Takashi Yamazaki started his career in 1986 at Shirogumi as a model artist, then it will work as a VFX designer before becoming director. It will directs movies like JUVENILE, RETURNER or DEMON WARRIOR 3. He is the VFX supervisor for most of his films.

What is your background?

I have been strongly interested in Monster films since childhood, especially, backstage work had drawn my attention, and I had kept thinking how I wish I could make Monster movies when I am older. When I was in a junior high school, I watched two revolutionary films, STAR WARS and CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, and my inclinations toward SFX films got stronger. I may add that there are so many people who have been influenced by these two fantastic movies, and I think that many people who are involved in VFX and CG are close to my age.

A few years later, I watched the making of STAR WARS EPISODE V: THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK on television and made up my mind to have a job like this, so I started to widen my knowledge and to improve my skills by obtaining technical books.

In 1986, I entered Shirogumi, a Japanese VFX production company, as a miniature maker. Even though I had worked as a VFX designer on many Films, Commercials, and Event footages, I realized that there was almost no opportunity in Japan to find a VFX job that I wanted to do when I was younger. Then, I decided to create new demand by myself.

I wrote a script with a lot of aliens, spaceships, robots, and time traveling, which is called JUVENILE. This script caught the attention of Japanese production company, Robot, and I made my debut as a film director. After some films, I won several prizes with ALWAYS: SUNSET ON THIRD STREET.

Can you tell us your approach on this space opera movie?

At first, screen writer Shimako Sato participated in this project. I have worked with her so many times, I told her that I would like to help this film in any position because of I was a big fan of the original animation of SPACE BATTLESHIP YAMATO. It will be my pleasure if they use my ideas in any scene.

One day, I got a call that the production crew was looking for a director and they offered me through my experiences of film JUVENILE, RETURNER and DEMON WARRIOR 3.

To be honest, I hesitated to take this position as a director because I was not ready to direct such a dream project, however, I realized that it was a chance to make my childhood dream come true, so I undertook the position with honor.

How did you create the shot that start from the eye of Yuki Mori and stops in a middle of a huge space battle?

Shot of Yuki Mori’s eye was shoot by macro lens with DSLR Canon 5D Mark II. This scene starts from close-up of her face to full body, I took a track-back shot by crane camera with a six axes motion ride with actor. Six axes ride makes reality in shot. We switched CGI actors and aircrafts when the crane stops in the final position.

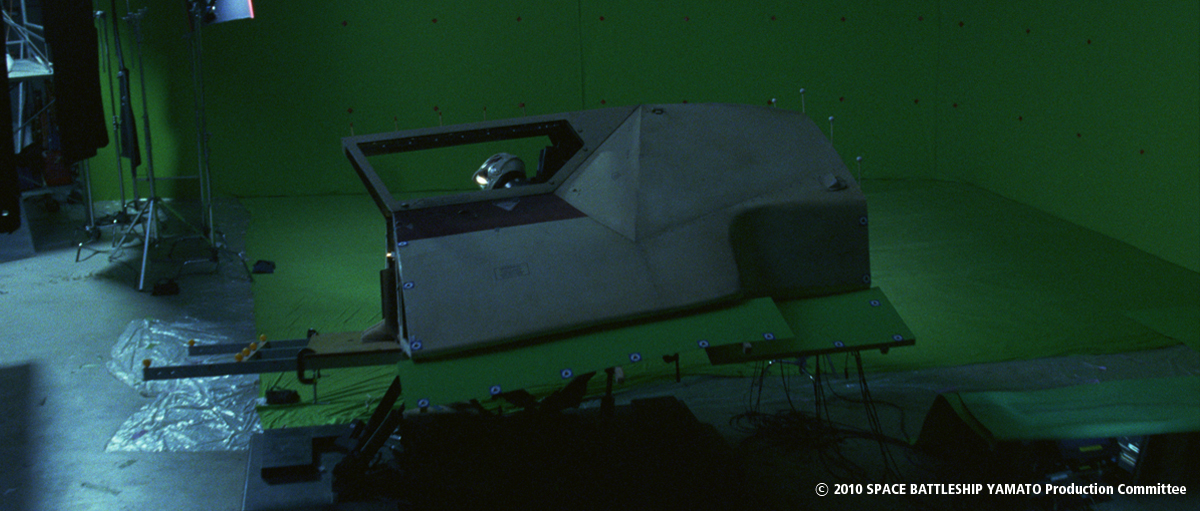

How did you filmed the shots showing pilots in their cockpit?

We shot actors on a six axes motion ride set. Motion ride is a part of the set, we created full body by CGI. It was difficult to composite glass on cockpit by complex reflections, we shot with cockpit frames and replaced by CGI.

|

|

Did you create previz for the choreography of the space battle?

Pre-Visualization (previz) was a important for such as VFX film.

For actors, I let them imagine the background of the scene. Previz helps them recognize around the shot.

For a stage team, They need to design the stage size of the scene, miniature team also design and create props from camera position in previz.

For me, I need to find a rhythm and tempo for editing film.

For editing, editor needed previz to fill for un-finished VFX shot.

Therefore, I started to work on previz a few month before shooting, and the CG team also created previz for own VFX scenes.

|

|

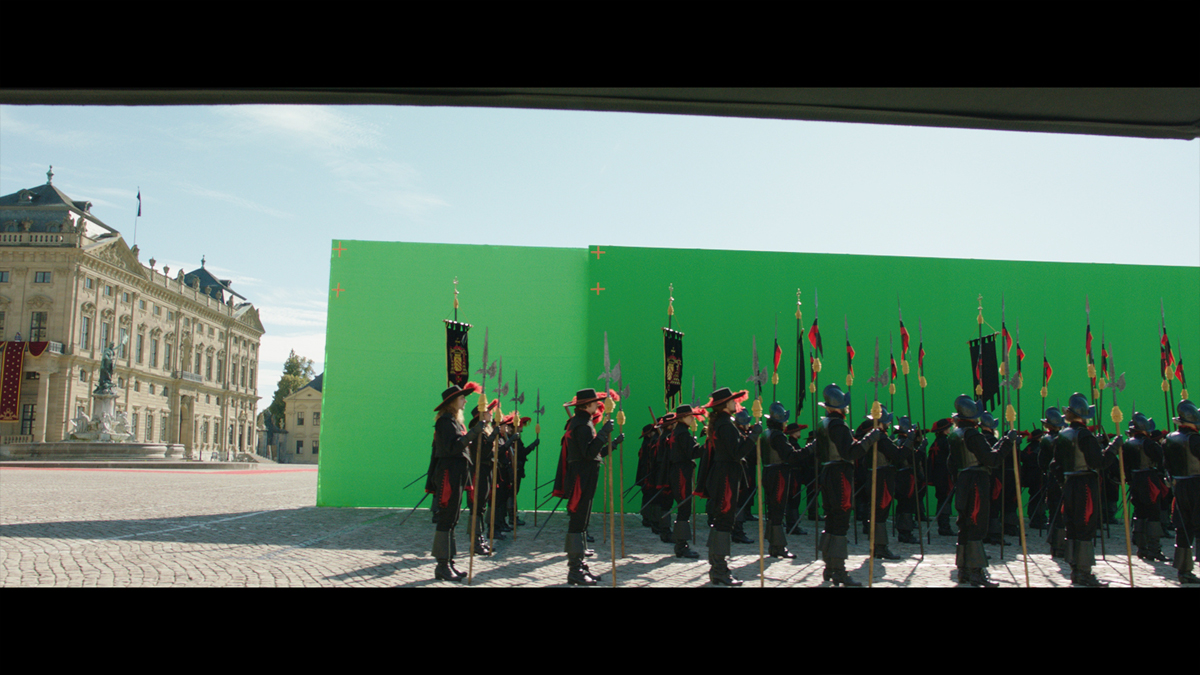

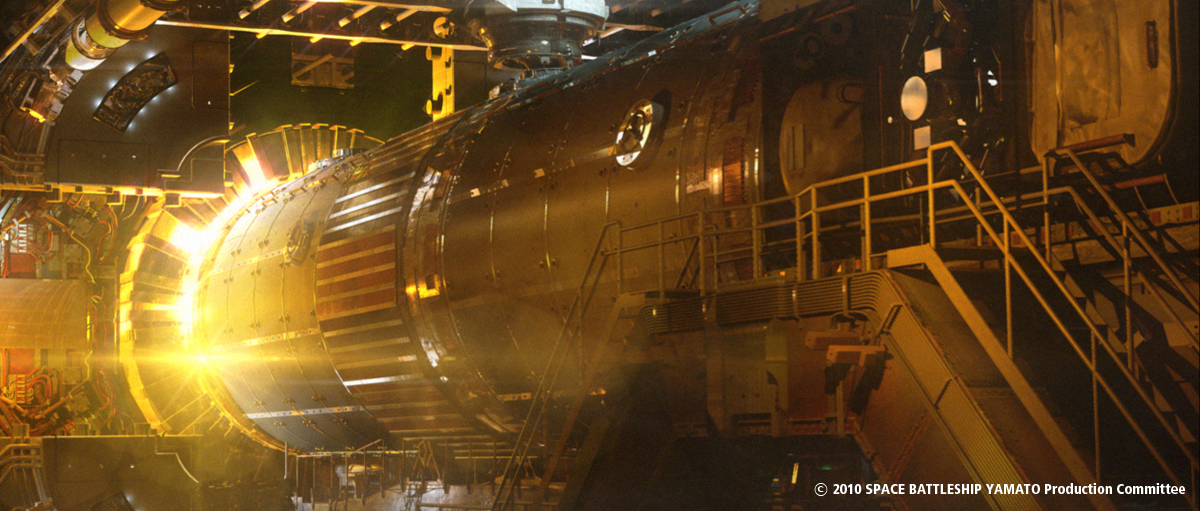

Can you tell us more about the creation of the huge set extension? How did you create them?

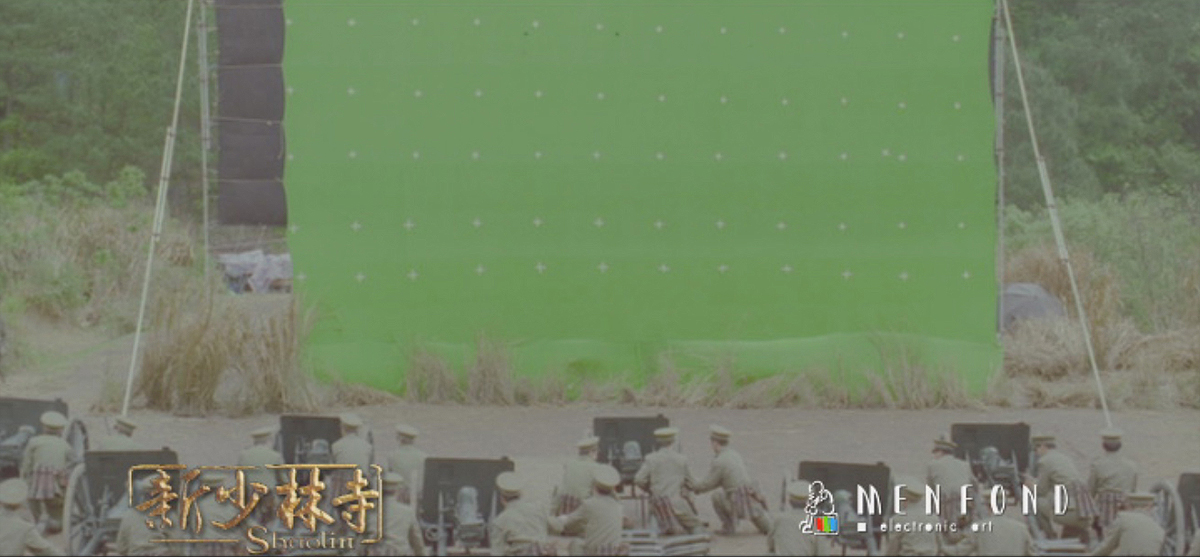

It was created by an ordinary way. The camera tracked the minimum sets in front of a green screen backdrop with 2d3 Boujou match move software and we composited with the CGI set.

But there is a problem on the stage size. The actor couldn’t go through left side in the frame. We switched him with digital actor when passing the another actor on the middle.

|

|

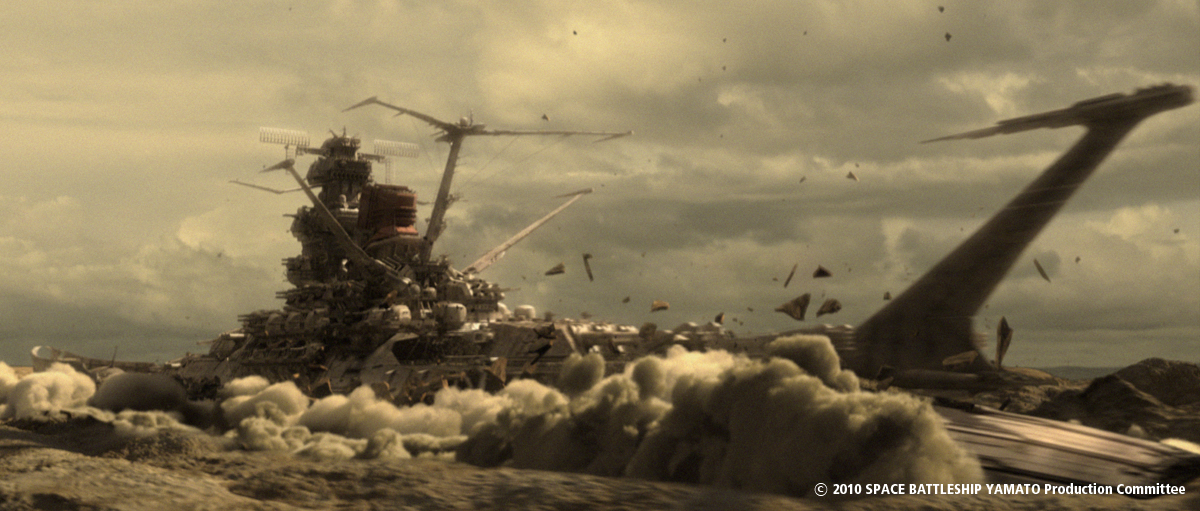

How did you create the impressive shot in which the Yamato is going out the ground?

This scene is the prominent to describe film of SPACE BATTLESHIP YAMATO, I thought this is a very special. However, It was very hard task to for my team who did not have enough effect skills for braking huge objects, smokes. We started with a research for software for braking objects.

After the research, we decided to use RayFire plug-in. but RayFire plug-in is made for 3ds Max and our team was using Maya. We start to learn basic operation from 3ds Max team’s. We were able to use RayFire on 3ds Max exporting FBX from Maya. Finally, we could finish this sequence by the deadline. So, we used 3ds Max as an expensive plug-in for effects.

|

|

Can you explain to us the creation of the shockwave and explosion that destroy the enemy armada?

For the explosion of Gamilas carrier, I told my broad intention to Kei Yoneoka, the CG artist whoes specialty is in visual effect. The details of the intention was; « The Engine of Gamilas forms micro-black hole if it gets damaged. At the moment, everything around it is drawn into, but when it goes to the critical point, the engine of Gamilas triggers a large explosion. »

I left everything else to Yoneoka after I expressed the ideal implosion and the timing of release by using onomatopoeia effectively. For more specific information, please go to his website.

SPACE BATTLESHIP YAMATO mother ship destruction makingA from Kei Yoneoka on Vimeo.

Kei Yoneoka: “This shot can be divided mainly mother ship destruction by black hole and huge explosion. Most of them are made with 3dsMAX. I put keyframe animation on the sphere object to control of the timing that black hole begins to occur and speed of rotation. Then I used FumeFX’s velocity information which emit from sphere object to make particle an organic motion. After that I rendered those tens of millions particles by using Krakatoa. When I made a center core of black hole, I used Realflow with computing vorticity then I extracted that information and rendered by using Krakatoa. The destruction of mother ship was done by Thinking Particles.

The huge explosion after shrinking of the black hole was also put keyframe animation on the sphere object to control of the expanding timing. Then I used FumeFX’s velocity information which comes from sphere object to make particle an organic motion. I put a plant or microorganism’s picture to the tens of millions particles as a texture then rendered with Krakatoa. I sculpted emitter object having bumpy shape with modo in advance in order to make an organic style.”

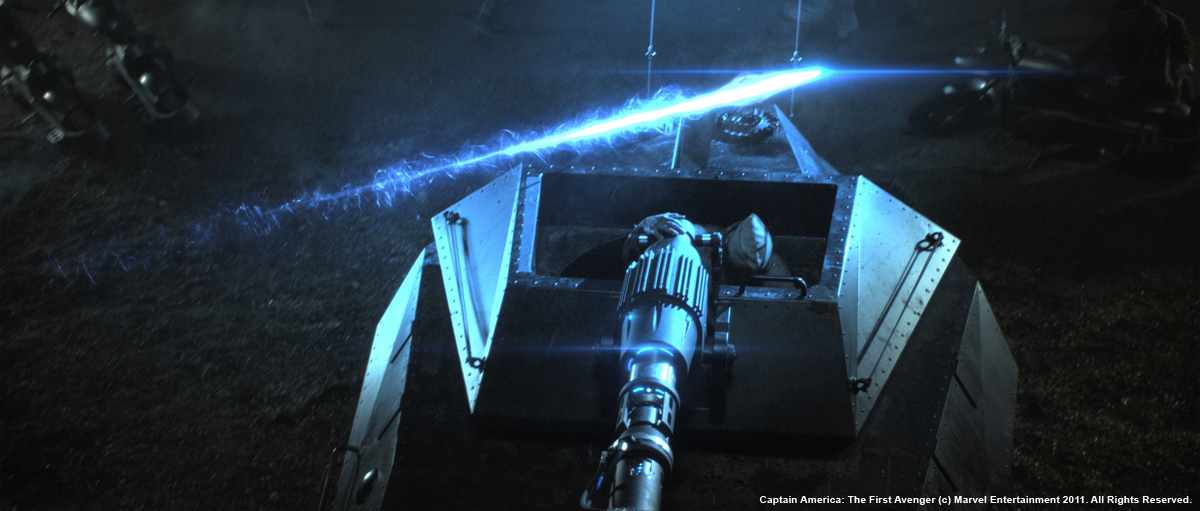

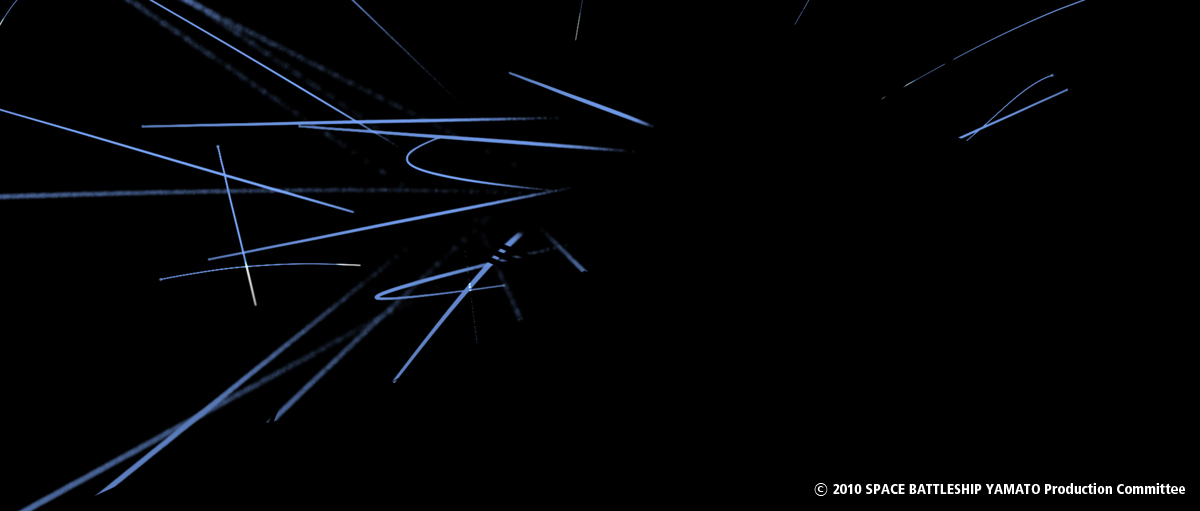

How did you create all those pyro elements such as the missile trails, lasers and explosions?

We mostly used N particle of Maya for the pyro elements. I combined a lot of shooting footage on explosions.

|

|

|

|

What was the real size of the sequence with the heroes on a truck?

It was very tiny studio. There is a only truck in front of green screen. We shot a crane camera to make it looks like following a moving truck. And we covered CGI elements around truck.

|

|

How did you create all the huge environment around them?

We created the strange rocks using Pixologic Zbrush. We also put matte paintings and photos of miniature for background.

Through the scene, Actors performed arriving in the enemy’s territory and fight with Gamilas fighters, and arrived to innermost place and escape from there. But we shot only truck and some rocks on green screen, we had to create hole backgrounds digitally.

This whole scene was quite difficult challenge for us to create many kinds of backgrounds, but we are confident that the audiences did not realize how little the actual stage size. This is VFX.

Can you tell us the creation of the particles going off Yuki Mori?

We used Maya nCloth for them. We just processed the particle, but I was particular to blew jacket and helmet by the shock of the particles.

How did you create the beautiful final explosion?

The final explosion was also made by a CG artist, Kei Yoneoka whose speciality is in visual effect.

The concept for this scene was to re-create the sad, but beautiful atmosphere of what one of the original piece FAREWELL TO SPACE BATTLESHIP YAMATO depicts and to make it 2010 version. Yoneoka created mysterious and beautiful explosion, which deserved to cap this film, by incorporating marvelous gaseous nebula-like image in an aftereffect of the blast, which looks like supernovas.

SPACE BATTLESHIP YAMATO Final Explosion making from Kei Yoneoka on Vimeo.

Kei Yoneoka: « In this shot, I also put keyframe animation on the sphere object to control of the expanding timing. Then I used FumeFX’s velocity information which comes from sphere object to make particle an organic motion. For the emitter object of the element like a dark nebula, I used gray scale texture which I modified cloud or white cape pictures to make the particles having a natural distribution. Those tens of millions particles was rendered by Krakatoa.”

Did you create specific tools for this show?

No, we did not invent any tools. I focused on employing what we had efficiently.

What was the biggest challenge on this project?

The biggest challenge was that the Japanese described full-scale cosmic space in a science fiction film. Compared with Hollywood films, the budgets are small (I guess one-tenth or one-twentieth.)

And we did not have enough knowledge. I also never done before there are a lot of challenge.

We have been working hard to remind me that Japanese can produce cosmic space feature film.

I hope this experience helps me with next challenge.

The difference between Hollywood and us is not only the budget.

It will be experience, I believe.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Has there been a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleeping?

We always prepare the knowledge and skills before start project. But this project was started without enough skills to describe such as special effects. It was unprecedented challenge to produce the significant shot of a theatrical released film as learning basic operation of unfamiliar software.

We spent a lot of time for this scene, so I felt really relieved when we finished the shot.

|

|

How long have you worked on this film?

We worked on stage for 3 months and 6 months for the digital work.

What are your softwares and pipeline from Shirogumi?

We used Maya as a main CG software, 3ds Max and RayFire for certain scenes. Nuke for compositing, ZBrush for special modeling, Photoshop for matte paintings and Thinking Particles for explosion effect. We used DPX from DI room of IMAGICA, the post production company.

How many shots have you made and what was the size of your team?

The total number of shots were 436 cut.

There were 34 original staffs, 21 people for support and 12 people for motion capture related work.

What do you keep from this experience?

I realized how difficult it was to produce cosmic space films in Japan.

However, I believe it will refine through this kind of project. So, I would like to keep challenging for the new things.

What is your next project?

One of the next project is called FRIENDS NAKI IN MONONOKE ISLAND.

It is a digital animation film based on an old children’s tale (or a fairy tale), which is created with miniature background and CGI characters technology.

http://www.friends-movie.jp/

The other project is called ALWAYS SUNSET ON THIRD STREET ’64.

This is the third series of ALWAYS. We shot with real 3D camera, so it is a true 3D film It is not 2D to 3D converting film. My idea is taking audiences to the three-dimensional world in 1960’s Tokyo.

http://www.always3.jp/

What are the 4 movies that gave you the passion of cinema?

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND

STAR WARS series

SEVEN SAMURAI

IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Shirogumi: Dedicated page about SPACE BATTLESHIP YAMATO on Shirogumi’s website.

// SPACE BATTLESHIP YAMATO – TRAILER

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2011