Earlier this month, Bryan Hirota explained in detail the work done by Scanline VFX on Zack Snyder’s Justice League. He’s back to tell us about the epic confrontation between titans!

Chris Mulcaster started his career in visual effects in 2010. He joined Scanline VFX in 2013 and has worked on a wide range of projects including Game of Thrones, Aquaman, Spider-Man: Far From Home and Zack Snyder’s Justice League.

Jim Su has over 20 years of experience in visual effects. He has worked on several shows such as The Three Musketeers, 300: Rise of an Empire, Star Trek Beyond and Ant-Man and the Wasp.

Prior to joining Scanline VFX, Kishore Singh worked at numerous studios such as Framestore, ILM and MPC. He has worked on projects like Gravity, Warcraft, Black Panther and The Meg.

Jonathan Freisler has been working in visual effects for over 10 years. He has worked on projects like Ted, After Earth, Mad Max: Fury Road and Tomb Raider.

With over 20 years of experience in visual effects, Eric Petey, has worked on many films such as Transformers, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, Rampage and Captain Marvel.

How did you feel bringing this epic confrontation between two iconic movie monsters to life?

Bryan Hirota: I was quite excited at the opportunity to work on this film. The original King Kong vs. Godzilla was one of my favorite films when I was young as it was shown on afternoon television. When it looked like I was going to get a chance to contribute to a remake of a classic kaiju film, I felt quite lucky.

How was this new collaboration with VFX Supervisor John ‘D.J.’ DesJardin?

Bryan Hirota: DJ and I often look for opportunities to collaborate together. I was finishing up our work on Aquaman when he was hired to supervise Godzilla vs. Kong. They wanted to make sure Scanline could do big creatures so Stephan Trojanksy and myself met with DJ/Tamara and picked some shots to do as a test. We took the Kong asset from Kong: Skull Island as a starting point and bulked him up and aged him to reflect the amount of time that had passed from when Skull Island was set. They liked it so much they had us continue to develop the hero asset.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

Bryan Hirota: I’ve worked with both VFX Producers Julie Orosz and Ryan Flick on a number of projects. Both of them were instrumental in keeping the show run smoothly as the facility needed to switch our worldwide operations to a work from home operation during the pandemic. They deserve a lot of credit for keeping the teams in all of our offices informed and moving forward with the needs of the show.

How did you split the work among the Scanline VFX offices?

Bryan Hirota: The company has grown to have offices in a number of locations now. Luckily everyone shares the same infrastructure so we don’t have to worry about transferring assets and so on between offices. An artist can immediately pick up work created in one office in another.

What are the sequences made at Scanline VFX?

Bryan Hirota: We developed what we called “old man Kong” asset that was shared with Weta and MPC for their sequences. The sequences we worked on were the initial attack on Pensacola by Godzilla, Kong on the transport ship including his fight with Godzilla at sea, Mecha Godzilla in the arena, Mecha Godzilla’s battle with Godzilla, and the team up with Kong and Godzilla against Mecha Godzilla in Hong Kong. We also did the shots where the two remaining titans acknowledged each other and went their own ways.

Can you explain in detail about the design and creation of Kong?

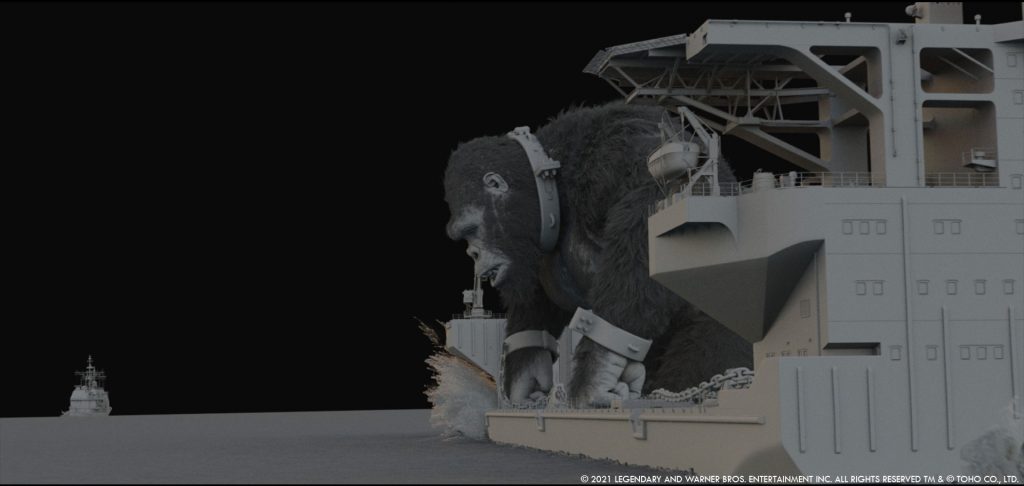

Chris Mulcaster: At the beginning of the project we took a trip to the LA Zoo to study the gorillas and capture valuable photo reference and videos that we used in our development. As a base, we started with the Kong asset from Skull Island who was an adolescent and much smaller. Our model lead, Damien Lam, went through several model concepts and paintings before re-sculpting Kong to show the age deterioration and battle scars that he had incurred in the 50 years that had elapsed. In that time Kong has also substantially bulked up, for the impressive weight and muscle mass on Kong, we studied veteran body builders and how a strong physique degrades over time.

In the ocean battle, Kong stood at around 300ft tall which is 3-4 times larger than he was in Skull Island and in our Hong Kong sequences, we had to scale him up to over 500 feet.

We spent a lot of time developing the fur for Kong and introducing aging grey and white hairs using the V-RayHairNext material. Once we had established the base dry look, Changmin Han, who created the textures and shading for Kong, also developed a number of other looks including various stages of wetness, ‘oily Kong’ (where he is drenched in Mecha’s mechanical oil) and a dusty version. This was further supplemented by our effects team who also simulated small building debris and dust falling from Kong’s fur as he interacts with the buildings around him.

How did you develop the body muscle system for Kong?

Jim Su: There were two setups, one using Ziva VFX which is a physics-based muscle simulation, the other was using a procedural jiggle rig. The jiggle rig takes advantage of Maya’s GPU deformers and has real-time playback. Most of the shots run through a jiggle pass since the turnaround is quick and results can be rapidly iterated. The jiggle setup is anatomical, respecting muscle insertions and attachments. Any shots that required more hero muscle simulations were run through Ziva. The setup requires modeling the skeleton, muscles and a tissue with thickness consisting of the fascia and skin. There is a muscle simulation pass, and the fascia and skin combined simulation pass.

Can you tell us more about the fur and groom work?

Jim Su/Kishore Singh: The groom was done using XGen core in Maya by our groom lead Tarkan Sarim. The fur system and simulation setup are run with Maya’s nHair. As the lead vendor on the show, we were tasked with creating the master version of the groom and provided the groom data to the other studios to match our version.

Due to the complexity of the groom, we ran into technical challenges and limitations. To overcome these, we experimented with splitting the groom up into 10 smaller chunks. This resulted in quicker hair generation and previewing times within the viewport. We also utilized the viewport render features in Maya’s Viewport 2.0 which provides full shading for fur as well as lighting and shadow previews. This gave us a very close representation of how the rendered fur would look without us having to render time consuming tests, increasing our efficiency and iterative abilities greatly.

We completely overhauled our hair system to allow for interactive manipulation of the guide hairs, and created a multi-shot hair simulation tool. All fur elements were created by sculpting guide curves. At the beginning to block things out we would start with a smaller amount of guide curves and try to push the groom to about 70% completion. We were able to change the parameters of all grooming attributes on the fly without having to redo everything like is the case with a purely sculpting based grooming workflow. Although we were using a procedural approach, we were still able to utilize some of the purely sculpting based grooming tool features to add finer details when required.

Every individual strand of hair was cached out and rendered in 3ds Max, made possible with due to the creation of a procedural tool that writes out all the XGen hairs into a custom alembic file for each frame that we referred to as a hair cache. Once the hair cache is written out it can then be loaded into 3ds Max as a V-Ray proxy and used for rendering.

Kong is really emotional in some sequences. Can you elaborate on this?

Jim Su: We established a new facial mocap system at Scanline for this movie. We had our Animation Supervisor, Eric Petey, act out a lot of the hero performances at our in-house mocap stage in an Optitrack Motive suit with a Faceware Mark III head mounted camera. The matchmove department would turn the video footage into keyframes using Faceware Analyzer and Retargeter. Animation would add creative embellishment to the facial performance. A new facial rigging system was designed to handle the facial nuance such as non-linear wrinkles and interconnecting of facial shapes. Even with the amount of facial shapes and complexity of the rig, it had real-time playback by taking advantage of Maya’s Parallel Evaluation and GPU deformation. We also obtained the Chimp FACS courtesy of the University of Portsmouth to understand the differences between human and chimpanzee faces.

Can you tell us more about Kong’s eye work?

Jim Su: We rebuilt our eye model for Kong’s eye, introducing the conjunctiva on the eyeball within our rigging and lookdev workflow. Introducing this extra layer to the surface of the eye meant we were able to get proper coloration and more realism to our eye model. We also accurately replicated the shape of the cornea, how it refracts light and interacts with the iris so the iris appeared correctly. We had full control of the meniscus and therefore we were able to control the mix of oil and water that sits on the surface of the eye.

Let’s talk about the other titan, Godzilla. How did you enhance the model from the previous movie?

Bryan Hirota: Godzilla was not modified from Godzilla: King of the Monsters. We needed to adapt the asset to work in our pipeline as we had not worked on that film, but from a visual standpoint to the audience, it was unchanged. One thing we added to Godzilla was an enhanced interior physiology so that when he was struck by Mecha Godzilla and the blue genetic energy coursed through his body, you would get glimpses of his skeletal and vascular system seen through the skin.

How did you create and animate the famous atomic breath of Godzilla?

Jono Freisler: For the atomic breath we grabbed as much reference as we could find from existing movies. DJ pointed us towards shots favored by the director because over the years, the atomic breath had slightly different flavors between movies. We actually tracked the reference to get the right size for Godzilla, which then paved the way for us to match the look as closely as possible, matching color, speed, spread and detail. Then we could do a side by side comparison with the same camera move with a 1:1 line-up to match the look. The direction of the beam evolved slightly in this movie, it became a bit more focused and faster to give Godzilla more intimidation and threat.

What was the main challenge with Mecha Godzilla?

Bryan Hirota: The main challenges with Mecha Godzilla was adapting the approved model from the art department, finding ways to stay true to the design but enabling the articulation in the joints to allow full movement without interpenetration. We also added additional details both on the surface and the internals to provide both structure and scale. Lastly, we developed and integrated all of the various bespoke weapons and attack systems that Mecha used.

How does the massive size of these titans affect your work?

Bryan Hirota: One of the challenges in dealing with creatures of this size is making sure you help support that massive physicality with additional simulations. Whether that’s with fluid simulations, large-scale destruction or their interactions with mist, smoke or dust. These creatures in particular are so large that they required believable interactions with the world around them.

What kind of references and influences did you receive for their fights?

Eric Petey: The best source of reference for the fights was, in my opinion, the previous two films in the series. Through watching them, we could see what had worked well, and where it was possible to try something new – to turn things up a notch. It was also very helpful to hear Adam Wingard’s and Legendary’s thoughts about key moments of the action in those films.

Of course, we also received previs for our fight sequences, which served as a great window into where the director’s vision was headed. During the course of production, we had to re-imagine large portions of the battles in a postvis process. Working with Bryan Hirota, we distilled what was successful about the previs, before deliberately going a bit crazy on new choreography using influences ranging from 80’s action films, to Muay Thai fighters.

Can you tell us more about the animation differences between natural titans (Godzilla, Kong) and the mechanical titan (Mecha Godzilla)?

Eric Petey: We had to approach the animation of the three titans quite differently. The two “flesh and bone” titans were more bound to both the expectation of what Kong and Godzilla have always been, and the fact that they are living creatures. Kong, in particular, is still a gorilla; even if he is over four hundred feet tall, we still needed to ground his animation in what is very familiar to most people. With that in mind, we used Scanline’s in-house motion capture stage to generate much of Kong’s motion and facial animation. Unsurprisingly there are many types of action, particularly in a fight sequence, which are impossible to capture without broken bones and lawsuits. Luckily there is no shortage of online videos featuring people doing insane things.

Godzilla’s animation, though not possible to motion capture, is well established with over sixty years of material to look back on. The challenges with his animation were related more to his anatomy. Finding ways around the limitations of his relatively short arms, and his back full of long spiky plates, was often a huge challenge.

Animating Mecha Godzilla was very exciting for the team as he is not established with fans of the recent films. Given his larger size, and his non-biological construction, we could immediately give him a strength, speed, and flexibility advantage, which opened exciting possibilities we didn’t have with the other titans. Mecha is also a sort of cross between a Transformer and a Bond car, so there was always the potential to redirect the action with a new surprise weapon or ability.

How did you create the various ships for the ocean battle?

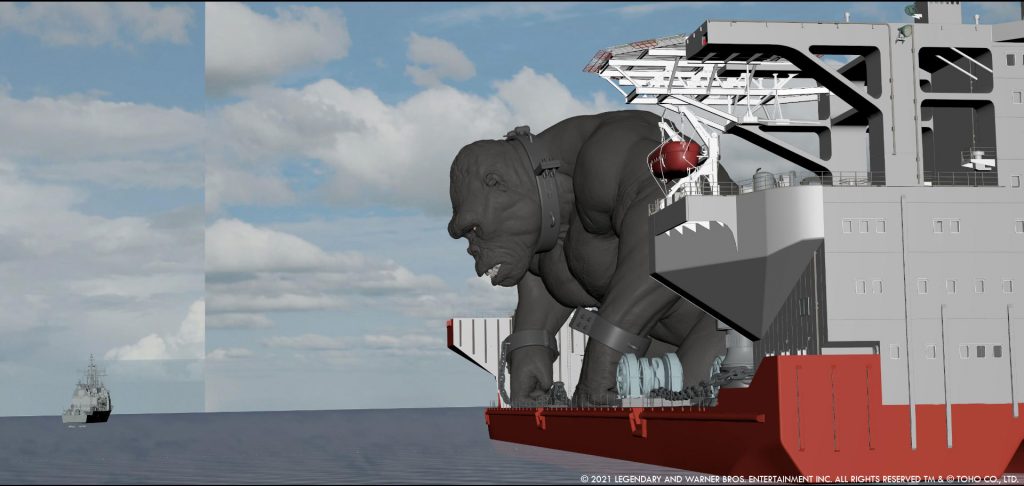

Chris Mulcaster: When creating hero assets like the ships, we always start by making 3D cameras and lining up our models against the photographic reference. This creates a platform for all reviews so we can compare against the real life ship all the way through the asset creation.

In parallel, we pick shot angles from the previs and layouts and create ‘jump cameras’ that stitch a series of hero angles in one camera, keeping the orientation of the asset at origin. This gives us the benefit of focusing on the details of the asset that we will see through the cameras in the final shots. For many of the ships, we created detailed interiors based off blue prints for the moments that Godzilla splits the ships and reveals all the areas within.

There were two unique ships we created, one was the ‘transport ship’ specifically designed to carry Kong. We customized and developed the art department model to work with the practical set piece containing a partial build of the bridge and the deck anchors that constrains Kong. For the other ship, filming took place on the USS Missouri in Hawaii. We had to partially rebuild sections of the ship from photography and adapt it to fit in to a more modern guided missile destroyer. This involved a lot of custom work to merge two different style and scale boats together.

How did you handle the FX challenges of the water and the wet fur?

Jono Freisler: Wet fur for Kong was a first for us on such a large scale. We actually needed to have rivulets of water running down clusters of wet fur, so we had to also include a representation of the fur in our Flowline sims to have the water inherit the furs movement and drip off in natural looking locations that corresponded to what Kong’s fur was doing.

For the actual water simulations themselves, we spent a fair bit of time recalibrating our Flowline setups to work with such large creatures at the surface and below. One important thing was to sell the scale, but still have a believable movement in the sim. Since you’re dealing with such large characters, the scale of the water would move very slowly, but we still wanted it to react to characters in a realistic way that didn’t hurt the scale. All of our bubble setups had to be reworked to allow for their rapid movements underwater and size. And our above water setups had to be reworked for more creative freedom in choices. On Godzilla vs. Kong we used around a petabyte of simulation data for the whole project.

Chris Mulcaster: One of the big challenges was dealing with the simulation of over 6 million hair. For the water effects, we built a tool that took the hair and created a percentage of the 6 million hair curves converting this to geometry so we could simulate the water using Flowline. We were able to increase and decrease the percentage of hair needed based on the proximity to camera so we could efficiently simulate and interact with the hair.

Can you elaborate about the creation of Hong Kong?

Chris Mulcaster: We used only 2-3 plate-based city shots from filming and due to the nature of the action, almost the entire sequence in Hong Kong is full CG. There was extensive drone and helicopter footage shot on location and with the help of Google Earth and our Models Supervisor, Matt Bullock, we were able to fully understand the geography of Hong Kong and create detailed plans for the Hong Kong city asset build.

Similar to the way we built the ships, we used shot cameras to isolate areas that needed greater detail in the city and as the sequence progressed, so did the amount of buildings. We created over 300 unique buildings and made a number of generic Hong Kong style buildings that were unique from all four sides, so we could rotate and populate the city further. We then had to populate the city and gardens with trees using Forest Pack and dress all buildings, rooftops and roads with smaller details like air conditioning units, antennas and street lights.

Our Environment Lead, Andrew Bain, then took the drone footage and stitched the photography that was shot to form a base background for the city. With some meticulous clean up and painting, we were able to create multiple 2.5D set ups that sat behind our 3D buildings to work across the entire sequence that really enhanced the realism from all angles.

Our main fight happens within the Zoological and Botanical Gardens by Victoria Peak. While we tried to contain the fight to this area, the size of the monsters meant at times this was impossible. When Mecha drags Godzilla through the gardens, we had to customize Hong Kong in order to accommodate the action and almost double the size of the city as well as destroy over 40 buildings in one shot alone.

On top of Victoria Peak Mountain sits the new ‘Apex HQ’ which was built from concept art and adapted to contain the arena where Mecha Godzilla is built and meets the Skullcrawler. This was a whole other huge environment we created that lived inside the mountain in Hong Kong and is visible throughout the final battle.

How did you prepare the buildings to be destroyed?

Jono Freisler: Luckily over the years at Scanline, we have handled a lot of large-scale destruction so migrating over a decent point to jump start our development was fairly straightforward. We then spent a bit of time recalibrating the setups so that the buildings behaved in a controllable way which also looked cool when a giant lizard was thrown up against one. All of our buildings were split into unique building materials (concrete, glass, metal, etc.) which all have different fracture and material properties when run through thinkingParticles. We also populated buildings with furniture, papers, sparks, lights that turned off when floors had been destroyed. Lots of smaller secondary details were added to sell the huge scale, and then we ran Flowline dust simulations off materials such as concrete. All of our buildings and dust simulations were simulated at real-world scale, so getting enough detail in there was challenging but paid off in the end.

With so many CG elements, how did you prevent your render farm from burning?

Chris Mulcaster: This proved to be an ongoing problem throughout the show. In the ocean battle we were always dealing with massive water sims, huge creature and fur simulations and multiple high-res ships loaded with planes, helicopters and props. In Hong Kong, the city alone was another beast just to render due to the huge amount of geometry, trees, props and scattered debris then add Mecha, Kong and Godzilla in there and it became a real challenge.

From the beginning we had to be really smart when building the assets and spent a long time creating efficient render setups and working out how to split the elements in order to effectively feed the compositors with all the passes needed.

By the end of the Hong Kong shots we had inherited so much destruction that we carried throughout the sequence, we had to split the city in to multiple scenes. Due to the complexity of a lot of the shots, we would quite often have to make in-shot optimizations and utilize our level of detail system, swapping both geometry and texture resolutions higher and lower as needed.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Bryan Hirota: We had a lot of fun with so many shots on this film it’s hard to pick out one as a favorite. If I had to single it down to one, I think it would be the shot of Kong holding Mecha’s head overhead at the camera while he roars and pounds his chest. It was a satisfying end to Mecha’s brief reign of terror and good victory for Kong.

What was the main challenge on this show and how did you overcome it?

Bryan Hirota: The main challenge was dealing with the enormous size of the creatures. Due to their size, they needed to have believable interactions with the world around them which often meant they were destroying much of what they came in contact with. Making sure the world that they existed in was destruction friendly and having the subsequent simulations be of an appropriate scale was a constant challenge.

Your name appears on the helmet of a pilot taking off just before Godzilla strikes an aircraft carrier. Is that you under the helmet or a CG version?

Bryan Hirota: It’s a CG pilot under the helmet.

Tricky question: are you more Godzilla or Kong?

Bryan Hirota: Godzilla, but Kong is a lot of fun as well.

What is your best memory on this show?

Bryan Hirota: I attended a preview screening on the lot at WB. The movie was far from complete. It had a temp score and most of the visual effects were incomplete but the audience at the screening still responded quite favorably to it. You never know how a movie is going to be received for sure, but that gave some indication that people might like the film.

How long have you worked on this show?

Bryan Hirota: From the initial tests we did late in 2018 while the show was still in pre-production until we wrapped post sometime midway through 2020, it was a little under two years.

What’s the VFX shots count?

Bryan Hirota: 390.

What is your next project?

Bryan Hirota: I am working on an exciting project that we aren’t able to share yet but stay tuned.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Scanline VFX: Official website of Scanline VFX.

HBO Max: You can watch Godzilla vs Kong on HBO Max now.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2021