Adam Rowland works in visual effects for over 8 years. He has participated in many TV series like DR WHO or GENERATION KILLS and also on several movies such as PRINCE OF PERSIA: THE SANDS OF TIME, 28 WEEKS LATER or SKYFALL.

What is your background?

I did a Foundation Art course after school, followed by a BA in Photography, Film and Television. After that I worked in Soho for a bit, running and assisting – mostly TV and commercials, before heading back to college to do the MA in Digital Effects at the NCCA at Bournemouth. I’ve been working pretty solidly, mostly in London, ever since.

How was your collaboration with director Paul Greengrass?

It was a pleasure and felt, as is not always the case, that it actually was a collaboration. He valued our input and allowed us to get on with it, only intervening when he had something particular in mind.

What was his approach about the visual effects?

His approach to film-making, and thus the visual effects, seemed to be all about the faithfulness to the facts and the drama of the story.

He was quite specific about the effect that he was trying to create within a shot or a scene, but was open to our ideas about how this could be achieved. He seemed less interested in how we did things, and more interested in guiding us through why, and what dramatic tension could be extracted from that.

A lot of the time, we would get our first pass at a shot and put it in front of him, not expecting him to final it, but for it to spark a conversation that we could then use to get closer to his vision. Many of our shots went through numerous iterations with what seemed like minute changes between versions, but when you see the final result in the correct context, you appreciate exactly what he was getting at.

What was your role on this project?

I was the Visual Effects Supervisor at Nvizible, and did a fair amount of compositing too.

How was your collaboration with Double Negative VFX Supervisors?

We had very little contact. At the beginning, we were working on a sequence for which they had the majority of the shots, so we had to ensure our comps matched theirs. At that stage we were doing mostly cleanup and sky grades/replacements, so it was important that there was good continuity between the different vendors. Once we acquired our own stand-alone sequences, though, we were pretty much left to get on with it – seeing them only occasionally in the grading suite.

What did Nvizible do on this show?

We were initially brought in to work on a number of cleanup shots and graphical screen inserts, our workload grew exponentially as the project progressed. We worked on sequences that included;

– Environmental cleanup

– Cosmetic augmentation

– Populating empty airfields and aircraft carriers with vehicles and activity

– Rebuilding the environments and camera animation for a skydiving sequence

– An entirely CG seascape

– Animated graphical overlays, sniper-sights, dials and computer screens.

How did you manage the style of shooting of Paul Greengrass?

As Captain Phillips is a real-life story, it was imperative that none of the effects looked artificial and matched seamlessly with Paul Greengrass’s documentary style. Tracking was a huge task, as pretty much everything is shot handheld. For practical reasons a lot of the sequences we worked on were shot day-for-night, this had it’s own implications regarding grade and continuity. We just had to keep looking at everything in sequence and making sure it was all balanced correctly.

The shooting was in multi-format. How did you handle this aspect?

This provided its own set of continuity problems, as we were working on footage shot on 35mm, Alexa, 16mm, Canon 5D, GoPro and others, often within one scene. It was important, therefore, to maintain the inherent idiosyncrasies of each stock during the compositing process. Grain was a big issue, as was lens distortion and aberration, but once we’d established a routine and a process for each camera or stock, it was an easy thing to maintain.

Can you tell us more about your work on-set and then during the post?

We weren’t on set at all, the shoot was supervised by Double Negative’s Charlie Noble. In post we worked with the director, Paul Greengrass and editor, Chris Rouse to achieve their joint vision of how the film should look, and very closely with VFX producer Dan Barrow to get it all done within a reasonable timescale and budget. The majority of the project for us was 2D, although some shots required substantial 3D work.

Can you explain in details about the creation of the various vehicles?

We had a few scenes that involved 3D assets. One required the population of an aircraft carrier with helicopters and personnel. There had been one helicopter onboard, which we removed, but that gave us good reference for the model, colour and lighting. Once it was textured, lit and rendered, the composite was done in Nuke by Moti Biran.

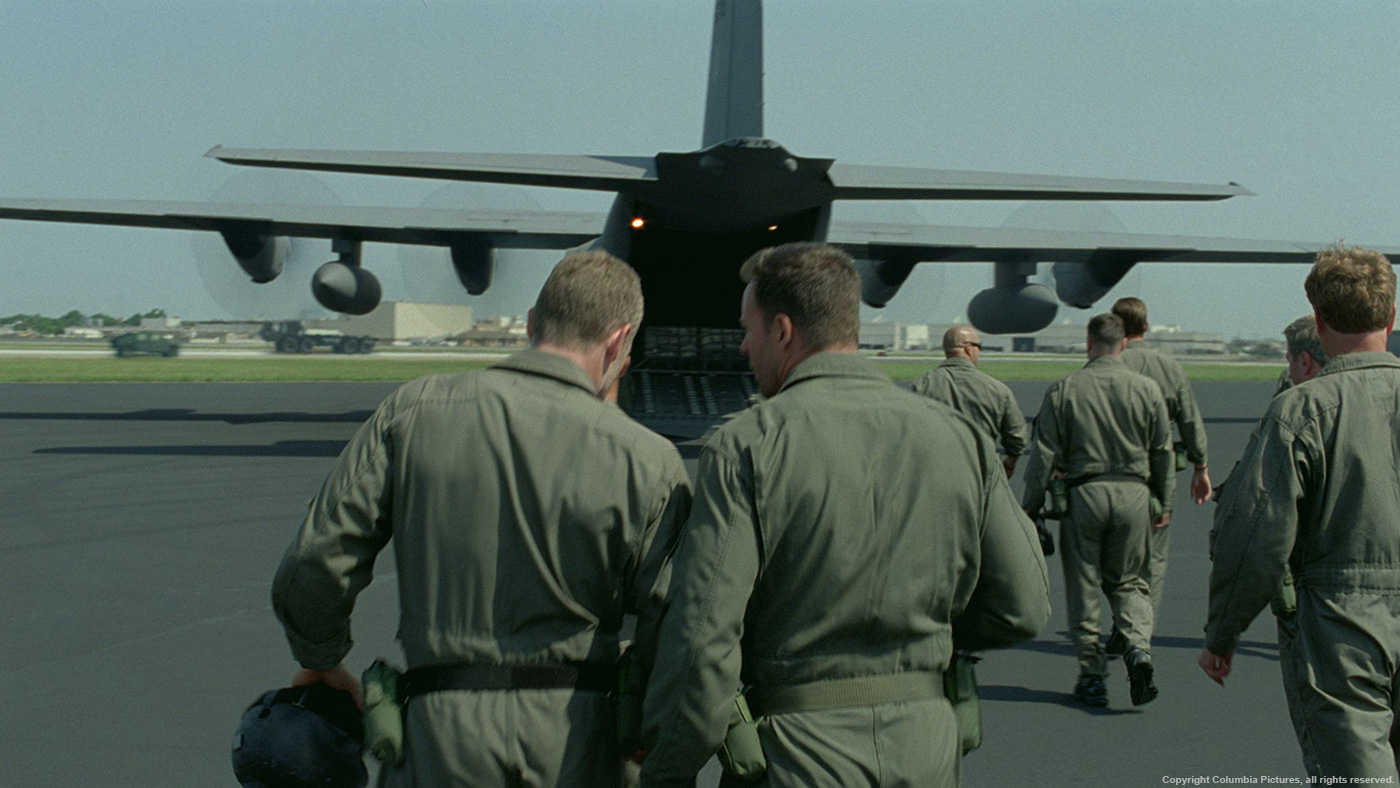

Another sequence, when the Navy Seals are boarding their plane at the airfield, contained a number of CG trucks, helicopters, Humvees and even a Hercules landing.

Because of the director’s preference for handheld camerawork, 3D tracking, animating and lighting this entire sequence could have been very time consuming, but because the vehicles were simply there to populate the background and would always be distant, we were able to use a workaround.

We rendered our previz models on turntables with the lighting parented to the turntable. These elements could then be tracked into the plates in 2D and the compositor could control the perspective shift on the vehicle by simply retiming the animation of the turntable. As they were to be largely distant and out of focus, it wasn’t necessary to use highly detailed textured models. Most of the work, consequently, was done in Nuke by our senior compositor, Gavin Digby.

Did you share assets with the Double Negative teams?

Aside from a sky or two, there wasn’t much that required sharing, as most of sequences did not overlap.

What was your approach about the CG seascape?

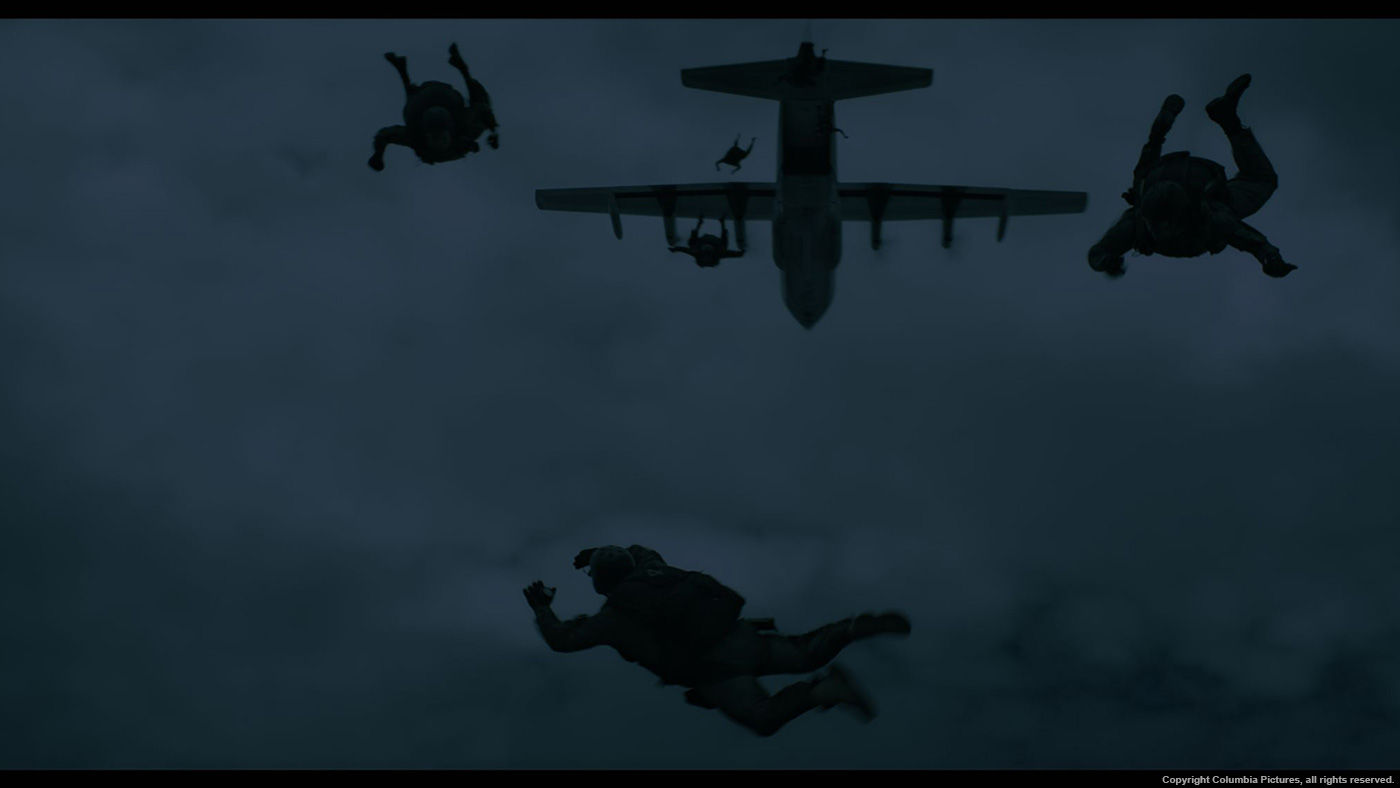

This shot was a particular challenge. Shot with a helmet-mounted GoPro, it shows the POV of a parachutist as he descends into the water. There were a lot of safety boats and camera crew in shot, not to mention the fact that it was shot almost directly into the sun.

The brief was to remove the sun and it’s reflection on the surface of the water, replace the sky, remove the crew boats, add in the military ships, and grade the whole thing to look like night. We decided pretty early on that it would be unfeasible to treat it as a clean-up job. Even with accurate camera tracking and projection, the direction of sunlight meant that patching in areas of sea and getting them to move correctly would be really tricky. The proximity of the camera to the boats and the fact that the sea surface was reflecting the sun meant that the extent of the shot that we would have to replace was huge. It made more sense to do a complete CG rebuild instead.

Can you tell us more about its creation?

The existing shot had been in the cut for some time, and Paul and Chris were used to seeing the sequence with the shots in that as-shot state. There was clearly something visceral and immediate about the raw footage, and it was important that whatever we submitted did not jump out as looking conceptually different from the original, especially as it was cutting to and from other real-world footage.

We had the plate tracked so that we could inherit the exact motion of the original camera and more easily extract any water interaction from the foreground. A sky-dome was painted up, and a reflective CG seascape was created using Maya’s Oceanshader by Sam Churchill. He also did an extra layer of hand animated mid-distant waves and foreground foam to time with the moment of entry. It was all rendered in MentalRay with relatively flat lighting so that it could be easily matched to a convincing night-time colour grade.

All the elements were then composited by Riccardo Gambi in Nuke. He was able to key and roto a lot of the foreground water from the original footage. The GoPro clips its highlights quite severely, so there was a lot of grading work to do to get rid of the remaining reflections of the sun without flattening out the footage too much. He combined this with a number of other filmed elements (foam, splashes, water-on-lens etc.) to create the final effect of the “splashdown”.

What I like about the shot, is that it maintains the same motion and foreground interaction of the original shot footage, but is stripped down and given an entirely new tonal palette. Within the context of the sequence, it’s not something you really even question.

How did you create the other environments on this show?

Within the same skydiving sequence, we did quite a lot of environment work. Most of these were shot with head-mounted GoPro cameras, of actual skydivers descending over sea and land during the day. Because of the cameras clipping information from the top end, it was discovered that a lot of the cloud detail was being lost when the shots were finally graded to night. They looked flat and featureless. We did a few shots where we were simply adding detail back in to the highlights, so that the colourist would have more information to play with. This was a simple case of tracking various noise patterns to the clouds and grading through them. Some shots were clearly filmed near land, so there was also a lot of horizon clean-up to do.

One shot in particular showed the skydivers descending directly above what looked like a mountain range. Initially, due to lack of detail, it was difficult to get a good 3D track, and because they skydivers were so far from the ground and clouds, there was little or no perspective shift. It therefore made more sense to understand them as being static at the centre of an environment, rather than falling down through one. With that in mind, a nodal track was done and an inverted “sea-dome” was created, which when filmed through the camera, matched the movement of the plate perfectly.

Another shot, initially bid as horizon-cleanup, ultimately required an entire environment rebuild when the director asked us to re-animate the camera. He wanted to pan from the parachutes over to their intended destination, the USS Boxer, Bainbridge, and Hamilton – which weren’t there when it was filmed. We used footage of the boats shot for other sequences, and painted up a substantial seascape and horizon to fill the frame of the new camera move. The look of the sea and respective positions of the boats were signed-off quite early on, but the move itself went through numerous iterations. Paul Greengrass had a very specific dramatic reveal that he wanted to make, in terms of timing and motion, and it took while to get that exactly right.

Can you explain more about your work for the screen inserts?

A large amount of the work we did on this project was graphical. From radar-displays to maps, emails, sniper-vision, video feeds – pretty much any image you see on a screen was work done here. Fortunately we have a great After Effects artist at Nvizible, Chris Lunney, who was able to oversee them all.

Chris was given a huge wadge of information from the production, detailing the facts surrounding the events of the Maersk Alabama hijack. From this he was able to extract important information like GPS, distance, direction, speed and time-of-day for scenes throughout the film. VFX Editor, Tina Smith, then supplied us with temporary placeholder graphics detailing the relevant information and correct timings, which we used as a starting point for our own designs.

From the beginning, it was clear that the emphasis should be on reality and that the graphics should resemble as closely as possible the types of software you would see in that situation. Not only should the graphics look correct, but the information that they displayed should also be accurate and tell the required story efficiently and concisely. Often, our screen inserts would be onscreen and adjacent to existing in-camera graphics, so it was important that they didn’t look incongruous.

There was a huge number of these shots, the majority composited by Charlotte Larive and Simon Puech. It was very grainy footage, therefore difficult to track and colour balance throughout a sequence. It being mostly invisible work does not make it easy – it was not, and they both did a fantastic job getting through it all.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

The biggest challenge was probably just to get everything, across the film, to look authentic. Because of the kind of film that it is, if you get any sense that what you see onscreen is an effect, the illusion is shattered. It might sound silly, but it has to look real. This is not such an issue in other genres, when the viewer is asked to suspend a little disbelief because the aesthetic or content is somewhat cartoon-y. When the director is striving for such realism, the smallest thing, from a patch of grain to an odd camera move can look wildly out of place and be a massive problem.

We had a really solid production and compositing team and great communication with editorial. From early on we felt like this was a really powerful film, and I think that everyone pulled together in part because they were very excited to be working on it.

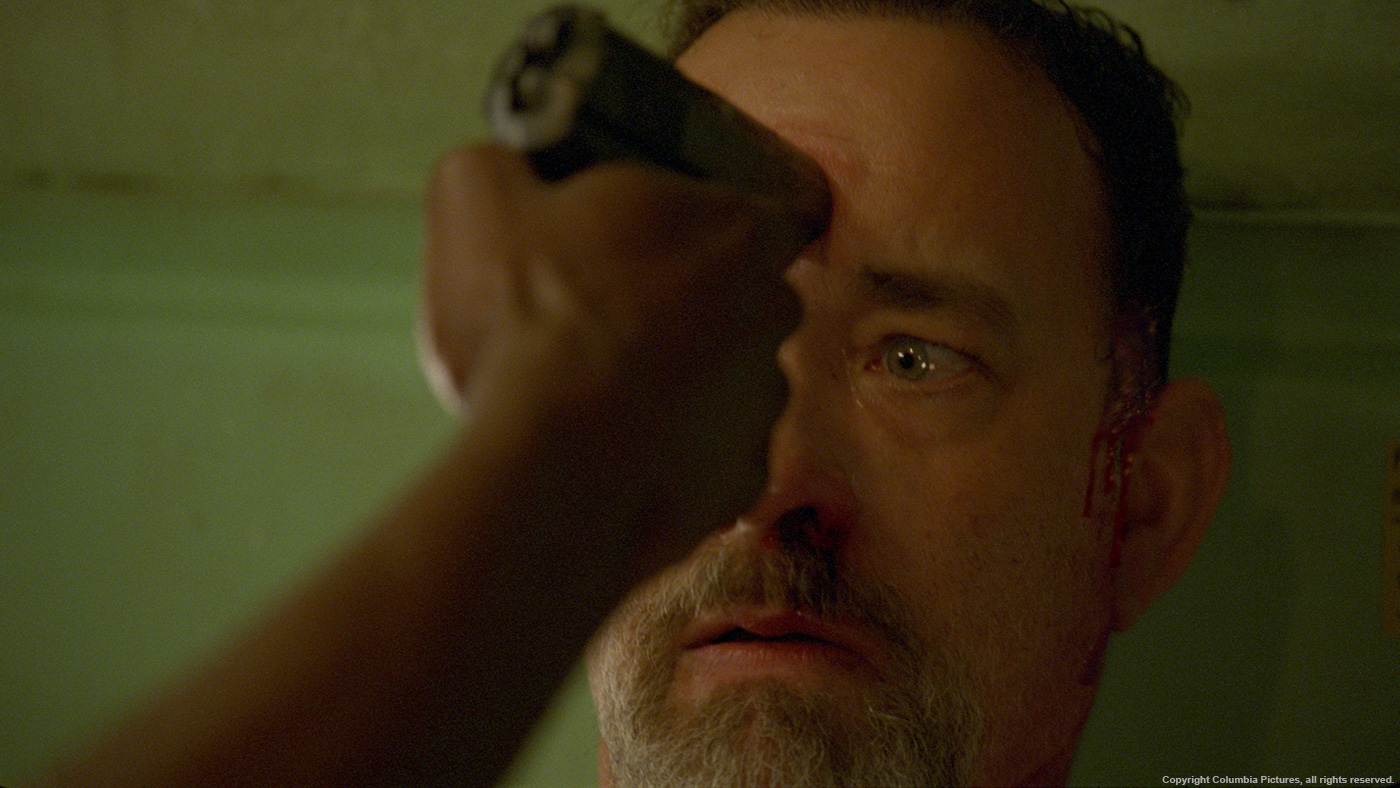

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

The sequence where Captain Phillips is being threatened with a gun in the lifeboat was tricky. We had to maintain the continuity of blood dripping down his temple through a large number of shots. They were all difficult to track, and getting the look of wet blood glistening wasn’t easy. Ultimately we used a number of stills rendered out of 3D and then 2D tracked in Nuke to get the texture, shape and movement of the blood, and then a number of compositing tricks to get the interactive light working. It came in very late in the production schedule, at a time when we thought we would have already wrapped. Gavin Digby took charge of this sequence as I was away, and I was very impressed and pleased with the results when I returned.

What do you keep from this experience?

Most of what we achieved is fairly invisible. It’s not a film that one might associate with VFX as it all looks so naturalistic.

The great sense of achievement comes from having people not know we did anything at all. The fact that it isn’t noticed is often the highest compliment.

How long have you worked on this film?

From Sept/October 2012 to January 2013.

How many shots have you done?

Somewhere between 180 and 190.

What was the size of your team?

Including production, around 12.

What is your next project?

I am currently working on a British film called SECOND COMING, and will be commencing work on a Working Title production, TRASH, soon.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

THE ABYSS, all JAMES BOND films, WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT,

and most recently, GRAVITY.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Nvizible: Dedicated page about CAPTAIN PHILLIPS on Nvizible website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2013