Back in 2022, Mark Bakowski showcased ILM’s visual effects on No Time To Die. Following that, he worked on Jurassic World: Dominion and the Willow series. Today, he talks about his latest work on the sequel to the legendary Gladiator.

How did you get involved on this film?

I think I was incredibly lucky, to be honest! I’d just finished Willow, the streaming series that was briefly on Disney Plus. At the time we felt it had all gone well so there was much talk of going back for S2 etc. so I thought that was my future – which was fine with me.

Then my boss said do you want to do Gladiator II as production supervisor? How can you say no to that? That said, as I was going into it straight after Willow with no break a tiny lazy part of me thought if I didn’t get it and waited for S2 of Willow then it wouldn’t be a disaster. Glad I didn’t listen to lazy me.

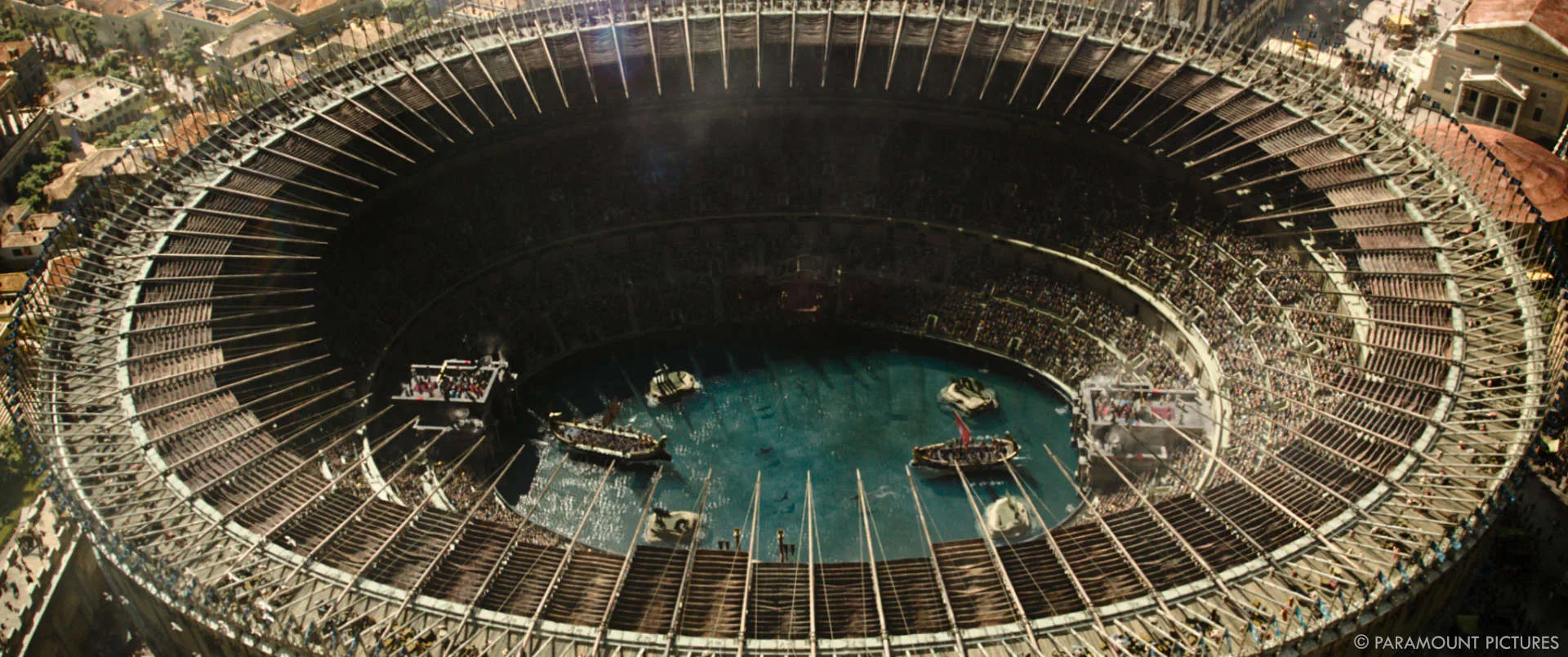

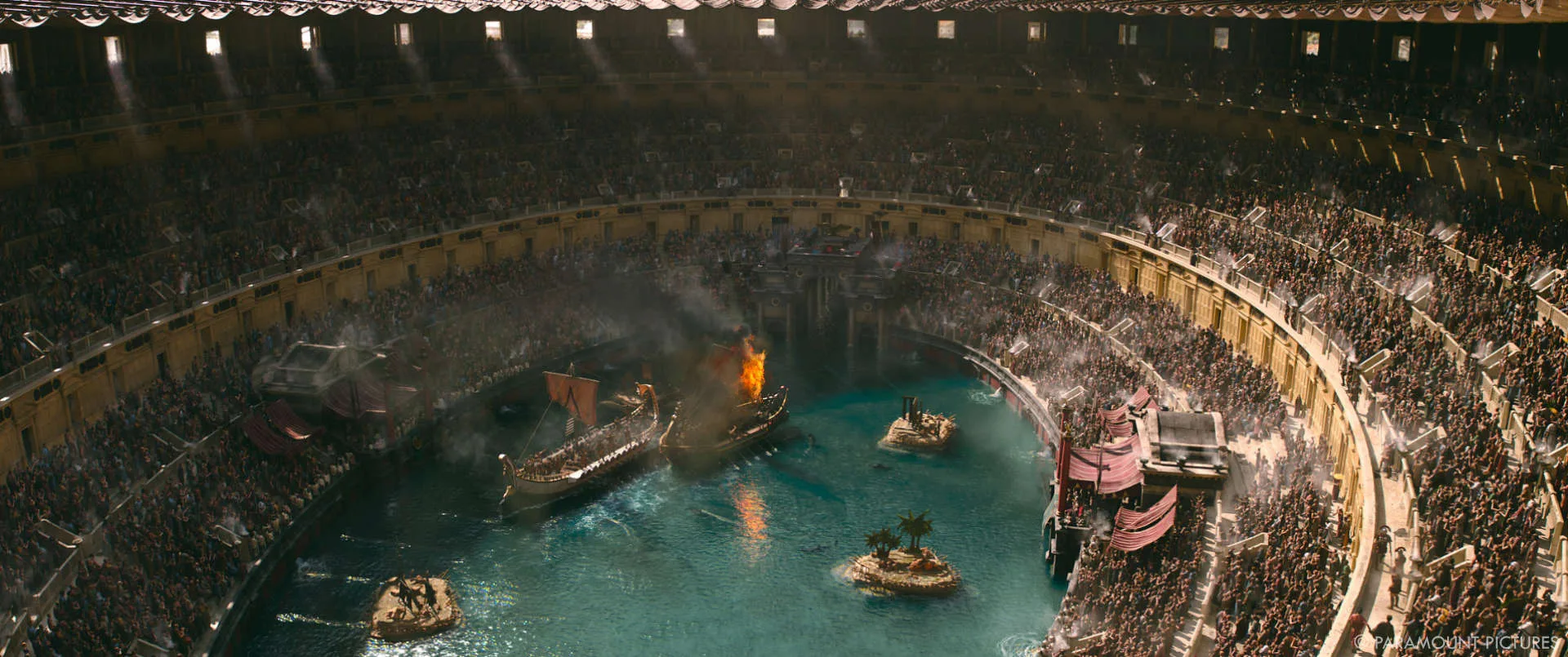

Anyway next thing I know I’m talking to Ray Kirk the executive producer and one of Ridley’s key people. He’s pointing at pictures of Colosseums with ships and water–stabbing them with his finger and looking at me! I guess somehow I made the right noises and I was on the show.

How was the collaboration with Director Ridley Scott?

I could say so much about this, there’s so many stories- but I’ll keep it brief considering how many questions there are in this list. He’s obviously a visual genius with such an eye for composition, such visual flair. But I assume most people who like his films will be aware of that. I guess I took away that he’s a lovely man, very funny – he hides it under a gruff sweary exterior much of the time of course. You get to listen to him direct on channel 1 of the production radio as he shoots. Talking in the camera, the set dressing, the actors it’s so educational and by turns amusing. They should have used it for Blue Ray / DVD commentary if those still exist. He makes the big calls on the day. He knows what he wants but he’s not unreasonable at all. He’ll listen to you–he may agree or he may not but you feel you can tell him your concerns and reasons and then he makes the call.

It’s also old school big Hollywood film making. It’s just big–and that comes with Ridley right down to the cigar smoking. I’m not sure there’s many more experiences of that scale out there beyond maybe the Bond movies.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Nikki Penny was VFX producer. I think we had a great relationship and worked really well together. She’s very smart. We both have our areas of responsibility but of course they overlap in every way, it’s just a question of emphasis. If I want to do X and Y then there are implications of time and money etc. and vice versa. So we’d talk things through, set a plan, put in assumptions and then react when things changed throughout. If Nikki had a concern she’d tell me and not just financial etc. but aesthetic. She’d call out the emperor’s new clothes as required. It’s good to have a second opinion with so much going on–as long as that person has taste and understands VFX which of course Nikki does.

How did you choose the various vendors and split the work amongst them?

Well being ILM based myself there was never a question ILM was going to get a large chunk of the show and for the fact it went that way I am super happy. The ILM team led by Pietro Ponti and Ed Randolph were AMAZING! I say that not just as an employee hoping for a Christmas bonus but also with my independent hat as production supervisor. They more than hit the brief–they added so much value creatively. So many beautiful ideas and images they brought to the table. We’d start with brief & realism, then ILM would add their layer of creative pizazz and then we’d sprinkle Ridley touches on top for seasoning (flags, birds, embers etc.) as we learned what he liked for each sequence. ILM did Rome / outskirts, the Colosseum, opening battle & the final battle. The work went to them because we just knew they could be 100% relied upon, plus Nikki had just come off a really great experience on Abba Voyage with them.

We also went to Framestore where Christian Kaestner and Jeanne-Elise Prevost ran the show as VFX supe and producer. They were great, I know Christian from my time at Framestore – they were fantastic. Obviously FS has a creature reputation so they picked up the baboons and rhino. Due to the mysteries of finance we had to spend a bit more money with them for some tax reason or other so they also got the Styx underworld as a nice section of work.

James Fleming was supervisor at Ombrium; they were our overflow facility. They picked up niche little problems for us. A bespoke paint task here, a run of temps there, some smoke FX to glue this to this. Really great little Swiss army knife, as were also our in house team led by Jon Van Hoey Smith at Cheap Shot. I’d worked with Jon before and had been blown away by his problem solving and speed. The big VFX machine pipeline is essential, but sometimes a VFX ninja is the way to deal with a problem creatively and financially without compromise on either.

Then we had a little de-age work for the flashbacks. I had worked with SSVFX before to do this and they were amazing. Ed Bruce there has a great eye so we called them back and they nailed it.

Finally we also had Exceptional Minds do about 10 shots. They are an academy for people with autism launching careers in VFX and we were all super happy with the work. That was something Paramount asked us to do, and I’m pleased that they did.

I should also mention The Third Floor who did some amazing postviz for us. Hamilton Lewis, Pete McDonald and Jason Wen at various points led the charge. I wanted to go back to them because of my previous positive experience with them –and I was glad we did. When Ridley saw the rhino post viz he liked it so much he wanted to final it-honestly, we had to talk him out of it!

What is your role on set and how do you work with other departments?

Working with other depts is interesting on a show like this, it’s VFX heavy but it doesn’t feel VFX heavy as you prep and shoot. What do I mean by that? There’s so much practical build, so many cameras shooting at once (10 was normal for action, though 12 possible), such a big SFX team etc that it has momentum and that getting it in the can on the day is the focus. It’s easy to forget that we still owe this and that with VFX because there is so much there on the day. Every department has it’s job to do but most stop worrying on wrap, whereas in VFX that’s where a lot of the worrying still happens. So my job is (with the vfx team) is to beg, borrow, plead, negotiate whatever we can to get ourselves the best result. Asking camera to get us a clean plate of this or to scan this actor in this state or to knock back the practical smoke here etc. It’s all a series of negotiations and relationships where in general you’re asking for favours and giving not much back. Of course you can give back – you can say don’t worry about this or that we can fix it for you but those kind offerings are often assumed these days! The VFX team was great. Maddison Gannon was our PM and she is so capable and so lovely. Her team got things done. They knew who to talk to when. So I do my best on that front, working either via the team or direct to the other HODs. Then as the shoot is happening Nicky Walsh or Tom Carter-Drummond who ran the floor would be capturing all the data and organizing the wranglers. I’d be watching on the monitor one ear on Ridley’s radio one ear on VFX radio–and then when I saw trouble (or when Ridley called me) I’d run into Ridley’s trailer and plead my case as appropriate.

Can you walk us through the creative process behind the spectacular opening battle scene? What were the biggest challenges in bringing it to life?

There was no previz, not for this or for the whole show. But there was Ridley’s boards. As mentioned, he’s a great artist- good sense of perspective and visual story telling and that of course comes across in the boards. Then we add to that the plan was to shoot on the Kingdom of Heaven set in Morocco. So that means Ridley knew it (along with the Colosseum etc. obvs). So his boards could be accurate to the location. There’s a great start.

The KOH set was extended and adapted to our Numidia and gave a solid practical location with a lot in camera, so there’s a win. Obviously we needed to extend it and populate it for the wides but it’s something physical to work from so that’s great. There’s no ocean there of course so that was on us. Now you could flip the idea and try and shoot some/all of it at sea or in a tank but you’d probably have to replace the water anyway as the look wouldn’t be right, the amount of interactions from impacts and cg ships would demand it and then shooting would be very slow. Plus you’d owe a CG Numidia in the background, so better to take the solid win of KOH.

We did of course need some sort of ship there, so Neil Corbould’s SFX team rigged two 150ft Roman vessels that were constructed to these 20 axle multi directional transporter rigs. So in normal life they can be daisy chained to the length required and then used to transport giant things that need to be kept stable like turbine blades or bits of planes etc. So these things could move around the desert floor quickly (faster than the rest of the crew could move for sure) and Ridley could set his shot to taste- rather than relying on laying tracks and being constrained as such.

These two practical ships were then re-dressed in different configurations such as artillery, troop transport or siege tower and became our hero vessels as shots required. We added the hull, oars, sails, rigging, animated the siege towers when they needed to rise etc. Beyond the hero two ships the rest were added digitally. That said sometimes the hero ships themselves were fully VFX, but always using photography as a guide. For example sometimes the pitch and roll of the ship that Ridley wanted was more than the plate could deliver, or he wanted a different camera etc

One big challenge that became apparent in post was that the dusty desert sky and the geography of the KOH set meant the plates were often front lit or quite flat. Ridley’s very clever solution to this was to do full sky replacement, adding dark brooding clouds. It’s amazing how something front lit with a dark cloud behind it looks cool vs the original plate. That plus I’m sure it has some symbolic nature about the looming Roman menace.

How did you achieve the intense realism and scale of the battle, particularly with the large number of soldiers and complex choreography?

Ridley was good at keeping us grounded. He’d say not too many ships, keep it realistic. We need way more misses–more splashes than impacts after all it’s not a precision weapon, the catapult etc. So I think that kept us honest. Then to choreograph scale and distance we could add crowd, move the KOH set around, add ships etc as we owned them all digitally. We had TTF do a pass through very quickly and very early and that was great in ironing out the big ticket items broad strokes and giving editors the ballpark.

We did have a few amusing shots in the fort when it comes to choreography. I mean I can laugh now at least. Ridley was in such a hurry to shoot, he likes to move quickly. We had one where I think we may have had in a wide 15 crew of various sorts mixed in amongst then Roman soldier extras, not clean on the side but right in there. Meanwhile half the extras I think hadn’t heard action so were doing random things. That was fun.

What role did practical effects play in combination with CGI for the opening battle? How did you ensure a seamless blend between the two?

I think you back into the SFX as best you can so if there’s an explosion or a water splash that’s practical obviously you then attach a fireball or whatever appropriately to justify. On that score it’s kind of obvious. Then there are some which just won’t sell due to the trajectory or height of the impact and those you just need to remove.

Ridley is a big believer in organized chaos. What looks ridiculous on one camera can look great on the next and he has a lot of cameras, plus long takes so the practical effects are all part of the symphony. Also I’m sure it helps the actors get into the spirit of things. If there’s a specific thing I know will cause us an issue such as smoke then I’d put my case and normally he’d be very reasonable about it.

Were there any new or experimental techniques used to capture the intensity and chaos of the battle?

I don’t think so. I mean we tried to put in as much randomness as possible like fireballs rotating off axis, arrows bouncing off things etc I don’t think you pick them up individually but they all add up to a vibe. ILM were always adding cool little moments as well, the odd burning man running or collapsing siege tower. Dirt and water on the lens. All the old classics!

How did you handle the destruction and debris effects during the fight sequences, especially given the ancient Roman setting?

We used VFX smoke, ash and embers a lot both in the opening battle and in the Colosseum ship battle. They’re great battle texture, great energy, Ridley likes them and they glue the sequence together wonderfully. Also the smoke especially is great at directing the eye where you want, so popping a character out here, or flattening the image there when it gets too fussy or simply hiding a camera op.

The recreation of ancient Rome is breathtaking. How did you approach designing a historically accurate yet cinematic version of the city?

I think it ended more on the cinematic over historically accurate side of things! We did consult with a lovely professor of history about what was historically accurate and we tried to go that way, but very quickly we had to leave it behind. It became Ridley’s Rome. An example being the Colosseum, we adjusted the details to be correct, but it didn’t look like Gladiator and it didn’t look as cool. It’s a kit of parts very much dressed to camera, and that includes the Colosseum.

What were the most complex environments to build for the film, and how did you overcome the challenges of creating them?

This may not be the most complex but it’s a change from talking about Rome all the time, so I’ll say the Styx underworld sequence. It was shot on a stage in Malta with a small, dressed set. I think what was interesting there was Ridley was quite keen on the river being this liquid mercury look. The amount of viscosity and crustyness were a fun balance, getting the right amount of surface tension and movement to sell mercury but not T1000. I think it was also fun as we had such free range to sell each shot, we had some concepts to guide us but because it’s this fantasy location we could be creative about just dressing it to look good. Framestore got there really quickly and did a good job. In a different world on a different movie and if the sequence was a bit longer it would have been good for Stagecraft/ the volume. But that’s not Ridley’s thing.

How much of the ancient city was built as a physical set, and how much was extended or created entirely through visual effects?

It was a big set build, 1/3rd the height and maybe ¼th the span of the Colosseum. For Rome a large amount of fort Ricassoli was built up as Rome. For the larger buildings to 30 feet height or more. Then that set could be re-dressed for interior and exterior to play multiple locations.

Fort Ricasoli has all the Napoleonic tunnels which with a bit of dressing and modernity fix could feel very Roman. So we’d top that up and extend it. To be honest the bigger problem was populating it. We maxed out at 500 extras often way less. So things like the Colosseum would get, relatively speaking, a postage stamp of crowd. It was a real gamble working out where to place your crowd with so many cameras pointing in different directions. Of course where the practical crowd was missing we’d owe it, and often owe it layered behind fiddly roto etc…

Can you share insights into the use of digital matte paintings or virtual sets in recreating the grandeur of Rome?

Hmmm, not really. I mean there were dmps. At times Ridley would say things like, I’ll do you a favour and I’ll lock the camera–and I’d say actually please don’t lock it for me, I’d prefer if you move it it’s easier to sell–especially with the big vistas. Can’t beat a bit of parallax.

How did you leverage modern technology, like Unreal Engine or AI tools, to enhance the visual fidelity of ancient Rome?

We tried TTF’s Cyclops. It’s very cool and fun to use. But it just wasn’t quite immediately fast enough for the pace Ridley works at. Plus he’s got it in his mind anyway. Instead I resorted to taking stills from G1 when it came to the Colosseum at least and painting over them showing the vfx extension vs set plus the heights–then gave that to camera. Sometimes they’d be seduced by the sun peeking over to make a silhouette just cresting it but you’d have to say that can’t work there’s a whole Colosseum blocking it owed.

The movie features some impressive animal sequences, including monkeys, a rhinoceros, and sharks. How did you create these creatures, and what were the main challenges in making them realistic?

Well funny you ask. They’re all based on real ref, so a white rhino, a sand tiger shark (admittedly with a Tiger shark’s more impressive dorsal fin attached) and then of course a baboon with alopecia.

So early on Ridley saw this nature footage of a baboon with alopecia, (ie hairless) and fell in love with it. So that’s our hero. He looks a bit dog-like or a bit alien, and I think that’s what Ridley liked. Anyway we matched him and then it was all about the lean ribs, the muscle tension and twitches. Any chance I could get I was encouraging Christian and his team to load up on those to get us away from rubbery-and they did a great job.

Were these animals entirely CGI, or did you incorporate practical elements to bring them to life?

They’re all entirely CG. That said we did everything we could to help the sell of the physical and emotional performances of both creatures and actors. So the baboons had the smallest stuntmen that could be found (they still weren’t that small) playing them. They wrestled with Lucius and friends and scampered about the arena. Then Framestore had the unenviable task of removing them via CG body parts, creative background plate surgery and brute force paintwork before replacing them with keyframe animation baboons.

We also had a proxy baboon torso that could be puppeteered for the close ups. Again this was fully replaced but at least it was closer to the correct size so was less of a pain.

Can you explain the techniques used to animate the rhinoceros during the battle scenes, especially in terms of weight and movement?

The practical rhino on the day was an amazing SFX rig on wheels made by Neil Corbould and team. It could be radio controlled to drive around the Colosseum at speed. So that gave lighting ref, eyelines and performance etc. On it’s back was out actor/stuntie on a saddle. It would buck up and down as it went mimicking a rhino’s galloping gait. Vital to get the physical sell into the actor. It worked pretty well, Framestore backed into it and in general we kept the rider and saddle. That said sometimes there just wasn’t enough movement so his lower half or all of him had to go CG.

Then after that FS would plug in whatever they do to get the lovely fat, muscle, skin slide and wobble. It just looked amazing out of the box. The rhino went down very smoothly.

The shark scenes are quite intense. How did you ensure that these sequences felt both threatening and realistic?

The sharks were also about interaction, so the stunties were pulled on a jerk rig to give the appropriate shark vector. A little bit of help from us to increase the speed then pop in the shark and some bubbles. Compared to the baboons they were a walk in the park.

What references or inspirations did you draw from to make the animals feel authentic to the ancient Roman period?

We made sure they were all scarred and imperfect. They have all been in the wars in one way or another. Not specifically Roman I’m sure to have injuries but we definitely would have missed them if they weren’t there.

Were there any unexpected technical or creative challenges encountered during the production?

Yes. People had told me before we’d be picking up camera paint out and roto but I had no idea how much. I don’t think anyone who didn’t work on it would understand. Maybe the Napoleon crew. Think we should form a mutual support group.

Were there any memorable moments or scenes from the series that you found particularly rewarding or challenging to work on from a visual effects standpoint?

The final battle, where the two armies face off outside Rome. That was split between Sussex (UK) and Malta, plus 90% of the armies are CG. The decision to put in armies was a decision taken after the fact. The efforts required to unify the two locations were massive. Sussex was just a grassy lush field. Looked nothing like Malta physically or in terms of the light quality. So much work just to be not wrong! I’ll put that in the challenging camp.

Looking back on the project, what aspects of the visual effects are you most proud of?

I like the Colosseum Naval battle. There are some spectacular shots in there. I mean I like all the work of course but I’ve not mentioned it in the interview yet–and it was a bit special.

How long have you worked on this show?

2 years all in.

What’s the VFX shots count?

Nearly 1200.

What is your next project?

I’m not officially on it yet so can’t say.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

ILM: Dedicated page about Gladiator II on ILM website.

Framestore: Dedicated page about Gladiator II on Framestore website.

SSVFX: Dedicated page about Gladiator II on SSVFX website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2024