In 2016, Guillaume Rocheron explained to us the work of MPC on BATMAN V SUPERMAN: DAWN OF JUSTICE. He talks to us today about his work as Overall VFX Supervisor on GHOST IN THE SHELL.

How did you got involved on this show?

I met with Rupert mid 2015 after I received a phone call inviting me to discuss the film. I didn’t have a lot of information other than that it was for GHOST IN THE SHELL, which was tremendously exciting as a long time fan. We talked about all sorts of ways that we could create the visuals for the film and that’s how I started on the film. Fiona Campbell Westgate, the VFX producer, had already started, so we hit the ground running working with Rupert and production designer Jan Roelfs, DP Jess Hall to define how we would create the world of GITS.

How was the collaboration with director Rupert Sanders?

Great, Rupert is not only a VFX savvy director but he also collects and curates art from different mediums which makes him a very effective visual communicator.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

Rupert spent a long time planning the world of GITS and curated a huge collection of images, GIF files, art installation that inspired him. He wanted a world that felt tactile, with a certain patina to it. For this reason, we decided to use as many real locations and animatronics for the shoot where most projects would go completely digital.I think mixing the techniques really helped giving a patina and style to the visuals.

How was your collaboration with VFX Legend and Supervisor John Dykstra??

Working along with John was an absolute pleasure. John came on board for the last few months of our compressed post schedule and helped to divide and conquer so I could spend more time on the ground at MPC Montreal in order to facilitate the creative turnaround because as had so much to do with little time.

How did you organize the work with VFX Producer Fiona Westgate Campbell?

?Fiona and I spent a lot of time defining how we would achieve the work, balancing out what we could do practically with the team at Weta Workshop and what we would do digitally. Even the digital part in post got us to think out of the box because we knew there was an immense amount of design work that had to go into the visual effects. Our post production schedule was fairly short and GITS had a fair amount of design work and new concepts that had to be developed as we were making the shots. MPC was our lead VFX facility but we also hired Ash Thorp and Territory Studios to exclusively focus on designing the Sologram advertising throughout the film. At the same time, we had MPC’s art department led by Ravi Bansal and Loic Zimmerman designing key shots and looks for the city shots.

What was your feeling to work on the adaptation of this cult anime?

GITS was a big part of my film education growing up so I felt very creatively invested in making the visuals for the film. In France, where I grew up, our 80’s and 90’s generation received a lot of influence from Japanese anime and manga as it was, for a few years, most of the kid’s programming on TV.

Can you describe your work during the preproduction and the shooting??

Designing and shooting the movie was very interesting because we were aiming to create a fully immersive world, with a lot of new imagery. Pre- production was generally split between reviewing previs and boards, meeting with the heads of the other department to define the best way to shoot each scene. We had a 75 day shoot in New Zealand and 10 in Hong Kong, which was really short and intense. Ben Brown, from MPC, helped me out with the 2nd unit and more specific VFX element shoots as I was looking after the main unit. Because of Rupert’s desire to use a lot practical photography as a starting point, I tried to avoid full green screen sets as much as possible, even though some sequences like the water courtyard fight required it. But we made those decisions by design and not by default. A lot of our exterior shots, were shot in the streets of Hong Kong. Even though we knew we would replace a lot of it down the line to create the futuristic version of our world, it gave us incredible material to work with, capturing accidents and details that just helped to keep the world feeling authentic.

How did you split the work amongst MPC and the other vendors?

MPC was the lead vendor, with Axel Bonami and Arundi Asregadoo as VFX Supervisors. I have known both of them for know for many years. Territory Studio and Ash Thorp were our `solograms advertising agencies`, creating 3d assets that MPC could use to populate the city shots. We also worked with a team from MPC Design to visualize the world’s interface technology, hologlobe communication, and complex hologram deconstructions of the Major and Kuze As the movie and sequences evolved, we tasked Atomic Fiction, Framestore, Method Studios and Blacksmith with additional one-off sequences.

How did you work with their VFX Supervisors?

We held daily reviews through cineSync for the first half of our schedule and then in person and cineSync when I was down in Montreal. Our goal was to get the feedback loop to be as fast as possible because we were dealing with a lot of very creatively challenging sequences. But everybody really stepped up their game and allowed us to deliver the movie on schedule!

Can you tell us more about the previs process?

We had a small, 5 people strong, previs team that we assembled in New Zealand, led by David Scott. We really started previs 3 months before shooting so we had to be very mindful as to which sequences required it and what we were trying to get out of it. David and his team did a brilliant job at visualizing complex sequences like the Deep Dive and the Tank Battle.

How was your collaboration with Weta Workshop for the various cyborg parts and other props?

Richard Taylor and his team were really fantastic to work with. They have just this versatile pool of talent and were very collaborative. The Shelling Sequence is a great example of our collaboration; we found a great balance of practical and digital effects. Following the same logic, we used animatronics and masks for a lot of the robot geishas in the hotel and used a CG version of them for more complex movements. Weta also made miniatures for the futuristic skyscrapers, that we used as a rapid prototyping tool. Shooting miniatures is complex and expensive but using them purely to design the type of architecture we were after worked wonderfully using kit-bashing. We ended up with 8ft tall buildings that Rupert could see for real and tweak. We then treated them like set pieces, that we 3D scanned and texture shot in order to create a CG replica that we could then use to populate the shots.

Can you explain in detail about the recreation of the iconic opening sequence of Ghost in the Shell?

Rob Gillies, the workshop supervisor at Weta, and I spent 10 days in a small smokey set in order to shoot all the practical elements we made for the sequences! As I mentioned before, we looked carefully at the Shelling sequence to find a good balance of puppets, animatronics and CG. In the end, we settled on making a 1:1 scale skeleton and a 1.5:1 scale skull animatronic so we could shoot foreground elements for the first third of the sequence. The backgrounds were digital, along with additional treatment to make it all feel underwater. As the shots are getting wider or the transformation is getting more organic, MPC created all CG shots. But for example, the body coming out of the white liquid is practical: we used a mannequin filled with concrete, sunk it into a pool of thick liquid made by special effects and shot it at 300 fps on a Fantom 4k camera.

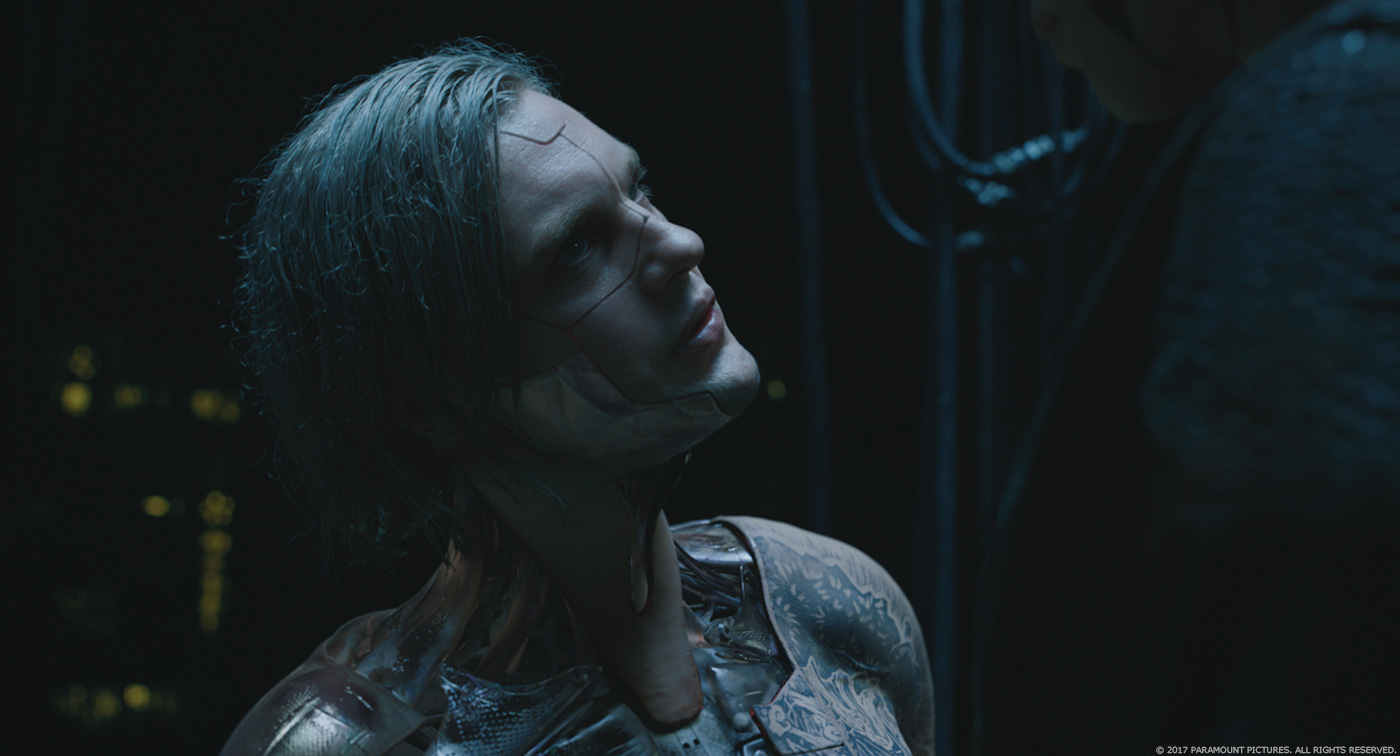

Can you tell us more about the cyber-enhancements of the Major, Kuze and the Geishas?

?Our main cyber-enhanced character was Kuze. As he was supposed to be an earlier, incomplete version of Major, we designed to create him as a hybrid live- action and CG character. Sarah Rubano, our prosthetic supervisor, designed some applications to create edges for the main panel lines on his face and chest but everything else is roto animated and rendered to Michael Pitt’s performance and seamlessly blended to the actor. Kuze was incredibly challenging to create because we avoided designing him with hard transitions between CG and live action so he would look truly unusual and disturbing. In the end, I don’t think that you feel that you are watching a CG character which was our main goal.

The movie involved many slow-mo shots. How does that affects your work?

Most of the slow motion work we did was for the water courtyard fight, that we shot pretty much entirely on the Phantom 4k at 300fps. We wanted the sequence to be a ballet of water arcs and floating droplets. At such speed, you’re not only registering the complexity of the water motion but also have a chance to see it’s surface tension which required MPC’s team go a level beyond for their water simulation and rendering.

Can you tell us more about the various flyover shots?

The “Ghost Cams”, as we ended up calling them, were one of the first things Rupert, Jess Hall (the DP) and I talked about on the movie. The idea was to create shots floating through the streets, establishing the world and taking the audience from one point to the other without being helicopter shots or establishers. We created 5 of those in the movie. I prevised them myself using some Google Maps imagery and simple buildings because we wanted to precisely choreograph them. These shots were designed to be completely CG with a transition to practical green screen plates when landing on the characters. In order to have a starting point, we devised a reference stills shoot plan in Hong Kong that would allow us to reconstruct in 2.5D parts of the city. The next challenge was to populate the world, with hundreds of solograms, people, cars, futuristic architecture etc.. The opening Ghost Cam shot is around 1.5 minutes long and is one of the first shot started and last finished.

Did you received specific indications and references for the city and the holograms??

Rupert had developed the concept of Solograms, which are giant volumetric projections throughout the city. Unlike holograms that are like a more advanced version of our TV, solograms are almost solid objects, lit by the environment they are projected in. Finding a way to create them had been a challenge because we either had to create completely CG actors or organize a motion control shoot of pre-lit actors and pre-recorded city camera moves. None of the options were really viable as we were talking of putting a huge quantity of them in every shot. So along with Dayton Taylor, of Digital Air, we designed a 80 camera system that allowed us to shoot the sologram actors in movement, and re-create a 3D moving version of them using motion photogrammetry. MPC took the data from the 80 cameras, at 24fps and generated upward of 30,000 3D scans in order to reconstruct the actors in movement. We then created new software and techniques to voxelize the moving data and be able to manipulate it into our shots.

What is your favorite shot?

I love some of the Ghost Cam shots we did as I think they establish the world of the movie in a very neat way. There’s also a couple of shots in the Deep Dive, where Major navigates the memory of a Geisha Bot, that I like because they show memories in very visually interesting ways.

Which sequence was the most complicated to create and why?

I think the world in general was complicated technically and creatively to create because we tried to make unconventional images with the solograms. The water courtyard fight, was complex because of the high speed choreography and the Deep Dive, because it was just really out there in terms of concept and it took us many versions to find satisfying visual and storytelling combinations.

What was the main challenge on this show and how did you achieve it?

For me, the main challenge was the amount of VFX design work that was required while we were doing shots in post. The world, with all its solograms was a key component in presenting the audience with our cyber-enhanced world from our movie. In every shot, the multiple ads are all designed, positioned and tailored very specifically… and there’s hundreds of them!

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

None really because if a shot prevented me from sleeping on this movie, I wouldn’t have slept for 5 months straight!

What is your best memory on this show?

When MPC showed me their first processed, animated and reconstructed sologram in a shot. We took a leap of faith in designing this camera system and technology to create this unique aspect of the world of the film and it was a relief to see that after many months of work, design and shoot, it all clicked into place.

What did you keep from this experience?

I really enjoyed having the opportunity to create some fresh imagery for the film. Designing the world and characters was a lot of fun and challenging. I also want to mention how I impressed I was with the artists dedication and passion throughout the whole process and I hope that everyone involved in the VFX is proud of the images they created.

How long have you worked on the movie?

20 months.

What is your next project?

To be announced soon!

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

MPC: Dedicated page about GHOST IN THE SHELL on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2017