Gary Brozenich is a CG artist for over 25 years, he joined MPC while the studio only had a dozen artists. After working on numerous commercials, he joined the film division since its creation and will be in charge of CG on TROY and KINGDOM OF HEAVEN. He will be then VFX supervisor for films like THE DA VINCI CODE, THE WOLFMAN or CLASH OF THE TITANS. It is therefore natural that he talks about his work on the CLASH sequel: WRATH OF THE TITANS.

What is your background?

I studied traditional painting and illustration at The School of Visual Arts, NYC. I did further classical studies in New York before relocating to London. During this time I made a living as a modelmaker/sculptor/finisher. Through contacts in the traditional industries I became interested in 3D, it had so much potential. I started a company in London with a few others in the traditional modelmaking field to create photoreal CG imagery for advertising. We competed directly with photographers for all of our work. It was with Alias Wavefront software on Silicone Graphics machines in 1997 and I had never used a computer before, so it was a steep but brilliant learning curve. That company faded after 5-6 years and I went to work at MPC when we were about 12-15 people doing almost entirely commercials on the 3d side. Then film VFX hit London and me very hard at about the same time and I knew it was what I wanted to be doing. I have been a CG Supervisor and VFX Supervisor for MPC since then.

How was the collaboration with director Jonathan Liebesman?

Jonathan was great collaborator from the outset. He came into the show with very strong ideas of creature design and shooting style and methodology. We had seen his previous films and knew he had specific tastes and approaches that were going to create the base fabric of the film and that held true throughout. On our side I came into the project with strong ideas about what I wanted myself and MPC to bring and approaches I thought would help keep the big CG shots held within the grain of what he was trying to achieve. From the start both he and Nick Davis were open to our ideas would embrace them when they fit the bigger picture, and slam us with a tangential challenge when it didn’t. Which was great. « Whats a better idea? » was a phrase he would use often and he’d throw it to us to respond to, sometimes ours would stick and other times not, but it was a good environment. A lot of the crazier ideas came from Jonathan. The Makhai having two torso’s was his concept that took me a while to get my one head around, but once we had the plates and started animating I saw that it added a whole new layer to it. That same spirit of really pushing it and challenging us filtered into all the work.

What was his approach about visual effects?

Jonathan is very VFX savvy. I’ve never had a director ask me what tracking software I use before. He doesn’t overwhelm the process and lets us get on with our work, but he has a genuine hands on interest in the process and understands what he can do with it. Occasionally he’d do his own rough CG blockouts on plates-« postvis »-and sending it to me to save too much interpretation. Its something we are seeing a lot more with younger directors and it truly helps grease the wheels and lets you have a greater short hand both on set and in post.

How was the collaboration with Production VFX Supervisor Nick Davis?

Both myself and MPC have done many projects with Nick before. My first CG Sup role was with him on TROY so our working relationship has spanned a number of films and years. He is always fantastic at keeping the creative barriers open for myself, the artists and animators to contribute with and through him on every film. He brings a huge amount of experience to his projects creatively and technically. He also took on Second Unit directing so his imprint was significant on WRATH. Both he and Jonathan were open and receptive to our input, but would often counter with something bigger. A healthy balance for the show and to ensure their bigger picture was coherent.

What have you done on this movie?

The primary creatures and sequences were the opening dream sequence, the Chimera attack, all of the Pegasus work (both wing additions and full CG) and the final battle after Kronos breaks from the earth, releases the Makhai to fight the humans on the ground and sees his demise. Mixed in there is a lot of one off work, like the gods dying and dissolving, full CG temples and set extensions and a number of DMP’s and others scattered throughout. A lot of creative challenges.

The movie features lots of creature. How did you proceed to manage their interactions with the locations and the actors?

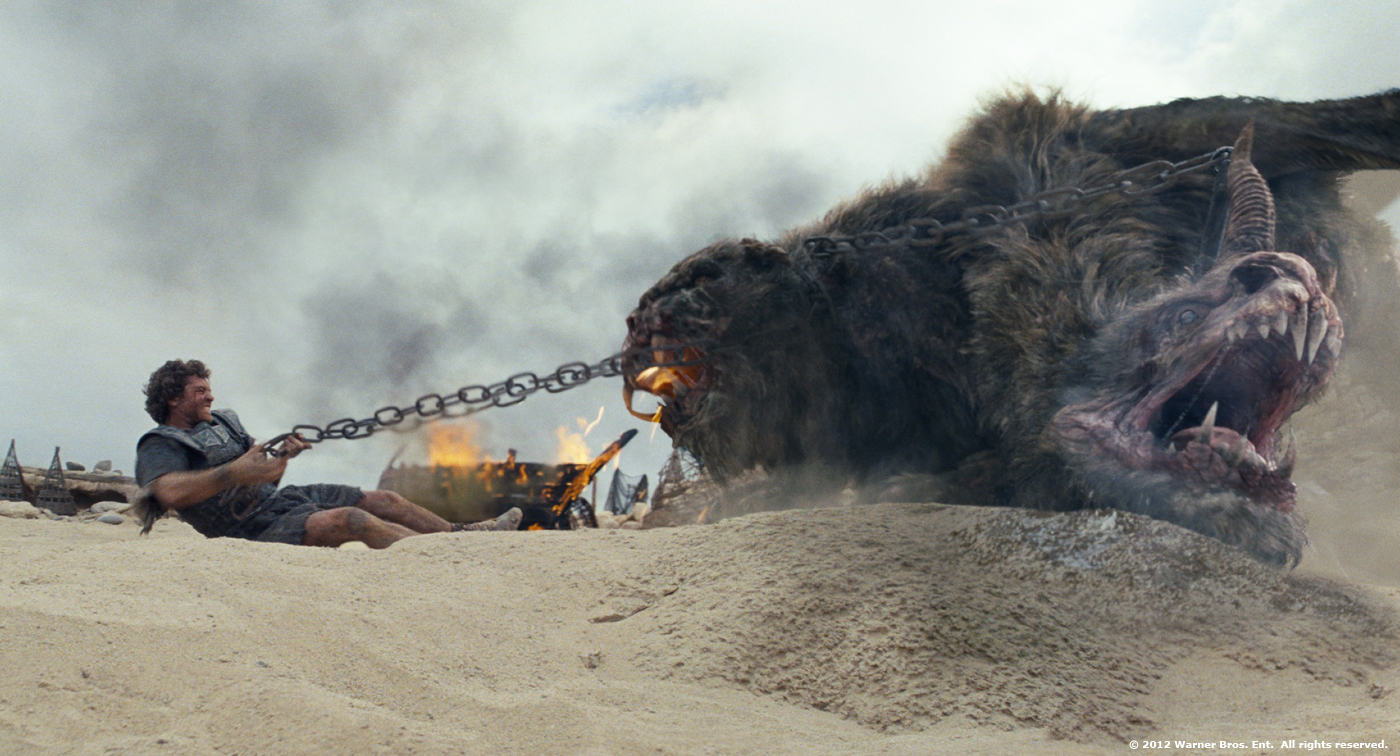

Each one was handled in a different way and often differently on each set up. It was one of the first issues we started to tackle with Nick. Nick was aware in pre-production that JL had a style and a shooting approach that was going to be gritty, hand held and in the trenches. Charlie the production designer was creating an arena for these creatures that would force the actors and stunts to face each other- no matter what. Tight corridors that had to fit a Rhino size creature and ten humans was going to guarantee they would be thrown, trampled or killed.

So we started in pre-production discussing approaches with the stunts, SFX and Nick how to make this look as earthy and integrated as everything else Jonathan was aiming for. The Chimera was too big, fast and agile to have a proxy or « man in suit » to stand in on most occasions. We did have liberal use of SFX wall explosions and kickers positioned around set timed to go off on his path. At first I was unsure if this would cause trouble in post- that we would be too bound to these and it would inhibit the animation too much. On some shows I would opt for adding it all ourselves, but with Jonathans style in mind we would typically go for the plate with the most grit in frame.

The Chimera sequence is pretty intense. Have you create previz to help the filming and to block the animation?

Some of the key shots were heavily pre-vised for technical planning. There was a cable cam brought in for one particularly long shot and that required a significant amount of planning and rehearsal. This shot specifically « stuck to the plan » in terms of the shot by shot methodology of the sequence. There was a geographical layout for the sequence as a whole and the FX breakaway and destructible walls were layed out accordingly. The primary action events were established, but, largely the structure, framing and action was recreated through JL and Sam as the shooting progressed and unfolded.

Can you tell us more about the Chimera creation and its rigging challenge?

The creature was largely designed in pre production before we picked up the sequence. There is a classical idea of the beast that the production stayed true to. The fleshing out of it was the biggest challenge to us. Making it belong not only in our world, but in the visual world that JL was creating for the film. Mangy, dirty and diseased were the major themes but preserving its power. It had to feel like a neglected and battered creature from the darkest wild. The challenges for Anders Langlands (CG Sup) and the rigging team was something we had to face a few times, an anatomical split in a creature that would need to be weight counter balanced by the rest of its body. The trickiest issues were where to place the split in the neck, how far back on his spine would feel natural, how to proportion the rest of the anatomy to compensate for this and how to gracefully handle the interpenetration issues arising from two heavily mobile portions occupying the same anatomical space. These issues were dealt with very effectively and very early on with range of motion studies with Greg Fischer and his animation team.

What were your references for the Chimera animation?

Lions. Particularly a few clips where they attack humans. Nearly every move he made was based on footage we could source.

How did you manage the fire thrown by the Chimera?

It was always a combination of FX and LA flame thrower elements. The creature actually emits an atomized spray from the goats head and a heated vapour from the lions head who’s combination creates the fire. We started each shot with FX elements created through both Maya and Flowline and detailed it or bulked it out with actual flame thrower material shot as elements.

What are the modifications about Pegasus between the previous movie and this one?

It was primarily upgrading existing assets to the latest versions of in house software. Primarily our groom tools that we call Furtility. Also, the horse was less kept looking than in the first so we added longer fur around the hooves and roughed him up a bit.

Can you tell us more about the Gods death that turns them into sand?

Originally it was only Poseidon that had this effect, but as shooting progressed it was applied to all of the gods. Shots were matchmoved and the actors were roto animated to their performances. We did not marker them up as we did not plan do so many or for them to be delivering dialogue during the transition between states. We created models to match the actors at the time of the shot, but obviously needed to deal with a more sculpturally designed version of their hair. The actual destructive process was created using Kali, which is an in house creation for shattering and rigid body simulation with a simultaneous geometry creation/extraction. Once the Kali effect, which gave us the gross collapsing effect, was approved it was the used to drive a more granular particle simulation that gave the sand like appearance. Likewise the initial model that was Kali’d was used to spawn a surface of particles that inherited its colour from the textured and dmp-projected geometry and that served as the rendered hard surface for the actor. This was then introduced in a patchwork across the performers face and clothing through judicious work in compositing using Nukes 3D and geometry capabilities. In some cases whole sections had to be retracked and warped to contend with the changing topology of their faces as the delivered lines.

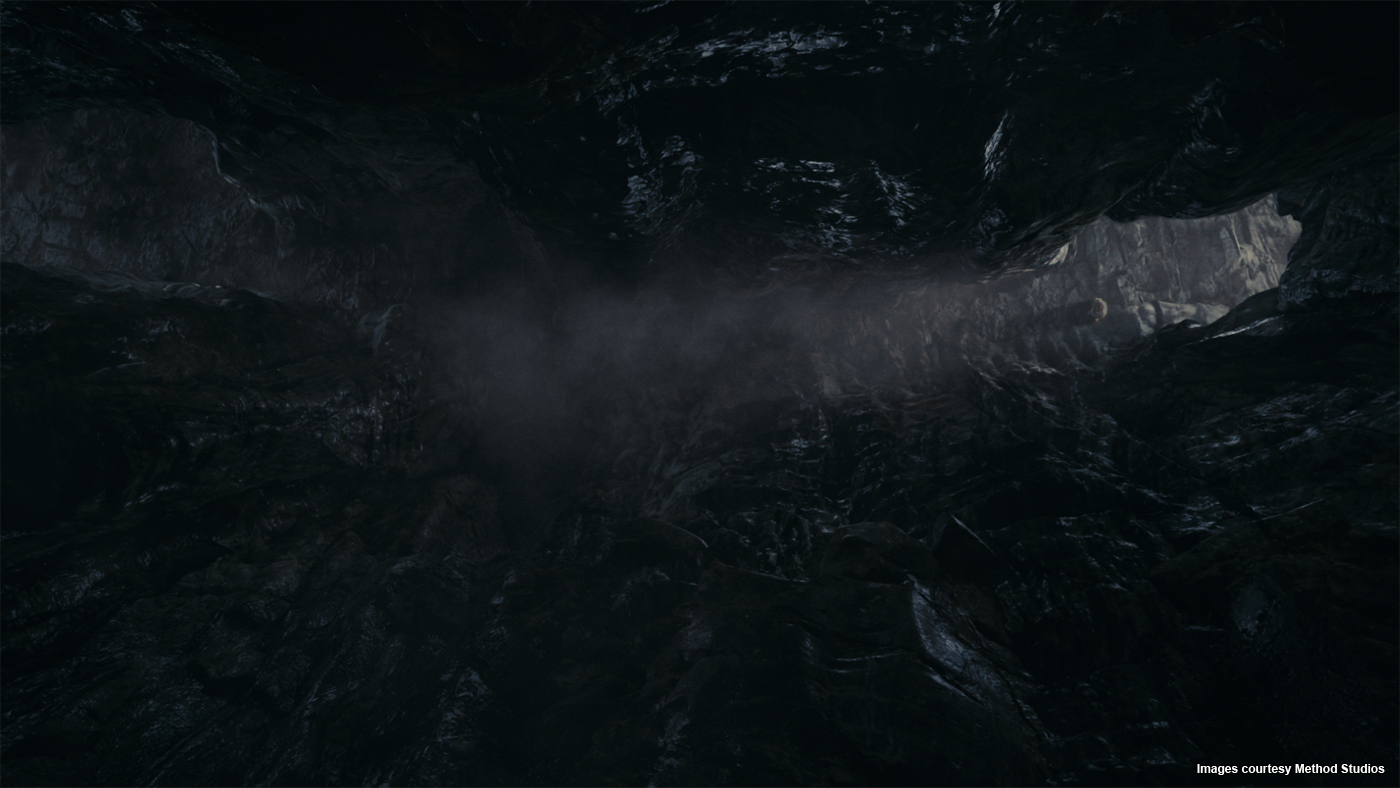

How did you create the huge environment for the final battle?

It was a combination of plates from two primary locations Tiede National Park in Tenerife and a very different looking battlefield specific location in south Wales. For the initial eruption and the path of destruction that Kronos lead I did several weeks of shot specific aerial photography over various volcanoes and lava created terrain in Tenerife. Nick Davis and I discussed the shots extensively and I shot a number of iteration of each in a few locations to give Nick and JL the material that they would need to cut with. So to answer your question specifically – we tried to shoot all of it, even if we knew it would be reprojected and altered significantly in post. I am a very big believer in having a plate to anchor work into whenever possible. Even if you deviate significantly from it in the final execution of each shot, which we did, it will give the editor, director, supervisor and all of the artists an inherently realistic core to spring from. Following the shoot Nick and I limited our suggested selects for JL and he and the editor cut with those. To aid the process I thumbnailed the storyboard or previs image onto the corner to remind them of the intended composition once Kronos was in the shot. This was sometimes taken on and often a better alternative or a new shot would rise through the cutting process.

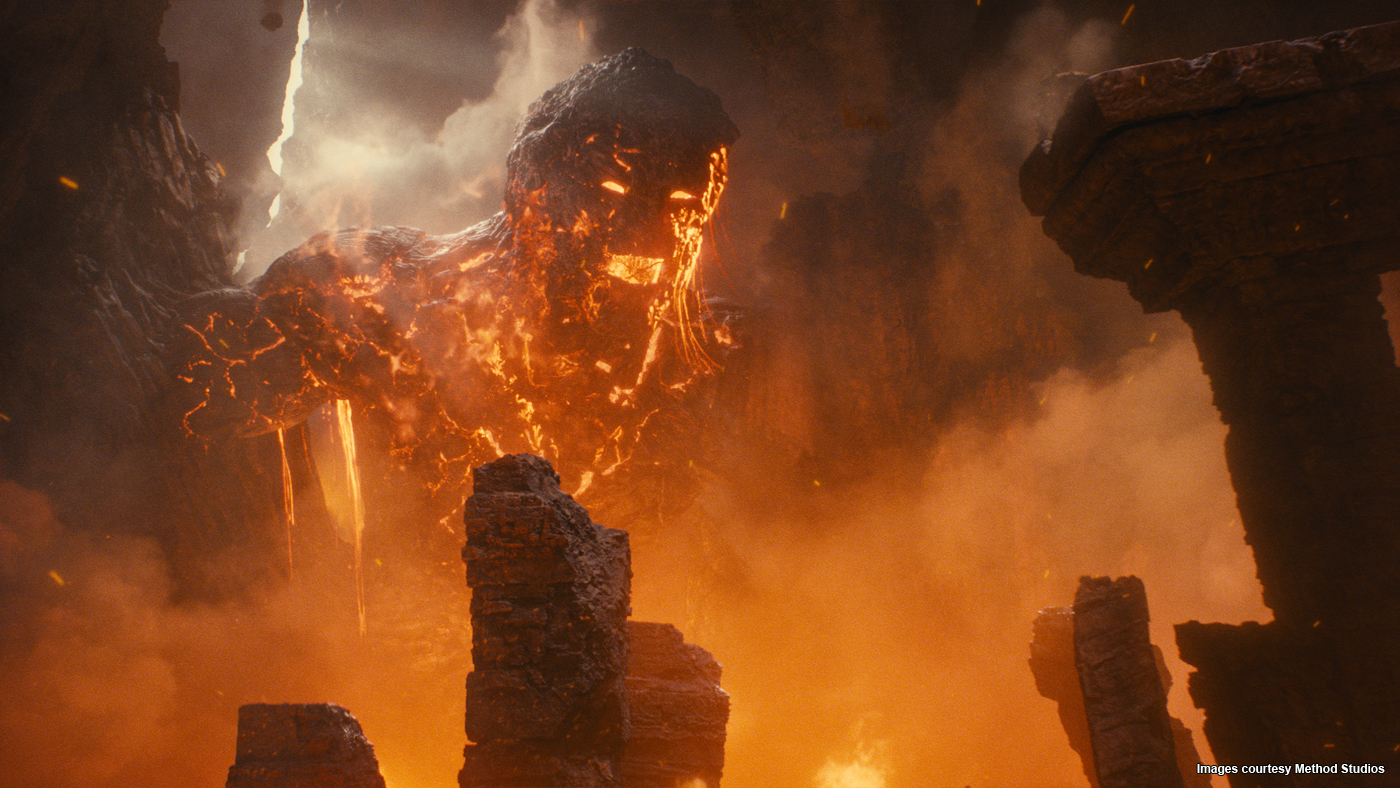

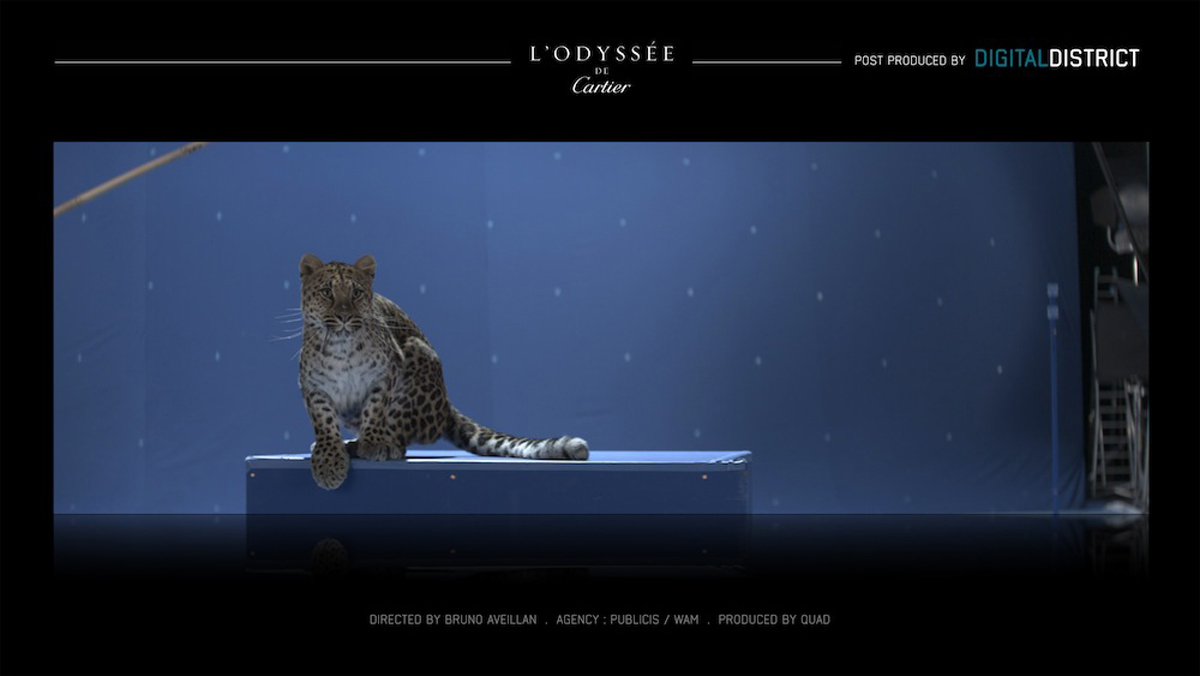

The Makhai are impressive creatures. Can you tell us more about their creation?

The design process began at MPC with Virginie Bourdin and our Art Department. Nick had given them an initial brief and we were entrenched in making these tortured creatures that had to have the size strength and presence to emerge from a volcanic rock, but not be too large that they could not fight hand to hand with a human and also be killed by them. The scale of Kronos precluded him as a viable option for a good punch up and Nick and JL needed a scaled opponent to keep the humans occupied and the action flowing in the scene while Kronos made his way to the location. We had a number of sessions and thought we were honing in on a solid design when JL threw us a total curve ball that he wanted them to have multiple arms and two distinct torso’s and heads. For a while we had a hard time getting the idea straight in our minds and how a character like this could fight, but more specifically how it would emerge, run and navigate very complex terrain on its way to the fight. We simultaneously worked it in concept and as a rough rigged model so that we could do motion studies as the design matured to ensure it would function all the way through the film.

Does their double body aspect causes you some troubles especially on the rigging side?

Absolutely, similiar to the Chimera but with much greater range of motion due to the anatomy and location of the split. It was a great challenge for Tom Reed our head of rigging and his team to confront. Many iterations and clever solutions to conceal and embrace the issues as features created the creature that’s on the screen now.

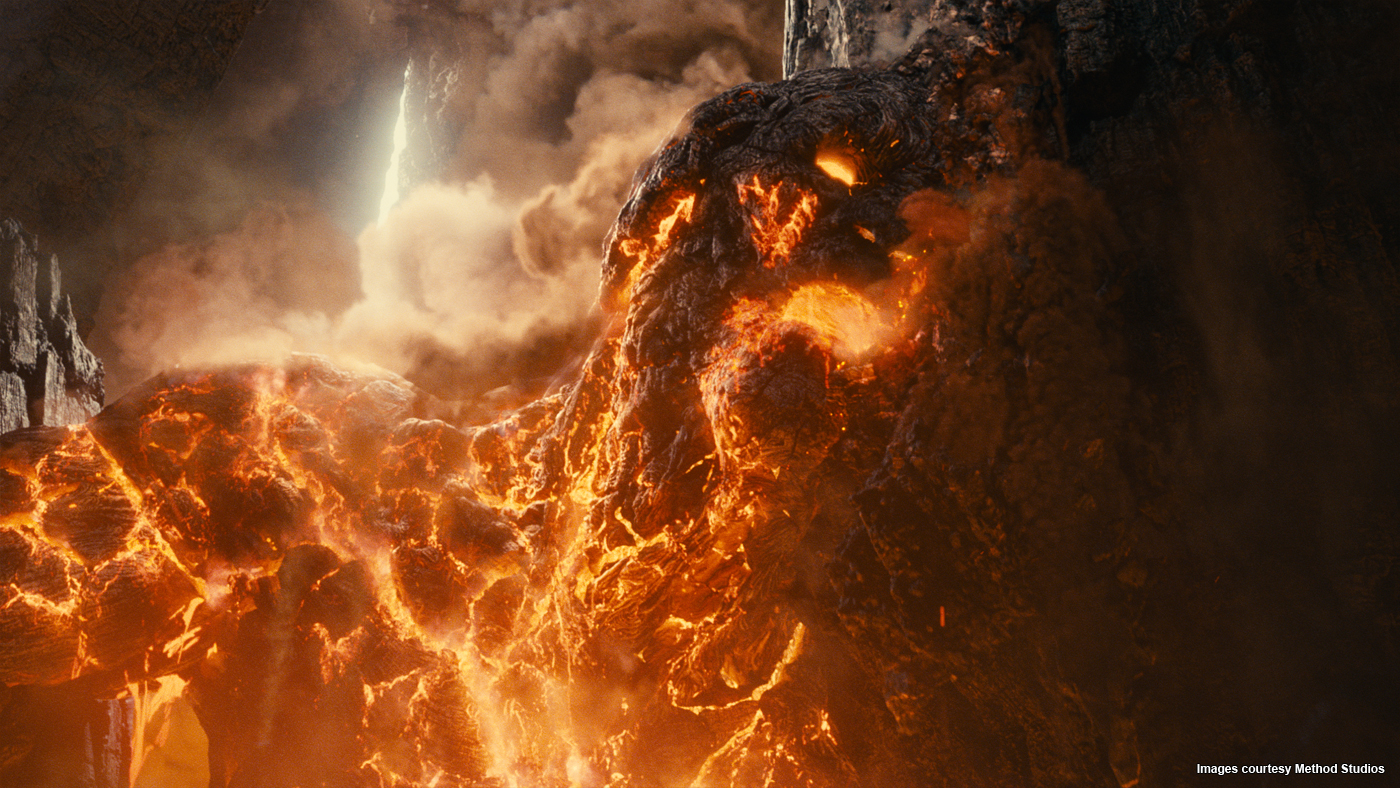

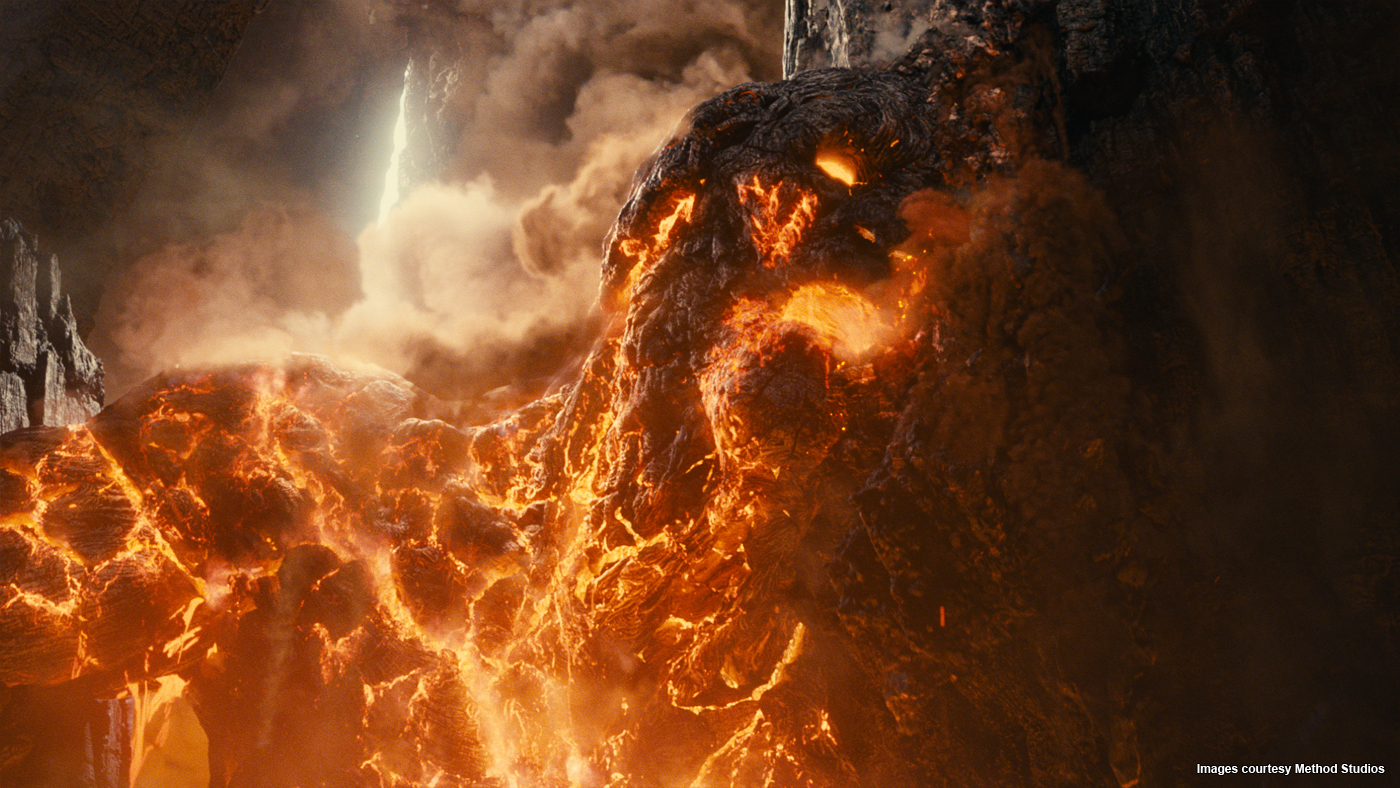

The Kraken was a huge challenge on the previous Clash. For this new Clash, Kronos is much more bigger and complex. How did you faced this new challenge with its amount of FX and particles?

The major difference between the two challenges was the variety of material required to bring Kronos up and move him forward. The Kraken emerged from water and was constantly dripping water which at that scale quite quickly turns to mist and streams.

The step up in complexity for Kronos was huge. The most difficult part was probably the smoke plume that trails out behind him as he lays waste to the battlefield. We split the plume into two main sections: the main plume behind him, and what we called the « interaction plume », that was directly tied to his body. The main plume itself was simulated in 50 caches that were re-used from shot to shot. Each of those caches was several hundred gigabytes a frame. The interaction plume was simulated bespoke for every shot since it tied directly to Kronos’s animation. That consisted of a thick, dense plume coming from his back, and many smaller smoke trails coming from cracks in his surface. By carefully placing and layering these elements we could create the effect of a single, massive eruption of smoke. We then layered on lots of live-action smoke elements in comp to complete the effect.

All the fluid simulations for the smoke were done with Flowline, and in many shots totalled terabytes of data per frame. In order to handle this we wrote a new set of volume tools to allow us to manage and preview the scenes without running out of memory, then to stitch these all together efficiently at render time. Even so we had to split the smoke out into many render layers in order to be able to get it through prman.

As well as the smoke, Kronos is constantly streaming lava and breaking off chunks of rock from his surface. These were handled as separate particle simulations using Flowline for the lava, and PAPI, our rigid-body solver, for the rocks. Again, these effects were made up of many caches rather than being done in one for speed and flexibility.

In order to bring all these separated elements back together in comp we made heavy use of deep images rendered out of prman to generate holdout mattes so that we could layer everything up in the correct depth.

How did you manage the lava?

The lava was all generated as flowline fluid particle simulations. There was a base layer of ‘all over’ emission from an emission map based on the largest cracks on Kronos’s surface. This was then augmented with extra simulations to create specific streams and flicks as the shots required. These were typically of the order of 10 million particles or so for each simulation. The particles were then rendered as blobbies in prman, using a time-dependent blackbody emission shader to get the correct colours as the lava cooled.

Can you tell us more about the use of Kali for the destruction made by Kronos?

Kali is our FEM destruction toolkit. It allows us to take any asset and shatter it at render time. It’s great for this kind of effect as it gives you a really nice recursive cracking effect – big chunks break into smaller chunks, and again into even smaller pieces. When you’re shattering or collapsing something it gives you a very natural breakup. Unfortunately when you’re breaking up something as big as a whole mountain it quickly generates an insane amount of geometry, so we augmented the base Kali sim by turning some pieces into groups of particles that tracked with their parent chunks then broke up into dust, as well as adding extra trailing particles coming from the chunks, fluid dust simulations and particle simulations with specifically modeled rock geometry. Then in composite we added even more layers of dust elements of top.

Have you developed specific tools for this show?

The main new tool we developed was the volume tools for handling huge numbers of large caches in Maya. As well as loading the Field3D volume caches on-demand it incorporates a GPU raymarcher so FX and Lighting artists can quickly preview changes to the shading of the volumes with basic lighting. The tool is scriptable as well in python so artists can combine and remap densities post-sim, as well as perform more advanced operations like displacement and advection, all in a programmable framework. It’s very cool.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

Kronos and all of the enormous amount of destruction that comes with him. Achieved through a good core of FX TDs led by Michele Stocco and Kevin Mah. A great element shoot and some strong compositors led by Jonathan Knight and Richard Little.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

Everything with Kronos and all of the enormous amount of destruction that comes with him.

What do you keep from this experience?

We all learned a lot by being fortunate enough to work on two of a franchise. Our approach from the shooting methodology, the liberal use of large scale aerial photography and always trying to obey the confines of what the real world film making environment allows, was all driven by our experiences on the first film. Then pushing that in small ways.

How long have you worked on this film?

I was on it for about 15 months.

How many shots have you done?

We completed about 280 but worked on close to 350.

What was the size of your team?

Between our offices in London and Bangalore we were around 200 artists.

What is your next project?

I am on Gore Verbinskis THE LONE RANGER. We are all pretty excited. Its a great chance to work with such a celebrated director that uses the VFX medium so well.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

There’s a lot! But here’s a few:

THE GODFATHER I and II, near to perfect.

EXCALIBUR. It burned into my childhood visual memories quite deeply.

DAYS OF HEAVEN was beautifully shot by Nestor Almendros.

Most everything That Chris Doyle has shot for Wong Kar Wai. He’s a great modern cinematographer.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– MPC: Dedicated page about WRATH OF THE TITANS on MPC website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2012