Andrew Jackson has a long experience in visual effects. He has supervised numerous projects such as KNOWING, HAPPY FEET TWO and MAD MAX: FURY ROAD. He talks to us today about his collaboration with director Christopher Nolan for DUNKIRK.

What is your background?

I grew up on a farm, both surrounded by, and fascinated with, the mechanics and physics of the real world. I think my practical approach to problem solving came from this early experience. After attending Art school in the UK, and later training and working as a model maker, I immigrated to Sydney Australia where I started my own model making and effects company. My grounding in the real world has influenced my whole career from early model making days, to practical effects and miniatures for film and TVC’s, right through the transition to digital FX, and up to the present day, supervising the VFX on films like MAD MAX: FURY ROAD and DUNKIRK.

How did you get involved on this show?

Dneg introduced me to Chris and we meet at their London office to discuss DUNKIRK. We quickly found that we both had a similar attitude to VFX; he liked to avoid it altogether if possible and I liked to film absolutely as much live action material as is practical, and only use the full CG approach as the last resort.

How did you feel about working with director Christopher Nolan?

I was obviously very keen to work with Chris. He has a reputation as a decisive and extremely efficient film maker who also makes great films. After meeting him I felt I would be able to make a valuable contribution to his next production – DUNKIRK.

How was this collaboration with him?

Chris is very collaborative. He is keen to hear other peoples ideas and encourages just enough debate to produce a workable plan. He has a strong vision of what the film needs, coupled with a lot of valuable experience from previous films. Throughout the shooting of the film I would check in with Chris and update him on what the VFX and aerial crews were up to. He would suggest things he would like me to shoot and we would review the results during dailies. After we had the aerial unit working well with the RC and the full size planes, Chris would take over and direct the action including the more complex scenes that included planes, ships, small boats, cast and extras in the sea.

What was his approach to, and expectations from, visual effects?

I really like Chris’s approach to visual effects. When reviewing some of the more subtle effects, like tracer fire, he would say it’s fine if they are almost not there. With the same minimalist goal in mind Chris would always encourage us to use absolutely as much of the original frame as we could, as well as using filmed live action elements wherever possible. All too often in modern filmmaking, visual effects is used to smooth out and correct every little inconsistency and irregularity, and the result can often feel polished but a little sterile and bland. Chris’s approach to both visual effects and film making in general helped to maintain the raw, gritty, naturalistic feel of the film.

How did you work with Double Negative VFX Supervisor Andrew Lockley?

Before DUNKIRK I had no experience working with large format film and the whole photochemical finish that is a huge part of all Christopher Nolan films. So having Andy as the Dneg supervisor was fantastic for me – he had worked on all the Dneg Nolan films and his knowledge of the way Chris likes to work was invaluable. Of course he is also an extremely talented supervisor in his own right and coming from a 2D compositing background was very complimentary to my more practical and 3D experience.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer and Double Negative?

We all worked very closely with Chris and his editor Lee Smith while they were cutting the film. They would send us shots for a very quick bash comp version, which they would drop back into the edit, the shots would then continue to be revised and refined until they were finished.

How did you work with the SFX and stunt teams?

I always put a lot of effort into building a good relationship with all the other departments on a production but especially the SFX and stunts. There is so much crossover between VFX and these two departments and we can all benefit greatly from a strong collaborative and supportive atmosphere. On this film I was very involved with the miniature planes that were built and operated by SFX supervisor Scott Fisher’s crew. Having managed the previs with Chris’s input, and understanding the feel of the shots and the story he wanted to tell, I was able to assist with the shooting of the aerial sequences.

Which stunts were the most complicated to enhance and why?

It might sound crazy but one of the trickiest stunt shots we did on this show was a stunt wire removal from a soldier in the bombing sequence on the beach. It was just one of those very fiddly paint fixes. There were three out of focus wires, over a long, full frame sand explosion, every frame was different and it took weeks of work before it was truly invisible.

Can you explain in detail how you created views of the devastation in Dunkirk?

I have to say that most of the shots of the town were largely in camera. Chris’s regular production designer Nathan Crowley’s art department had dressed all of the promenade, including covering a huge modern building with the facade of a period cement factory. There were still a few modern building in some shots that needed replacing, and we also added more smoke to augment the practical SFX smoke in some of the wider shots.

How were the crowd scenes of the British army waiting on the beach created?

Again a lot of the crowd scenes were primarily in camera. The art department built thousands of painted cut-out soldiers in groups of ten. These “fences” were arranged in rows behind the 1,000 plus foreground extras. We did add a few moving soldier elements to disguise the static fences in some of ground level shots looking along the beach. The main use of CG crowds was in the high wide aerial shots that showed hundreds of thousands of soldiers stretching far into the distance. For these shots we used a full crowd simulation built using photogrammetry from on-set stills of the extras.

Can you tell us more about their animation?

The animation of the crowd on the beach was mostly generic standing and walking sequences with some waving added for some scenes. We did, however, need to motion capture a library of actions for the CG crowd abandoning the sinking ship later in the film.

Dunkirk can be seen from a far distance thanks to two big smoke trails. How did you create these FX?

If they weren’t already in the original photography, the extra smoke plumes that we added were mostly from live action elements filmed by the VFX IMAX unit during the main unit shoot in Dunkirk. Chris was adamant that we use the IMAX smoke elements, completely unadulterated, exactly as they were. Some of the smoke that was added to the sinking ships was CG, but again it was mostly stolen from the original plate or from similar shots with practical smoke.

There are many dogfights in the movie. How did you approach these shots?

After reviewing hours of archival footage and flying reference we worked closely with Chris to develop the style of the aerial battle scenes for DUNKIRK. The next step was to apply this aerial dogfight language to the key story points in the script. Previs was used to further develop the sequences into a practical shooting guide.

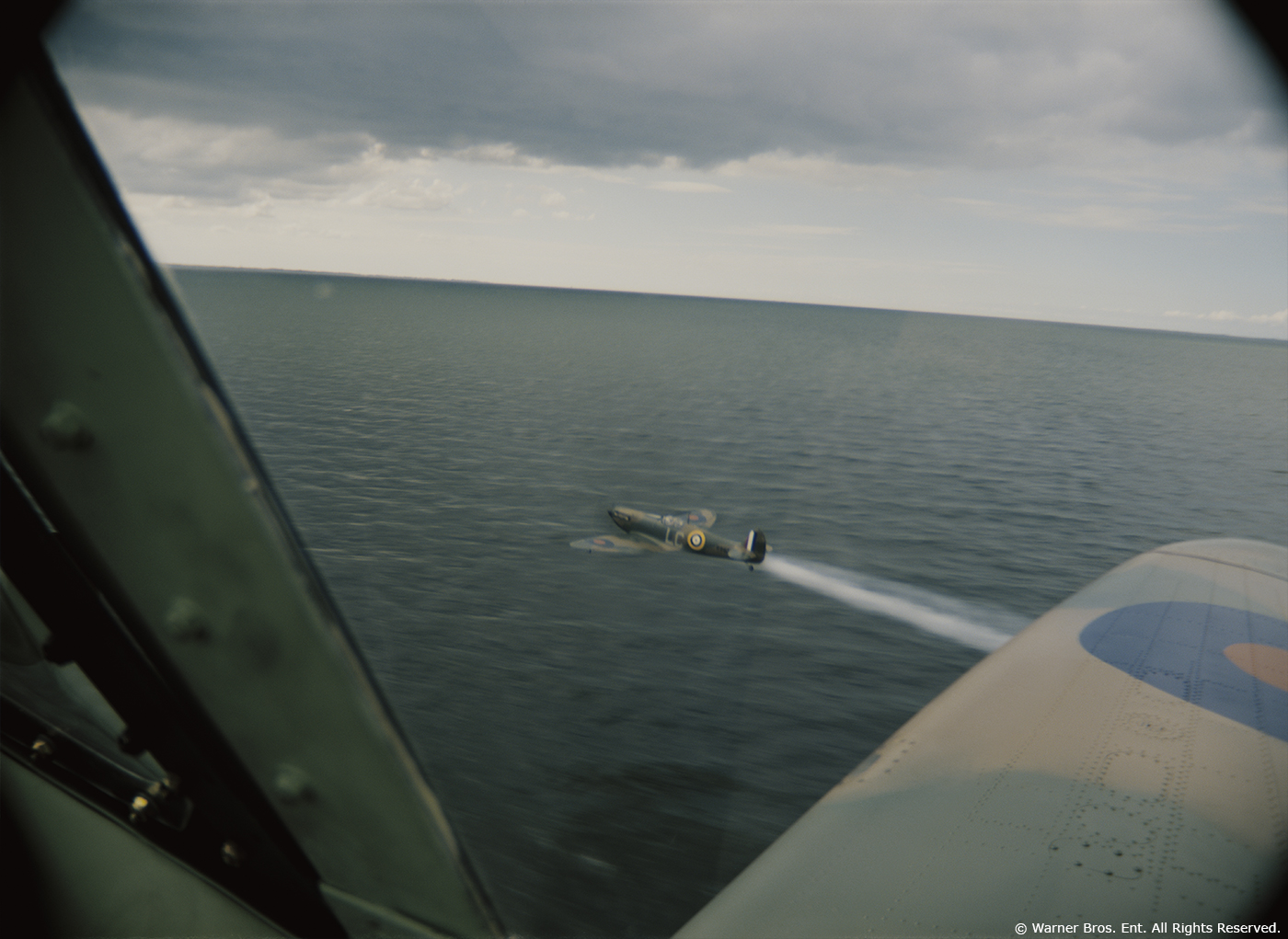

With the exception of a couple of distant shots, all the aeroplanes in the film were either full size vintage planes or large scale miniatures, all filmed on 70mm 15 perf IMAX cameras. There were three aerial camera platforms, a twin engine Piper Aerostar with rear and forward facing mounts, a shotover stabilised mount on a Eurocopter Squirrel helicopter and a Yak-52 with various fixed hard mounts. The approach to the aerial shoot was not to use the previs as an exact brief for every shot, but more of a sketch of the overall choreography and style of the action. Chris was very keen to avoid attempting to exactly reproduce the previs, shot for shot, but rather to embrace the unplanned events and the raw randomness of a live action shoot.

Can you explain in detail how the various planes were created, especially the Spitfire?

All the vehicles, not only the planes but also the ships and trucks, were comprehensively photographed and digitised using a Faro Lidar scanner. We built digital versions of all the hero planes and ships using a combination of photogrammetry and Lidar geometry as a base for modelling and textured with the stills from set. As I mentioned earlier the planes were largely in camera, we did however use parts of the CG assets to correct things like mirrored markings in reversed shots. We also used CG components to extend the tail on cockpit gimbal shots, stop the propeller and lower the undercarriage as the spitfire lands on the beach at the end of the movie.

How did you create the various plane crashes on the sea?

All the plane crashes were replica planes of various sizes actually crashing into the water. We did retime some of the elements in the live action plates and also some augmenting fire and smoke, but essentially the crashes were in camera.

There are a few sinking ships. Can you explain in detail how these shots were achieved?

There are three key sinking ship scenes – the hospital ship, the destroyer and the mine sweeper – and each was a quite different treatment. For the initial listing of the hospital ship I suggested a technique that involved filming the scene, with stunt performers leaping into the water, from two cameras simultaneously. One camera was static and one was on a crane dropping down from a starting position close to the static camera. The ship element from the moving camera was composited into the scene from the static camera. Because the same action of the leaping soldiers was in both plates, it was a relatively simple comp blending the two plates together at the waterline. This shot was followed by two shots of a half scale ship lowered into the water with some VFX cleanup of the swimmers and environment. The destroyer sinks at night and was filmed at Falls Lake Universal studios in LA using a full-size section of ship on a 2 axis hydraulic gimbal to simulate the sinking ship. The daytime sinking minesweeper scene was a combination of close up shots of a section of the ship on the same Falls Lake gimbal and wider shots with a full CG ship and crowd.

Many explosions happen during the show. How did you extend them?

The SFX department was able to create virtually all the explosions in camera, using either compressed gas or actual explosive charges. VFX did add a few explosions to some shots on the mole (the name of the sea wall used to load the troops onto the larger ships). For these we used shot elements with some particle effects to help integration with the live action extras.

How did you handle the challenges of the IMAX format and how it affects you work?

The main impact of working on an IMAX film is the resolution. On this film we worked at 6.1K. This requires all the work, including tracking, roto, modelling, texturing, animation, FX and compositing, to be done at a higher level to hold up. Reviewing the work is quite involved; after developing the shot and reviewing at HD res we would inspect each quarter frame at full res, followed by a 70mm 5perf test film out. If that looked good we would go on to an IMAX 15perf film out. If we found anything that needed attention it was a long way back and about a week before we could review a new version projected in IMAX.

Filming the miniature planes from a helicopter over water involved the successful execution of a series of tasks. In order to not lose sight of their RC planes after a successful takeoff, the RC pilots needed to be already airborne in the helicopter. The first of two planes would take off and loop around the airfield with the helicopter. As we approached the airstrip the second RC plane would takeoff and join the formation ready for the 15min journey away from the shore to the shooting location. Only about 50% of the takeoffs were successful and we lost a few planes on the journey to set. So we would arrive over the set with the ships, cast and extras all set for action…. “Roll camera” and it jams! Back to base, land everything, fix camera, start again. We were shooting the miniatures at 48 fps and at that frame rate on an IMAX camera, a 1,000 foot film roll lasts for 90 sec! Despite all these extra challenges, or maybe because of them, there is a great sense of achievement and the results are so beautiful that it’s all worth it.

Are there any other invisible effects you want to reveal to us?

There are shots of the actors in a Spitfire flying alongside another real Spitfire that were completely in camera. They were in the front seat of the Yak camera ship, with a modified cockpit to look like a Spitfire and an IMAX camera mounted on the wing.

For other close-ups of the pilots the SFX team built a Spitfire cockpit on a three-axis gimbal. The plan was to shoot it on a car park roof or another high building. After my recent experience introducing movement to static desert shots on MAD MAX, I knew that if the horizon was in camera, generating movement in the foreground was fairly straightforward if it was needed at all. We found a location on a cliff overlooking the ocean where we were able to achieve a number of these shots in camera. Shots with more extreme banking needed a little cleanup of rocks and shoreline, and shots looking down the side of the spitfire needed a CG tail extension.

There are a number of shots in the film that needed water patches to cover boats and crew equipment as well as extending water at the edge of frame. These were achieved with a combination of CG water and 2D patching from the plate. We also added CG water under the plank crossing the bomb crater that Tommy and Gibson carry the stretcher across.

What is your favourite shot or sequence and why?

I love the sequence of the Spitfire landing on the beach. It is a beautiful scene. The sequence was originally slated for VFX, thinking that it would be impossible to achieve in camera, but the pilot, Dan Friedkin, was able to actually land on the hard sand. We did still do a fair amount of work replacing the spinning prop with a stopped one and replaced the static undercarriage with a lowering version.

What is your best memory on this show?

Chasing a Spitfire and a ME109 in the Aerostar camera ship while filming the dogfight scenes.

How long did you work on this show?

1 1/2 years.

What is your VFX shot count?

429.

What was the size of your team?

260.

What is your next project?

Don’t know yet.

What are the four movies that gave you a passion for cinema?

It’s difficult to name just 4 films but these are some of the films that have inspired me over the years:

BLADE RUNNER – a visually stunning and completely convincing world.

TERMINATOR 2 – great practical effects and CG for its time, and a great story.

A lot of the films I love have little or no effects like LIVES OF OTHERS and WALK THE LINE.

In the end, it’s the whole world of film making, compelling storytelling and engaging imagery, that is inspiring and so rewarding to be a part of.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Double Negative: Dedicated page about DUNKIRK on Double Negative website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2017

I can appreciate the work put into this movie by the special effects team, however some things just came up very short, which didn’t need to be. The fake looking exhaust pipes that were attached to the front engine cowling of the Yak used in the on-board Spitfire scenes were all the wrong shape and not convincing at all. To add to this problem the Yak’s actual exhaust pipes located underneath the engine cowling were still visible in many of the segments looking forward over the nose…. this was very un-Spitfire. Additionally, the steering chain and cable linkage attached to the tailwheel fork of the Yak were also very non-Spitfire and gave the tail view images of the “apparent Spitfire” a sub-par appearance. The scene of the Spitfire “gliding” over the beach with its propeller stopped is completely un-natural as it is shown very nose high (which would lead to a stall in short order in a Spitfire with no power). Also the elevator position for this high nose angle is not correct. There would need to be more elevator-up to achieve this nose high position with no power. The elevators are shown in the normal cruise position. The glide angle of a Spitfire with no power approaches that of a brick, so any power off flying scenes should all show the Spitfire in at least a shallow dive to maintain an airspeed above the stall. Finally the beach scene with the Spitfire on fire after landing shows the propeller attached to this burning mock-up with a long supporting extension tube….. no engine block. It looks completely fake and ruins the scene. Sorry, but as a pilot and someone who works on aircraft, all of these deficiencies detract from what was otherwise a very moving film.