Guillaume Rocheron is back for the last interview in 2012 on The Art of VFX! After he has talked about the giants samurais created by MPC for SUCKER PUNCH, it attacks with LIFE OF PI to the creation of unbridled elements in the open ocean.

How did MPC got involved on this show?

I got involved on the film at the start of the summer 2010. We already had experience at MPC with digital water and large scale effects in general, but there was a lot of planning and R&D to put in place for the show for the shoot and the art-direction of the CG water.

How was the collaboration with director Ang Lee?

Ang is a totally story driven director and because visual effects on the film are playing a big part on being able to tell that story, he really embraced it and totally integrated us into his filmmaking process. He would direct us like he would do on-set, with some very precise ideas about the feelings and story points he wanted to get across in each shot.

What have you done on this show?

The bulk of the work was the Shipwreck and Storm of God sequences. They represent just 100 shots but cover over 12 minutes of screen time ! We also did 2 shots with CG animals for the opening credits and well as the shots of Pi on the Tsimtsum leaving India.

Can you tell us more about your work with Production VFX Supervisor Bill Westenhofer?

It was great. Being involved with Ang since the beginning, Bill worked with us on the directions to take and helped to interpret Ang’s notes that could be very important from a story telling perspective, but sometimes hard to translate into visuals. We were reviewing the work every day with Ang and Bill over Cinesync and video-conference from MPC Vancouver.

What references and indications did you received from production for the sinking and the storms?

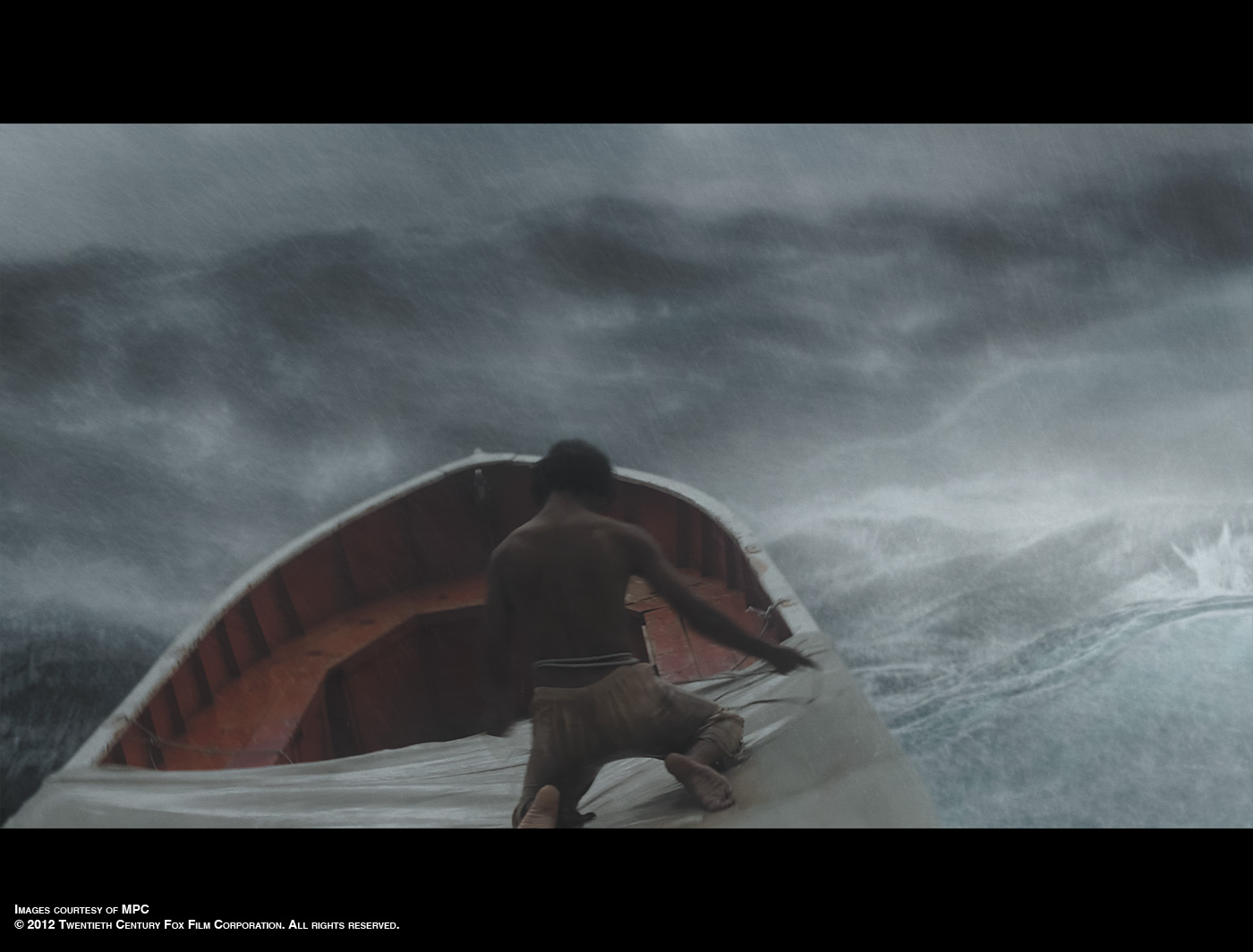

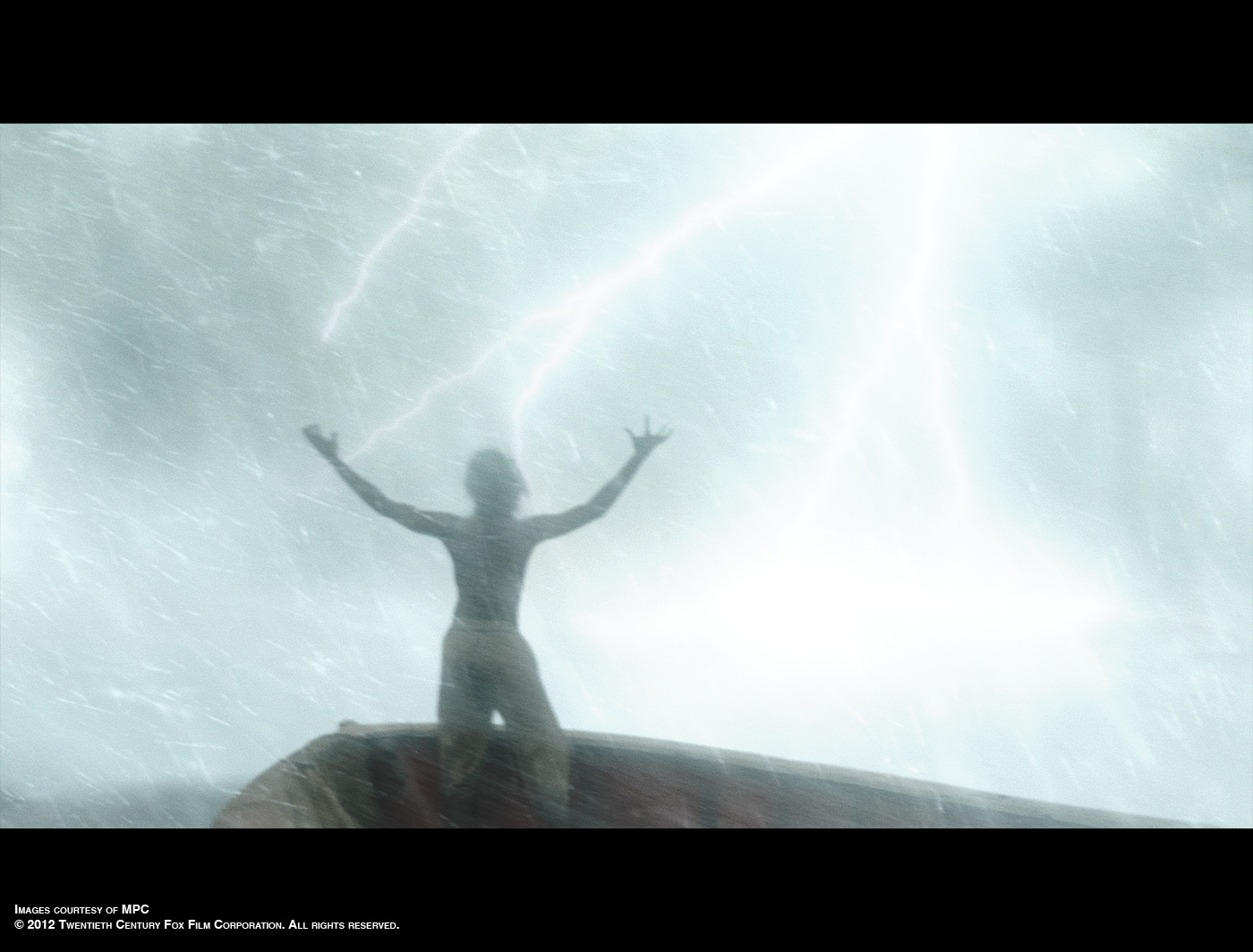

Ang was envisioning the Shipwreck being a hurricane and the Storm of God being even bigger, like a typhoon. There is not a lot of footage showing ships under those conditions but we found a few reference videos on tankers crossing the Pacific Ocean in pretty stormy conditions. We based the mechanics of the ocean on descriptions from the Beaufort Scale as well as observations from the footage. We decided to adopt as a base a force 12 scale which has 820 feet long waves, 50 feet high, a period of 12 to 14 seconds between waves and winds blowing up to 75 miles/hours.

Did you filmed any references footages?

Ang and Bill went onto a trip on the Taiwanese coast during a pretty rough day and of course shot some good footage of this. Even though the size was nowhere near the conditions in the movie, it’s it was still great reference for camera movement, views of the horizon moving up and down in the middle of those waves, lighting on the water etc…

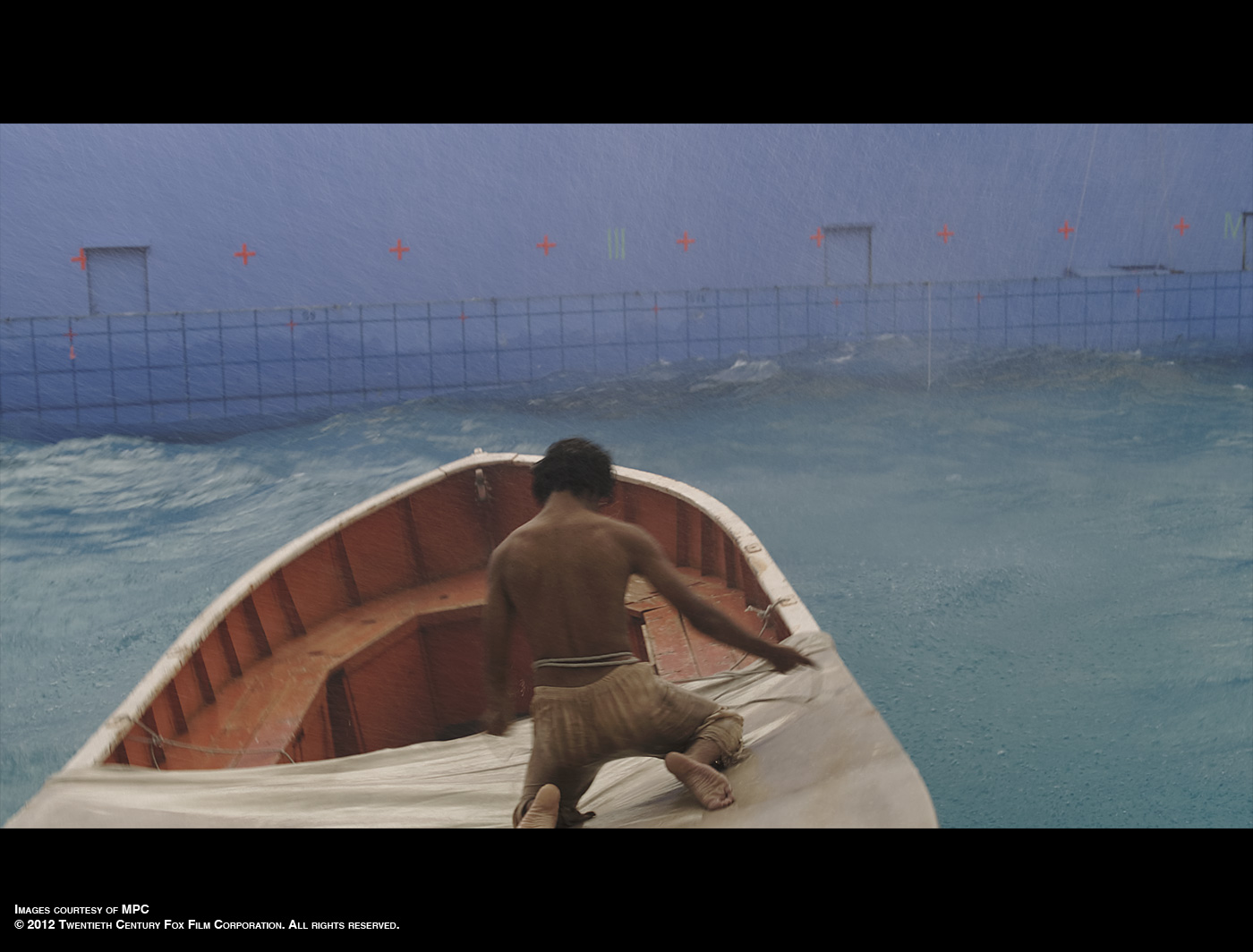

What was the real size of the Tsimtsum exterior sets?

There was 2 partial deck sets mounted on a gimbal each covering a small section of the Tsimtsum so Suraj, the actor, had a physical set to grip onto. Each set was approximately 130 by 130 feet, surrounded by bluescreens so we could extend the ship in all angles.

Have you created some previs for your sequences?

A different studio took care of most of the previs but we did take over some shots that required more precise ocean layout, animation and timing so we could program gimbals and motion control cameras.

Can you explain to us step-by-step the creation of the impressive ocean?

The first thing we realized looking at the previs and going through our pre-production was that being able to completely art-direct the waves and the ocean would be a key component in making the storm sequences work. For Ang, the ocean really was a character and it was clear that we needed to treat as such. Fluid simulations can be very counter-intuitive for a director because there is a certain aspect of randomness, that is totally acceptable most of the time, but can become a problem when simulations are the base of your shot since you are not necessarily able to lock your base and iterate on it… This is the same thing as working with water on set : the wave timing, the position and angle of the lifeboat can be slightly different on each take which forces you to adjust your camera work every take. Our shots would be worked on over a few months by a lot of people so it was key to be able to lock our wave layout and composition for us and editorial while providing Ang with a way to design and choreograph the shots, especially knowing how precisely storytelling events would have to be timed.

The second thing was the duration of the shots. Because Ang decided to use less cuts and longer takes to immerse the audience in the 3D footage, our work got a lot more complicated as the audience would really have the time and opportunity to scrutinize every detail of the characters, boats and water. We completed just over 100 shots but they represent around 12 minutes of film time; we have some shots in the shipwreck sequence that are over 1 minute long each ! That proved to be a great challenge in terms of how far we had to go in terms of details because there is a lot of time to stare at everything.

In order to solve those 2 issues, our FX and R&D team worked with Scanline on implementing a new surface simulation method inside Flowline we called “Refined Sheet” : the idea is to use animated geometry to create the ocean layout and use it as a base layer for the simulation by emitting a sheet of voxels over it to solve water flow and interactions. Our R&D team developed a base layer animation toolkit inside Maya, based on Tessendorf and Gestner Wave deformers, offering full control to our layout and animation teams to keyframe and shape any wave or component of the ocean. We would use this pre-simulation methods to layout and animate the shots, giving flexibility and quick turnaround to Ang regarding composition and timing. We would then run the simulation only when the shot was locked and approved.

The other major advantage was because we were simulating a thin sheet of voxels instead of the ocean from the bottom to the crest of the waves, we were able to concentrate our computing power to only a few feet of water depth. This allowed us to dramatically increase the amount of details we were simulating on the water surface.

Once the surface was solved, we then simulated what we called ‘the elements’: we would start by emitting spray off the crest of the waves, that would become bubbles when colliding back with the surface or mist if caught by the wind. Bubbles would then become foam when rising up to the surface. Because of the tremendous amount of wind in those hurricane like conditions, we decided to simulate a full wind field above the surface, to fill the atmosphere with mist picked up from the ocean spray and rain.

Getting the right balance of elements proved to be extremely important in order to achieve the look and to get the visual detail required by those long shots. We were literally simulating hundreds of millions of particles in each shot, broken up into many layers with different properties. Our record was on the 1st shot where Pi looks at the front of the Tsimtsum and sees a wave crashing on the bow : the spray, splashes and mist required us to simulate 1.5 billion particles in a single shot !

How did you create the interactions between the Tsimtsum and the ocean?

As for all character and boat interaction with the water, the Tsimtsum was animated against of layout ocean. The first pass of interaction would be done on the Refined Sheet. We would then simulate the usual particles for spray and foam that would lend naturally on the dynamic parts of the surface

Your sequences involved impressive waves and many elements. How did you manage this aspect on the render time?

Each shot was a lot of data to render ! The Shipwreck sequence alone represented more data that all the shows we’ve done at MPC Vancouver combined up to that date !

Between the ocean and all its layers, the characters with their hair and skin dynamics and the boats we had to devise optimized way of sending each type of information to the renderer. Our R&D lead Mark Williams did write a new adaptative meshing system for the ocean surface, using the pixel / voxel ratio to define the tessellation while maintaining the ability to add displacement maps to the surface.

We also wrote optimized render scripts for particle caches to maximize the amount of renderable water droplets. Because we adopted a full deep compositing workflow, we were able to split things down in many layers and efficiently re-assemble them in Nuke, with proper handling of transparencies etc…

How did you create the Tsimtsum?

The art department provided us with detailed blueprints of the entire ship, inspired by 1960s tankers. We also used the LIDAR scans and a very extensive photo-shoot of the practical deck sets to make sure the CG version would match details such as doors, railings, light fixtures etc…

We shot thousands of additional references in the Vancouver bay, boating around some of the tankers that were parked there to get hull details, cranes building etc…

It was a pretty extensive build, since the Tsimtsum would be seen close up from many of the deck point of views, and then down in the water from lots of different angles. Our modeling team made thousands of pieces, populating the ship with ropes, barrels and many details while the whole ship was covered with 750 4k textures.

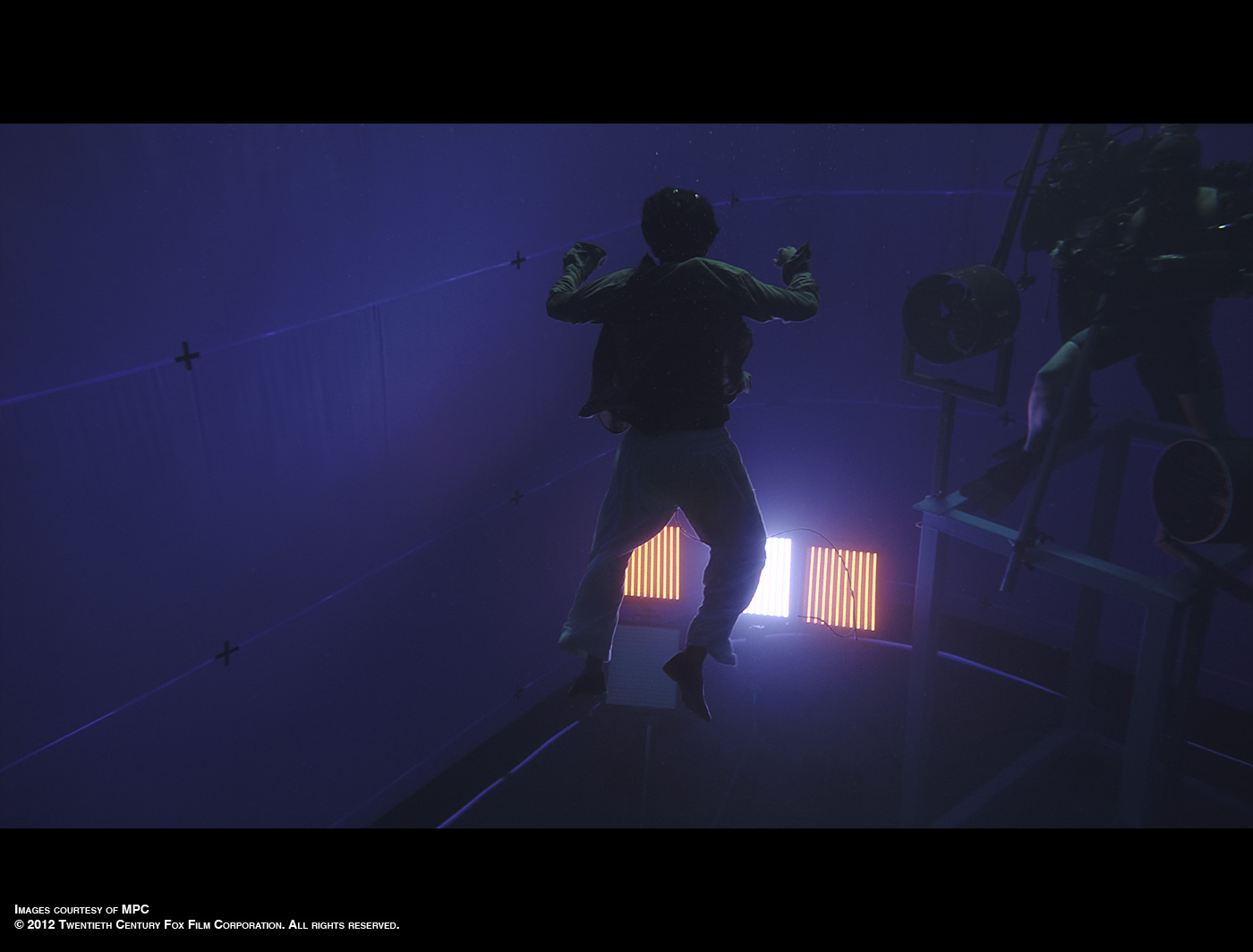

Can you tell us more about the amazing shot in which we see Pi in the water in front of the Tsimtsum sinking?

This is a 1 minute long shot that took us a couple of months to put together. Pi was shot in a special deep tank, with light sources at the bottom to emulate the lights from the ship. The water surface was created using our standard techniques for the show but instead of using the bubbles to contribute to the subsurface scattering of the water from above, we actually rendered them properly. We did an extra simulation for the big crashing and rolling wave at the start of the shot. It took a long time to carefully balance all of the elements, making sure that the Tsimtsum was visible enough but not cut out in 3D space. To help, we filled the water volume with plankton and murk to help connect in 3D Pi in the FG and the Tsimtsum in the BG.

Can you explain to us more about the lighting challenge with all those Tsimtsum lights and the lightnings on both storms?

As the show started, we rolled out an upgrade to our shading and lighting pipeline to make it fully area lights based, relying a lot more on raytracing than what we were used to do on previous projects. The Shipwreck scene is mostly illuminated by all the lights from the ship itself and we were basically shaping the ocean and the characters using those localized sources, which area lights are perfect for and using raytracing giving us very nice and accurate reflections over the surface.

The length of the shots in the movie are quite long. Does it cause you some troubles?

Yes, because as discussed previously, it is an opportunity for the audience to stare at every single details of the images. And as a viewer I think it is a fantastically immersive experience but it required much more work our end to make sure the characters and simulations were detailed enough to hold up to such scrutiny.

Can you tell us more about the asset sharing with Rhythm & Hues?

We did share a bunch of assets that we used in our respective sequences. R&H built the zebra and the lifeboat, MPC did the Pi digital double and the raft. We provided each other models, textures and look dev references. Fur, muscles and shaders were redone with our internal toolsets.

How did you manage the stereo aspect of the show?

Our stereo pipeline was pretty well implemented from previous shows we’ve done. The hardest thing stereo wise was mostly the tracking of the shots because the cameras were sometimes just looking at water and there was no way to put solid tracking markers in there.

The work was always looked at in 3D with Ang and we would do the same internally for layout and compositing as these are really the stages where we design and polish shots and 3D was essential for that matter.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

Art directing the ocean was a technical challenge we solved really well as mentioned above but I also think it was a tough thing from an artistic stand point, to make sure things still look naturalistic even though we had been forcing reality around for storytelling purposes.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

I would lie if I say it was an easy project because the complexity of the work was actually quite daunting but actually there were no particular shots or sequences that kept me awake at night.

What do you keep from this experience?

Ang Lee’s total involvement to make this film the best it could be and the opportunity to help him tell that story, no matter how complicated some of these shots were to put together.

How long have you worked on this film?

2.5 years !

How many shots have you done?

110 shots that represent a little over 12 min of screen time !

What was the size of your team?

In total 220 people got involved on the project.

What is your next project?

MAN OF STEEL.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– MPC: Dedicated page about LIFE OF PI on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2012