Kirk Shintani worked for many years as a freelancer before joining teams of a52/elastic. In the following interview, he talks about his work on the main title of GAME OF THRONES for which he received an Emmy Award.

What is your background?

It’s a little unusual. I graduated from UCLA with a degree in Psychology, then realized that it really wasn’t what I wanted to do the rest of my life. Woops. It wasn’t until my best friend mentioned he was interested in 3D that I really thought of this career as a possibility. So I did my research and started taking classes at Gnomon School. After I graduated from Gnomon’s Certificate Program, I freelanced, took a staff job, freelanced some more, and about 4 and a half years ago, decided to stay at a52/elastic.

How was the collaboration with the production for this title?

Everyone at HBO was really great. They let us loose on this job and were really open to anything. Dan Weiss, David Benioff, and Carolyn Strauss were very supportive and gave us a lot of encouragement. It’s rare to get a chance to work on a project that has so much creative freedom. They put a lot of trust in us to do something unique and cool and I think having that support really shows in the final product. HBO understands the process and really puts their faith in it.

Can you tell us how did a52/elastic get involved on this project?

It actually started two years ago with preliminary designs. We explored the possibility of vignettes to orient the viewer originally. But in the end it slowly evolved into a title sequence to accomplish the same goal: To introduce the viewer to this large, very unique world and give them a better understanding of the territorial boundaries of each faction.

Which indications and references did you received from the production?

Initially we received tons of imagery from production to help us define which locations were important and to give us a good indication of form and scale. We also used the production art to figure out what the best way to represent the unique locations in the language that we developed for the title sequence. As the production art was refined, we would update our models accordingly. It was pretty amazing to get a chance to see the concept art from production, because it gave us a great sense of the shows direction and mood.

What was the main concept for this opening title?

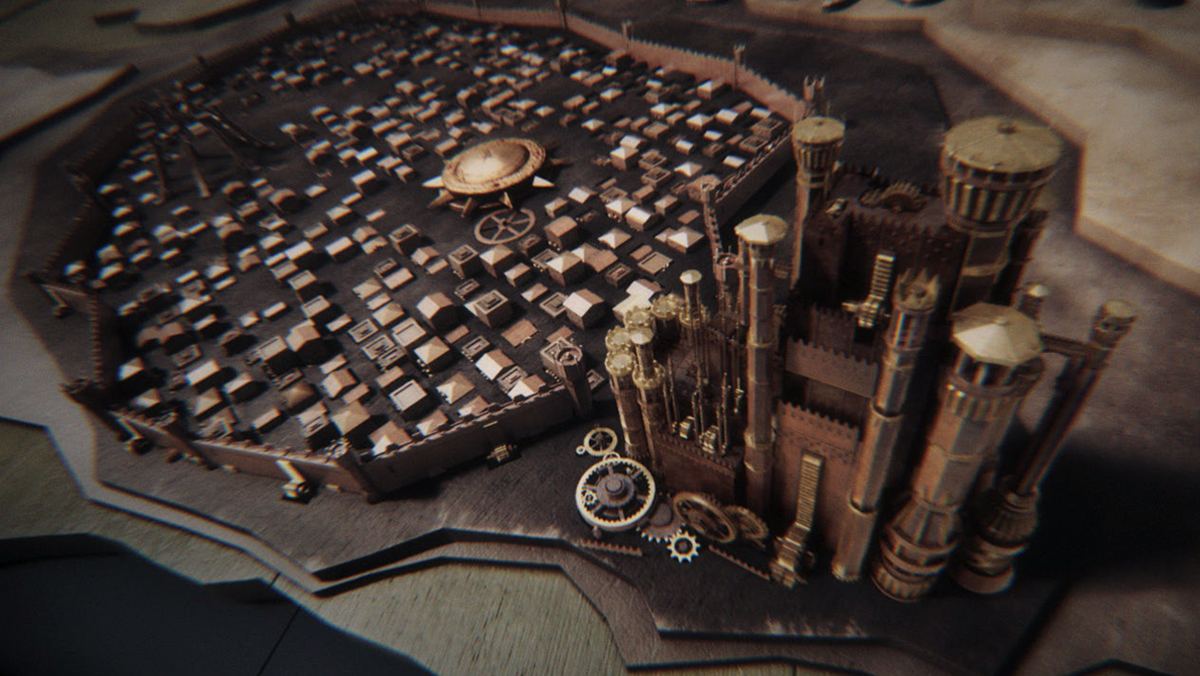

It’s Retro-Futurism, mixed with da Vinci mechanicals and a dash of ‘medieval steam punk’ for flavor. We wanted to avoid a flat 2 dimensional map at all costs, so we spent a lot of time trying to find a way to keep dimension in the map but still allow us to move from spot to spot as easily as possible. The Retro-Futuristic inverted planet gave us a great foundation to build on. It allowed us to move from location to location and gave us a much more elegant way of departing and arriving at locations. A big benefit was that we could look anywhere on the map and never have to think about a horizon line. It also allowed us to show a large portion of the map while we were traveling between cities. A flat map would have been much less elegant, requiring us to tilt up for each move to show our destination as we traveled toward it.

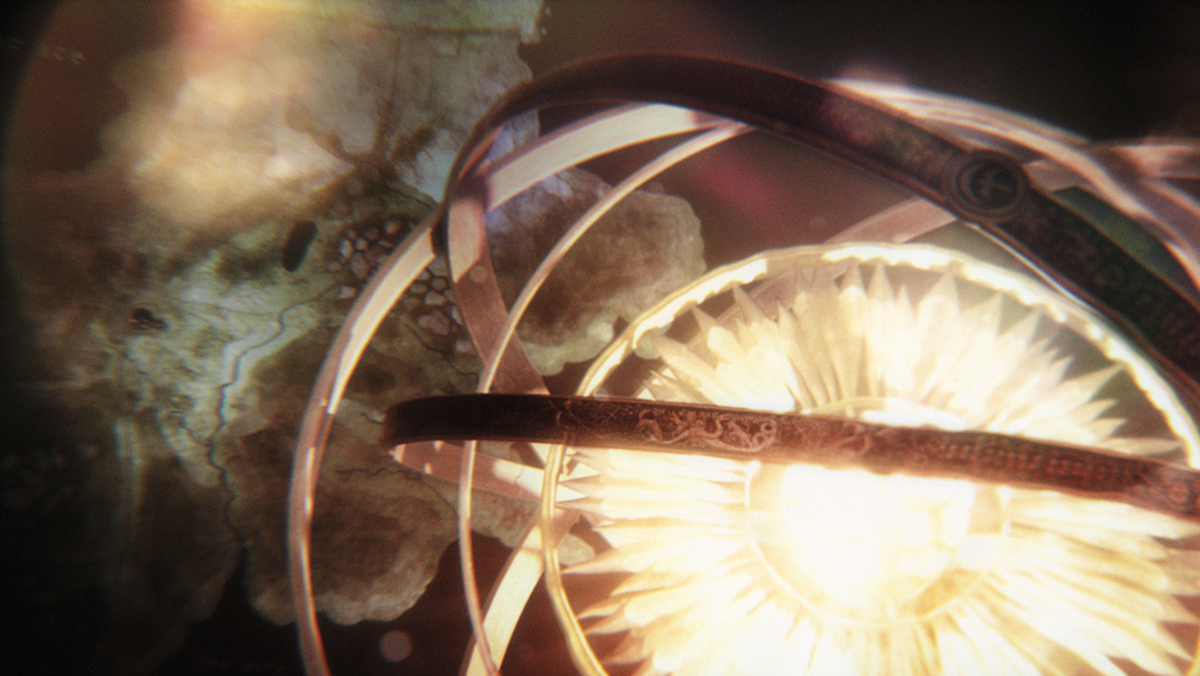

How did you create the beautiful Astrolabe?

It started with reference. Lots of reference. Rob Feng was always collecting imagery and thinking of new ideas. We took inspiration from automata for the astrolabe, and translated that into a rough model in Maya to work out the dimensions, number of bands etc… Henry De Leon then painted the mosaics that we see engraved in the bands.

From there we took their digital paintings and used them in zBrush to generate a highly detailed engraving as displacement and normal maps and Joe Paniagua added the wood grain textures, the cracks and the animal heads to really make it feel tangible. Maya and vRay were used to shade and light the detailed model, and Eric Demeusy took our renders and cranked it up a notch by adding all the heat haze, camera shake, light blooms, and chromatic shifts.

Can you tell us more about the design for the cities?

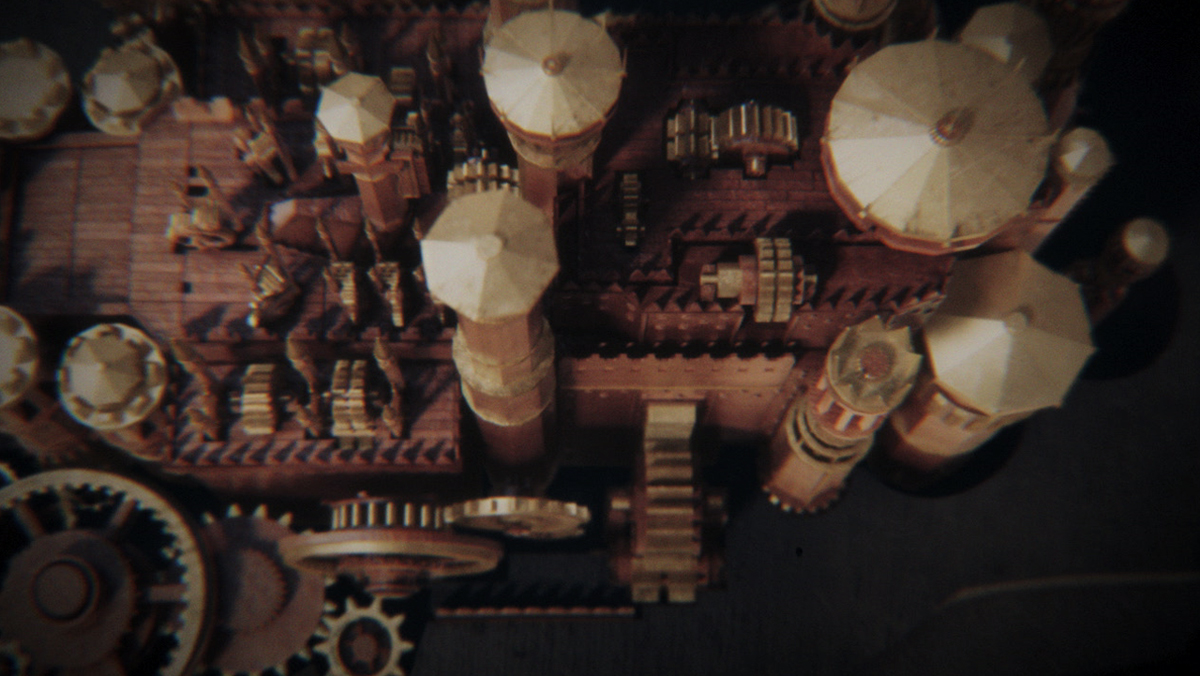

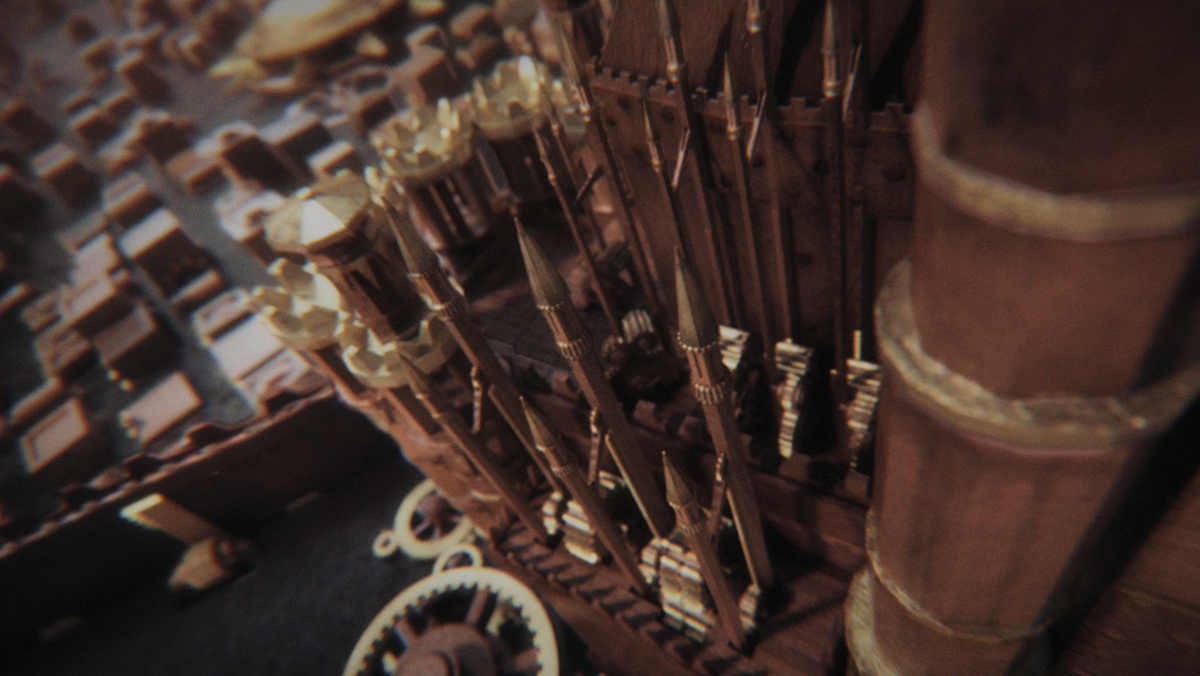

We spent a good portion of our time trying to define a ‘language’ we could apply to our world. We wanted to make sure that the cities felt had made, so we looked at da Vinci’s mechanical concepts and actual builds of his ideas. It’s really amazing how forward thinking he was. I think it really helped us generate boundaries for our world. His ideas were grounded in the technology of the time which was great for us, because it gave us a base to work from. We always reminded ourselves that if we couldn’t make it with a saw and wood chisel then we needed to re-think the design.

Can you explain to us in details the creation of the different cities and environment?

We wanted to make sure that we thought everything through from a style standpoint before we got too far along in 3D. Rustam Hasanov did a great job of capturing the idea and feeling in his initial concept sketches and Chris Sanchez brought those concepts to life by rendering them in Photoshop. We then took the concept sketches and renderings and the basic da Vinci conceptual framework, and applied it to the locations. We wanted the viewer to feel like the city was being driven by something larger than just the location and that it had an underlying mechanical structure. Modeling was challenging because it was so closely tied to animation. There was quite a bit of back and forth between modeling and rigging because of the nature of the locations. They all had to animate out from underneath the base land mass, and they had to be mechanically possible, so modelers had to think about how to actually build the cities practically. We built many different gear variations to try and find what worked, and how to change the direction of force depending on the needs of the structure. There’s so much detail that you don’t see in the final sequence!

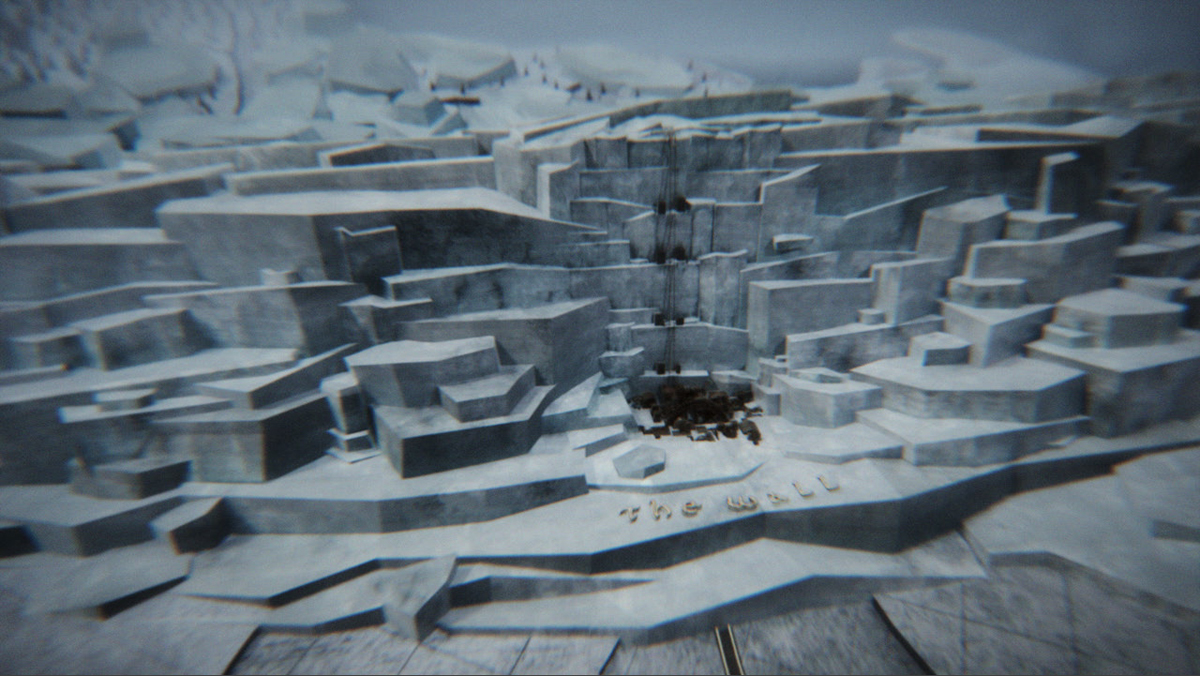

We also spent the time to make sure each location was unique, but still maintained the basic look we established. For instance, Winterfell is a bit worn, The Wall is weathered, and King’s Landing is much more pristine. The world itself was a little more challenging, and we wanted to be sure it tied everything together. Things like the trees scattered over the surface were just simple shapes, and the mountains were made of flat wood panels, keeping in line with the ‘hand-built’ nature of the sequence. The larger land masses were tiered to give it a feel of layered wood panels with distressing and cracks wherever the most movement would occur. We also whitewashed the wood the further north we traveled to represent the change in climate around The Wall. The water was done with Maya nCloth to give the feeling of rolling waves, but again still feeling hand made. We embroidered the type into the cloth, and built metal plaques for locations on land.

Can you tell us more about the setup and the rigging for the animation of the cities?

John Tumlin and Dan Guttierez both did a great job working with our modelers to speed up the process on the setup and rigging side of the pipeline. There were really only a few things that were traditionally ‘skinned’. Vaes Dothrak and the tree in Winterfell’s ruins were the expections. Most everything else was dependant on group and transform setups. John spent some time setting up scripts to automate some of the more complicated gear and cog mechanicals and they both spent a lot of time making sure the rigging was flexible enough to accommodate inevitable tweaks and changes to the models.

Did you used procedural animation or rely on keyframe animation?

In the end, we used both scripted animation and keyframe animation. The gears and cogs were scripted to handle the interaction in the larger mechanical chains to make our lives easier, but we keyframed all the major elements. The great thing about the set up was that we could start with the script controlling the basic gear interaction, then go back in and add offset animation and sticky gears and shuddering as an additive pass. If we had to hand animate each gear interacting with each other, we’d still be animating today! I don’t know how many there actually were, but there were more than we’d want to animate by hand.

Can you tell us more about this great render look?

This was our test bed to switch to vRay. It was basically a trial by fire, and we only got singed a little bit. We did initial tests with a rough version of the Pentos model, and were blown away by how quickly we got the renders looking great. We were convinced that we’d be able to execute the job with a brand new renderer based on that test. A testament to Ian Ruhfass, he spent the time to test and set up vRay as well as set the lighting approach and look very quickly. There were some technical hurdles along the way during the switch, like render farm implementation and locking down a build we were happy with. But overall we were impressed with vRay. Every build seems to be getting better and better, and it’s pretty stable already. DOF and Motion blur were very fast out of the box.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieved it?

The biggest challenge was making sure we were delivering a title sequence that showed the viewer the scope of the show in a grand and elegant way. GAME OF THRONES (GOT) covers quite a bit of ground and travels to the far corners of George R.R. Martin’s world. We needed to show that scope and detail without having the sequence revert to a fly-over on a 2D map. The inverted sphere concept allowed us to keep the world dimensional and provided us with some shortcuts from place to place.

Congratulations for your Emmy Award. What was your feeling about this?

It’s an honor just to be even considered for an Emmy. There were so many people who contributed to this project. It was a great group of guys to work with. Everyone was very enthusiastic, and put some of their own creativity into the job. The GOT team was one of the most balanced and collaborative teams I’ve had the pleasure of working with and HBO gave us so much freedom to explore different ideas. Carolyn Strauss, David Benioff and Dan Weiss we always very encouraging and supportive and we wanted to be sure that we delivered a sequence they could get excited about. Personally, I wouldn’t be doing what I love if it weren’t for 4 people. The late Nobu McCarthy inspired me to follow my heart. My parents gave me the chance to do what I love. And my fiancée Michelle is the most patient, understanding and supportive woman I have ever met.

What are your software and pipeline at a52?

Maya – vRay/Mental Ray – Rush – AE/Nuke – flame/smoke.

Dan helped us implement a practical referencing and publishing system that fit our needs and wasn’t too involved or cumbersome that it would be hard to get up and running. This allowed us to work more collectively, and gave the artists some freedom to make changes on the fly without having to worry about updating assets. vRay’s render layers made breaking out passes a breeze and allowed the CG team to give the compositors the passes they needed without much effort. We try and stay pretty nimble when it comes to software and technology. The industry changes so quickly I think it’s important to be able to adapt the pipeline according to current needs.

How long have you worked on this opening title?

Actual production was about 4 months.

What was the size of your team?

The CG team consisted of 8 people, for varying lengths of time. In all, I think there were about 24 people involved in the creation of the GOT title sequence.

What did you keep from this experience?

You never know where you might end up in the future. I never thought I’d be working on an Emmy Award winning project when I was a Psychology major in college, but things have a way of working out I guess. If you do what you enjoy, everything else if gravy and I really enjoyed working on this project. I realized after we wrapped the job, that the long hours and the pressure of delivery pale in comparison to the joy of creating something unique.

What is your next project?

GAMES OF THRONES Season 2!

What are the 4 movies that gave you the passion of cinema?

BLADE RUNNER – Cinematography at its best. Lighting was a character in the film and always active in the frame.

PIXAR SHORTS – Inspired me to simplify, and showed that you don’t need a complicated and extravagant production to tell a good story. In the end it’s about execution and not complexity.

SPACE BALLS – Comedic timing can be applied to anything. A pause is sometimes funnier than a scream, and Mel Brooks is a genius!

THE USUAL SUSPECTS – Just a great movie, period.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Elastic: Official website of Elastic.

– Art of the Title: Article about GAME OF THRONES main title on Art of the Title.

// GAMES OF THRONES – MAIN TITLE – a52 / Elastic

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2011