In 2019, Guillaume Rocheron had explained the work of visual effects on Godzilla: King of the Monsters. He then worked on Ad Astra and 1917.

How did you get involved in this show?

I started, along with MPC‘s Art Director Leandre Lagrange, quite early in the process, a few months before pre-production started. Jordan was in the process of writing his script and wanted to explore ideas for the alien entity and figure out how its design and behavior could help stage the multiple encounters in the film.

How was your collaboration with Director Jordan Peele?

Jordan always has a specific idea that he wants the audience to respond to a scene or a shot, but he creates a collaborative environment between all the heads of the department to help him shape those ideas and expand on them. He involved Nicholas Monsour, his editor, and Johnnie Burn, his sound designer, very early in the process. We would always look at each other’s work and see how we could refine what we were doing to accomplish Jordan’s vision. Sometimes, the sound design would guide some visual designs and vice-versa. We did many experiments to find the perspective that would make the VFX more grounded and real within the context of his story.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

Jordan wanted the audience to experience each scene in a way that felt visceral and unexpected. We live in a time when audiences are difficult to impress or scare because they are used to seeing visual effects and CGI in almost everything. So, we focused on how to best present each moment in the film unexpectedly and embraced the idea that sometimes, suggesting things were more impactful because it required the audience to use their imagination to complete the picture. In the end, it helped us convey more compelling moments of fear or awe.

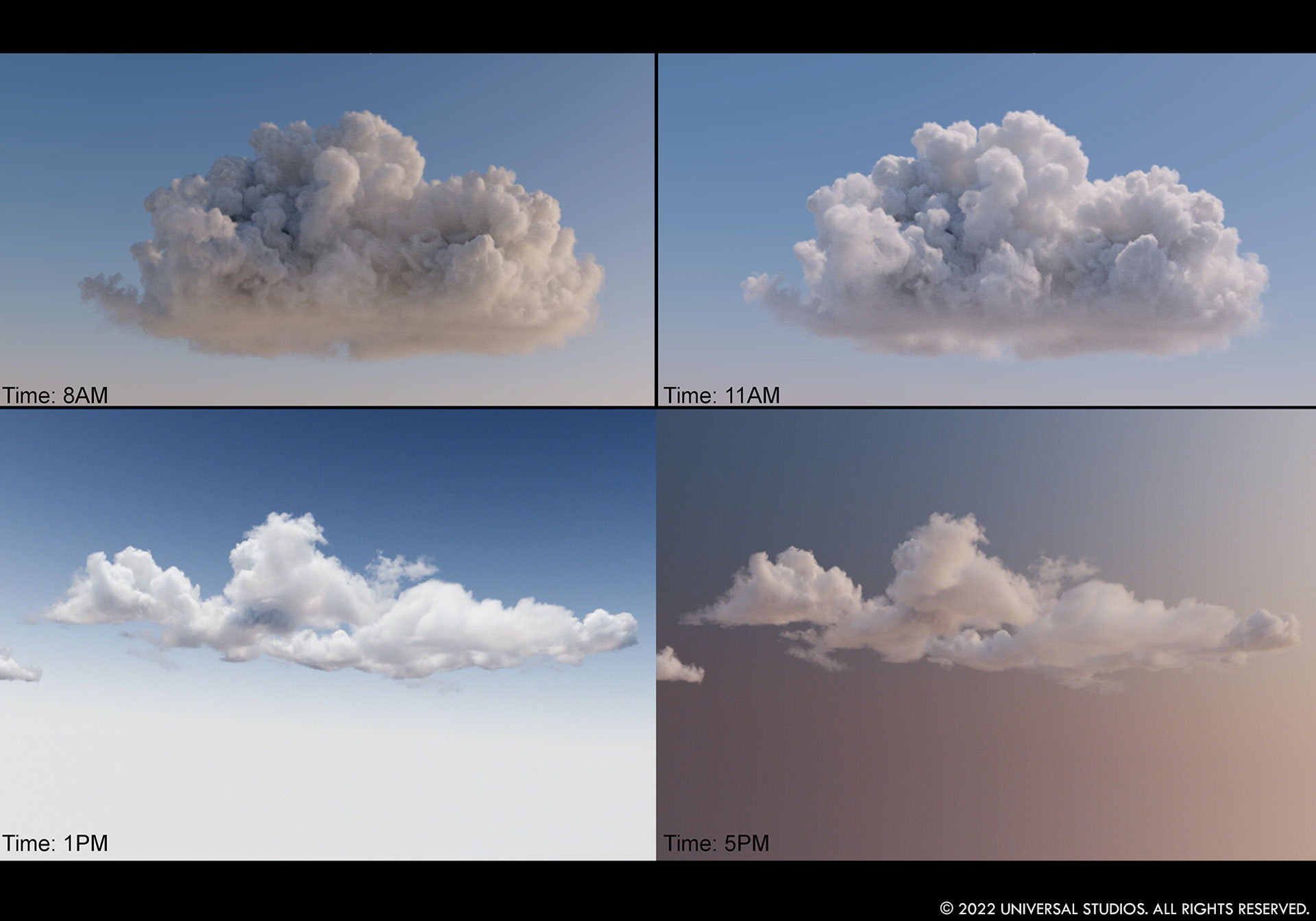

For example. as we were developing shot ideas for Jean Jacket, our alien entity, we quickly realized it was much more impactful to see glimpses of it through the clouds and suggest its shadow or presence without giving it away too clearly too quickly. And I think that’s when, with Jordan, we realized that creating and controlling the cloudy skies would end up being our greatest VFX challenge. We wanted the audience to constantly look at the sky and be scared by what they might see in it. To do so, we created CG skies for the entire film, except for a handful of shots. They had to be invisible to the audience because it would otherwise have given away that something was about to happen if they realized they were watching an effect.

Can you tell us how you split the work amongst the vendors?

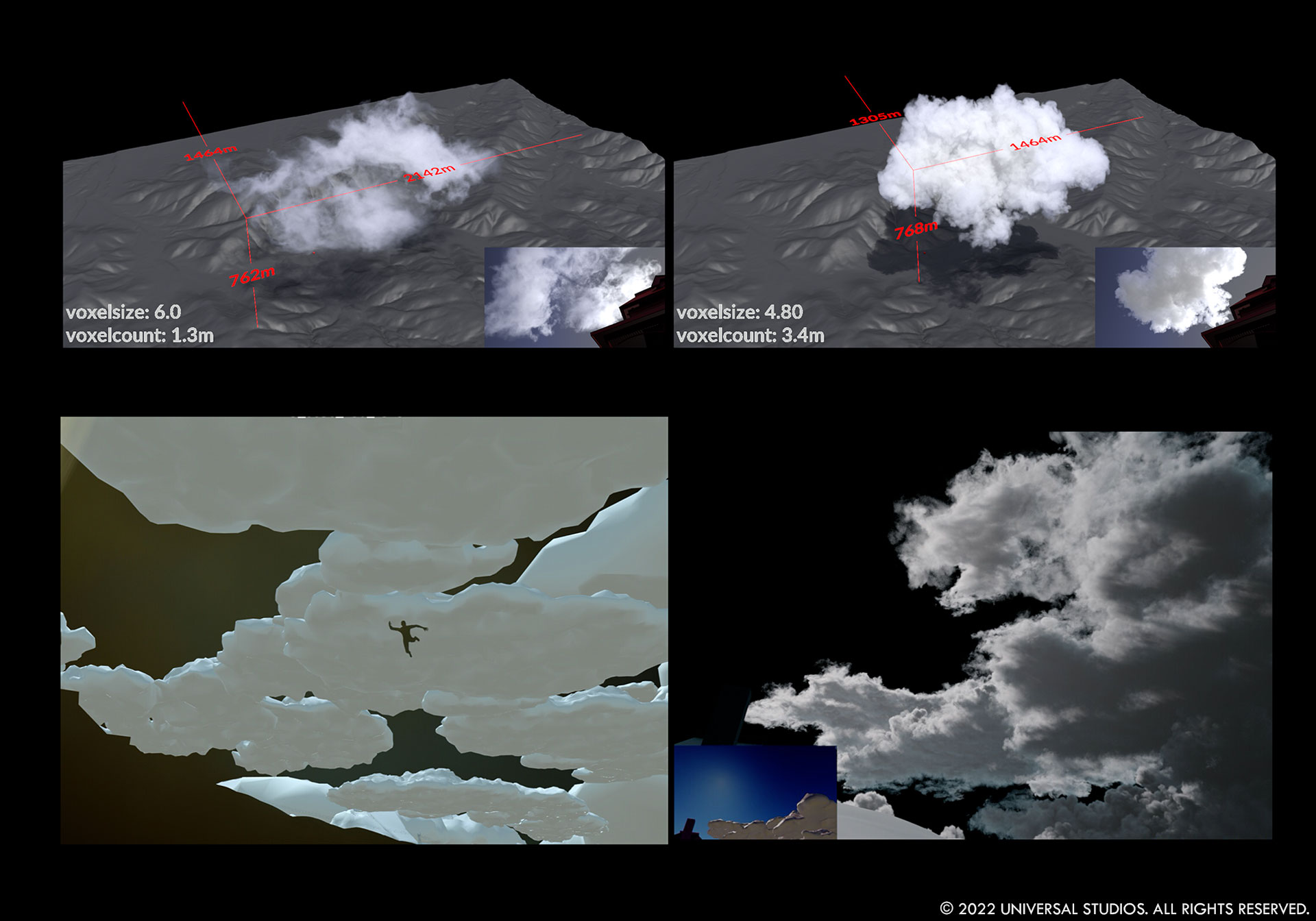

MPC, led by VFX Supervisor Jeremy Robert and DFX Supervisor Sreejith Venugopalan, executed most of the work on the movie, especially since the skies required some extensive R&D so they could be generated, and art directed throughout the whole film. We started R&D on the cloud system in early pre-production so MPC’s previs team, led by Josh Lange, could work on the shot and sequence designs using the cloud toolset than would then be passed to the team in post-production.

Universal Studio Post, led by Don Lee, provided excellent support with miscellaneous 2D comps throughout the film, while SSVFX (led by Ed Bruce) and Future Associate (led by Lindsay Adams) took on additional specific 2D tasks.

How was the collaboration with their VFX Supervisors?

As always, a film like this required close collaboration to ensure we were always aligned on what was required to serve the story best as the edit was evolving.

Can you tell us more about the creation of the skies in the film?

We were tasked with creating all the cloudy skies seen in the film, except for 2 or 3 shots where we kept the real clouds. In general, sky replacements are quite a trivial task since they are generally done for aesthetic or continuity reasons, using photographs or plate elements. In our case, we needed the skies to be completely art-directable and integrated into the ever-changing light of practical photography. So, we decided to treat the cloudscapes as modular complete CG sets, like we would assemble a CG jungle or forest, except that they had to be made entirely out of 3D volumetrics.

We started with a set of geometric approximations of clouds based on noise patterns in Houdini that allowed our previs and animation team to design the overall mass of the cloudscapes, animate them and ultimately stage how we wanted to suggest the presence of the entity in each shot. On a sequence level, we animated the drifting of the clouds. The next step was to convert those geometric clouds into volumes, so MPC devised techniques to use the geometric mass of each cloud as input and simulate different clouds based on their size and altitude to produce a realistic rendition of the animated cloudscapes. Because of the resolution of the IMAX footage, we spent quite a lot of time designing efficient ways to add details to those clouds; MPC created a tool to scatter patches of volumetric details within the main cloud volumes as a second pass. And lastly, rendering all these volumes proved challenging, primarily because we photographed the film in natural light, and each shot had slightly different lighting qualities and sun angles.

Our goal was to make sure the skies felt real and somehow unremarkable, like they were shot on that given day, instead of trying to make them too preppy or unique. It was vital for us that the audience would never question them.

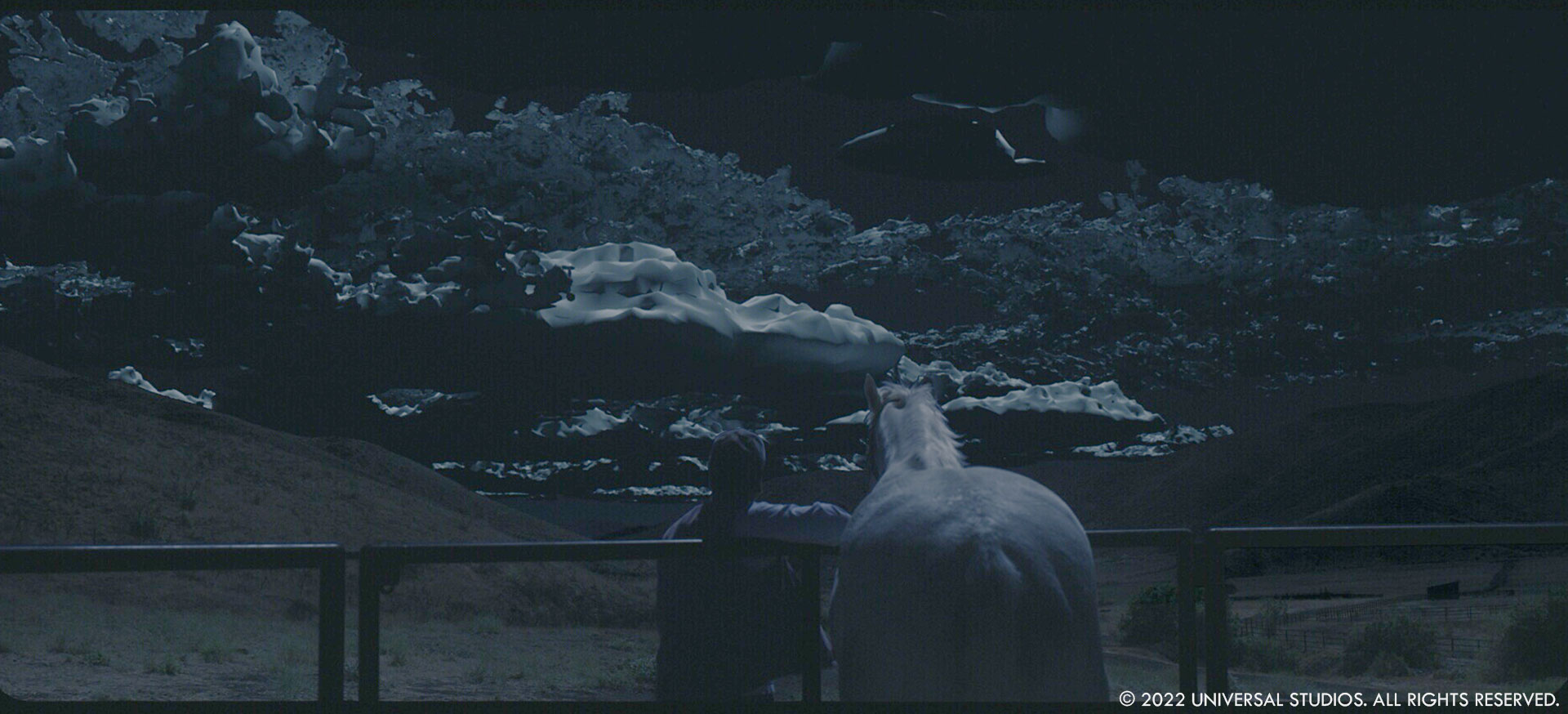

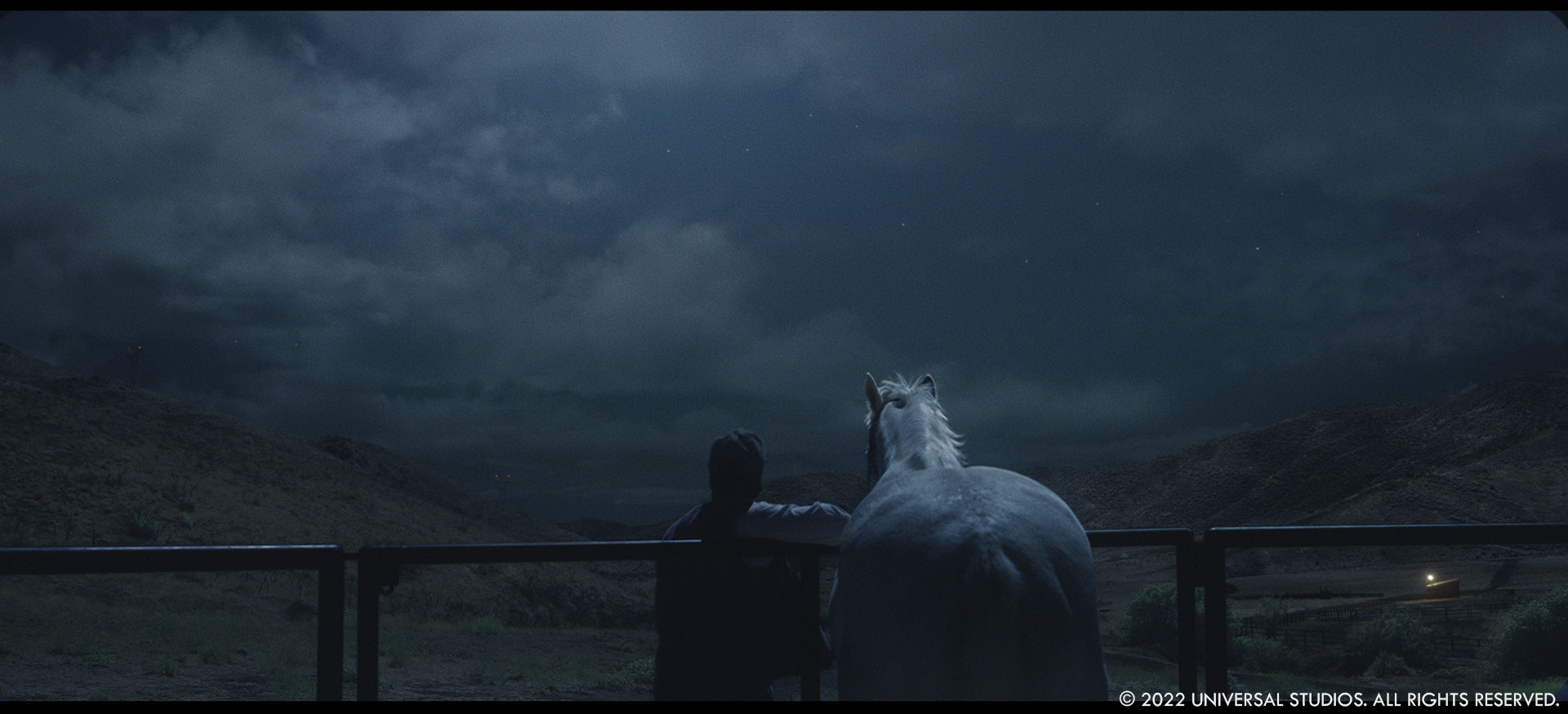

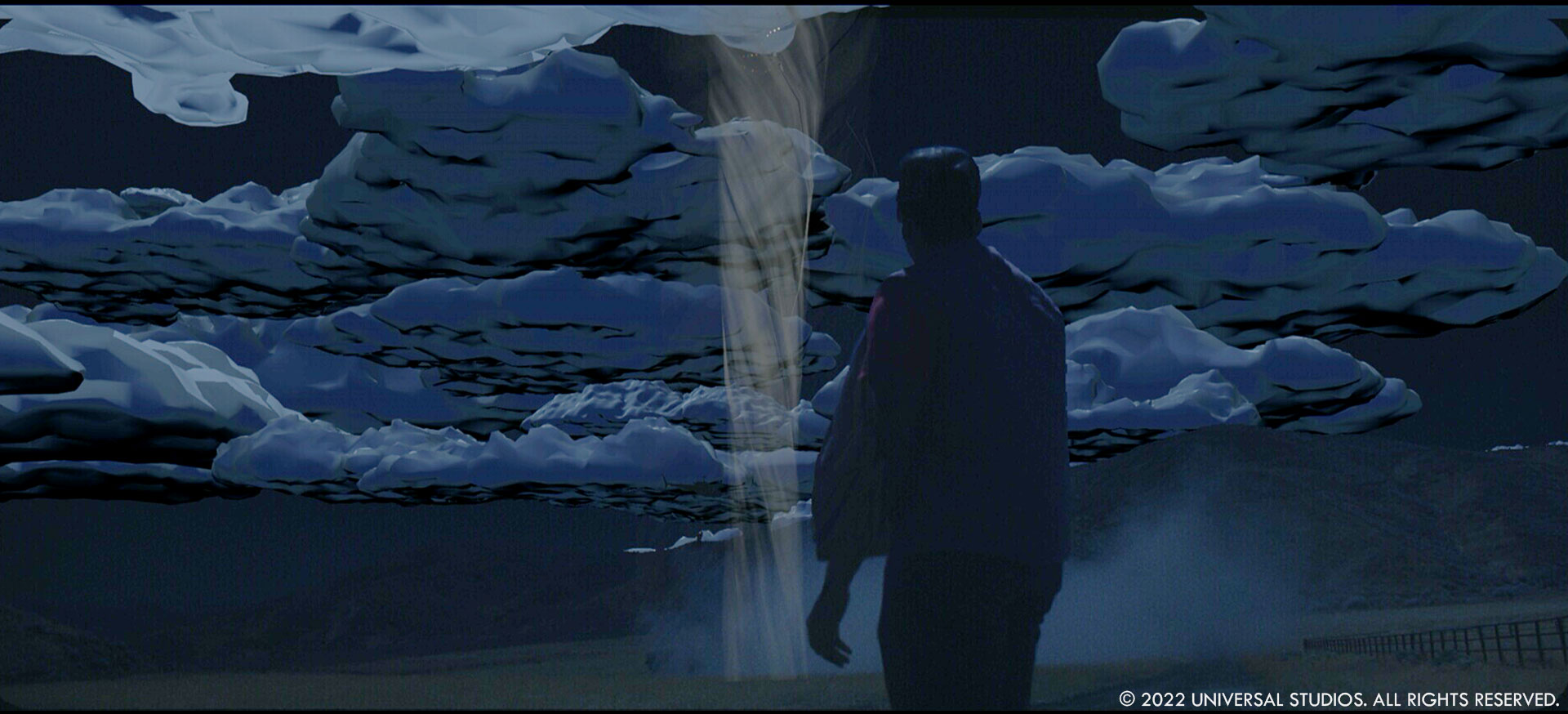

The encounters at night have a unique look to them. Can you elaborate on how they were created?

It was a close collaboration with DP Hoyte Van Hoytema. In pre-production, we went on a scout of the location a night and turned off all our lights; slowly, we realized our eyes adjusted to the darkness to the point where we could see in the distance with shapes and colors. So, we quickly discussed how we could recreate this immersive feeling on film, nights as the human eye sees, and not like traditional lit movie nights. If you put a camera on a night, it sees nothing unless you start to add lights, smoke to create a silhouette, etc. The traditional day-for-night techniques allow you to go around this problem but are very limited since you are just manipulating the colors and brightness of a bright image to give the impression of a night. We wanted our nights to feel real and immersive as we experienced them on that scout. Hoyte had experimented with infrared cameras to create the black skies of the Moon scene in Ad Astra, and we discussed how this technique could be the starting point to develop full night scenes. After a few promising tests with MPC, Hoyte designed a camera rig allowing us to film each night shot with two cameras aligned and synchronized with each other: an infrared Alexa 65 and a 65mm film camera. Shooting in the middle of the day, infrared gave us black skies and contrasts akin to how you see at night. But the infrared is black and white, so we created VFX techniques to colorize the infrared footage using the synchronized 65mm film camera. It’s like coloring a black and white movie, except we had truthful color information we could extract and apply to various parts of the image. We then ran each shot through camera tracking so we could extract a depth pass and use it to modulate the landscape’s visibility, colors, silhouette, and actors based on the distance from the camera.

Can you elaborate on the design and the creation of the Jean Jacket?

We first looked at nature, from flowers to strange sea creatures and birds, during the initial design phase. But as we went deeper into the design conversation, we wanted to develop something alien-looking, minimalistic, yet functional with its own design language. As the entity was supposed to unfold, we started to look at patterns made in origami. Jordan and I also loved the Angels’ designs in Neon Genesis Evangelion; they were very minimalistic and with a design that entirely served its function.

Leandre Lagrange and his team at MPC came up with some exciting proposals that hit the mark early on. Our next step was to consult with scientists from various fields to understand how to make our entity plausible and refine its design based on its primary functions: hunt and harness the wind to move. Professor Dabiri at Caltech, who has a lab where he studies jellyfish, was instrumental in helping us to refine our design in motion. Jellyfishes are the most energy-efficient animals in the ocean, and this is something we tried to translate into a wind-based animal; what does it need to move? How would it do it with minimal effort? How would its features have evolved to make it a deadly hunter?

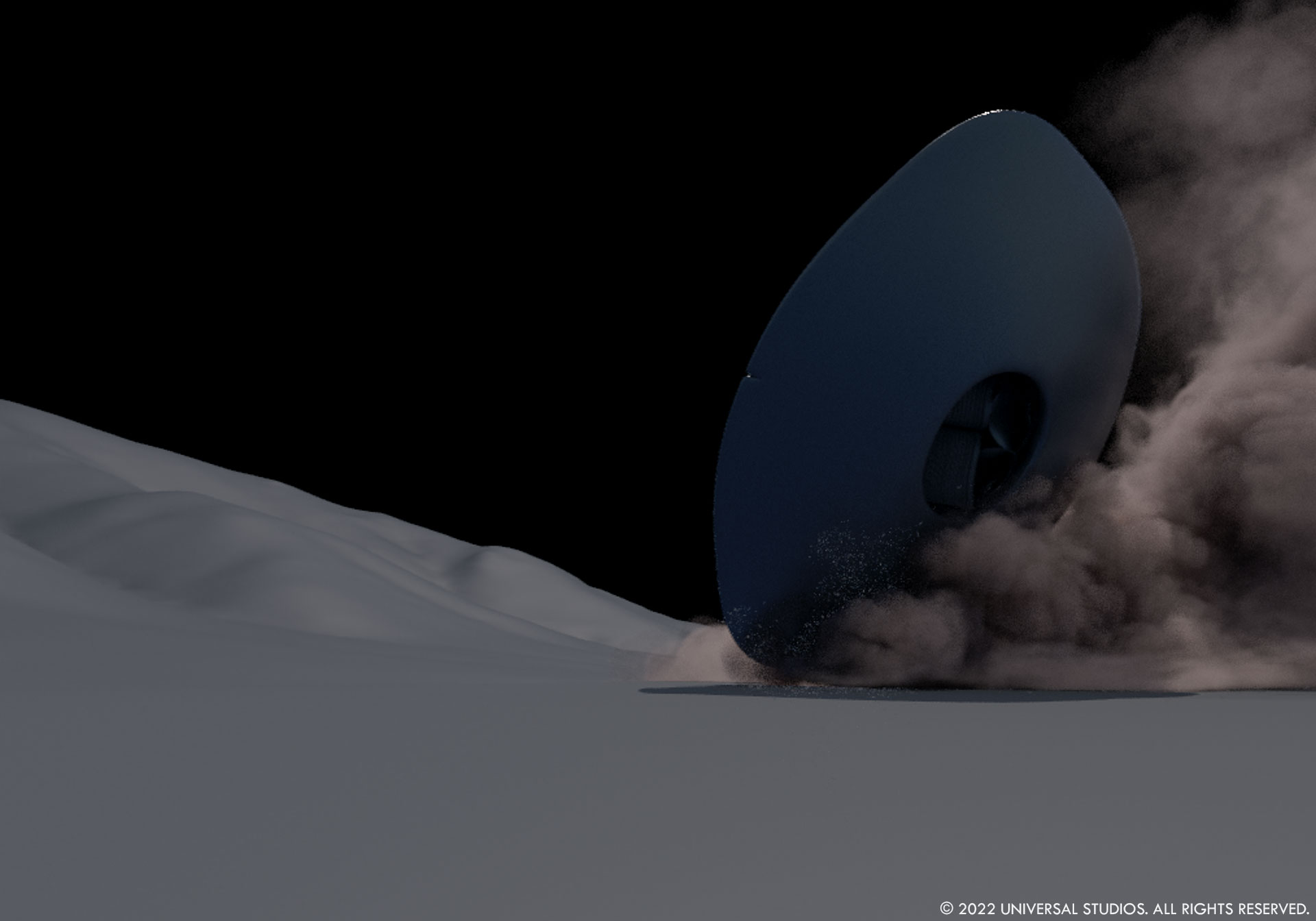

Animating and rendering Jean Jacket in shots was a challenge because of how minimalistic we wanted it to be. As a saucer, we always looked for a way to show it was riding wind currents but could also be fast and nimble. It was a difficult balance to keep it looking natural, and I think a lot of the perceived realism, in the end, comes from how it interacts with the clouds, generates dust, etc. Once Jean Jacket unfolds, we used massive cloth simulations to deform its surface and create a sense of scale and details. Again, we wanted to go with minimal textures and features, so simulating the entire character with cloth simulations instead of a traditional rigging with muscle solution became our way to make it move in the wind and somehow gave it photorealistic details.

There are a lot of interactive elements between the UFO in the sky and the characters on the ground. Can you talk about how you created those?

Most of the events in the film take place in the sky, where it is pretty difficult to understand scale, speed, and distances. So as often as we could, we looked for a way to connect the events in the sky to the ground, where the viewer has a much-cleared understanding of distance and physics.

For each shot involving Jean Jacket, we tried to capture a ground element on camera, whether dust with fans or our helicopter, debris or blood falling, or a moving wall of rain. We kept our SFX team busy to ensure we always had something real to build upon in post-production.

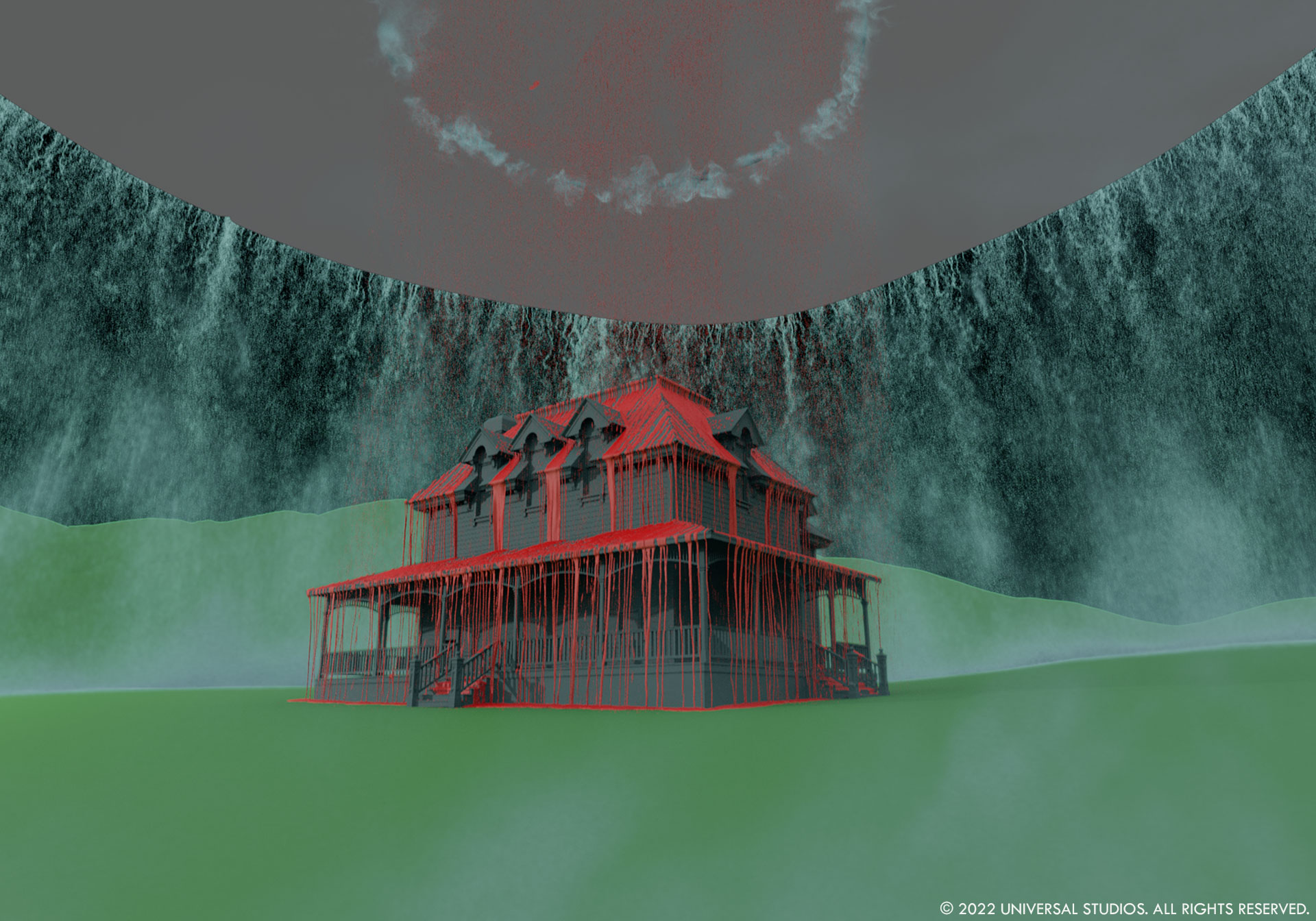

For MPC, dust events quickly became a big FX task. They had to be much larger than what could be captured on camera, even a helicopter, but we really wanted to anchor all the simulations and renders to some of the real elements we captured. The “wall of rain” in the nighttime encounter over the house was challenging. It was like simulating a circular waterfall around the house since the saucer acted like a giant 240` wide umbrella.

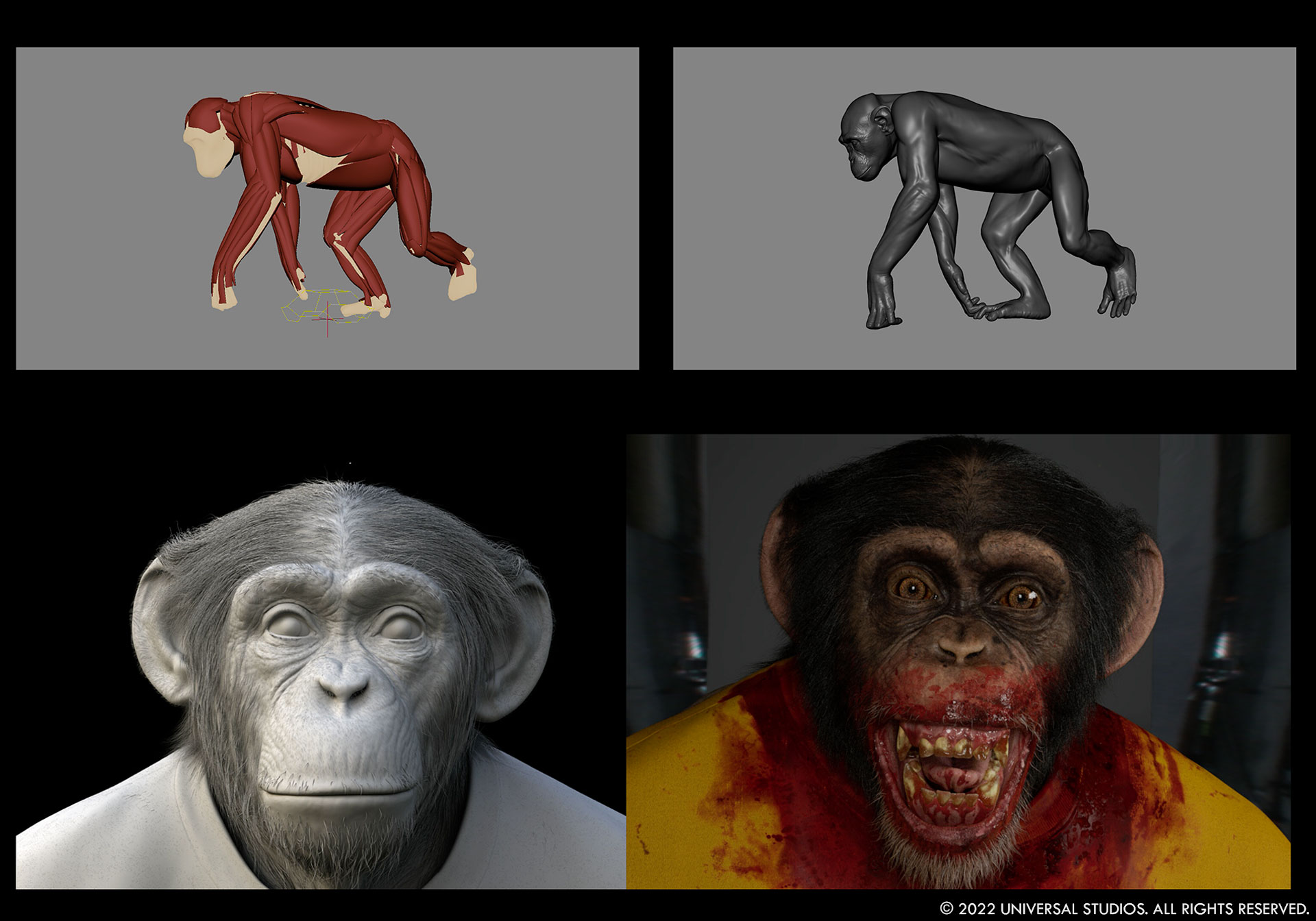

Can you talk about how you created the terrifying scene featuring the chimpanzee, Gordy?

Because of the horror nature of the scene, it was really important that we could shoot and design the scene as organically as possible. Terry Notary, who performs Gordy, is incredibly experienced with motion capture, but we wanted to give him a playground and props that were less sterile than a motion capture set and suit. We built a false perspective set, with everything 30% bigger around Terry so he could perform at the size of a chimp. The sofa, lamps, etc. were more significant, and a 6’2 stunt woman played the little girl lying on the floor. On top of that, Terry was dressed like Gordy, in full bloody makeup, even though we were going to replace everything with a dressed CG chimp down the line. It gave Terry all the tools to give us an outstanding performance, and it provided us with perfect references for how the clothes, gore, etc., would need to look when re-created in CG.

The scene is seen under the table from little June’s point of view. Playing with our idea to create a certain level of Obscuration we established with Jean Jacket, Jordan had the idea that we should mostly witness the scene through the semi-transparent tablecloth hanging from the table in the foreground. So, our CG chimp always had to be processed to diffuse through the silk fiber, which made our Integration work particularly challenging.

Gordy itself was created from multiple photographic references we looked at of “Hollywood chimps.” MPC’s Character Lab created a very high-resolution asset; the clothes, gore in the fur, and eyes were a particular focus to convey Gordy’s changing emotional state. On an IMAX screen, when Gordy sniffs the tablecloth, he is literally as big as a full-size King Kong that would stand in front of you.

Did you want to reveal to us any other invisible effects?

To suggest the looming presence of the sky, you’ll notice that there are always cloud shadows driving on the ground. We applied that throughout the film whenever the clouds were above us, even in scenes where there was no encounter with Jean Jacket.

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

There is a long continuous shot where Jean Jacket comes down towards OJ and the stadium. You follow Jean Jacket slowly approaching in the clouds without ever cuffing, all the way to the abduction attempts right over us. This was a beast to design and render!

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

I would say, strangely, that I had a few short nights thinking about the clouds and how important it was that they never stood out as visual effects. It was the foundation of a lot of our work in terms of shot design, etc., throughout the whole film.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

I am not really able to pick one, but I am glad to see that we figured out how to integrate our minimalist saucer and Jean Jacket photographically. Lighting, dust, clouds, etc. It took many elements to get right. The night scenes using our day-for-night technique, I think, are pretty special too.

What is your best memory of this show?

There are a lot of great memories making this film. The collaboration between all the departments and Jordan is what stands out to me.

How long have you worked on this show?

Almost two years.

A big thanks for your time.

// Nope – Final trailer

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

MPC: Dedicated page about Nope on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2022