In 2019, Pablo Helman explained the visual effects work made by ILM on The Irishman. He went on to work on Mank, Obi-Wan Kenobi and The Fabelmans. Today he tells us about his new collaboration with director Martin Scorsese.

// NOTE: This is a raw transcription from a video interview. Thanks for your understanding.

You have worked with Director Martin Scorsese already in the past. Can you elaborate on this new collaboration?

It was a familiar collaboration. We have a kind of a short language between us, because I work with him for the last six years. The first project we did together was Silence. And then we did The Irishman. And we work a little bit on the Bob Dylan documentary and then on Killers of the Flower Moon. It’s an incredible experience working with Marty. I mean, he’s got an incredible intuitive visual sense. He’s always about what the shot is about. It’s always about the characters. He’s focusing on the frame. But he does take the whole frame into consideration when it’s done, the story is one of those filmmakers that you stop shot in the middle of the shot, and you take a look at the frame, and you can deal with it, what the story’s about.

And he’s he’s very nuanced and very subtle, and very thoughtful. He uses all the tools of the cinematic palette that he’s got, as a director. Sometimes he uses a camera, as a witness, just witness. Sometimes the camera is part of the dialogue. Sometimes the camera is the audience. Sometimes the camera just takes us through a journey, or shows us something that the characters in the in the scene cannot see. But he wants the audience to notice that. So he’s very purposefully, moving the camera around, working with the lighting, working with the performances and the edit, this is the story.

It’s not a big VFX show. Can you elaborate on your approach and creation of the invisible work?

Well, actually, it is a visual effects show. You might not think that it is but the work is invisible. I mean, we did over 85 minutes of the movie of visual effects, but you can’t tell. And so it’s interesting that you say that he’s not a visual effects show because we are all implying that visual effects only deals with one kind of work. And maybe that is the kind that gets recognised all the time. But maybe we shouldn’t do that. Maybe we should open it up and say visual effects is this whatever that is, you know, it’s one kind of visuals but it’s also new ones and subtle and ample and completely at the service of the storytelling. And what is like for instance, without visual effects you wouldn’t have the shot like if the shot is about a car you know, going through a country road and revealing first one you know, one oil rig and then do and then three and then hundreds. If we shoot a shot you should occur on an empty field, that’s not what the shot is about. So Visual Effects has to come in, and he has to put the oil rigs. So that’s what I mean, that is storytelling.

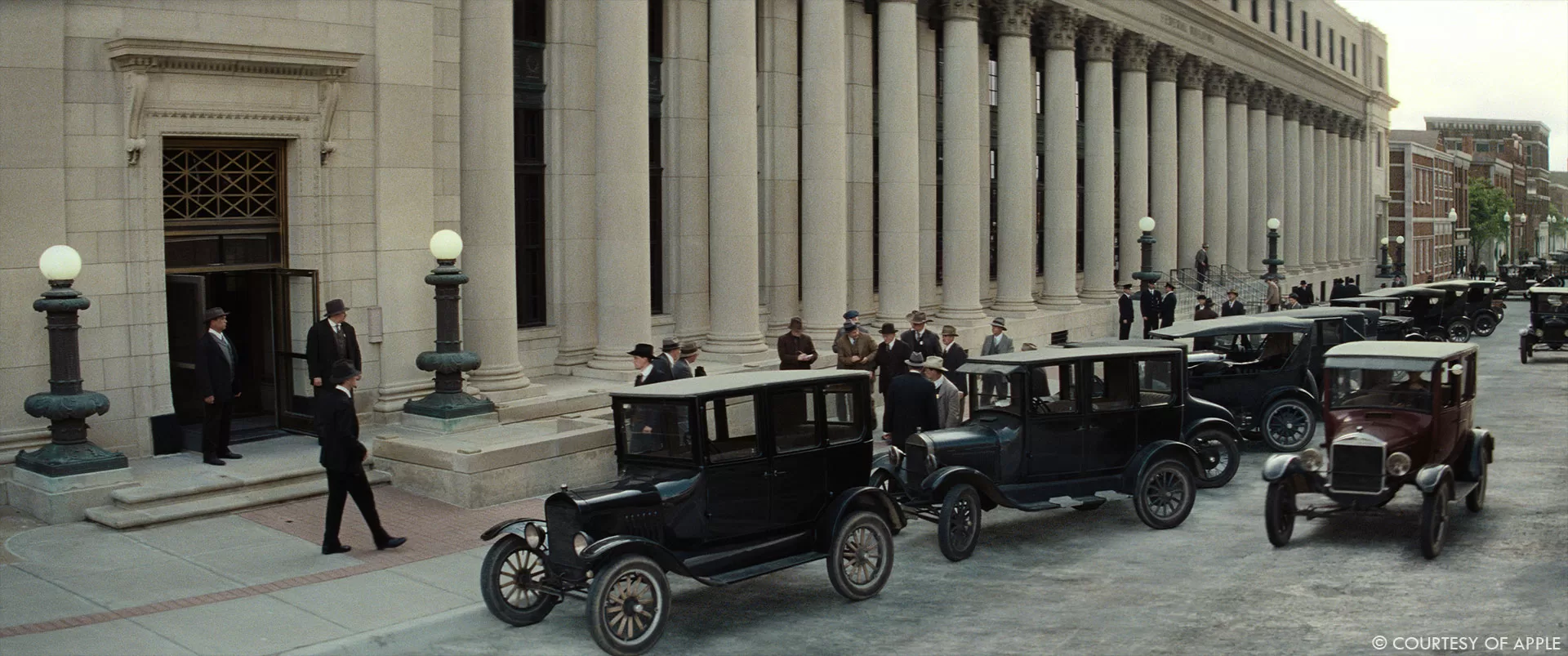

There is a specific shot, for instance, it’s a very small shot, but there’s somebody that gets killed in a car crash. But it was revealed that while we shot this, this person in the car, he wasn’t wearing a hat. And throughout the movie, before in three or four different scenes, he was wearing a hat. So nobody knew who he was, the audience couldn’t recognise who this guy is. And it was important for Marty due to extend that to the audience. So we put a CG hat on this person that was from the other scene, and we put blood there to indicate that he had been shot. And he was the person that we saw three scenes before. That is part of the storytelling incident. So that’s what I mean, together with that we did. We created the opening sequence, together with special effects. So we work it was a very special effects created the opening pool of bubbling oil, but then we corrected and changed it a little bit so that it would be more noticeable, we expand the geography of the train station, we completed the track because the track wasn’t there, we put cows there, riders, horses, crowds, we completed the town because the production design built two blocks of it, and then all the other, front and back of it. And all the other angles, we had to complete with CG cars and CG people.

We also throughout the movie, there’s the four characters that get poisoned, and they need to be sick throughout this film, but it’s a very long movie. So you need to pace that stuff up. And because we tried to do it with makeup, but because the movie was shot out of continuity, it’s very difficult to get a sense of, well, this person is getting sicker and sicker and sicker. So we did all that in, in visual effects.

There was also a section in which we restore period, documentary material from Oklahoma from Washington DC, and we had to reshoot some of the stuff because we couldn’t restore it. And so we started with a 1920 old camera, but we also we used colour film, so we have to match it to the original black and white and also the skip printing that was done. And we completed dozens of morphs for performance with the cashiers and you can really tell. And then for the movie last sequence, when there’s a radio show, we completed that with crowds. And also, in the last shot when the camera pulls up 200 feet, we completed that with hundreds of dancing Osage people.

And so when you take a look at all the work, the visual effects and the special effects we work on at four minutes of the movie, but in an invisible kind of way. And I think it’s just about time that we that we recognise that visual effects are not just one kind of visual effects is it opens you know the storytelling to a cinematic world that is that is you know, that is being if visual effects is used. Well. It’s part of the filmmaking so make sense.

Can you elaborate on a typical day on set?

Well, then this particular show was very interesting, because it was right at the beginning of the pandemic. So there was no vaccination, there was no vaccine. So it was a very odd way to work, everybody was masked, and all the departments have different colours, bands, and you were allowed to do this or not. And the lunches and dinners were very weird, because you were supposed to be this in this little cubicle, where you will be by yourself, and that goes, contrary to anything that has to do with film, because film is one of the one of the disciplines of art that is the most collaborative of all. And so, it depends on MC, to change all that. So it was a very weird kind of beginning. And then the vaccines came out. And then they all save the Osage, because we were all living in the reservation with the Osage Nation. And they were very welcoming, and they share their vaccines with so we were all vaccinated for everybody’s wellbeing. So that was was really great.

And then it was a matter of working with special effects working with the DP, Rodrigo Prieto, working with Marty, and the producers to talk about the work that was coming up and methodology…and Rodrigo and Marty were very aware of what kinds of things we need for visual effects, and what happens if we don’t get those things. And it’s not a matter of resources or anything like that. It’s a matter of what does the image, what’s the image going to look like at the end, and everything is geared towards achieving that vision, it’s not a matter of resources for Marty is a matter of getting the work to look the way he wants. And I’m always aware of that, that when we make there is no compromises basically, that when we do when we do filmmaking, it’s all about what the story is, regardless of the resources, and sometimes he would just wait until sometimes you will take a long time to get something done to rig a camera or to do some lighting, or to do a pass an extra pass of crowds, or to move the crowds in a specific way or to do elements through a second camera that is independent from the director’s camera that is catching elements for other things. And Marty is very, very patient and he doesn’t, he doesn’t mind taking the time to do to do what needs to be done. That is actually one of the most different things from any other production that I’ve been on. That there is no other priority than to get you know, the takes telling the story that Marty wants to down.

Did you use some miniature like for the oil rig or other part of the environments?

We did in max-iture. Because we knew we had to do oil rigs throughout the whole movie. And I asked for especially in the fire department at special effects department and production designed to build an oil rig, one oil rig. That was the right size, the right scale, and that it was working. It wasn’t drilling, but he was moving the right way. And he had wood colouring and the right ageing. And so it’s the kind of stuff that we would do as a miniature, but I thought about doing a miniature, but they offered me a max-iture. So I said, Sure. Let’s do it. So we did build one rig, but not in the right place for the shot, but in the middle of the field. And we did a lot of photogrammetry. We had a helicopter going around and doing photogrammetry and within textures. And all that became the basis for our CG oil rigs.

We also in that vein, we knew we had to complete the town of Fairfax, which we shot in Pawhuska, which is a very small town. That look very similar to Fairfax. So, but because it was only two blocks, and we had to complete it, we went through the town did the photogrammetry. And we took textures and we basically did the same thing that we would do with a miniature, especially nowadays. We use miniatures nowadays for not only to shoot shots, but also to shoot textures and detail of it, and then to apply that to a computer generated model and then have the flexibility to move the camera around.

And so same thing with cars. And same thing with cows, even though they don’t stay when you want to scan and they don’t stay in there. And we try using real cows, but cows are actually pretty smart. So by seven o’clock in the morning, we had like 350 cows, and because the temperature, you know, at eight o’clock in the morning was 96 degrees, then you end up with 11 cows because they all go and go into shade, and you can’t move them anymore. So they became CG cows. But we did start with that and we scan them so. So there was no miniature per se but it was the same approach of getting production design and special effects to build things and visual effects, taking a documenting and getting data in and recreating that data to populate the move through store.

Which invisible effects are you the most proud of?

I think the whole show was invisible for me. It looks like the oil rigs are maybe the most obvious thing that we would do in not for real because you probably think well, there is no way that you’re going to get a period filled with hundreds of oil rigs, but we did build one. And so that kind of invisibility it’s the most difficult and then there were lots of things that have to do with like there are some journeys inside the car while Ernest is driving Mollie around we’re all down is completely generating CG. And you can tell there’s a lot of transitions from D such as a flashback transition that goes from daytime to nighttime. Where one of the characters basically is witnessing a crime that had to be completed in CG that was really good. There’s the sickness of them that is completely invisible. How they get sicker and sicker and sicker. It’s also visual effects. So, you know, it’s a combination of all those things that is invisible, that I love working. I like working on shows that are more on that side of the spectrum than doing something that is obviously visual effects.

What was your best memories during this show?

I do enjoy being on set, although, as I’m getting older it’s more and more difficult to get up at 4.30 in the morning, and the days are gruesome when you’re doing filming, I mean, you get up at 4.30 in the morning, and you get back into your hotel, far away from home about eight or nine a night and then you have dinner and the shower, and you go to sleep and you get up again at 4.30. And you do that over and over and over. But I would have to say that the relationships that you form on set with the people that you collaborate are precious.

And also, is the fact that you keep working with the same people over and over and over. I was on a different show, at the same time that I did Killers of the Flower Moon I was doing The Fabelmans. So like from Monday to Wednesday, I was with Spielberg and from Thursday to Saturday, I was with Scorsese, and it was a great, the kind of life that that made me think, wow, this is fun, I’m learning so much. And I’m with friends, collaborators.

And there was some shots that we were, we are with some crew that we had been shooting, you know, 15 years ago together, and then all of a sudden I turn around, and it’s the same people that have been shooting, you know, some of those shots for 15 years earlier. And we’re there, you know, 15 years later with white hair and a lot older, but with the same kind of sense of humour and collaborative sense of collaboration, and all of working on projects that are really content driven, you know, that that they have a meaningful message, you know.

Can you tell us more about your next show?

I’m working on two movies at the same time. They’re called Wicked Part One and Part Two.

These movies are based on the Broadway musical. And it’s great epic stories. Having a lot of fun.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

ILM: Dedicated page about Killers of the Flower Moon on ILM website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2023