Back in 2018, Alex Wuttke provided insight into ILM‘s visual effects work on Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom. His journey continued with Six Minutes to Midnight and then leading him to become a part of the Mission Impossible universe.

How did you get involved on this film?

I met with Chris McQuarrie early in the lifecycle of the project, before pre-production had begun. He was starting to scout potential locations and we talked about his approach to crafting action sequences, about the ways that location informs action. We talked about the films I had worked on previously and the takeaways that could be brought to bear on the project. We started pre- production soon after.

What was your feeling to be back in this iconic universe?

Obviously very excited! I’m a huge fan of the Mission series, so the opportunity to be a part of the franchise was something I didn’t want to miss out on.

How was the collaboration with the Director Christopher McQuarrie?

Fantastic. Chris is an incredibly accomplished storyteller, and every frame within the film plays a part in telling the story. He would be very active in the blocking and framing aspects of our work, which was a fantastic education. In terms of practical shooting methodology, he was very much across the details, but ultimately happy to defer final approaches to the HODs.

What was his approach about the visual effects?

On these films, we like to shoot as much practically as possible, and this would extend to the way we approached the VFX. We would always endeavour to place a real element at the heart of the shot. This could mean SFX constructing a fully working, fully electric Fiat 500 for the Rome car chase, or sending a full size locomotive over a cliff and into a quarry to provide us with a central element for the train sequence. Having this sort of photographic truth at the centre of each shot gave us a tangible reality to base our work in.

How did you organise the work your VFX Producer?

Robin Saxen, the show’s VFX Producer, and I would first break down the film, with input from the other HODs in terms of shooting methodology. Once we had the breakdown, we could then break the work up into manageable chunks for bidding with our vendors.

How did you choose the various vendors?

We would cast our vendors based on their respective specialisms. This film had a very broad spread of different types of work, so finding the challenges that would play to their strengths was key.

Can you tell us how you split the work amongst the vendors?

ILM were our primary vendor, with work being completed between the London and Sydney studios across all the major sequences. Simone Coco headed up the Sydney studio, working on the train crash sequence, whilst the London studio, headed up by Jeff Sutherland, worked on pretty much everything else, from car chases to mask gags.

beloFX worked on the opening submarine sequence, whilst Rodeo FX and Alchemy 24 provided the pre- crash train interior work. BlueBolt produced work in the Airport and One Of Us helped out on the desert fight sequence. We also had Atomic Arts and Untold Studios on the show providing various shots across the movie. Blind LTD and Territory Studio provided our motion GFX, whilst Lola provided some complex face replacements in the airport.

Like every Mission Impossible movies, we are traveling a lot. Can you elaborates about it and your set extension work?

We travelled around the globe, with locations in Rome, Venice, Abu Dhabi and Norway. Whilst we would strive to shoot out as much of the action on location as possible, we always knew that we would need to take some set pieces back with us to our stages and backlot in Longcross. Whilst on location, we would capture as much information as possible. We captured each environment using a multitude of approaches.

On the day of the shoot, we would shoot tiles on A Camera for any shots that we felt might need a pickup, and would also sweep up after the main unit and shoot bracketed bubbles along the route of the action. For the Rome car chase, we put together an array vehicle, with an eight camera setup, giving us a 180 degree dome for use in any interior car work we might pick up on the backlot later in the shoot. This array footage also worked pretty well as a photogrammetry source if needed to patch up any holes in our traditional captures.

We also had a team from our friends at Clear Angle, who would sweep up locations once main unit had moved on, with Lidar and additional texture photography.

Which location was the most complicate to enhance?

It’s a tie between the Spanish Steps in Rome and the Train sequence.

The Spanish Steps are incredibly old and fragile, and its forbidden to even sit down on them! Therefore, sending heavy vehicles down them was not really on the agenda. Even shooting plates would be difficult; We considered drones, but that type of camera movement was just not in the language of our movie, so we had to consider other options. In the end, we decided to build our own Steps on the backlot in Longcross. These were divided into two parts, upper and lower sections, with reinforced steel sub structures. This gave us a practical base, to which we would add our digital extensions, constructed from extensive scans and detailed photography of the actual Steps.

The Train sequence was challenging in the sense that we shot it across multiple locations and times of year. We established the look of the sequence in Norway, where we shot beauty shots of the train running through the mountains. We also shot some of the rooftop fight between Ethan and Gabriel here. During this shoot, we were running an array of cameras to capture moving backgrounds to use in any interior stage based carriage work we might pick up later down the line. After a break in production, we came back to the sequence, but due to logistical constraints, couldn’t get back to Norway to shoot. Instead, we scouted UK locations and found a stretch of track in North Yorkshire that had a good topological match to the Norway terrain. Due to the differences in season, we had to augment the locations pretty heavily using data we had captured in Norway.

The Rome car chase is really cool. How did you enhance it with cars and crowd?

When we got to Rome, the city was still in semi-lockdown, so the streets were relatively empty. We would add parked cars and traffic, as well as digital crowds to get the sense of bustle back in to the city. We carefully orchestrated our cg vehicles, placing them in strategic areas to make sense of the swerving Fiat and Hummer. We paid special attention to the physics of each vehicle, rocking cars on their shocks under heavy braking and even animating brake lights. We wanted it to feel like Ethan was threading the eye of a needle with the Fiat and our CG cars.

How did you work with the SFX and stunt teams?

All of the departments on this show worked incredibly closely to achieve these shots. Since Tom insists on doing his own stunts, we had the opportunity to build some viscerally real sequences around him, taking the audience along for the ride. Wade Eastwood, our stunts supervisor, would design action with Tom and Chris McQuarrie, and between myself and Neil Corbould, our SFX Supervisor, we would figure out methodologies for achieving the action. This would come down to Neil building a series of incredible rigs, giving Tom dynamic environments to work with. We would then cleanup and extend where necessary. We had a goal of keeping our work grounded in the real, so to this end would go to great lengths to shoot practical elements. Neil and his team were key in this respect, giving us incredible elements to work with.

Can you tell us more about the impressive cliff jump sequence?

This was the very first thing we shot on the movie. The construction of the ramp alone was an incredible feat of engineering. Every part of that ramp had to be taken up the mountain by helicopter. Neil and his team designed the ramp using simulations of Tom’s trajectory, figuring out exit speeds, ramp inclines etc. We then constructed a twin ramp in the UK for Tom to rehearse on, with wires for safety. For the actual jump, we made sure we had extensive coverage of the event, shooting close coverage on a drone, a heli shooting long lens, and several ground based positions including a technocrane that had to be lifted by helicopter up the mountain. In the end, the shots were almost entirely practical barring the ramp paint out.

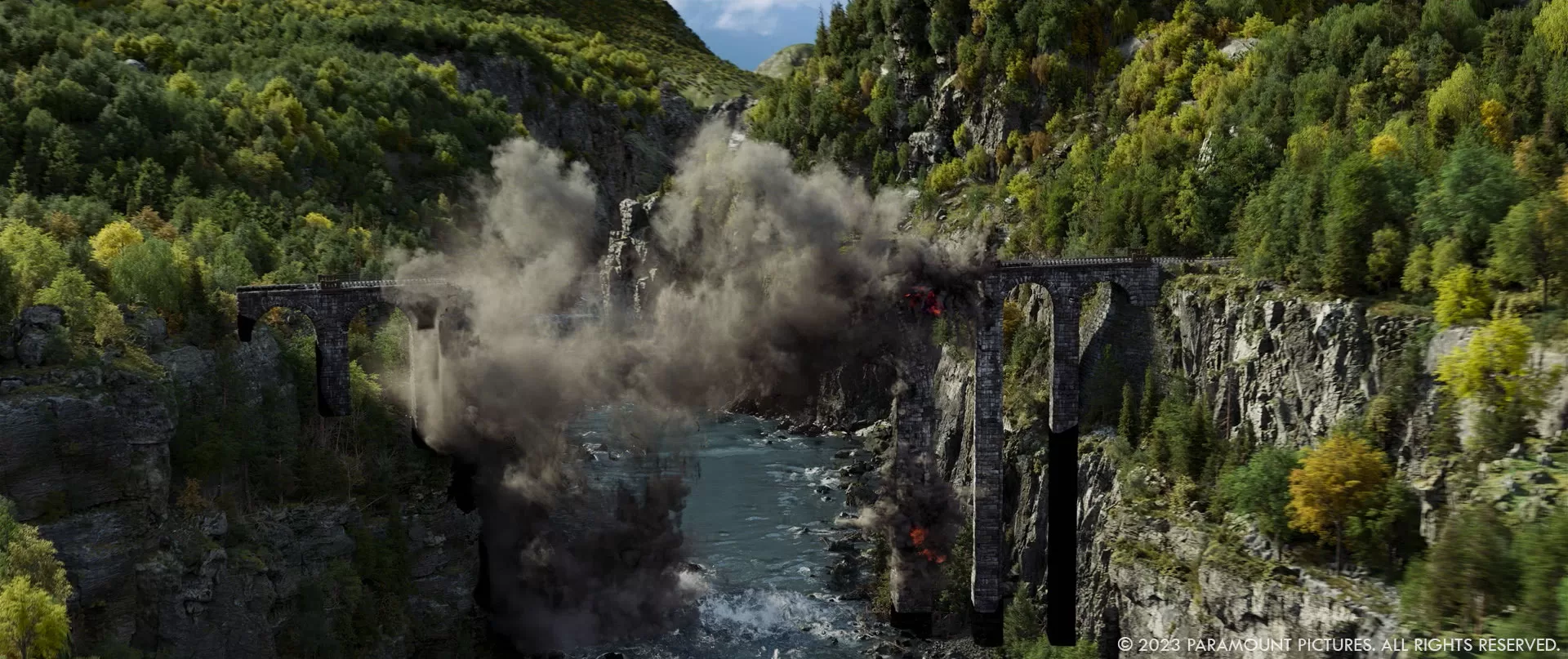

The train sequence is really intense. Can you tell us more about its shooting and especially the train crash?

We shot this sequence across a number of years and locations. We started shooting in Norway on a section of track secured by production. Art department dressed some rolling stock to look like the Orient Express and Neil and his team built a locomotive to put out front. This procession formed the basis for our beauty shots. For shots of the cast on the exterior of the train, we removed some of the art dept cars and switched in a low loader equipped with a camera crane and the vfx camera array, capturing backgrounds for our interior stage based carriage work. At the same time, we had a pursuit vehicle chasing the train in contact with us over radio, picking up HDRIs along the way. We also captured extensive scans and panos for use later. We ended up shooting train pickups on a stretch of track in North Yorkshire, since the terrain was a reasonable match for our established Norway look. Due to time of year issues, we ended up doing fairly extensive digital augmentation to pull the looks in line.

For the loco going over the cliff edge, in line with our desire to put reality in the heart of each image, we sent a full size SFX loco over some track into a quarry, shot from various fixed positions and a heli. We also had fixed positions on the loco itself, with cameras in crash boxes fitted with explosive bolts, which would be jettisoned from the loco prior to impact. The surrounding environment was a CG build, based on an amalgamation of features captured in Norway during our time there.

The slow motion train wreck, with Ethan and Grace navigating a series of jack knifing carriages, was shot on the backlot at LongCross on a variety of gimbals. The main gimbal held various full size carriages, capable of more than 30 degrees of tilt. This allowed us to put our actors in positions of real jeopardy, allowing them to navigate tumbling furniture and obstacles for real.

The final piano bar set was mounted on a gimbal capable of going level to vertical. For the dangling piano, we shot various elements of an actual piano suspended on a release rig, and shot elements of furniture crashing through the back of the carriage for real. The idea was to capture as much of the chaos of these real events as possible and lean in to the imperfections that would occur naturally in the process. The same was true of Tom and Haley’s performances. Most of the time, the tension you see in their faces is the real deal!

What was the main challenges with the train sequence?

It was an incredibly complex sequence with lots of moving parts and required absolute cohesion between all departments. We worked incredibly closely to have it all work out, and it required a huge amount of planning.

Can you explain the effects for the different face masks?

Due to the language we’d established for the film in terms of how we would move the camera, and due to the fluid way we worked, we didn’t want to be bogged down with motion control and the restrictions that process imposes. Thankfully our A Camera operator, Chunky Richmond, happens to be a human motion control rig, so could quite faithfully replicate moves on his steadicam. We would shoot a series of passes; The A side actor, then the B side actor followed by a pass of the A side actor pulling off a prosthetic rubber mask. We would stabilise and align the takes in the comp, occasionally re-projecting to correct variations in the lineups, then use the leading edge of the prosthetic mask as our wipe between the elements.

The movie is full of motion graphics. Can you elaborates about their design and animations?

We had two teams running out our motion graphics for this movie. Territory handled the Entity and Venice satellite imagery, whilst Blind handled almost everything else. For Eddie Hamilton (the editor) and McQuarrie, graphics do a lot of heavy lifting in terms of story telling, so it was critical that the graphics could convey a lot of information in a very short timespan. Clean and uncluttered design therefore is crucial. For the Entity, we looked at a lot of visualisations of Big Data, and ended up with this concept of an all seeing eye constructed of data, that appears to be looking around the room. This was important in lending the villain of the piece a sense of character and presence in the movie.

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

The opening submarine sequence provided challenges in the sense that it was the one sequence we couldn’t capture anything in camera to hinge the work off of, for obvious reasons! There’s also very little reference, in terms of what we could realistically ask an audience to believe in outside of certain hallmark movies such as The Hunt For Red October and Crimson Tide, so we made the decision to lean into these movies as a visual touchstone. In the spirit of approaching things in an authentic way, we explored shooting in the same style as these films, ie: flooding a sound stage with mineral smoke and pulling big miniatures through the volume. Due to logistical constraints and knowing what our miniature would need to do, we moved to a digital approach, but tried to hold on to the same aesthetic. This extended to the ways we approached the execution, with Joel Green and his team at Belo coming on board to execute the work. We filled our digital world with a 3D density field, and pulled our sub through this, giving us a nice falloff and diffusion, mimicking the look of these early movies. The physics of the sub explosion also took cues from Crimson Tide. It was a challenging sequence to get right creatively, but we’re all very happy with the results!

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

We’ve been working at pace on this franchise for so long now that the panic has become normalised! It’s not called Mission Impossible for no reason.

What is your favourite shot or sequence?

So many amazing moments, its impossible to choose.

What is your best memory on this show?

Again, so many great memories. Sunsets in the desert, dawn commutes along the Grand Canal in Venice after night shoots, hurtling through the Norwegian mountains on a low loader carriage, but the biggest thrill was finally seeing the completed film on the opening night in Rome and seeing everyone’s hard work on the big screen.

How long have you worked on this show?

I started in 2019, and we finished our last shot exactly 4 years later.

What’s the VFX shots count?

In total, around 3700.

What is your next project?

We’re well under way with the next installment!

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

ILM: Dedicated page about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One on ILM website.

Atomic Arts: Dedicated page about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One on Atomic Arts website.

beloFX: Dedicated page about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One on beloFX website.

BlueBolt: Dedicated page about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One on BlueBolt website.

One of Us: Dedicated page about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One on One of Us website.

Rodeo FX: Dedicated page about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One on Rodeo FX website.

Territory Studio: Dedicated page about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One on Territory Studio website.

Untold Studios: Dedicated page about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One on Untold Studios website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2024