In 2021, Sven Martin explained the visual effects work made by Pixomondo on Without Remorse. He then worked on Help, I Shrunk My Friends and Upload. Today he tells us about his return to Westeros for the series House of the Dragon.

What was your feeling to be back in the Game of Thrones universe?

Honestly, after the long time we’d been part of the Game of Thrones (GoT) world, I didn’t expect to come back to Westeros. From season 2 to the final season 8 we grew and tamed some gorgeous dragons, executed Dany’s death (please forgive the double meaning) and made Drogon destroy the Iron Throne. It was a full circle, so what should come next? More dragons!

We felt truly honored as we got Angus’ call, and we were all excited to get the chance to hatch some new beasts, but I was a bit scared also and not sure if the new show could follow the massive footsteps of Game of Thrones. Luckily my German reluctance was unfounded as the show is fantastic and has rightly become a huge hit.

How was the collaboration with the showrunners, the directors and VFX Supervisor Angus Bickerton?

Angus made us part of the filmmaking crew right from the beginning. Throughout the whole process, from pre-production over the shoot to the final production, he promoted the creative exchange between the art department and us and was open to ideas – always with the best result in mind!

With his background as director and storyboard artist, Miguel Sapochnik was the driving force behind the visual direction of ‘House of the Dragon’. He had a very clear vision for the look of the show and could give very specific notes. Ryan Condal is the master of the lore, he made sure that everything was correct, down to the sigils of the banners, counting the feet of the dragons.

Working in visual effects, you normally don’t get in contact with the directors very much on an episodic format, but due to our early involvement in the virtual production, we did also meet the directors and DoPs of their sequences. Greg Yaitanes showed great interest and he often came to us at the brain bar expressing his excitement about the new LED volume technology.

With so many people involved, it was to Angus’ merit to bring it all together. He is just fantastic and with all this responsibility, he was always the nicest person you could talk to.

What were their expectations and approach about the visual effects and of course the dragons?

What I appreciated is that House of the Dragon is not just a copy of its predecessor. The production team brought in new ideas and a new style without losing the connection to the beloved world GoT created, meaning, the approach was still to combine real sets and locations with digital enhancements without getting too obviously fantasy.

A new direction for example was that the camera was allowed to be a real-world camera. The physical aspects of the lenses got used as additional stylistic device – both on set and on fully digital created shots. Lensflares, dirt, degradation towards the edges – on HotD it was allowed, more than that, it was desired.

How did you organize the work with your VFX Producer?

The show’s VFX was split between PXO and MPC, with additional supporting studios. PXO’s VFX producer Sebastian Meszmann is also a veteran of GoT and was responsible for bidding, planning and executing the whole show. As always, it is a close collaboration between the producer and the supervisor, both understanding the needs of their counterparts. Sebastian managed to give me a lot of time to focus on the creative side, which was crucial to meet the high standards we set ourselves.

But it was not just the two of us, Susanne Fendt and a fantastic production team supported Sebastian while I could share duties with my co-supervisor Mark Spindler. I have high confidence and trust in Mark’s work, because we’ve done several projects together, including Game of Thrones, so there is a long history and trust already.

Have you change your approach about the dragons after Game of Thrones?

Our basic approach was still the same: grounding the dragons as much as possible in the real world and treating them as animals and not as fantasy creatures. But the big new deal was that we had to create four completely different looking dragons this time. Viserion and Rhaegal in the past have been more or less twins of Drogon, with slight changes in texture and shape only. Syrax, Arrax, Vermithor and Vhagar have not very much in common and differ in size, age, character, look and body proportions.

During asset creation and working on all dragons in parallel, we kept basic elements similar. It was the perfect timing, because our rigging lead Johannes Wolz had started to unify PXO’s rigs and drove the switch from classic rigging to a fully scripted approach. This enabled us to keep all rigs unified and helped in updating all dragons with the latest features quickly. The massive dimensions of Vhagar and her loose wrinkly skin were another challenge, as her detail was exponentially higher than on creatures we’ve ever done before. We decided to do the creature effects in Houdini this time, against keeping it all in Maya as done on GoT.

How did you used your Game of Thrones experience on this new show?

Having worked on GoT for so long, the experience of the team was without doubt a big plus for us. Both from a technical and creative standpoint, but even more having a deep knowledge of the show and previous approaches. The team were very happy to revisit Harrenhall, which PXO created as a 2D matte painting back in the days on season two of GoT and now built as full 3D asset under the lead of Andreas Wagner and Marko Leppänen. It was always important for Angus to bridge the two shows, understanding how things were done before and where to give it a new spin. We tried to support him as much as possible with what we knew from the past.

Can you elaborate about the design and the creation of the new dragons?

The art department provided lots of material for all dragons, both 2D concepts as well as 3D turntables done in zBrush. Additionally, we produced 3D printed head maquettes and refined them with hand-painted skin color. These heads were used on set as lighting reference along the usual chrome and grey balls.

We also received a small dragon bible with basic information about age, sex and character. While the modeling team started to create a clean base mesh and define the appropriate level of subdivisions with optimized edge flow, our concept team did new concepts stills based on the provided production paintings. The main idea behind this step was to use patches of animal photography instead of paint strokes. The transition from a concept painting, which leaves room for interpretation, to a detailed photo reference is quite tricky, as it’s crucial to maintain the character of the dragon. Nevertheless, I found this step important to take first, before proceeding doing the actual textures and shader.

With the approval of these new concepts, we started the high detail sculpt based on the created base mesh. Our priority was on Vhagar, being the most complicated dragon in our lineup, and Syrax, which was needed by MPC for their opening shots in episode one.

Sculpting worked backwards from the head, over the body to the wings with special attention on areas we knew might be very close to camera.

I asked the team around creature asset lead Tom Herzig for a new approach on the wing hands for the dragons. We looked at fruit bat references and also the human hand again and defined a more complex bones system within the hand. This enabled animation to bend and squash the palm better and the thumb bending forward while five fingers are aiming backwards. Against a bat we shortened the thumb and shifted it up the wrist away from fingers and palm. This helped to avoid the proportions of a human hand. Some back and forth with the rigging team testing the deformation brought us to a better wing hand shape.

The creature team really enjoyed giving each dragon their own personality. Arrax, the youngest and smallest, has not much skin detail but a very translucent skin. It was important to the showrunners, that Arrax does not get too many visible wrinkles or hard scales. Therefore, the texturing and shading team, led by Claudia Marvisi and Sean Raffel, created additional fine subdermal textures, which would be revealed in areas covered with thin skin, e.g., when the muscles are pushed outwards and stretch the surface. With no specific color and pattern on the outer skin, these subdermal layers and the SSS gave the dragon its final look.

Syrax has very long horns and large, semi-rigid scale plates on her neck. An interesting detail is the ornament engraving in one of her long horns, done by her rider Rhaenyra over the years. We made the letters grow, softer and change in color along the horn to show the transformation over the years. Old trees with love engravings were the template.

Vhagar, being the oldest dragon at this time, is defined mostly by her body posture, her hanging skin, her wrinkles as well as having eczema and barnacles living on top of her skin.

The goal was to find a good balance between looking old but still powerful. Looking at her partially emaciated body with muscles peeking through, I often described her as a female dragon version of Iggy Pop. Her saddle, with the multiple layers of ropes attached by former riders and aged and weathered over the years, contributed to her look as well. Angus wanted her to be her own ecosystem.

Vermithor was the last dragon we’ve worked on. It was planned to mostly see his head in the scene, so the initial idea was to re-use Vhagar’s body and concentrate on a new head. We started with the same base mesh, but while working on the head sculpt, we realized it’s easier to do a full new version to stay true to the production designs. Vermithor’s skin is paler and thinner after being in that cave for so long. We tested the shader also in a daylight scenario but more importantly in a warm single fire lit environment as seen in the sequence.

Can you tell us more about their rigging and animation?

As mentioned earlier, the biggest advantage was the change to universal and scripted rigs. With the experience that an animation rig is never really finished until close to the end of animation, it was important to distribute and roll-out new features and fixes to all dragons simultaneously.

We broke down the rig into sub-categories, which were used to assemble the different dragon rigs. For optimal performance, the team created different levels of detail, which the animation team could switch upon needs.

Nevertheless, most of Johannes’ time went into optimizing the rig for speed. As a result, even on higher LOD versions, animators could run the dragons in real-time. The animation team was tasked wit a lot of different animals this time, speaking of the four dragons, but also two stags, a boar, a spider and multiple digital doubles. Phillip Willer and Joakim Riedinger split duties on leading the dragon shots, as we had more than ever before. Careful planning and the creation of re-usable animation assets made the animation a smooth experience. During production, the team incorporated additional animation helpers on top of the rig to get a quicker result on overlapping animations, like when the chest up and down movement travels down over the hip to the tip of the tail.

A detailed facial rig combined FACS poses, additional dragon specific features and joint driven areas. With the dragon heads sometimes filling the whole frame or closeups on one eye only, we took special care of the face. For example, when the lid is sliding back, the eyeball is pushing outwards and retracting when the eye closes again. Subtle acting shots were not new to us, as we had done similar scenes in close framing on GoT before, like Jon’s first encounter with Drogon or their last one in the destroyed throne room over Dany’s dead body. This time Vhagar had to burn Laena and hesitated to do so. It was great to read in user comments afterwards, how well this inner conflict did transport over to the audience!

Did you receive specific indications and influences for the dragons and their animations?

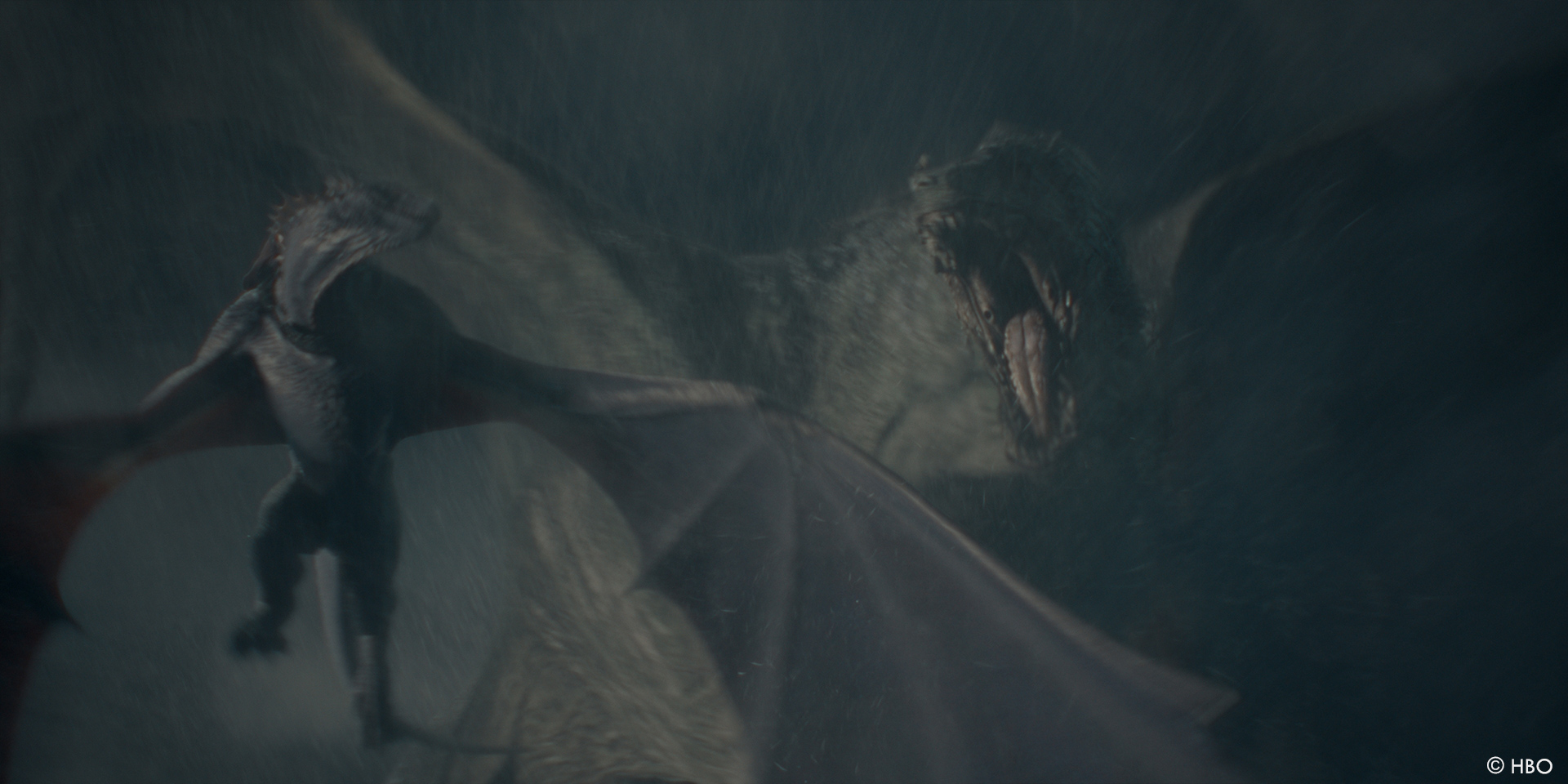

One thing was important to us – to recognize and differentiate the dragons based on their flight style. It might be most obvious during the aerial chase between Vhagar and Arrax, the oldest and largest versus the youngest and smallest dragon. Angus and the showrunners had a clear understanding of the dragons’ characters and how they are connected to their riders.

Vhagar has lost her rider and is on her own for a while now. Her age displays in her hunchback pose, which we carefully tried to never break. This was tricky sometimes, especially when she is flying up steeply and you quickly tend to bow the spine up like a ‘U’. Her head stays always lower than her shoulders, with the hump and saddle on top. When Vhagar is airborne, she is only performing the optimal and minimal movements, because she is experienced and knows where to spend her energy.

Arrax on the other hand is young, more energetic, and playful. You can see his fear and nervousness when confronted with Vhagar in the storm in the final episode. In this one shot, he looks like a moth against a condor-like Vhagar with many more irregular flap cycles against the gliding truck right above him.

The interesting thing about Vhagar’s performance is that she feels old and crooked when on land but is a powerful dragon when airborne. I had to think about that famous scene in Disney’s 1977 classic The Rescuers – that’s why we used an albatross as a reference for the shot where Vhagar runs over the dunes and heads up into the sky for the long ride with her new rider, Aemond.

Have you use procedural tool to help you such as for the wings during the flying scenes?

To save time and to reduce the exchange between departments, we divided aerial shots into ‘needs simulated wings’ and ‘animated wings’. Getting a good-looking performance out of the membranes can be quite tricky when doing FX simulations. When the dragons fly at high speed the wing flaps do not always create the bulging you’d expect; the wind direction, the gravity, sudden moves, the tension of the membranes, everything has a massive influence on their behavior. That’s why we added more secondary membrane features and controllable wind ripples to the animation rig. When on the ground and with the wings spreading and contracting, I knew we would get much better and realistic results running proper cloth simulations on the membranes.

Some of the dragons are really big, how does that affect your work?

Some of the aspects I have mentioned already. The short answer is: large in frame – more detail. It’s most difficult to deal with large scales during pre-production, when you don’t have the plates yet and nothing real to compare against. Vhagar is supposed to be 90 meters long with a wingspan of 150 meters, so we added a digital double of Aemond to our turntables to get visually reminded about the scale of the dragons.

The asset team performed pixel density checks and careful planning of the UDIM layout to provide proper resolutions in texturing and rendering. Compared to previous GoT models we had a much higher subdivided basemesh, otherwise we would not have had enough information for the skinning. Optimizing the rig performance was therefore crucial for a smooth animation process.

To get more realistic skin behavior and wrinkles, Houdini artists increased the mesh even more, while still having a reasonable performance. Not just gravity is affecting Vhagars skin alone, also wind pushing the lose skin back when flying at high speeds. New on HotD is that the dragons have saddles now. Following individual designs, these were built as full-sized versions by the production for each dragon. The saddles were used on the motion-control buck and carried the actors. Where it was easy to put a saddle on Vhagar, it was trickier to get the saddle on Arrax without limiting his performance. As shoulders do not rotate around a pivot outside the chest, the triangular shoulder setup is contracting the area between the shoulders during an up-flap massively, leaving not much space for saddle and rider.

Large dragons have a big influence on their environment also. When Vhagar is getting up from her rest in the dunes, massive amounts of sand must react. The FX team, helmed by Marc Joos, created a fully procedural dune environment, with different layers of sand, grass, roots and debris as Houdini simulation. Not yet having the proper Vhagar model at the start of production, we did early tests with a scaled-up version of Drogon landing on a dune and kicking off a sand slide while displacing the ground underneath. Different simulation techniques were combined to maintain a good performance. Additionally, to the dunes, the team also simulated sand falling out of the wrinkles of Vhagar’s neck and body. Her shaking off the sand and running through the dunes is one of my favorites in the show.

Can you elaborate about the shooting of the actors on the dragons?

Over the seasons of Game of Thrones, the techniques behind riding the dragons got more complex and high-tech. Starting with a manual, muscle controlled green buck over to an animation driven, computer-controlled flight simulator.

The new setup of House of the Dragon incorporated a servo motor driven motion-base and a motion-control wire cam inside a LED volume. Coming from a hydraulic driven eight-point base, the new configuration allowed a wider range of movement. With the dragons being quite active, less of the original buck movements needed to be solved onto the camera.

Head of 3D Christoph Schmidt and the layout team around Giuseppe Balacco took the Previs from The Third Floor and arranged the data according to the edit to a new flight path, creating a long continuous animation covering the whole scene. This process can be challenging as it doesn’t allow any cheating. The advantage is that we could create long rolling camera takes to allow the director and actors longer beats on set. When the snippets are too short, it’s hard to get into the role and to perform. It’s giving as much freedom to the team on set and not forcing them into pre-defined timings too much.

We split the four-and-a-half-minute long dragon flight into logical story sections of 30 to 45 seconds. New cameras were created making the best use of the camera chip while keeping correct perspectives for the later re-projection. These pre-animations got baked down to the saddle to control the servo buck while the new cameras were driving the motion control wire-cam accordingly. This workflow allowed the on-set crew work very natural while giving us back perfectly matching plates without making compromises on the animation.

While most of the shots were shot against bluescreen LED panels, Miguel wanted to capture tighter closeups in-camera. To achieve this, we pre-rendered a 30-second-long flight through stormy clouds with lightning flashes illuminating the scenery. Two 90-degree renders did run on the LED walls, while special effects rain, smoke and interactive light on the actors completed the illusion. Even this worked perfectly very well, finally these shots were extended with digital wings, meticulously crafted-in by the comp team behind the plate rain.

Besides combining the rider plate with a CG dragon, our 3D artists extended the real saddle with a CG version reacting to the skin movement caused by the wing flaps. The extension of the reins was also tricky from a certain point of their simulated counterparts reacting onto the dragons’ movements.

How did you handle the lighting challenges?

The Driftmark episode was especially challenging. The encounter between young Aemond and Vhagar combines three different lighting scenarios which must appear as one in the end. Due to shooting restrictions for young actors, Aemond sneaking up through the dunes was shot on location in Cornwall as day-for-night where we put in Driftmark in the far distance. We had to add Vhagar into the real dunes when Aemond first sees her. Once he gets closer, we switch to a sound stage, where the art department had recreated a small part of the dunes backed by bluescreen, which we had to extend to make it look like the real location. The closeup shots of Aemond mounting Vhagar were then filmed with the actor on a motion base in the LED volume, where a virtual 360° sky was used around him to get the correct lighting, while Vhagar and the environment below were added in postproduction. All this had to be cut back-to-back with full CG shots with a digital double of Aemond.

While the dune plates were shot outside with a sunny, partially overcast sky, the studio lighting was already set up for the night look. Angus and Miguel spend a lot of time during pre-production and running DI tests to define a distinctive night look without losing all color information. LUTs were used to preview the night look in comp and lighting. Aemonds flight on Vhagar is supposed to be lit by a full moon only and a starry sky without many clouds. Compositing leads Andreas Steinlein and Michael Schlesinger created reference shots which became the blueprint for the comp team. Already in animation, with the buck plates available, we defined moon positions for continuity while staying true to the light directions baked into the plates. The lighting team picked up that information and compositing combined plates, dragons and the full CG backgrounds in Nuke. Unfortunately, this sequence was very dark in DI at the end.

In the final episode the ‘dance of the dragons’ starts at Storms’ End high above the ocean. The team around Max Wallrabenstein created a detailed model, only dim light by small fire or windows. While the different positions of the lightning strikes gave us more freedom in positioning the key light, the wet surfaces could also be used to ‘carve out’ the dragon and their riders from the dark background. When Luke mounts his dragon Arrax in the courtyard, a complex tracking shot with over 1000 frames, we hand placed puddles on the ground to silhouette the foreground action against bright flashes reflecting in the water. For full control, the lighting team led by Kevin Friedrichs, rendered each flash as separate light select, so compositing artists could animate the beats without re-rendering.

Another interesting light scenario hit the artists when revealing Vermithor in the cave. The dragon is massive, and the cave is even more so, but the sole light source is a small torch carried by Daemon. We cheated the key light position just enough to get light on the areas the audience was supposed to see without losing the connection to the plate. Luckily the first big reveal gave us Vermithor’s own fire blast as main light source, also filling the cave with illuminated smoke to keep most of the dragon in silhouette and darkness.

Can you tell us more about the fire breathe by the dragons?

Our base is always a real fire element which then gets augmented by a CG fire simulation. Thanks to GoT we have a good collection of flame throwers and Angus also shot matching elements against black. To make the fire react on the CG environment and to follow the dragons’ animation, the FX department ran simulations in Houdini.

Which shot or sequence was the most challenging?

The final episode because of its complexity and multiple elements to be combined. Knowing this from the beginning, we started early testing and began developing a setup to connect lighting and comp with a framework of presets. Especially the FX department prepared themselves early on creating tests for stormy oceans, clouds, interactive rain, skin simulations, wet maps, and dragon fire.

But besides this sequence the deer hunt in episode three was also demanding. I have the highest respect for those who create photoreal animals, as the modern audience is hard to please in this field. Both stags had their own challenges for example. The brown one on the animation side, being tied up by three ropes and trying to break free. We analyzed videos from American calf roping and found a good reference of a stag caught with his antlers in a fence. The white stag was difficult being a very rare creature and not matching common viewing habits.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

Speaking of actual short nights, it was episode ten. The schedule was quite tight, but luckily, we were well prepared. Besides the epic chase scene in the rain and its climactic and tragic kill simulation at the end, we also had to deliver the long Dragonstone bridge sequence, the balcony scene with the three dragons leaving the castle, the funeral on Dragonmount and finally introducing Vermithor.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Overall, I’m very proud of what the PXO team achieved, with fantastic sequences like the Harrenhall opener, Aemond taming Vhagar or the final Dance of the Dragons. There are so many cool shots, and the team has done amazing work.

What is your best memory on this show?

I really enjoyed working with Angus, the collaborative relationship with the VFX production crew and the art department. A highlight has been shooting on V-stage and seeing the virtual environments on the big screens. This is where digital and practical filmmaking really come together and create the final image. Our Unreal Lead Mark Dauth was on set during the shoot of all four environments and supported the team with creative adjustments of the levels.

How long have you worked on this show?

Roughly 1.5 years, from April 2021 to September 2022.

What’s the VFX shots count?

I think over 600 shots made it on screen, distributed over all ten episodes.

What was the size of your team?

A total of about 250 artists have worked on the show, with Germany taking the bulk of the work and getting global support from our PXO teams in Toronto, Montreal, and LA.

What is your next project?

I can tell you my next project hitting the silver screen: Shazam! Fury of the Gods.

A big thanks for your time.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2023