After KNOWING, GODS OF EGYPT marks the second collaboration between Eric Durst and director Alex Proyas. Before that he had supervised the visual effects of a large number of movies such as BATMAN FOREVER BATMAN & ROBIN, SPIDER-MAN 2 or SNOWPIERCER.

What is your background?

I grew up in Arkansas and my dad was a professor of art, which I think set me on the path to being an artist. It was an interesting time, because my dad had built this Art Center at the University where he taught, and what was unique about it was that it housed all the arts. There was a school of architecture, as well as a school of music, dance, painting, sculpture and theater all housed under one roof. It was a great environment to be in when I was a kid, because there were so many things going on and all the arts represented. It was based on the Bauhaus, a very famous German school of the 1930s that had the philosophy that since all the arts were related, they needed to be taught together.

Growing up around all the arts was confusing also, because even though I knew I wanted to be an artist, I wasn’t really sure which area to specialize in. So I spent a couple of years in architecture school, because I just loved great buildings and wonderful houses and wanted to be part of that. Then the reality of what architecture really was, and that only a handful of people got to do that kind of thing swayed me to go into painting, so I did that for another year. Then one night I was watching television, and there is a documentary on Cal arts. That school seem to have all the same things that I had grown up with in Arkansas, all the arts put together in one place, it seemed like the perfect place to complete my college career.

So I applied to the school and fortunately got in, this time with a major in photography. The first day I was there, I met some people who were studying animation, so I went into the animation room and sat down, really just looking around. Jules Engle, who was the great teacher of that department, came over and I guess assumed that I was a new animation student, so he gave me a stack of paper and pencil and said “okay there you go start drawing and make a film”, and that’s how it started.

I loved experimental animation, and creating movement that blended abstract as well as figurative material, so I did a number of films like that. They were pretty successful on the film festival front, so I was able to support myself with various grants from the government and corporations which allowed artists to do their work. After graduation I lived in New York City and continued in the independent animation world, while also dabbling in the commercials with animations for public television and commercials.

I moved back to Los Angeles, and met a number of people who were in the visual effects world, which seemed like it was a great blending of both live-action photography and animation, so I was really excited by the field. I spent a number of years at DreamQuest Images, a visual effects house, mainly directing commercials, but I always wanted to work in features.

The first big film I had a chance to work on as a visual effects supervisor, was BATMAN FOREVER in 1995. It was a great break, because I was in charge of Gotham City, which at that time was all miniature work, I was just amazed at the scale of everything, and the incredible talent that you’re surrounded with a feature film. It was a terrific way to begin on the feature side. From there on is been pretty nonstop, leading up to where we are today.

How did you get involved on this show?

In early March 2013, I received a call from Kathy Chasen-Hay, who heads up Visual Effects for Lionsgate. She told me that they had a massive production that was in development, and they were looking at producing it down in Australia. It was being directed by Alex Proyas, who I had worked with before in 2008 on KNOWING, so it seemed like a good fit. I received a number of concept illustrations and a script, and a few weeks later we were off to the races when I flew down to Sydney to meet with Alex to discuss the project and start working out the details of how to make it happen.

How was your collaboration with director Alex Proyas?

It really helped that I had worked with Alex before, and I think that’s true with all projects where you’re working with people you have experience with, because there’s a shorthand that happens in your communication, and you also know what to expect. Alex loves visual effects and has a complete trust in what is possible, so he was always pushing, always asking for a bit more than what we thought we were capable of… and that’s the role of the director, to really push everything to its limits.

What was his approach about the visual effects?

Alex feels that visual effects can do about anything. So in this film, which was so virtual, so large in its vision and what it needed to accomplish, visual effects had to really build most of the world that was being shown in the film. Because the visual effects it were such a the key component in everything, Alex trusted us to deliver, and focused most of his attention on the acting and storytelling.

Can you describe one of your typical days on-set and then during the post?

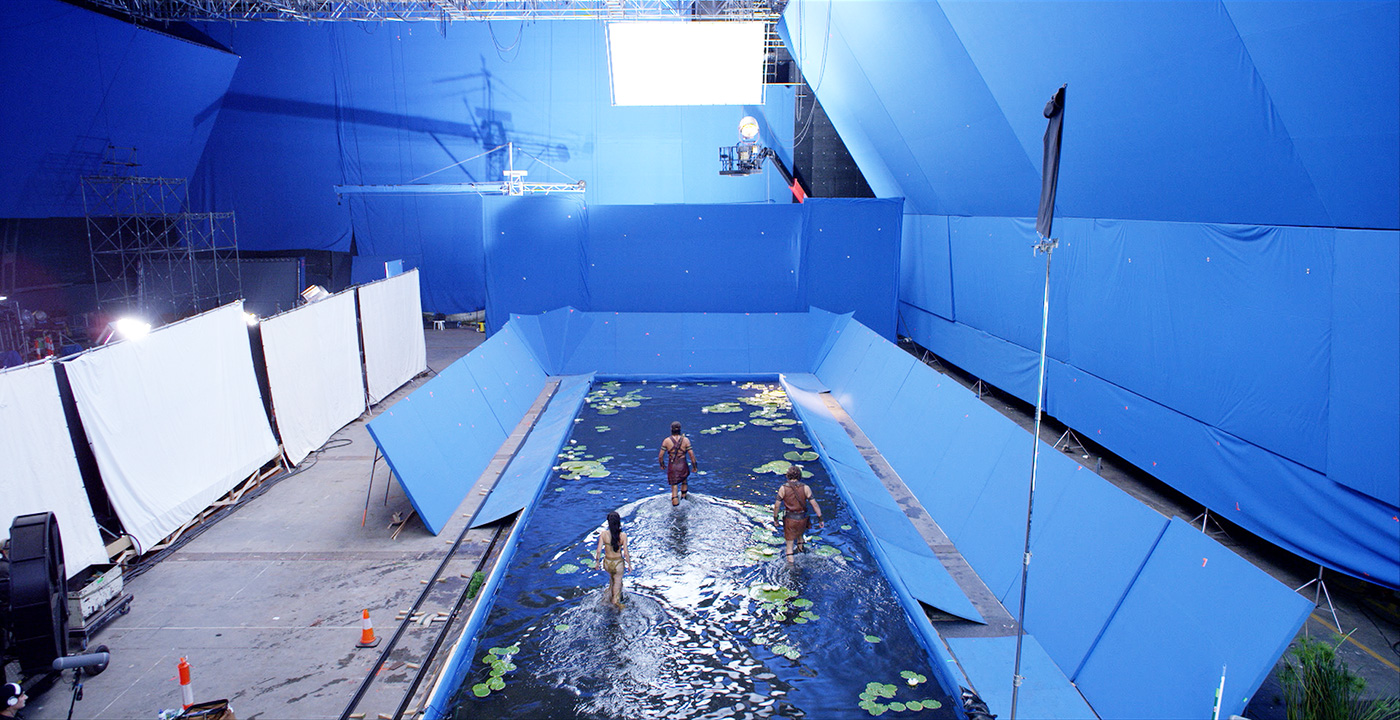

There were no down days for VFX on this production. We had two crews shooting simultaneously on several stages at the Fox lot in Sydney for 16 weeks. While we were shooting on one stage, often another stage was being prepped for the next day’s work. Derek Wentworth, who was the 2nd unit VFX supervisor, handled one of the crews, while I would be on set at all times covering the 1st unit work.

We started every day with a walk through of the day’s action with all the actors. Because basically ever shot in the film was a VFX shot, there would often be many questions that would come up up during this period that would ripple out to the work of the day. During photography, often times even a slight change in camera angle from what was planned during the Pre-Vis process would have an impact in what would be needed, since most everything beyond the actors and their immediate set pieces was all VFX, so you had to be very heads-up at all times. Basically it was nonstop for 10-12 hours a day.

I like to have the VFX supervisor or a representative from each of the facilities there when we’re shooting their scenes for many reasons, mainly so they can become introduced and fully integrated into the production during the photographic phase, but also so they can make sure that they come away with all the elements that they need. Often times, what happens is we come up short because of time or the resources needed to complete the wish list, so they’re part of the conversation of deriving with solutions or what is absolutely necessary and what can be cheated.

Because we were in Sydney, it was a bit difficult to make the journey, but Andy Morley from Cinesite, Robert Bock from Rodeo and Matt Jacobs and Tom “Gibby” Gibbons from Tippett were able to be there while their company’s plates were being photographed. It was easier for Andrew Hellen and Julian Dempsey from Iloura and Tim Crosbie from Rising Sun to be present as they were already in Australia.

This show has massive VFX work including CG characters and lots of CG sets. How did you prepare a show like this?

First of all, hats off to Owen Paterson, the great Production Designer and his immensely talented team of artists. They really laid down the framework for everything, with intricate designs for all the creatures and environments. So we were starting from a strong foundation. As solid as that visual foundation is, when things start to move, all kinds of adjustments need to be put in place to keep the original vision intact. I’ve been through this many many times, but it’s always amazing the differences between a still image and moving one. Two different universes, and exponential needs for the latter.

Because we had previs for essentially the entire film, we had a good idea of how the virtual backgrounds and scenes worked in the edit, so even though the live-action was essentially actors against blue, there was extremely good guidance.

There was a huge mix of so many different kinds of visual effects in this show, from characters to massive CG environments, water, lots of atmospherics, really everything in the book, so a big part of the show’s preparation was finding and putting the right team of visual effects players and companies in place to achieve all the work we had on our plate. Because of the Australian production incentives, we needed to have a majority of the work accomplished by Australian visual effects companies. VFX producer Jack Geist and I spoke to many of the worlds VFX companies, and put together a roster of what we felt was a good combination for the needs of the show.

Iloura, who have offices in Melbourne and Sydney, Rising Sun Pictures in Adelaide and Fin out of Sydney handled the work from the Australian side. Raynault and Rodeo FX from Montreal, Cinesite in London, UPP in Prague, Tippett in Berkeley and Comen VFX in LA represented the other half of the world. We also had an In House team that worked out of our VFX Department in Sydney, and Derek Wentworth, after his work on 2nd Unit, lead a compositing team in Montreal.

Can you tell us more about the previz process?

Because we were working with partial sets, to truly understand the action, it was essential to Previs the entire production. Alex also wanted to direct actors as a foundation for the Previs of the film, rather than rely entirely on animators to develop the story.

I had known Ron Frankel for some time and his company Proof, and was very interested in working with Ron and his team. Proof, who is an LA company, was also set up as an Australian Corporation, so they were set up to hire out the team of artists and start any time. David Peers, who is an immensely talented director and storyteller, was hired as the Previs Supervisor. This was a great decision, because David was able to always keep the storytelling in central focus as he journeyed with his team through all the worlds created in the film.

We created a stage that had a grid on the floor, which was very much like a chess board. We had three witness cameras that captured the action from various angles of everything that occurred on the stage. Alex would block action with actors, and go through the scenes, similar to what you would do in a stage play. This became the foundation reference for the animators to use as they develop the sequences.

The thirty person team worked for about 20 weeks before we started principal photography, then continued for many weeks after, refining upcoming sequences, providing a framework for everyone.

With so many blue screens, how did you help the actors and the crew to imagine what will come many months later?

The previs was the biggest asset we had, because it was very true to the framing and final result of the film. This gave everyone the best idea of what was later to come. This helped not only the crew and everyone setting up the scene, but also the actors. Contributing to this, was the SolidTrack system that enabled us, in real time, to composite backgrounds into the live-action shots, furthering the preview of the final composite. The SolidTrack system would track every movement of the camera in relation to the stage background, apply this through the computer to the 3D backgrounds derived from the assets built for the Previs, and provide us foreground and background elements that fit together.

What was the most complicated sequence to shoot and to create in post?

That’s a difficult question to answer, because there were so many shots in the movie, and many of them were quite complex. So to have one singled out is something that I really can’t do.

One of the most difficult parts of the process though, was the fact that a large number of the shots, 721 to be exact, needed to be shared between facilities. The shared shots were usually between 2 or 3 houses, but in some instances, it would need to filter through 5 and in one case, 6 houses. So the logistics of this, mixed in with the overall show, which had 2550 shots, became pretty mind-boggling.

Can you tell us more about your collaboration with Alex Proyas and his team to design and create the various Gods, creatures and environments?

In the early stages of production, and this was now 3 years ago, we had a small team of conceptual artists developing the initial designs in Sydney, working with Ian Gracie, who was the lead Art Director. We would put together the images, show Alex, get feedback and proceed from there. But we could only go so far, because the production had not been green lit at the time.

When we received the go ahead, and Owen Paterson came on board, everything started to kick in. Owen had also worked with Alex previously, so he had a good idea of Alex’s visual intentions.

There was a lot of back and forth between visual effects and the art department, not only in just the final look of the environments, but in what would be needed for the sets. Because the art department was designing partial sets, there is always the question of how much to build. Everything gets reflected in time and money, so you never want to build more than you need to. But also, you always want to build enough so the actors and those photographing the scene, have the essence of the environment, so there is something to photograph, and the actors have enough tangibility to work in.

The Gods have a different size of the humans. How did you manage this difference?

The Gods were one and a half times larger than the Mortals, so a 9 foot God, would tower over a 6 foot mortal. I knew early on that this would be the most ubiquitous effect in the film, and how we approached this needed to be fluid and easy. We started with a number of tests, seeing what we could do by just scaling and shrinking the actors in post, with the actors focusing on targets either higher or lower, so the eyes would be correct after the scaling. Often times, we would use platforms to help create the effect, scaling the actor down from the top. In cases when a God was holding on to a mortal, the God would be placed on a smaller platform and scaled up and down from the point of contact.

Because you’re filming actors who are next to and often touching with each other, all kinds of obstructions would occur, which resulted in holes as you shrink or scale the actors. To help solve this problem, with Director of Photography, Pete Menzies Jr., we developed a side-by-side camera rig, similar to a stereo rig but with the cameras much further apart. This enabled us to have a different angle on the actors, so we could use that photography to paint back and repair any missing areas.

Using the dual camera rig, we were also able to control depth of field by keeping foreground and background actors both in sharp focus, assigning a camera for each actor, and keeping the focus sharp on each. This technique really helped when we had a foreground actor who was God size. By having one camera on the background actor in sharp focus, and the other camera keeping the God in sharp focus, we could combine the two and give a much more convincing scale to the shot.

We also used a lot of forced perspective, that would be enhanced by scaling, but the lands helped us in many instances. Also though, it hurt in many situations as well. For example if a mortal was in the foreground, and God was in the background, the force perspective worked totally against us. In cases like this you would often have to scale the God up to sometimes 2 1/2 times, rather than a normal one and a half times, just to even hint that they were different sizes.

We also had dual motion control camera rigs available throughout the show, where we shot actors on two separate stages. The motion control rigs were set up, so one camera would drive the action, while the other camera was a slave, scaling and speed and distance so it made the actors on one stage appear larger than those of the other.

Can you explain in detail about the transformations of the Gods into mythical beasts?

In the film, Gods could change form from their humanlike appearance to a creature. These transformations would usually occur at peak moments, and come out as latent powers that dwelled with inside the Gods, and they would take on these forms as needed.

On the set, we would have the actor perform the action of changing from one character to the other, contorting as they went through the motion. Their action was then match moved, and applied to the CG character as the transformation occurred.

What was the most complicated CG characters or creatures to create and why?

The most difficult creature was the Falcon, the other form of the God Horus. The Falcon, because it has a beak, doesn’t really have very much form of expression. There are scenes where Horace speaks in his Falcon form, but talking with the beak looks really strange. So to get around this, we had the head transformed back to the actor, while retaining the body of the Falcon. Another challenging part of the Falcon was his skin, which was a metallic silver and gold. As he would move through different environments, the light and reflections would so radically change his look, that the artists at Rising Sun consistently needed to adjust the reflectivity, so we could retain the massive amount of detail that was in the surface of the Falcon’s feathers and body. Often times the reflections be so overpowering, that you got no sense of detail in the creature, even though it is all there, and you needed that detail at all times to make the creature look correct.

How did you approach the animation of the CG characters?

In many instances, the animation of the characters was driven by performances from actors and stunt performers. Anubis, who ushers souls into the afterlife, was played by Goran Kleut. Goren would perform the scene with other actors, in a garment with tracking markers, and Iloura would use that as the foundation for the animation of the creature. The same type of technique was used for the Bull Gods, in their fight with Horus. In this scene, stunt performers fought with Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, and their performances drove the action of their animated counterparts.

For the Sphinx, this creature was animated entirely by Tippet Studios, and rendered along with sand simulations by Rising Sun Pictures. The Falcon and the God Set’s form as a Jackal, were also animated by Tippet Studios and rendered by Rising Sun.

Apophis, who is a giant black cloud like creature who brings chaos, was created by Rising Sun Pictures using intricate and incredibly complex particle simulations.

Can you tell us more about the various locations and environments and how you created them?

We had many many environments for this film, from lush green forests to dry desert sequences. All the locations were created in CG. Many shots utilized photographic projections.

Some environments used photographic elements, for instance for the sequence where our heroes are walking through the windy desert, Victor Muller from UPP in Prague flew down to Morocco and spent several days photographing the deserts of that country, so he could get the exact look of the desert sand in the evening light.

The Cobra sequence, which also took place in a large desert environment, was created by Iloura in their Melbourne studio, led by Julian Dempsey. This world was created all in CG, with digital matte painting backgrounds.

Set’s Pyramid, which forms and disappears in front of Bek as he tries to run up stairs which continually evolves, was entirely simulated, again by Iloura’s Melbourne office.

Ra’s Boat, which is located high above the Earth, was created at Rodeo, led by Arnaud Brisebois. The Sea of Creation, an ether material that surrounds the boat was generated through particle simulations by Rodeo.

The Nephthys’ Stronghold sequence, created by Cinesite London, with Andy Morley leading the teams there, was all CG driven with digital armies fighting protecting the main castle.

How did you split the work amongst the VFX studios?

Iloura in Sydney and Melbourne did about 1000 shots on the show, so they were the largest company in terms of workload and number of shots. There was a vast variety in types of shots in the show, and because Iloura has strong teams that specialize character animation, simulation effects and environments, they were able to service this large number of shots and do superb work.

Rising Sun Pictures is incredibly strong in effects and simulations, along with environments, so they did many types of shots on the show, including Apophis, an entirely sim based creature and the sand based Sphinx creature and his environment. RSP also built the models for Heliopolis and the Palace Coronation area.

Rodeo in Montreal is very strong with hard surface subject material, and did an amazing job in creating Ra’s Boat, which is made from crystal and gold, so there was an remarkable amount of detail and refractive lighting went in to sequences with this vessel.

Raynault in Montreal is masterful in matte painting techniques and environments, so they did an incredible job with the opening helicopter shot into Heliopolis, using projection techniques, along with creating the Land of the Dead sequences.

UPP from Prague is very strong in creating beautiful environments, along with a wide range of other strengths at there studio as well. For the show, they did a variety of environments, including the Marsh sequence, which blends water photographed on stage, with CG water extensions and a forrest, with vines and trees containing enormous complexity.

Cinesite in London, manages a large palette, with the capability to deliver a large number of shots with environments, crowd simulation and character work. For the show they did an impressively large number of shots in the Coronation sequence, along with battle sequences and a large sequence where Set returns and rallies his army.

Tippett Studios is a great animation studio and we utilized their animation skills mainly on the Sphinx, Jackel and Falcon creatures, but they also did a shot where Hathor is swept into a vortex filled with Demons.

Can you tell us in details about your collaboration with the various VFX supervisors?

The VFX Supervisors at each of the facilities are the key component in all the work that you do, and the quality of that relationship determines how well all the work that you accomplish ends up. So because of this, it’s important that you really know each other well. Usually this means that you go to the facility in person and meet each other, or they come to you at the studio while you’re shooting. All that’s really important. But the interesting thing is, because we’re working all over the world, oftentimes that’s not possible, so we sometimes have to meet people via Skype. And the fascinating part of this, is that when the person on the other line and you are in sync, that translates across, even if it’s in a crude system, like talking through Skype. So a lot of people that I work with, and I work well with, I’ve never really met in person, because that thread of understanding comes through.

We had great supervisors on the show, every one of them, and regardless of the mediums we had to speak through, whether they were there in person, or on an iPhone looking at a crude picture of an animation test on a monitor from London, it all worked.

These various studios are based all around the world. How did you follow their work progress?

We would have cineSync / Skype review sessions every week for the first part of post production, then accelerate the number of sessions as we got further along and closer to the deadline. They would usually be with Jack Geist and myself along with the supervisor of the facility and their team. Jack and I would meet with Alex once a week, then followed by more and more meetings as we progressed in the schedule.

We kept this very consistent, and on the same day in same time with every company, which really helped get everyone into a rhythm.

We had a screening room in our office complex, so with Alex we were able to review shots as they came in on the big screen, and then we would distribute notes to all the facilities. As we got further along and the shots and sequences became more developed, and time became more pressed, we would have combined reviews with Alex and the facilities on the other line as we viewed everything on the large screen.

Every session was recorded with Screenflow, so we could go back and review things if notes were unclear.

What was the main challenge on this show?

The biggest challenge on the show was staying consistent, and by that I don’t always mean visually, which is obviously extremely important. For me it was how to maintain this fast pace marathon over a period of two years, and not get tired or wiped out by it at the end. And be stronger at the end than when you started. Really that’s the only way to do this kind of thing well and perform, because if a project’s massive demands weigh you down, you lose your objectivity, and really let all your teammates down.

I’ve been on so many shows, especially when I started in the business, where at the end of it I would be so depleted, I have to take several months off just to get my head screwed on again. This was a show that could’ve done that, but a lot of us didn’t want to go down that rabbit hole again, so we really challenge ourselves and got into extreme fitness routines, had the right diet, did all the things that you need to do to survive these kind of projects, and I think it really paid off.

What do you keep from this experience?

I received so much from this experience. The first thing you realize is the enormity of talent that you are surrounded by every day. It’s really humbling. What you hope to do is give guidance that’s strong enough so everyone’s going in the right direction, but at the same time leave enough of an opening, so the artists doing the work can add to that interpretation, and make the work better than anyone could ever anticipate.

Along with this, you get to experience just how much a team of people can produce, using small steps every day, which all add up in the end to an unfathomable amount of work.

How long have you worked on this film?

I worked on the show a little under three years. It started in early March 2013 with the early development and ended in late January 2016, with the final color correction. The film was in the theaters in late February.

How many shots have you done?

There were 2,550 visual effects shots in the film. 721 of the shots were multi-facility shots with anywhere from 2 to 6 houses working on each shot.

What was the size of your team?

Our VFX team in Sydney was really small for a show of this size. Along with Jack Geist, the VFX Producer, and Jodie Weston, the VFX Production Manager, we had a team that varied depending on what stage we were in, but anywhere from 8 to 12 people,

A big thanks for your time.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2016

Wonderful, love the way he underlines the teamwork and the individual discipline to rhythmic working and to poison rest and diet to run such a marathon.

I’m thinking if Gods of Egypt as is had been released in 2010, it would have been a big deal and money maker. I’m also thinking if Marvel studies had made it–not much would have been different.

Anyone have ideas of what could have been done differently to make it more commercially successful?

FYI I also loved Jupiter Ascending, the effects film from 2015 receiving very similar reception to Gods.