFIC and was able to give us a firsthand account of the pluses and minuses of that approach.

While researching this issue, I came across an article about the movie CHANGELING, where they mentioned that they used a shipping container as a green backstop for their backlot because it was a cheap but solid structure. When I read this I thought it was the perfect solution to our problem. We proposed this to production, and after we convinced them that the containers would also provide storage on a backlot that had very limited working space, they agreed. A secondary benefit of building a huge wall out of shipping containers was that it provided visual protection of the set from onlookers, along with weather protection. The set was built in an empty lot in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, right at the edge of the East River. Without that protection, the winter would have been much harder on both the filming schedules and the actors, not to mention the complications that can arise from curious crowds.

Using the 3D model, we were able to lay out the placement of the containers within the physical space of the backlot. We were also able to map out the number of containers to use along with seeing what they would look like in that environment. Since we built the set in real-world scale, I could plant a camera on the elevated production set and I could see what we would see once the set was built. This let us map out how high the wall needed to be to cover certain elements that we did not have control over, such as buildings across the street and even the Chrysler Building across the river. We were also able to test camera heights and lenses to know ahead of time when an actor’s height would break the coverage of the blue wall, revealing the real sky behind them.

This setup was extremely useful for the DP’s to get an understanding of the working conditions of the boardwalk even before it was built. We spent multiple days with Stuart Dryburgh, the DP for the pilot, working on angles and shots before the set was even complete.

|

|

About the shooting, were you able to shoot all you need in front of a bluescreen or did you need some extensive roto?

We were able to have quite a few production days in front of the bluescreen to film actors and background to get different elements. One of the issues we had was that the show takes place over the course of a year, so the people elements that we filmed early in the season would only work for a portion of the episodes. There were also many different types of attire and day and night scenes where we needed to fill people in. For the most part we were able to get all of this covered to a usable extent. But for some of the beach scenes, we weren’t able to get everything we needed due to camera moves in the original plate and weather problems at the beach. So in a few shots we did have to get into roto extractions to help cover the camera moves.

|

|

Can you explain to us in detail how you recreate entire streets and the pier?

The approach we took for these shots was that we would use matte paintings and projection setups in Nuke wherever we could get away with them. Initially, David and the production team and I discussed building the entire boardwalk area in 3D, as it was a finite space and we could build it as an easily reusable asset for years to come. But when first embarking on this project, none of us could know how much or how little we would see beyond the practical set, so we opted to do more paintings in the beginning. And when you have access to the talent of Rob Stromberg for your paintings, that’s a very easy decision. But over the course of the season we started to pick out more and more “featured” structures that became 3D models and independent assets.

Knowing the limitations of time and resources for this project, I wanted to use Nuke whenever we could to get the most out of our 2D team as possible. We relied heavily on 3D camera tracks and projection geometry to build a large part of the world seen in BOARDWALK EMPIRE.

In Episode One, we see a beautiful panning shot on Sewell Avenue, this street with old 1920’s beach bungalows that still exists out in Rockaway, Brooklyn. The problem was that only one side of the street actually had the appropriate houses. On the day of filming, I shot images of every house that was dressed for filming from every angle I could get. We used these images as well as still frames from the plate footage to re-project the surface back onto 3D-modeled houses. The houses were built very loosely in Maya and then brought into Nuke’s working space. We surfaced all the buildings in Nuke except when we needed some shadow casting passes. We would then kick that back to 3D for a good shadow pass. We also rebuilt the electric lines and poles in Nuke along with the ground plane and full sky replacement.

|

|

As for the boardwalk shots, depending on the camera move we used different techniques, but it was along the same lines as what we did for the street. We had the pre-viz model we built to scale in pre-production as a starting point, which gave us a lot to work with. That model was converted to Maya from Sketch-Up into a few different resolution levels. Then I would use the low res version on-set with my laptop to build camera moves on the fly for the directors, and back in the shop we used it for projection or, depending on the detail, for 3D renders. We also used this model with our 3D tracking team. So every shot on the boardwalk that went into 3D tracking lived exactly where it was filmed on the real set. We could turn over grey shaded renders to the matte painting team, placed with the proper perspective and vanishing points already mapped out. It really helped our build time in terms of the painting portion of the process. We would also pre-light the grey shaded models so the renders could almost serve as an underpainting. The water was just filmed water plates that were tiled out and placed on cards in Nuke.

|

|

In both types of shots, the real feat was to use the strengths and size of our 2D team and to not overwhelm our 3D crew. Using projection setups the way that we did really let our 3D guys operate in more of a supporting role and let the 2D shoulder the mass of shots, so we would not be stuck behind rendering bottlenecks from the 3D side.

|

|

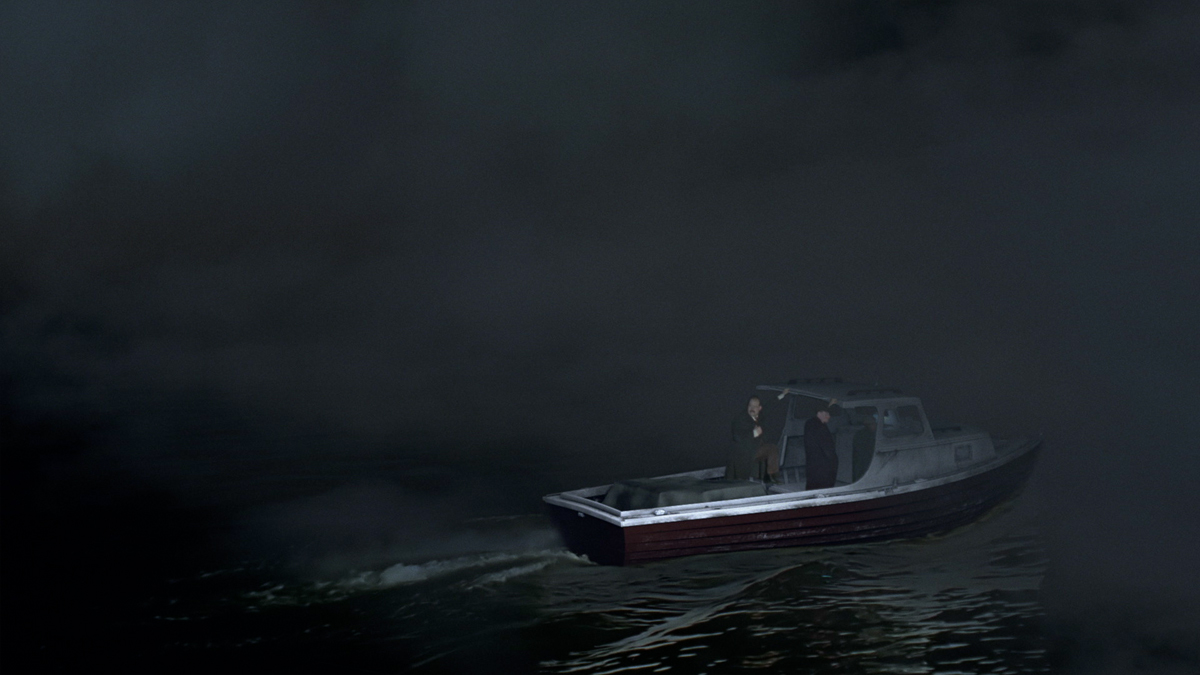

Were you involved on the sequences on the ocean including the shots in which a character is thrown into the water?

Yes, and this is a bit of a funny story. All the shots with the smuggler boat were set to be a VFX split day to shoot both the “dumping the body” shots and the opening shot of the show, where the boat is moving away towards Atlantic City at night. When we were riding to the set that day, Richard Friedlander, Brainstorm’s VFX producer, got a call that the hero boat was taking on water on its way to the set. When we all arrived to the set we assessed the situation there were really only two options: either we would have to shut down and postpone the filming day till the boat could be properly fixed, or we could fix it in post. Robert Stromberg, the production VFX Supervisor for the pilot, pulled me aside and asked how I felt about doing a boat replacement. This was something that neither Brainstorm nor I had done before, but I was very confident that we could do it. So we had the boat team pull up all the boats that were similar in length to the hero boat until we found one that could work for our purposes. It was the approximate length (just a few feet shorter), and it had low enough rails on the side that we would not have any obscuring issues with the actors.

|

|

As this was an all-VFX shoot day we had a lot of opportunities to shoot safety plates to help us with the final assembly of the shots. We began by shooting the actors performing the actions in the stand-in boat out on the water, as we had planned to do with the hero boat. When we heard the news about our our hero boat, we requested that it be brought over on a trailer so that we could get the measurements and reference images for the CG replacement. When it arrived, we hatched another plan. We would also reenact the water scene on the drydocked hero boat.

Now keep in mind that we had planned to do all of our shooting that day from a 50-foot Techno-crane. So we set the camera up on the crane and were able to swing it around into many different positions and angles without ever having to move the base. That saved us a huge amount of time between set-ups on a day that was quickly becoming a mad scramble, all because of one leaky boat. Filming from the crane-mounted camera, we performed the body toss on the drydock boat from many different angles with stunt actors and landing pads. While we were waiting between setups, we would swing the crane over the water and film matching water plates for the angle. We used a tugboat in the water hitting the throttle to create churning water for the plates.

In the end it was up to the director to put the scene together the way he liked. When we received the working edit, we saw the issues we were up against. Some of our shots were re-envisioned in the edit, but luckily with all the coverage we shot that day, we had the pieces to put it together.

The boat replacement shots did have some interesting complications to them. We modeled the boat from measurements and photographic reference. Once we had the boat modeled and matched-moved to the production plate, we found that the difference in scales of the boat was much more apparent than we expected to see. In certain instances we had to do scaling adjustments to help it sit better into the plate. We also found that the position of the cockpit and some other key features on the boat were not really in the exact location, so it took some clever work on the part of our 2D and 3D teams make everything feel right. In certain instances we did have to do some rebuilding of the actors to help sell the effect.

The other issue we had with the boat was the water interaction. I had hoped that we could steal more interaction from the plate, but since the hero boat had a white hull, and was shorter than the replacement boat, we had to resort to some help from 3D. We used Houdini to both enhance the boat and water leading edge interaction along with enhance the splash when man was thrown overboard. The end results are great, but it took some quick thinking to make it happen.

|

|

Can you explain how you created the impressive war wound on the face of one of the characters?

When this topic came up in pre-production, we were worried that the effect would be too big and complicated for us to pull off on an episodic show. The scarring on the face of Richard Harrow was not to be a superficial wound, but rather something that had taken away part of his face. Dave Taritero and I came up with an initial plan for the face shots: make everything as simple as possible. No camera moves, no talking, just a straight reveal. This is how we approached the shots in Episode Seven when we first meet Richard. The idea was to cut down on any of the complex roto work or carving into his face to make the deformation look real.

The shots we did for Episode Ten, where Richard is in the living room on the couch, featured rapid movement, a moving camera, and lots of talking—not simple at all! But since we had already revealed Richard, there was no turning back. For the Episode Seven shot we had resorted to a bit of trickery, with a loose face model, matchmove, and re-projecting the face in Nuke. We pushed that shot about as far as we could go with our sort of mishmash 2.5D approach, and it worked nicely. But for the Episode Ten shots, we knew we would have to be very creative and really get our hands dirty.

|

|

When looking at how to complete this series of shots, I came up with a different approach. Matchmoving a head is a pretty simple thing to do, especially for just a handful of shots, and all we really needed was registration of the wound as we would be taking over all of that portion of the face. We enlisted the help of an old modeling buddy of mine, Brian Freisinger, and a character animator, Anton Dawson, to rig and deform the face to match sync. I took photos of the actor’s face from every angle I could and sent that info to Brian, who built us a pretty perfect face match.

Once again, the production team provided us with all the research we needed, and what we learned was fairly horrifying. We had great examples of the scarring and skin grafts, burns, and all sorts of other trauma that these men had to live with after World War I, and how they used actual tin masks to cover their deformities. We went through a rather long design cycle for the look for the face for these shots. It took us a while to figure out the type of deformity he had and how it would react with his face. The placement of the wound did provide a challenge, as the actor still had the front and rear of his jawbone intact, but a gaping hole in his face and a missing eye. Making the wound look ghastly enough without overdoing it was a bit of a balancing act.

Ultimately, the Episode Ten shots were rendered out of Maya using mental ray and comped in Nuke. One way we helped our compositors was to provide them with a UV map of the face so that they could apply grades and corrections to specific spots, to keep the shot from going back to 3D once the animation and lighting were locked.

|

|

What was the biggest challenge on this project?

I think the biggest challenge on this project was twofold: dealing with the sheer amount of data constantly coming in, and managing the shooting schedule at the same time. We were in post on the show while a large portion of the series was still filming. So we were working on shots as they were filmed, planning new shots, reading scripts, filming elements, and then also working on set with David and the directors to help visualize and realize the world we were creating. It was intense.

Was there a shot that prevented you from sleeping?

Yes–the Episode Two Times Square shot, definitely. It was a total unknown. It was Brainstorm’s first fully CG shot, and it had to be a photorealistic recreation of 1920’s Times Square. You might be amazed by the lack of imagery available of Times Square in 1920, especially from a high-angle camera position. It really just doesn’t exist.

We added a lot of little details to help sell the feeling of Times Square, with endless revisions and much tinkering to make it work.

What is your pipeline and your softwares at Brainstorm Digital?

We primarily used Nuke as our compositing package (but Shake still makes an appearance every now and again), and Maya for 3D. We also use Houdini for the snow and splash effects.

How long have you worked on this series?

We have been on the project for close to 22 months, from the original pitch all the way to the completion of Season One.

What did you keep from this experience?

This project was an amazing opportunity to work with some of the best talents in the field of film and television today. Working hand-in-hand with the writers and directors from THE SOPRANOS and THE PACIFIC, along with multiple Oscar winning directors and artists, was an amazing experience for me. Few other projects will pull that many different talents from all over our industry into one place.

What is your next project?

The project we just finished together is THE DILEMMA for Ron Howard, and we’re in prep mode for Season Two of BOARDWALK EMPIRE.

What are the 4 movies that gave you the passion of cinema?

This is tough–there are so many.

JURASSIC PARK (The film that really pushed me down the path of VFX)

THE SHINING

2001

BRAZIL

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Brainstorm Digital: Official website of Brainstorm Digital.

– fxguide: Article about BOARDWALK EMPIRE on fxguide.

// BOARDWALK EMPIRE Season One – BRAINSTORM DIGITAL – VFX BREAKDOWN

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2011

Thank you! Very informative! I love the before and after shots! Every of your article should be full of that!

Amazing job!

It is very impressive what we the audience do not see in a movie & has a great talented effort behind scenes to make it real.

Congratulations Vincent, the interview is very well explained and detailed. (Love too the pics before & after, talk for it self).

Justin keep the good job!

I had no idea how much work went into making those backgrounds! It looks so real I just assumed it was all an actual set. Awesome work, Justin! I can’t wait to see how your next projects turn out.

Amazing work Vincent.

In epsiode 20 of Boardwalk Empire Nucky is driven to the Atlantic City Armory, which is a distinctinctive fort/castle like building.

The building is the same one used in Sergio Leone’s epic gangster movie Once Upon A Tme In America where Noodles is taken to a Reformatory/Prison.

It look as though some CGI has been used on the roof and entrance. I would love to know where this building is. Can’t seem to find it in the Brooklyn/Rockaway areas.