Rob Duncan has worked for nearly 15 years at Framestore. He has participated in projects like LOST IN SPACE, THE BEACH or STALINGRAD. As a VFX supervisor, he worked on films such as BLADE II, UNDERWORLD, AUSTRALIA or WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE.

What is your background?

I did a graphic design degree at college, but fell into digital effects when it was still in its infancy in the UK. I started off working on a variety of television shows, commercials and music videos, and when the technology became available I moved into feature films.

How did Framestore get involved on this show?

We have a good relationship with Working Title and they couldn’t think of anyone better to hand the work to! This was never going to be a mega-budget production and, without trying to sound like a furniture salesman, they trusted us to deliver quality work at an acceptable price.

How was the collaboration with director Oliver Parker?

It was great – he was always very available and approachable, and took on board my suggestions where appropriate. I would extend that to the producers and also to Rowan Atkinson, who was involved throughout the process. My producer Richard Ollosson and I could have a very open and honest conversation with them about what would be possible within the budget constraints, and we would all move ahead on that basis with an agreed plan of action.

|

|

What was his approach towards visual effects?

I’m sure he would be the first to admit that VFX is not really his area of expertise, so he was happy to leave many of the creative decisions to me.

Because this was first and foremost a comedy film, it was important that the VFX supported the story, and didn’t overwhelm or distract from the comedy moments. When I spoke to him after we had finished, he pointed out that he could have easily gone down the cheesy route and not really care too much about the VFX, but decided that having good quality invisible effects would be a better choice, since it would help to reinforce the thriller aspects of the story, leaving the comedy to come from the performances. No-one wanted the laughs to come in the wrong places.

Can you tell us more about the Tibet environment? How did you create it?

I was sent solo to Argentina to obtain material that could be used for digi-matte paintings for the “Himalayas” scene. This was done with a local film crew while the main unit continued in the UK.

Over the course of one day’s shooting, we got some fantastic helicopter footage of the Andes for the establishing shot of the monastery, and when we landed we trekked off into the foothills to get some more controllable tiled plates that we would need for the ground level monastery panoramas. In post, we also had to adapt the original footage to make a winter scene, to sell the idea of the changing seasons.

The monastery courtyard you see in the film is a full-size set built at Ealing Studios which we had to top up only slightly, otherwise our task was to create the view beyond the walls.

There was another scene set in the Himalayas which we had almost finished the VFX for, but it got cut for editorial reasons.

|

|

What references and indications did you receive from the director?

Because the Ealing-for-Tibet scenes had been shot relatively early in the schedule, there was time to get a local Argentinian scout to offer up some options and send them to us. We were then able to go through and narrow them down to 2 or 3 possible locations before I set off for South America. The production then left it up to me to get the right stuff – we didn’t need anything too specific to fit the brief, as long as it could pass for the Himalayas and felt remote from civilisation, then everyone would happy.

About the London sequences, how did you create the different panoramas we can see outside the office of MI-7 boss?

The boss’s office was a real location in the City of London, meaning that some of the window views are real. Like a lot of VFX work in this film, we were merely extending, extrapolating or replicating what could be shot for real rather than creating from scratch – I prefer this approach wherever possible since the basis of the scene is real and therefore it is much harder to stray off course when adding in the digital work.

In this case, where we needed to invent the exterior view, it was created from tiled plates filmed from a different vantage point on the same building, from a window cleaner’s cradle suspended at the same height as the main unit footage. Unfortunately we were unable to shoot the plates on the same day, which meant that our lead compositor Bruce Nelson had to completely relight the material to make it match (sorry Bruce!).

The plates were then split up into different layers according to depth so we could create some parallax when the camera was translating inside the office. We built some very basic geometry of the interior so that we could be sure the various camera views had some consistency.

The reason we had to provide an exterior view at all was because we needed a false wall and window out of which the unsuspecting cat could be pushed, meaning it only had 1 metre to fall rather than 30 metres – it certainly cut down on the re-set time and the number of cats used.

|

|

What did you do on the roof chase sequence in Hong Kong?

Ultimately, very little. In pre-production this was potentially one of our most difficult sequences, since the buildings chosen to stage the action were due to be under refurbishment while we were shooting, meaning that they were going to be covered in bamboo scaffolding – although this would have been very photogenic, it would have rendered redundant the key action beats written in to the script.

|

|

At this time we were preparing to digitally reconstruct all the buildings in a two-block radius in order to remove the scaffolding. On the recce trip, I took thousands of digital stills of the buildings’ facades and other details, so we could use them as textures. However, agreement was reached with the local authorities to remove the bamboo where it would otherwise be in shot, so we were able to film the sequence unencumbered – I cite this as an example of solving a problem in pre-production rather than leaving it until post, when it would have been considerably more expensive to fix and, perhaps just as importantly, wouldn’t have contributed to the storytelling in any meaningful way.

Luckily, the bamboo which remained on the blindside of the building became a story point because it was used for the henchman’s final escape.

|

|

Can you tell us more about the helicopter sequence? Which is the balance between real stunts and CG?

When I originally read the script, it seemed to suggest that an extensive amount of CG helicopter shots would be needed to achieve the required action. However the production were nervous about committing to such a large VFX sequence (understandably since it would have eaten up the whole digital budget, and then some) and therefore found a largely practical solution by shooting most of the action on a test track closed to the public. This allowed the pilot to fly very low to the ground and close to cars driven by trained stunt people.

|

|

Although this reduced the real-to-CG balance considerably, it didn’t eliminate it entirely, so we still had to create a digital replica. Our CG supervisor John-Peter Li and our lead compositor Adrian Metzelaar did a brilliant job of matching it, using a bespoke side-by-side setup that I had shot in between main unit takes. This enabled us to make it completely indistinguishable from the real helicopter long before we knew which shots would be required for the film, and acted as a proof of concept should there be any scepticism about the believability of the digital vehicle. The shots in the film were approved by the client on version 1. Elsewhere, I was sent up in another helicopter to grab aerial plates for some of the action which takes place inside the cockpit – the actors were filmed safely on the ground against greenscreen first, so that we knew which angles and lens sizes to shoot when airborne.

|

|

How did you create the take off of the helicopter and the cutting of the trees?

The takeoff was performed by the real helicopter (this time on a private golf course which had its own helipad, so it was perfectly safe to do so). We had the digital helicopter on standby for this shot, but it was ultimately not required.

Apart from the fact that it would have been too dangerous to attempt, the stunt would have required a huge re-set time if we had tried to chop down the trees in situ. Instead, we shot a plate of the trees standing up to achieve the composition, and then they were laid flat on the ground for the pilot to determine the correct flightpath as he passed safely overhead, causing no destruction.

|

|

Some weeks later, the trees were shot upright (one at a time) against bluescreen on the Pinewood backlot, with the ‘slicing’ created by placing explosive charges on the trunks. There was some discussion in the planning stages about using an industrial tree-logging machine, but the slicing would not have been instantaneous and the device itself would have interfered with a lot of the flying debris. In order to avoid obvious repetition, we blew up 10 trees, all at different perspectives to match the original plate layout. They were shot individually so that we could get perfect synchronisation with the helicopter’s path. Even this wasn’t chaotic enough, so we shot some additional debris which would help to fill up the frame with fine leafy material.

|

|

About the final sequence, can you tell us the creation of the building on the top of the mountain and his cable car?

This started as an Art Department concept drawing, which we then adapted/developed to make it fit on to the chosen location of l’Aiguille du Midi near Chamonix, France.

In the story, le Bastion is meant to be a Swiss government fortress, inaccessible except by the single cable car which has a key role at the end of the film.

The Production Designer Jim Clay was very keen for the building to have a strong minimalist look, so of course it was impossible to find anything which fit this brief on top of a mountain. Because l’Aiguille du Midi actually has an observatory on the summit (the highest in Europe) serviced by a cable car system, it proved to be a excellent aid in terms of composing the shots – we were mostly able to cover up the real buildings with our digital creation and then erase what little was left.

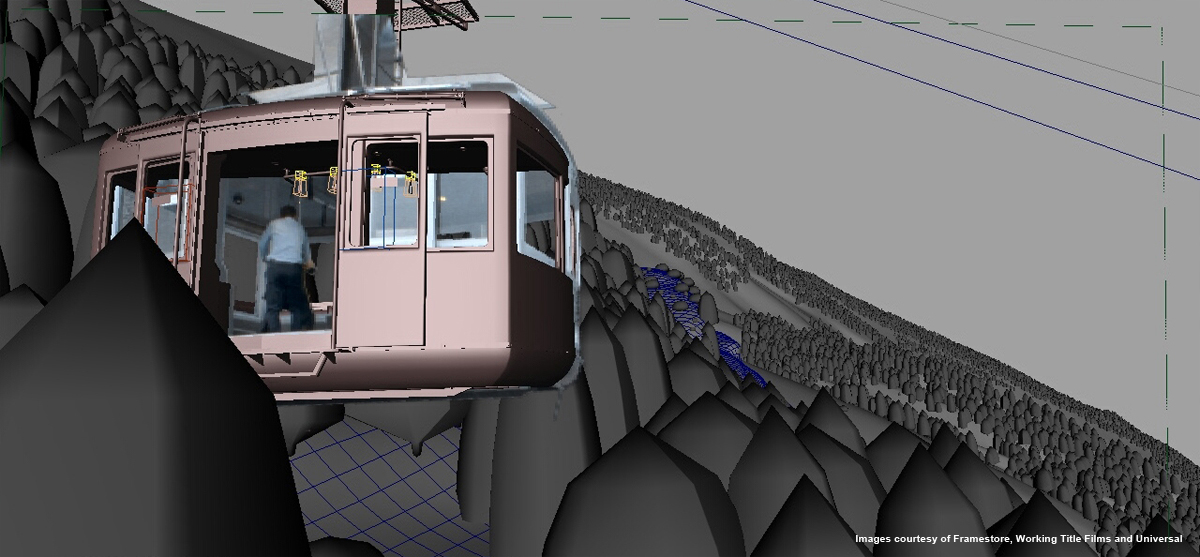

The full-size cable car (which was used to stage the fight sequence) could not be used in the big establishing shots, because of the camera moves involved, so we built a digital replica with a combination of lidar scans and photographic textures. Whenever we saw the cable car in a wide shot, we stripped out the actors from the real prop and placed them in the digital version.

|

|

Can you explain to us in detail how you create the huge environment?

The environment was always going to be a combination of real locations and invented ones, in order to facilitate the journey mapped out in the script. For instance, the summit existed so we didn’t need to create that (apart from the aforementioned le Bastion building), and when Johnny falls out of the cable car this was all shot on the slopes in Megeve, France and Surrey, England.

The major part of the digital build would be confined to the cable car journey, but that brought with it its own challenges since the total distance was quite substantial. During the sequence the camera would be looking in all directions, so we had an environment which potentially covered hundreds of square kilometers.

|

|

We knew it would be infeasible to build the whole environment, so we decided to take a modular approach whereby we built a smaller section of the mountain slope which could be bolted together in different configurations to prevent it looking like a repeat. This took care of the close- to mid-ground terrain and beyond that, where parallax was less of an issue, we were able to resort to layered-up digi-matte paintings.

|

|

Can you tell us how you get your references for this environment?

As explained before, the real l’Aiguille du Midi is a working observatory, open to the public. We discussed taking the main unit crew up there, but due to time and equipment constraints this was ruled out, so I went as a tourist along with my colleague Dominic Ridley. We spent two sessions (different times of day) capturing the environment as digital stills which could later be worked up into digi-matte paintings and also used as textures for the CG parts of the mountain.

Because we were at such a high vantage point we had spectacular and uninterrupted views of the French Alps which didn’t require much modification to work for the story.

This worked perfectly for tiled panoramas (because we were on solid ground it was completely controllable), but we still needed some moving aerial plates for the establishers of le Bastion, so it was back in the helicopter again.

I also used the opportunity to shoot travelling aerial reference for the cable car’s journey by flying up and down a generic slope on a nearby mountain range – I had mapped out in advance about 10 generic angles that I thought would be good for later reference. Although these passes would be unusable in the final film – it would have been impossible to matchmove them to work with the greenscreen fight footage – they proved invaluable for laying out the sequence and were used in the early temp screenings before any CG backgrounds were available.

How did you create the free fall shots?

In the usual fashion – stringing the actor up on wires, throwing him around, and blowing air at him to make it seem as if he is travelling very fast.

Although this would be a typical studio setup because of the rigging involved, I insisted that we shoot outside so that we got natural daylight, which is almost impossible to recreate on stage and which tends to blow the illusion straight away. Rowan was hanging from a crane arm, so rather than the rigging moving past the camera, the camera moved past the actor to get a sense of movement.

|

|

These greenscreen shots were intercut with a stuntman doing the skydive and parachute drop for real in the Alps, which was sometimes made to look higher and more consistent with our digital environment by replacing the live action backgrounds.

|

|

Can you tell us more about the big explosion of the cable car?

This shot was a real hybrid – there was the full-size cable car suspended on a crane so that we could get the villain’s performance from the right perspective; there was a third-scale practical miniature built by Mark Holt’s SFX crew rigged with explosives; and then there was the digital replica which was used up to and slightly beyond the explosion.

|

|

The miniature was blown up in the Paddock Tank area at Pinewood and was photographed at 125fps to achieve the right scale. Three miniatures had been built in case repeats were needed – we got the best action on take 2 and so used the third one for alternative angles.

Our lead compositor Mark Bakowski then added a CG missile and smoke trail (mixing in some real smoke), more explosion and debris elements from our general library, and then combined everything with a plate shot in the Alps, even making the branches react to the shockwave created by the blast.

|

|

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

The biggest challenge was definitely the cable car fight sequence, not only because of the scale of the environment that it took place in, but more specifically because of the sheer number of photorealistic CG trees needed to cover it. Our lead TD Dan Canfora took some off-the-shelf tree generating software and refined it, at the same time as developing a tool to quickly and easily populate a mountainside with low res instances for layout purposes, and then replacing them at render time with the full res versions. He had to ensure that we would be able to render thousands of trees, some very close to camera, and he came up with a number of tricks to accomplish this such as simplifying the geometry depending on distance to camera and/or splitting into layers, etc.

We were also aware that the edit was frequently changing, so we had to remain flexible in terms of background layout without foregoing a sense of continuity when the edit was finally locked – it meant that the majority of backgrounds were only rendered in the last 3 weeks of the schedule.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

I slept like a baby – I would often wake up in the middle of the night, screaming. Actually, because we were in constant contact with the cutting room, we were able to anticipate problems before they took root and could come up with a plan to deal with them. I would like to think that as the VFX industry has matured somewhat over the years, it has become easier to deal with a changing and expanding workload during a (more-or-less) normal working day. Hopefully you won’t have to ask that question for much longer!

What do you keep from this experience?

That I really don’t like helicopters.

How long have you worked on this film?

About a year in total, if you include the pre-production period.

How many shots did you do?

We ended up with about 230 shots in the film, plus a few dozen omits. Baseblack, our friends over the road, also did about 60-70 shots.

What was the size of your team?

About 50 I think.

What is your next project?

I’m not at liberty to say.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

It would be unfair to try and narrow it down to only four, since there have been so many that have contributed in different ways. Having said that, STAR WARS hit me at just the right time in my youth and really opened my eyes to what was possible – most of us in the VFX industry owe a great deal to that film.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Framestore: Dedicated page about JOHNNY ENGLISH REBORN on Framestore website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2011