In 2020, Adrian de Wet and Eve Fizzinoglia talked to us about the visual effects on the first season of the See series. They then took care of the effects for Slumberland. Today they tell us about their work on the prequel to The Hunger Games.

What is your background?

Eve // I attended film school at Emerson & spent 10 years in episodic producing before starting in features.

What was your feeling to be back in The Hunger Games universe?

Adrian // Catching Fire and Mockingjays 1 & 2 hold fond memories for me, so it was great to be back in the dystopian world of Panem with Suzanne Collins’ compelling characters. I love world-building projects, and this is a new take on a previously established universe, which of course comes with new challenges.

How was this new collaboration with director Francis Lawrence?

Adrian // Francis is a great collaborator, and as is always the case with his projects, everyone is encouraged to bring ideas.

Eve // Planning big VFX sequences with Francis is a great experience. He is thorough, has a clear vision with story as the foundation, and his support for our process allows for more detailed refinement of the final shots in the end.

What are the main changes he wanted to do since The Hunger Games movies?

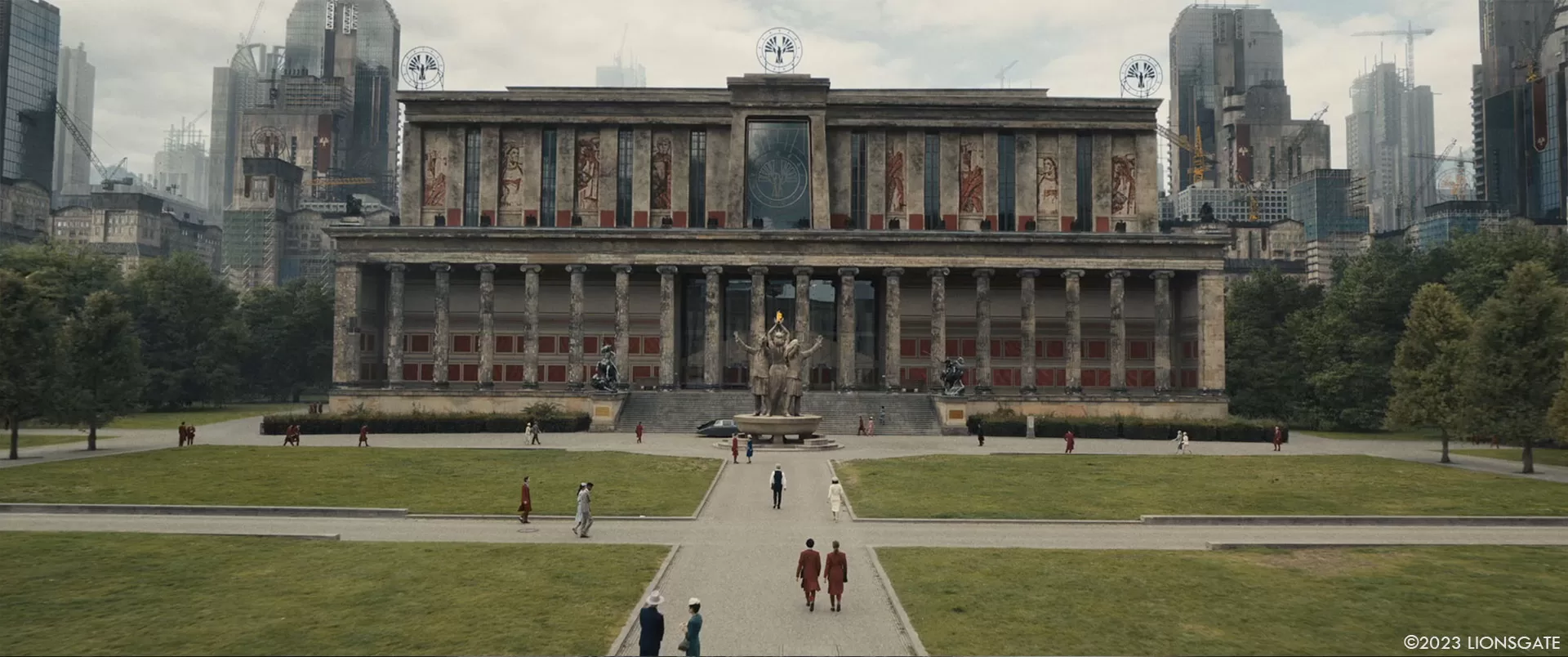

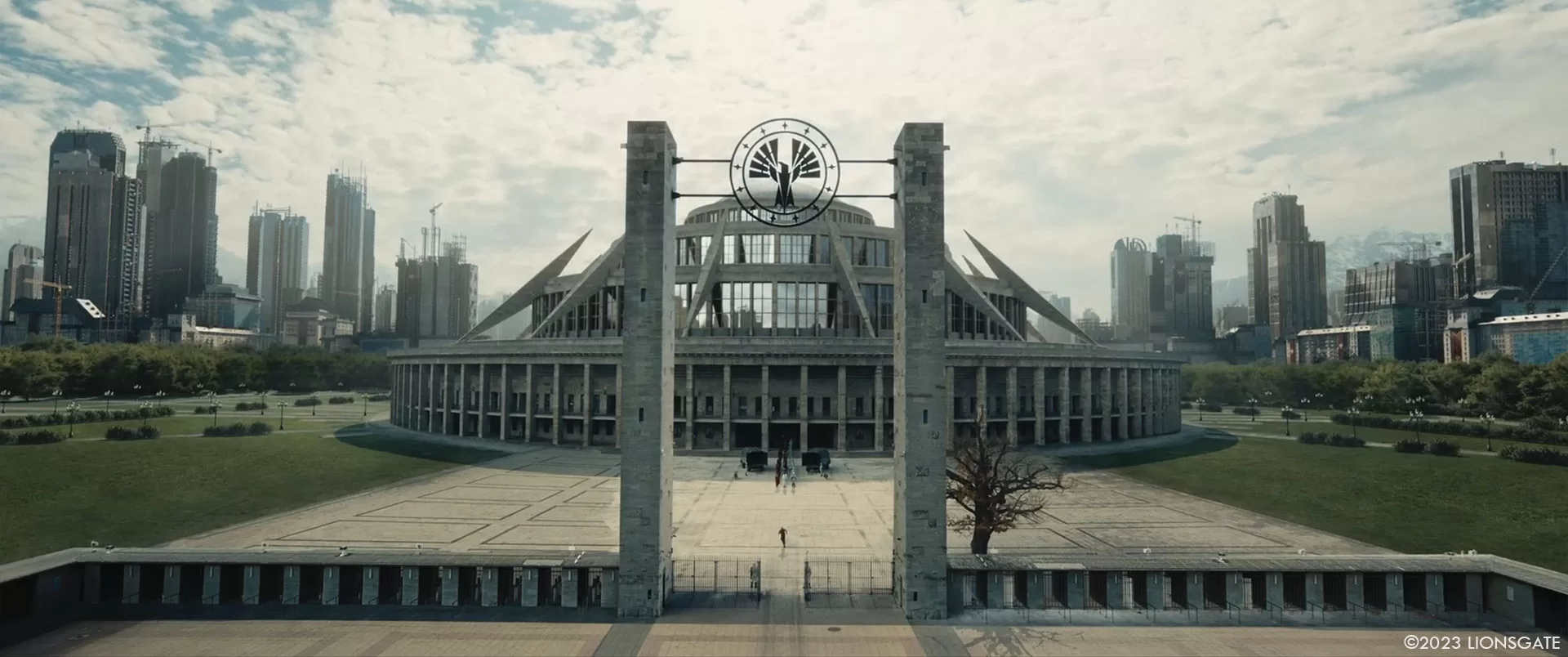

Adrian // Most importantly, this is a period piece, set 65 years before the events in the original Hunger Games movies. So, there is far less future-tech: no flying hovercrafts, and instead of a vast holographic arena with scoreboards in the sky, the spectacle of the « Hunger Games » – a much cut-down but still brutal version of what came later – takes place in an indoor Arena partially destroyed by bombs. And as for the Capitol itself: instead of a city made of gleaming towers, with grandiose ceremonial avenues and high-speed rail, our dystopian metropolis is in its “Reconstruction Era”, with bomb damage from the war still visible, the skyscrapers in a state of incompleteness, construction cranes and scaffolding defining the skyline as the Capitol rises out of the ashes of the war.

How did you organize between you?

Eve // The work is split traditionally, with Adrian managing the creative & technical direction, while I take on more of the organization & planning. But we collaborate on all aspects of the project, strategizing major decisions together, and providing support for each other’s roles. Adrian is an experienced and visionary VFX Supervisor, so the creative trust is an ideal starting point to focus on how to get the images on the screen.

How did you choose and split the work amongst the vendors?

Eve // This is like assembling a puzzle, and it starts with the first script draft. We section the film into sequences based on category of work, and by the technical specialties of the teams we know we want to include. Building the shot distribution plan is exciting because it sets the workflow for the whole film, and it’s the first step to seeing it all come together.

Where were the various sequences in the movie filmed?

Adrian // The Arena scenes were shot at Centennial Hall in Wroclaw, Poland, and the lake was in southern Poland. Everything else was in Germany. The Capitol locations were all around Berlin, and District 12 was filmed at Landschaftspark in Duisberg. Our on-set supervisor, Sean Stranks also shot plate elements for the countryside train traveling in Germany.

What was your approach to create this new version of The Capitol?

Adrian // For the environments in the previous Hunger Games movies, we always shot at locations which had something in common with how the environment should look in the final film. This movie was no exception. For the Capitol, we decided to shoot at locations in Berlin and augment them – even if it meant that a significant part of the background would be replaced. The big difference this time around is that this new – or rather, old – version of the Capitol is a much more old-world, retro version of what we designed for Catching Fire and Mockingjay 1 & 2.

Can you elaborate on the creation of the various environments of The Capitol and District 12?

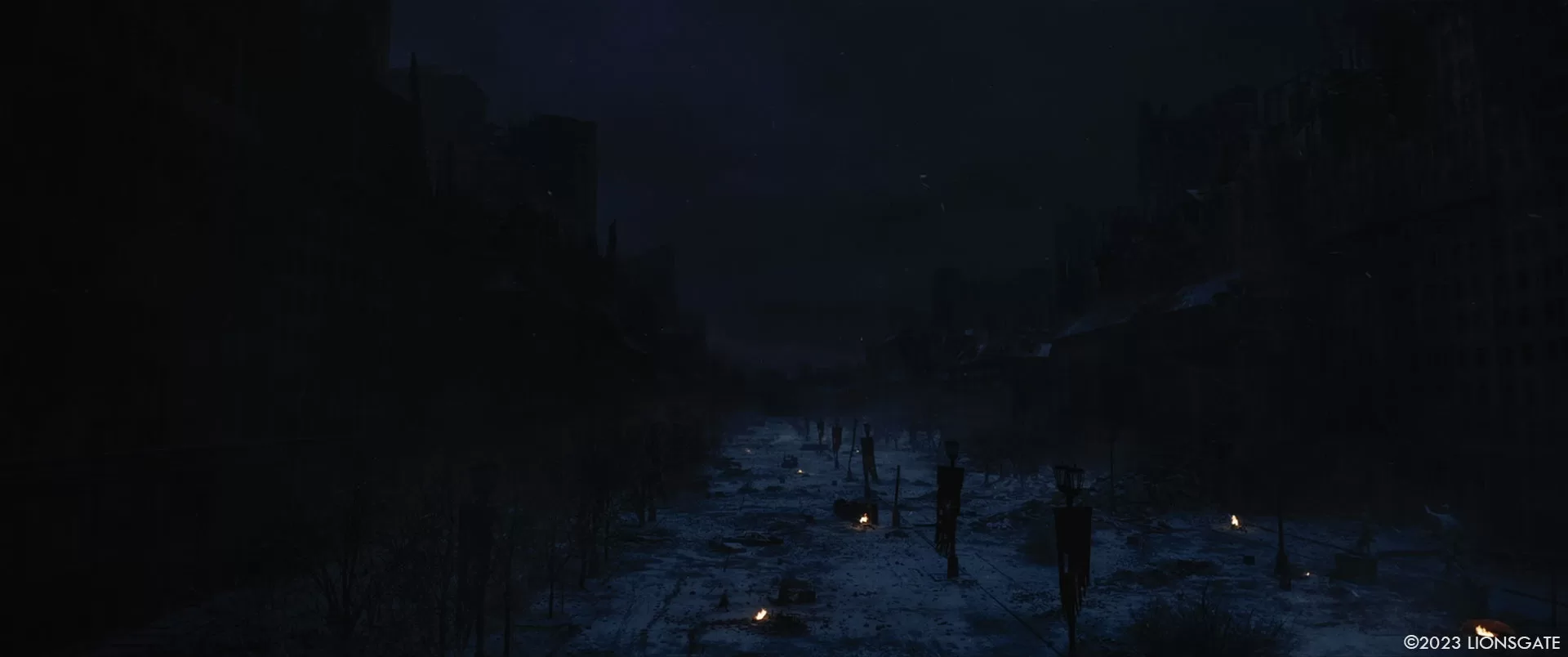

Adrian // The scenes in The Corso, where we see Snow walking towards the fountain with the huge statue of Panem, were filmed in Karl Marx Allee, which is a wide-open boulevard in the former East Berlin. We changed a lot of the buildings by extending them to twice their original height, and added new facades and aged textures, cranes and skyscrapers under construction in the background, and the statue in the middle of the fountain was added, complete with bronze verdigris textures and digital water spray from the fountain. We also needed another iteration of this environment for the opening of the film which takes place ten years prior – during the height of the conflict, where the buildings are abandoned and half demolished, and the street is covered in snow.

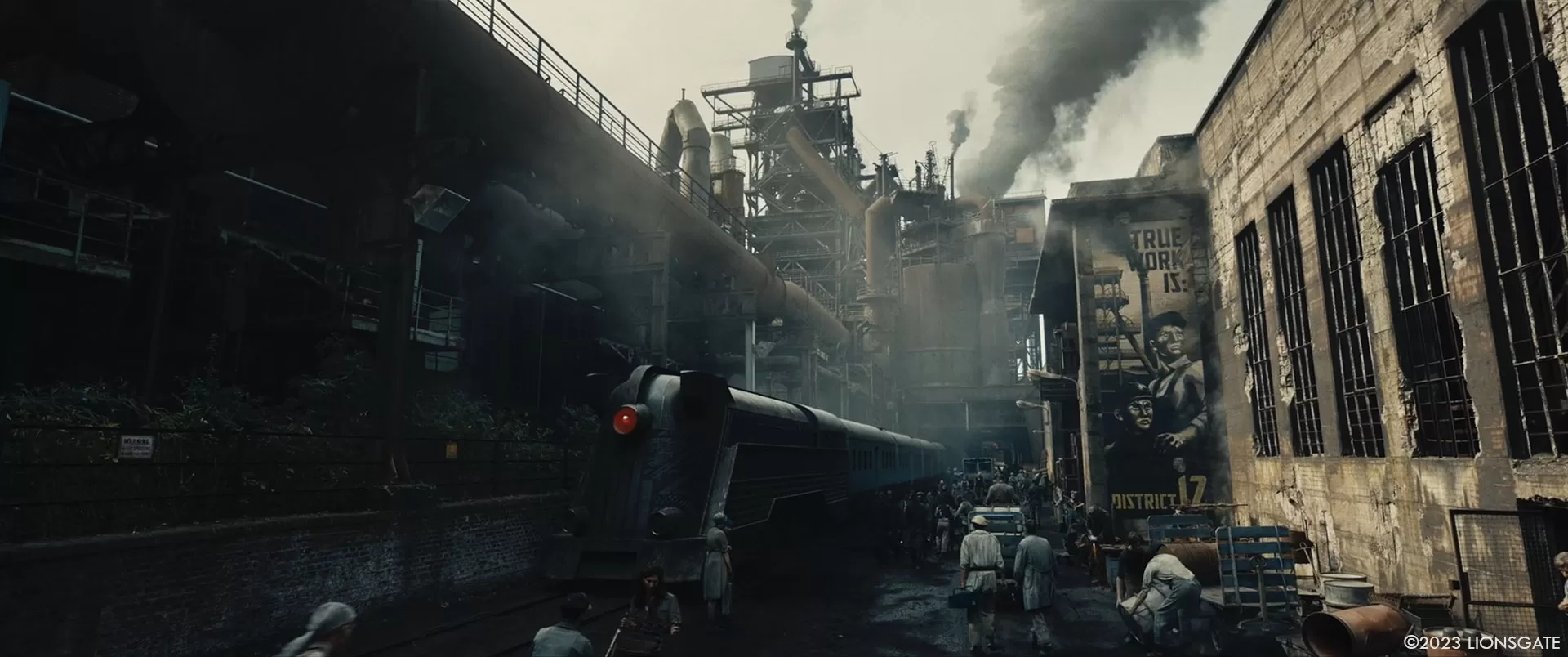

For District 12, a similar approach was used. We shot scenes at a location called Landschaftspark near Duisburg in West Germany, which has real industrial structures. The team at RISE digitally extended environments and buildings, but the most complex vfx work was the addition of the train arriving from the Capitol – an art-deco influenced CG train hauling passenger cars which Snow and Sejanus disembark as it comes to a halt. For this, we built a partial set (basically the carriage door) and RISE built the CG train around it.

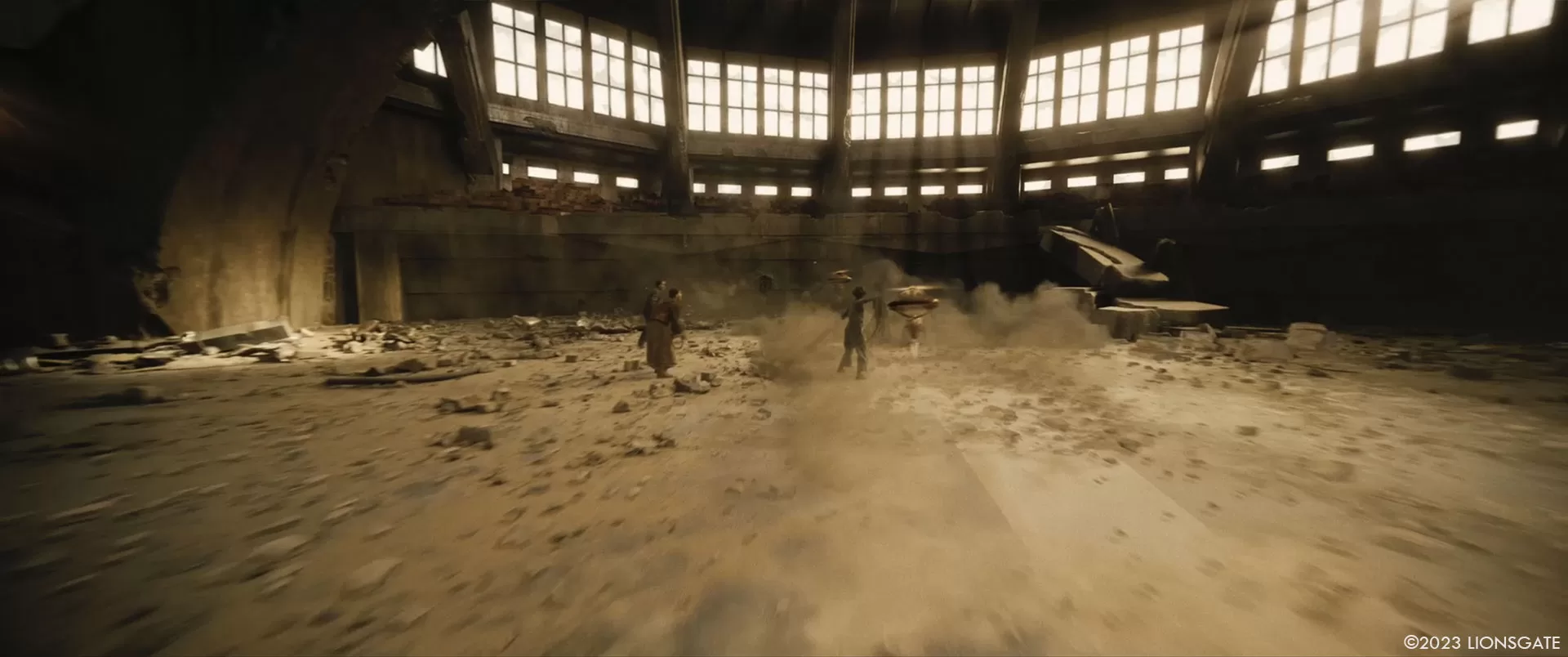

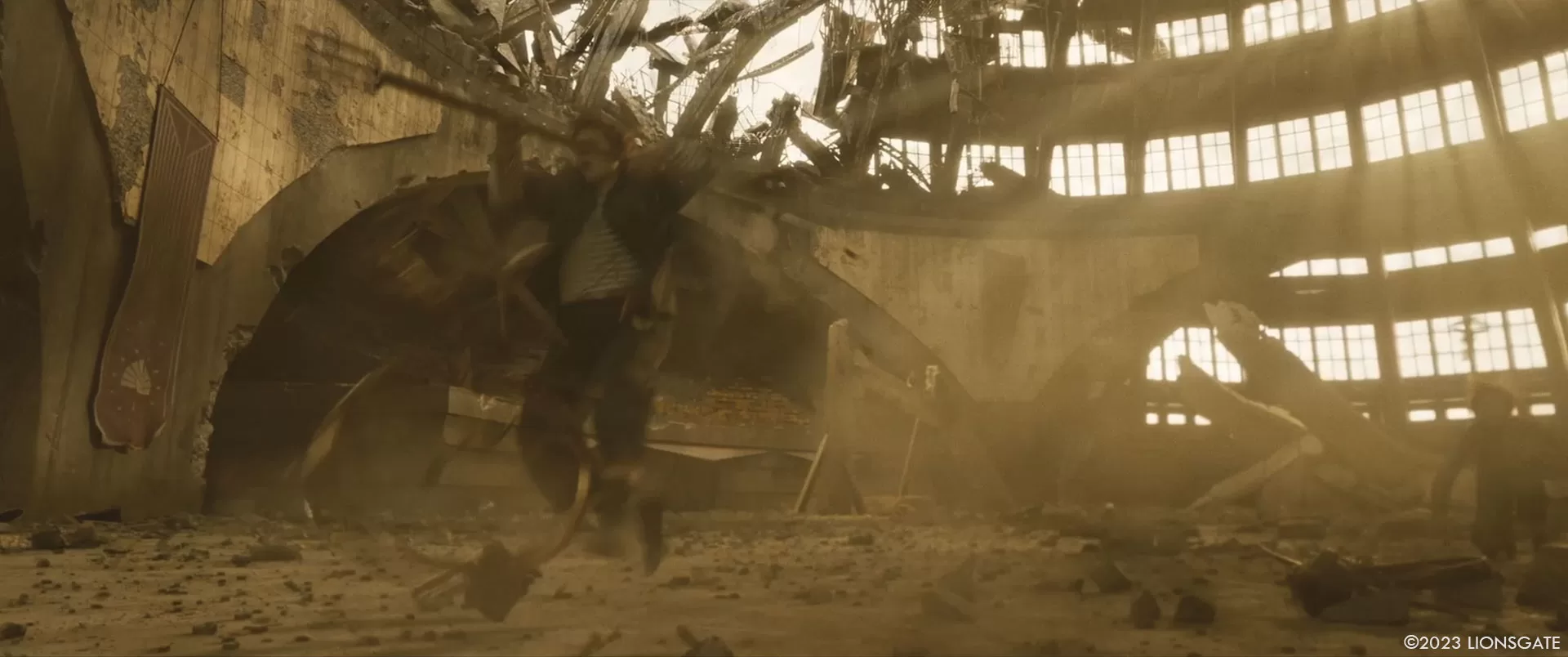

Can you tell us more about the Arena destruction?

Adrian // The Arena Bombing scene was a successful collaboration between VFX, stunts, SFX, and lighting. We previz’d and tech viz’d the arena bombing to get the camera moves, the locations and timings of each explosion down. On set, reactive lighting was used at the location of each bomb to provide a short-lived flash. The SFX department provided air-mortars to blast air at the actors in time with each bomb. In the CG world, Important Looking Pirates (ILP) modeled the large concrete debris based on the position that they had to end up in for the rest of the film, and reverse-engineered them to fall from above as the ceiling collapsed. We also shot stunt elements of mentors and tributes being blasted by the explosions. ILP provided everything else: fire, smoke, flying debris and glass, the destroyed arena walls, and the falling piece of concrete which pins Snow to the floor.

Which location was the most complicated to create?

Eve // There were nearly 500 shots in the Arena throughout the Games sequences, requiring a challenging shared workflow between 4 teams who collaborated brilliantly with each other. The destruction was designed by ILP based on their explosive Bombing sequence, with additional ceiling damage by Outpost, walls & ground debris enhancements by RISE, and further details by Ghost.

Can you explain in detail about the drones creation and animation?

Adrian // Outpost handled most of the drone sequences. The design is based on a practical drone from Art department – a brass colored, retro-looking old-world design. The challenge in animation was to get them to travel so fast that the characters couldn’t have avoided them, and they had to hit them so hard that they get knocked over, and at the same time be believable. On set, the choreography was designed by stunts, and everything was mimed, so we were locked into certain timings and speeds. This meant that the edit informed the animation, but then we had to speed up and alter the length of certain takes to get the animation to work, which meant the animation also informed the cut. We worked closely with our editor, Mark Yoshikawa, to get this right.

How did you work with the SFX and stunts teams?

Adrian // There was a lot of collaboration with SFX and stunts, especially in the Arena. The bombing sequence, and the drone attack, all had extensive stunt work. And later, at the hanging tree, with a lot of stunt rig removal.

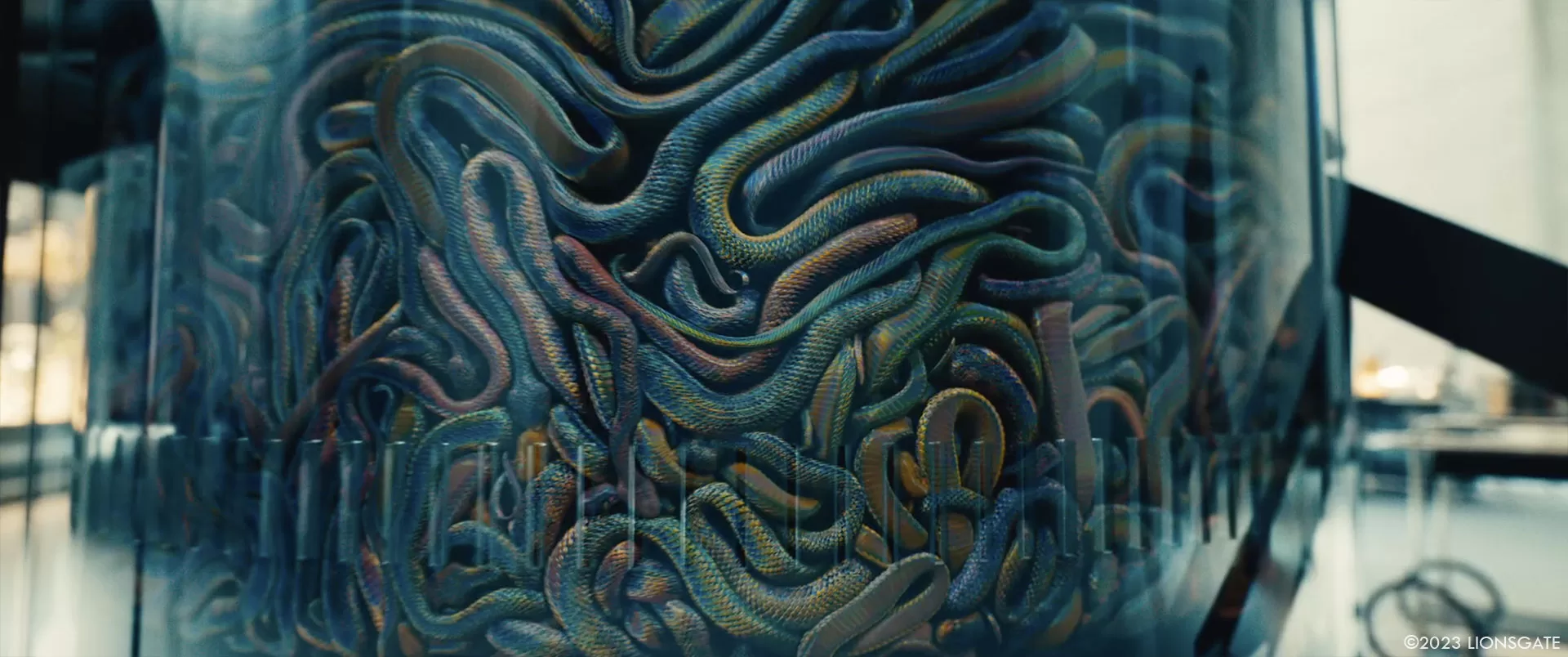

Can you elaborate on the design and creation of the snakes?

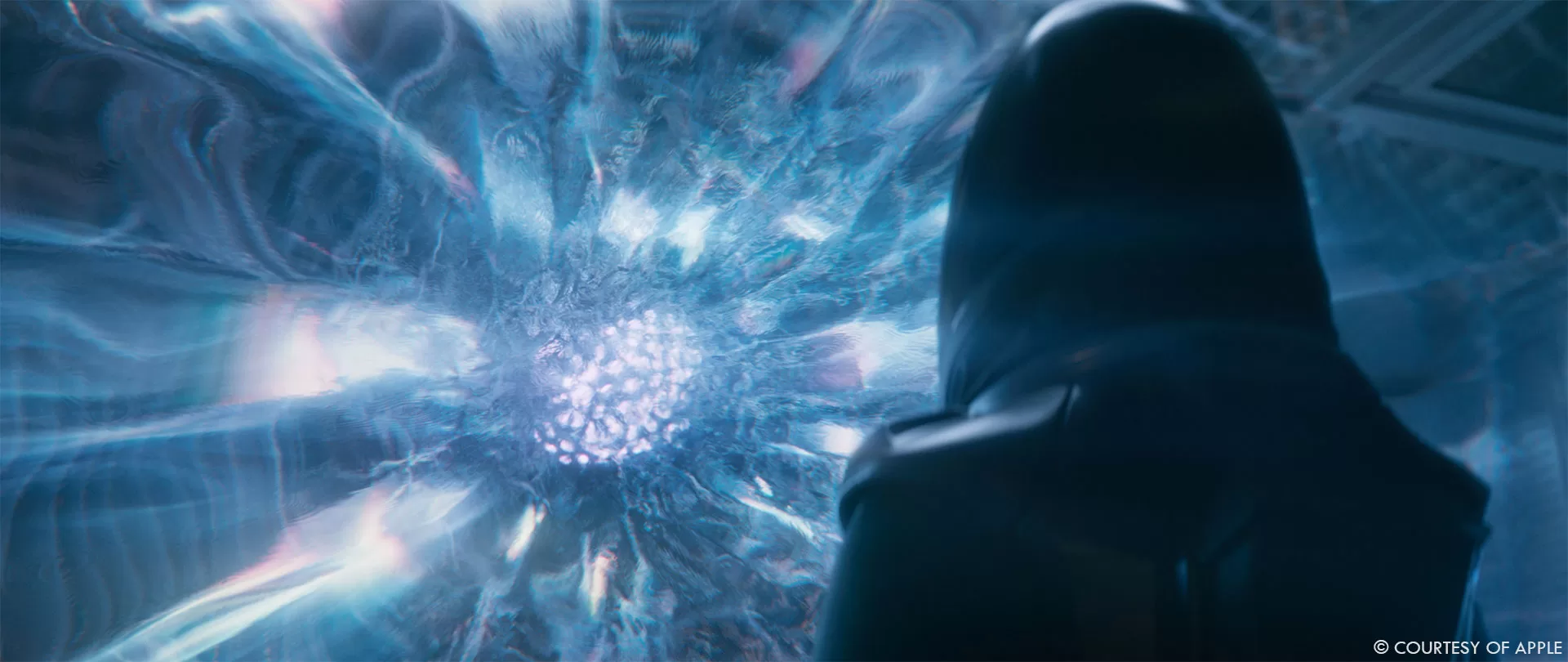

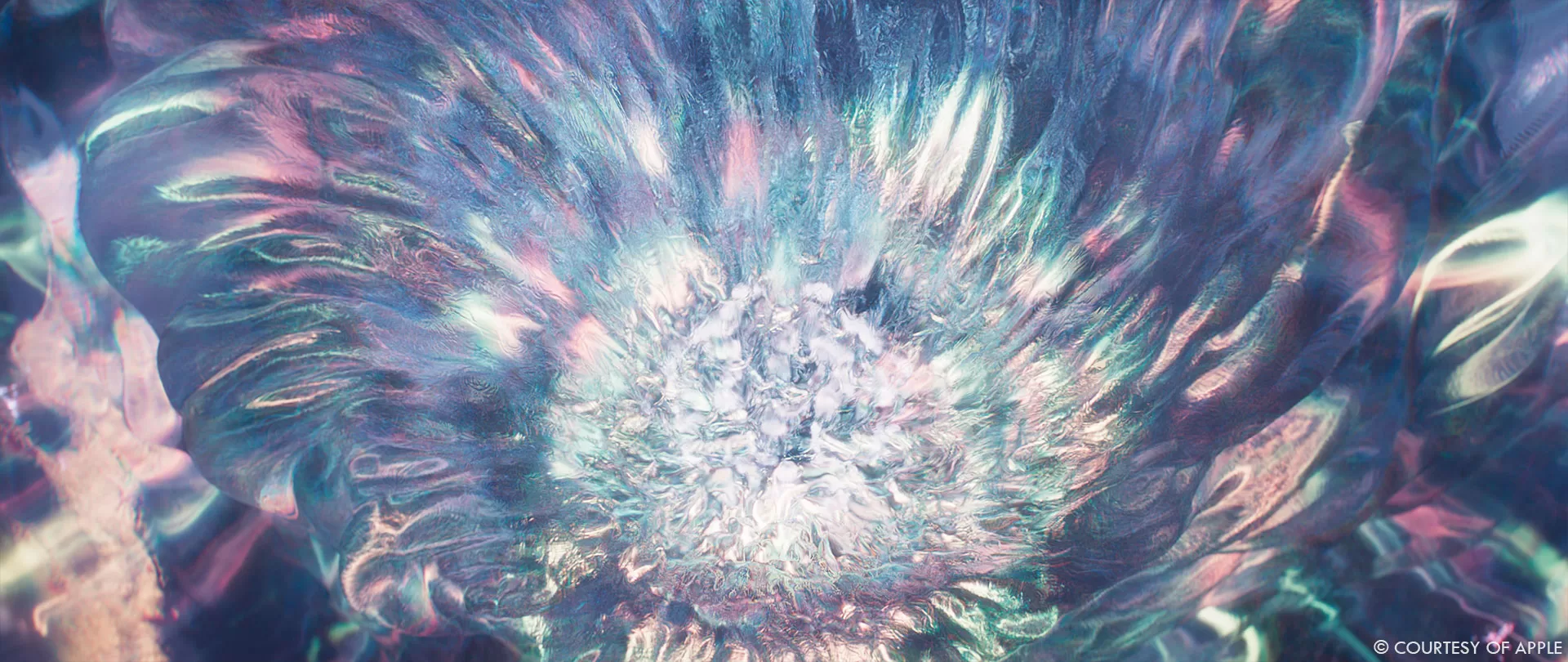

Eve // Francis and Adrian were keen to bring to life the mutant « rainbow » snakes as described in the book, while also keeping them grounded in reality. The snakes were created by the team at Ghost, using references of real snakes with iridescent skin, and extensive R&D and lighting techniques to bring out the colors in a natural way.

How did you manage their animations?

Eve // Working with the Ghost team a few times before, they knew that the goal for Francis and Adrian is always realism. They used real snake footage as reference for the animation, adding digital sand and gravel for the snakes to create trails, interacting with the environment as they move.

What were the main challenges with the snakes?

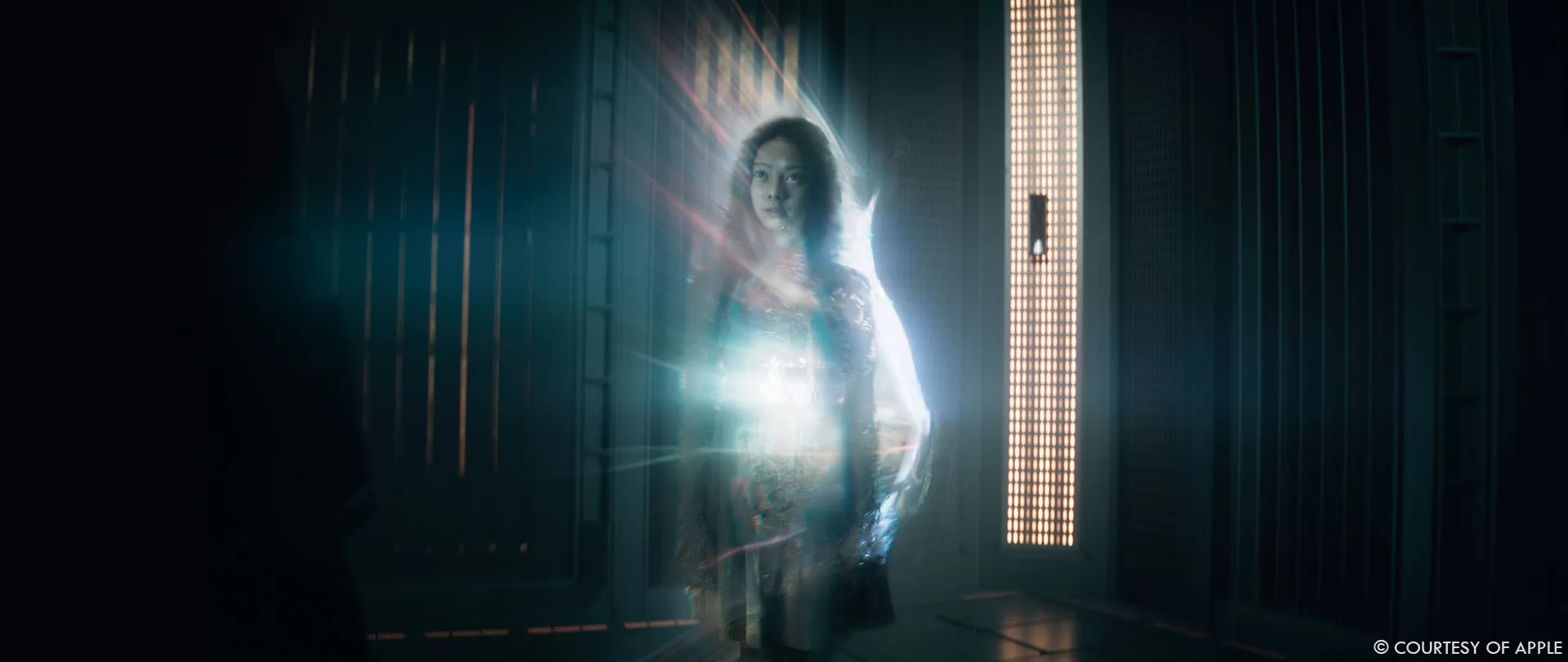

Adrian // Ghost handled a huge amount of swarm simulations when we see thousands of snakes, moving as a wave, hunting down their victims, but as the scene progresses, the swarms are gradually replaced by more detailed hero animation until only Lucy Gray remains. The biggest challenge was integrating the snakes into the fabric of her clothing – her loose-fitting blouse and long skirt were made of layers of chiffon and tulle. This fabric would have to move and twist and cinch as the snakes slithered over it and wound themselves around it, so we decided that the most effective way to do this was to replace her clothing with digital cloth. This was one of the most challenging sequences in the film.

Did you want to reveal any other invisible work?

Adrian // There was a lot of invisible VFX on this show.

All the content on the monitors in the auditorium is added digitally. We had live playback on the day, which was helpful for the actors, but the realities of editing mean that things don’t always end up in the order that they were intended during shooting.

In the early scenes when Snow is in the shower: even though actor Tom Blyth lost weight for the role, Outpost VFX made him a little more emaciated and malnourished than he really was.

The rabies foam on Jessup’s mouth was created by the team at Ghost, and the foam on the rabid dog’s mouth in the beginning was done by ILP.

The Hanging Tree: the trunk and the lowest branches were constructed practically, but everything above that is a digital extension, by Ghost, who also animated the flock of Jabberjays, which disperses every time someone is hanged.

All the birds in the film are digital. And the eels that writhe around in the small pond in Gaul’s lab

RISE extended the landscape of the peacekeeper barracks in District 12, adding hills and factories in the background and extending the Quonset huts.

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

Adrian // The snakes scene, as so much of the realism depends on the interactions with the fabric of her clothes, and we only get to really see this near the end of the VFX process, because it’s so time consuming.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

Adrian // All the VFX sequences in this movie were being handled by talented and experienced artists, and we have an awesome production team led by our amazing VFX Producer, so, even though the work was very challenging, I always knew it was resourced in exactly the right way to do it all properly.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Adrian // I think what I love most is what RISE, Outpost, ILP and Ghost did to the Arena. Some of the shot design in that location is just beautiful.

Eve // I love the forest at the end, when Snow goes crazy on the Mockingjays. (There’s so much brilliant photography throughout, it’s a great pleasure to work with DP Jo Willems.) Also, when the mentors & tributes first enter the Arena, and the bombs go off – ILP did an amazing job with that sequence. And the snakes crawling on Lucy Gray while she sings was an absolute highlight from the Ghost team.

What is your best memory on this show?

Eve // Filming in Wroclaw, Poland during the summer was fun! And while postproduction & delivery can be stressful, seeing the final film at the end of a long road is the ultimate drug.

Adrian // Seeing it all come to life. The Arena, the Snakes. And seeing the Hunger Games fans’ reaction!

How long have you worked on this show?

It was a year and 8 months from script breakdown to final delivery.

What’s the VFX shots count?

1460.

What is your next project?

We’re working on something exciting – can’t wait to tell you about it soon!

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

Oops, that’s 5! 🙂

A big thanks for your time.

// The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes – VFX Reel

// Trailers

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Outpost VFX: Dedicated page about The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes on Outpost VFX website.

RISE: Dedicated page about The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes on RISE website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2023