Wes Caefer is a self-taught artist. He oversaw several projects at Worldwide FX. THE EXPENDABLES is the second collaboration between Wes and Sylvester Stallone with RAMBO.

What is your background?

My formal training is from the US Military and Emerson college in Boston. But the bulk of my knowledge about visual effects is self taught and learned on the job. This is a slow way to learn some things and I don’t know that it could be done this way anymore. I learned as the digital age was growing so I was able to pick it up as it developed (and I’m sure there are some gaps). I’m sure that it would be best to get a lot of the basics from a school since there is so much to learn.

How was your collaboration with Sylvester Stallone?

THE EXPENDABLES was the second film that I had done with Stallone. I had also supervised RAMBO. I have to say that he can be challenging. But in a good way. I have flown alien fleets, made giant spider and miniature robots and all manner of wild things but Sly would throw something at me that would make me stop and say, Gee. How am I going to do that? All the time remembering that we have to maintain a level of realism that is not required on something like a giant squid movie. People will go along a bit with something that they have never seen before. But this is the sort of thing that everybody knows what it should look like. They have seen airplanes. So if our airplane looks wrong, even slightly, we have failed.

|

|

Can you tell us what WWFX did on this movie?

Easier to say what we did not do. There are well over 1,000 shot in this movie that we did. Not just the ones you would expect like the palace being destroyed which was a mixture of miniature and digital FX). But carloads of things you would not expect. Like fixing continuity issues and removing lighting equipment from the tunnels where it was so tight it wa impossible to light without catching the equipment on camera. We also removed stunt pads that kept our stunt team out of the hospital and added 1,000s of muzzle flashes.

|

|

What did you do on the opening sequence?

The boat at the beginning was built on a stage in 2 pieces. The top half was next to the bottom half so we had to marry those two. And of course the muzzlle flashes, knifes, lasers and some of the thermal vision was real and some of it was us treat regular footage to look like thermal.

The movie includes several models. How did you decide what would be made model or CG ?

CG was the way to go for nearly everything since we did not know what was going to be required it just gave us the flexibility to make the model do whatever we needed. But the palace falling down was a building. That needed to be realistic and Sly and I both agreed that all that tiny detail and randomness that a crumbling building would have is still better done real. Real is always better if possible. Sly said as good as the CG is these days, it still has a kind of « CG » look to it when it comes to this sort of thing.

|

|

What did you do on the car chase?

We added bullet holes as they were formed and there were practical holes in the glass after that. But in editing Sly felt that it was not clear this was bullet proof glass and wanted to see the slugs stuck in the glass so we added the little dark spots to every hole in every window for every shot in the sequence. Some of the holes weren’t there at all and we added them. Muzzle flashes of course and put a human face on the dummy that was in the passenger seat of the first car that crashed. All the interior shots of people reacting and such was bluescreen. And we added glass breaking from the windows in the rear window that gets shot out and the car that gets hit by the truck. I might add that there was not time to shoot plates for the bluescreen that was outside the windows of the cars in the chase. I did not know how I was going to get what I needed because there was no getting around it and there was just no time to get any of these plates. I rented 3 Iconix HD cameras and attached them to the camera car for most of the chase. Then I has something that I could use that actually covered all the same terrain and car movements that the picture car was making. They were small enough that they could not be seen so I did not even have to remove them in post.

|

|

About the matte-paintings on the island. How did create them and what was your references?

The island was built from footage we shot in Brazil. We did manipulate these a lot as Sly really wanted fewer building and poorer looking dwellings. We also had to remove or change any signs that we could read as the island Sly invented speaks Spanish.

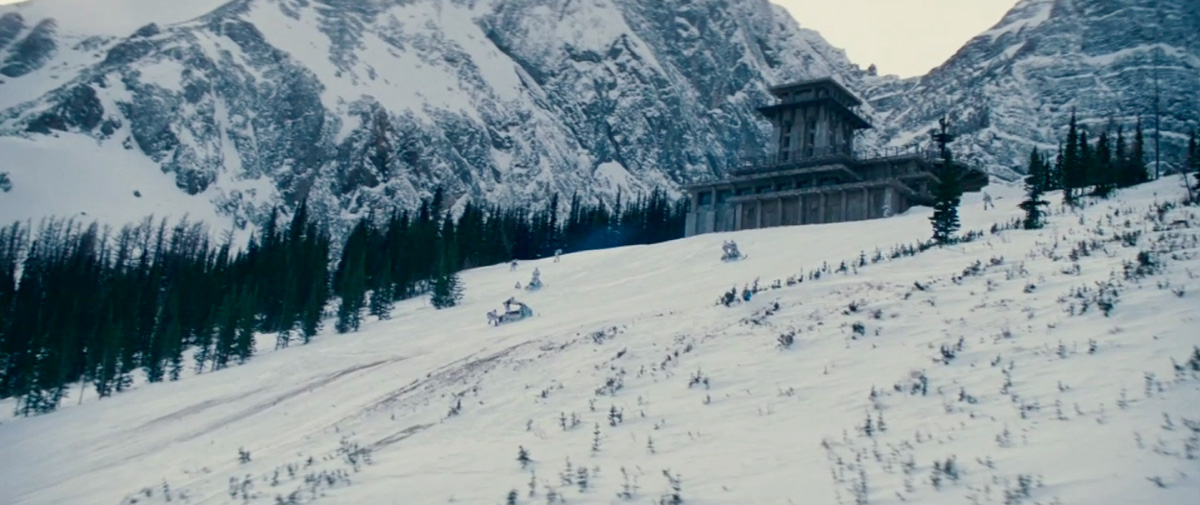

|

|

Did you created a model version of the plane or a CG one?

There was a real plane and a CG one.

Are you involved on the shots in which Jason Statham is on the front nose of the plane?

They actually got Jason to be in the front of the plane. But we are still involved. There was a rubber band keeping his glasses on that we erased. The plane never had guns on it (partly because this was a kind of last minute idea that Sly had) so we added them later. And Sly wanted this place to be much less populated and poor so we removed boats from the water and houses (also our production trucks) from all the terrain they are flying over. We also shot some stuff of him in front of bluescreen but I think there is only one cut used in the final cut. Most of it he is really in the nose of that plane.

|

|

Can you explain us what you did on the final sequence? What have you increased in this sequence?

In that final sequence, we brought the palace down as I explained elsewhere. But the palace was not there at all. There was a real building in Brazil that we got a few shots in front of (that needed extensions as it was not as big as the one Sly wanted). Then the rest was shot in New Orleans. So every shot in the end that show the palace or anything outside the fence we had to put it there and every explosion and muzzle flash needed to be put in or enhanced. The bullet hits are all us and every knife that gets thrown is us. We put the blades on the helicopter and removed the stunt pads. We added blood and wounds and bullet holes in bricks and trucks. We moved explosions from where the really happened to where Sly wanted them and we changed the speed of a great many things. There really isn’t much in the last reel that we did not tocuh in one way or another. Even that goodbye at the plane was us. They shot that on a stage just the doorway part of the plane then we added the CG tail of the plane and the plate of the dock behind.

|

|

How did you create the flames on Steve Austin?

The flames were all done in Maya but we had to match move animate a Steve Austin shaped particle generator. There were also layers of lighting effects and color correction. This was one of the toughest sequences in the whole film.

|

|

How did you distribute the work between the two branches of WWFX (One is in Louisiana and the other one in Bulgaria)?

We had just opened the facility in Louisiana. So I tried to send them the less challenging stuff to give them a chance to get up to speed and settle in like all the bluescreen work in the car and airplane windows. By the end they were doing some of the very complicated work too and that was assigned to them because the Bulgaria crew already had a full workload and the guys in Louisiana were up to anything by that point.

What was the approach of Sylvester Stallone about the visual effects?

Stallone’s approach to visual effects goes like this. « Wes. Come here. » And before you say anything, the answer is, « Yes. »

What are your softwares?

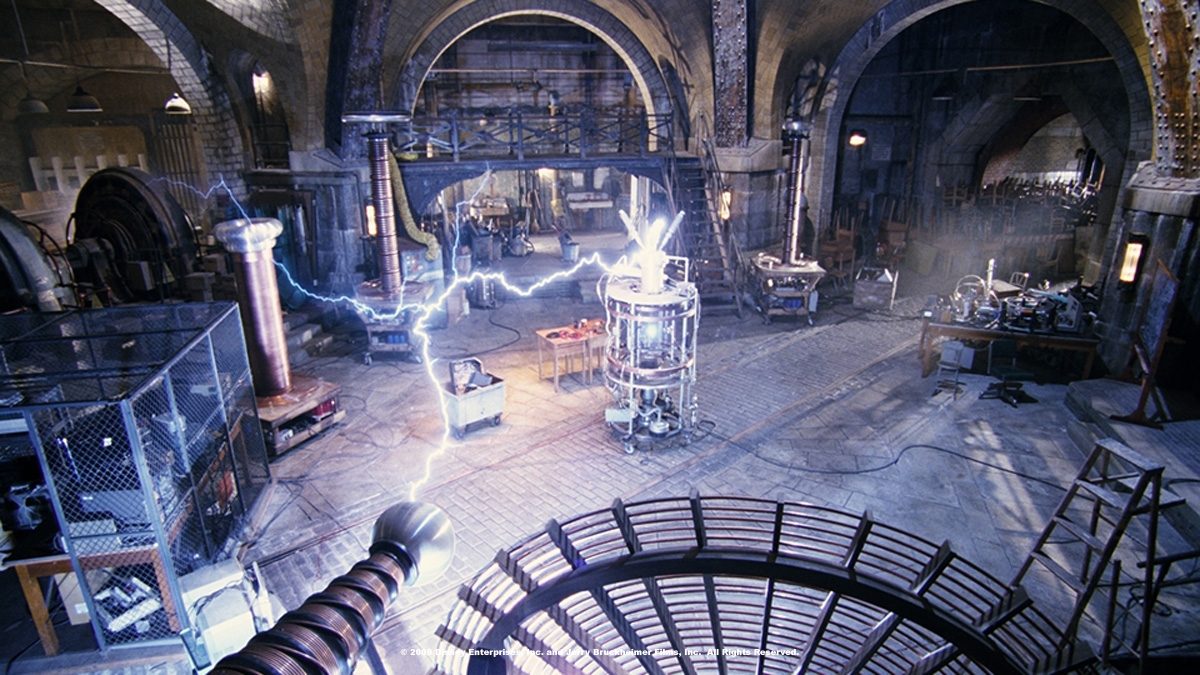

We use Digital fusion mostly for the compositing and Lightwave and Maya for the 3D elements and animation. All the particle work was done with Maya.

How many shots have you done and what was the size of your team?

WWFX has around 200 people in Bulgaria and another 60 in Shreveport Louisiana. I had everybody working on this for part of the time and most of them for most of the time. There were over 1,100 shots in the final cut but that is misleading. We finished a couple hundred more and worked on more than that. We could not wait for a final edit before we started work and the edit changed daily. Sometimes to include more of our work because once he saw how it looked, Sly thought it was cool and wanted more. And some things that we had finished were no longer in the film because Sly had taken another take of the same scene for performance reasons or it was just out of the film all together.

Is there a shot that prevented you from sleeping?

It was the stuff that was unplanned that prevented me from sleeping. The fight with Steve Austin for example was supposed to be just a stuntman lit on fire for real. Once we got into editing, they felt that the sequence was not as dynamic as the character deserved. But some of the action that was shot during the fight before he was on fire could make it better. But he was not on fire. I knew this would be time consuming to get it right and the decision to do it this way came very late.

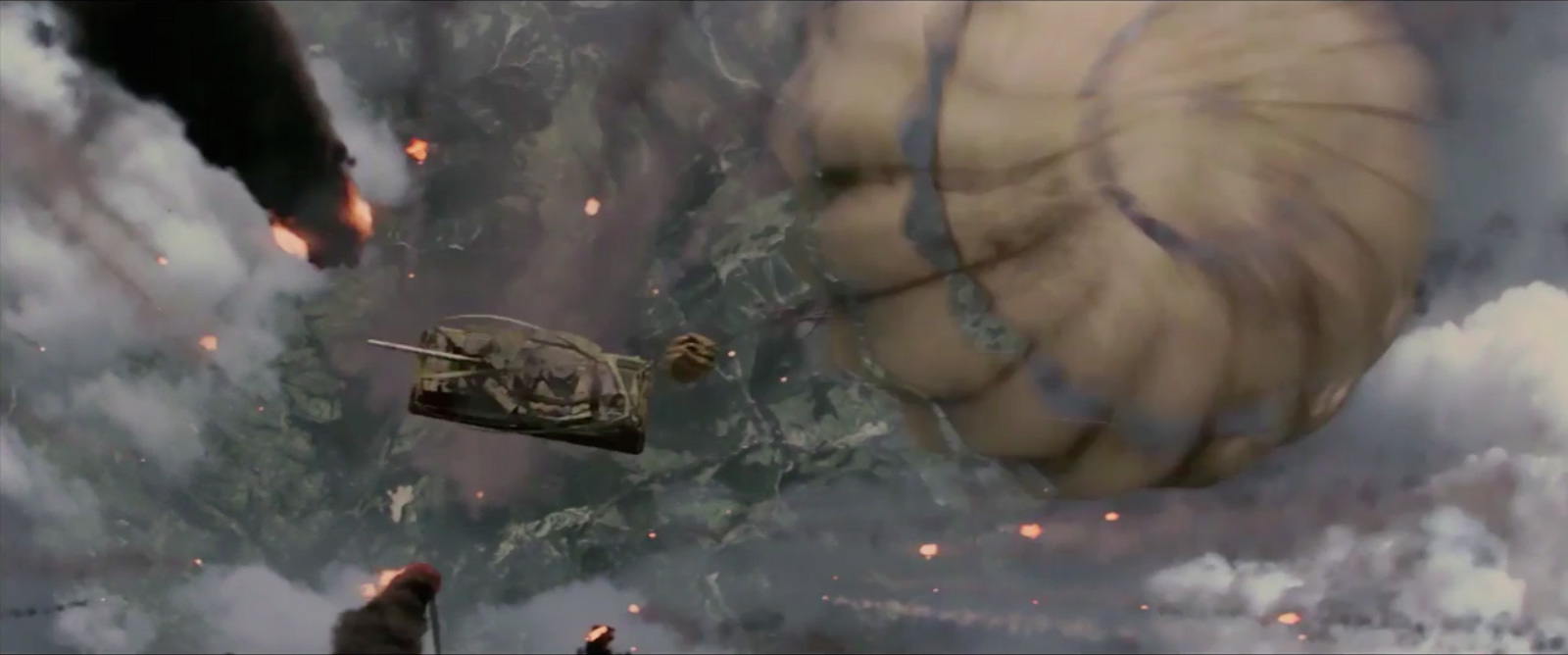

Also the palace coming down was not exactly according to plan. We had planned to do it as a miniature. That seemed the best and easiest way to get the level of realism that we all wanted (especially Sly). But Sly had a number of clips of controlled demolition of hotels in Las Vegas being imploded and stuff like that. So we talked about it and it was clear that he wanted the building crumbling in on itself and that there were small flashes followed by crumbling in section in a specific order with lots and lots of dust clouds almost like 9/11 footage. So I got Fantasy II and Gene Warren Jr. to build and shoot that miniature and we got Joe Viscosil to blow it up. It was going to be fairly clean as I knew that Maya could do the dust clouds just fine and I wanted Sly to be able to determine what could be seen and what was obscured. We cut it is and he lives with it for a while. Then he turns to me and says, « It needs fire. » Now I have something that makes me lose some sleep. Literally. The bulk of this work was being done in Bulgaria and I was in the editing room in L.A. So I am up all night working with the artists that are 11 hours ahead of us and getting continuing to work a full day in L.A. getting the feedback on what we had done during the night.

|

|

What did you keep from this movie?

I learned a great deal of course. One useful thing I can tell you is that because of the nature of VFX work, no matter what they ask, you can do it. That is what we do. But you should not say ‘Yes.’ Directors and producers stop listening after they hear ‘Yes.’ So if the answer is, ‘Yes, but that will take a team of 5 about month and a half.’ They have stopped listening after ‘Yes’ and did not hear about how much of your resources would be eaten up by this. I now instead answer something like, ‘That would take a team of 5 people about a month and a half. But yes. We can do that. Then they actually think about how badly they need it and if they go ahead, are not surprised at how long it is taking.

What is your next project?

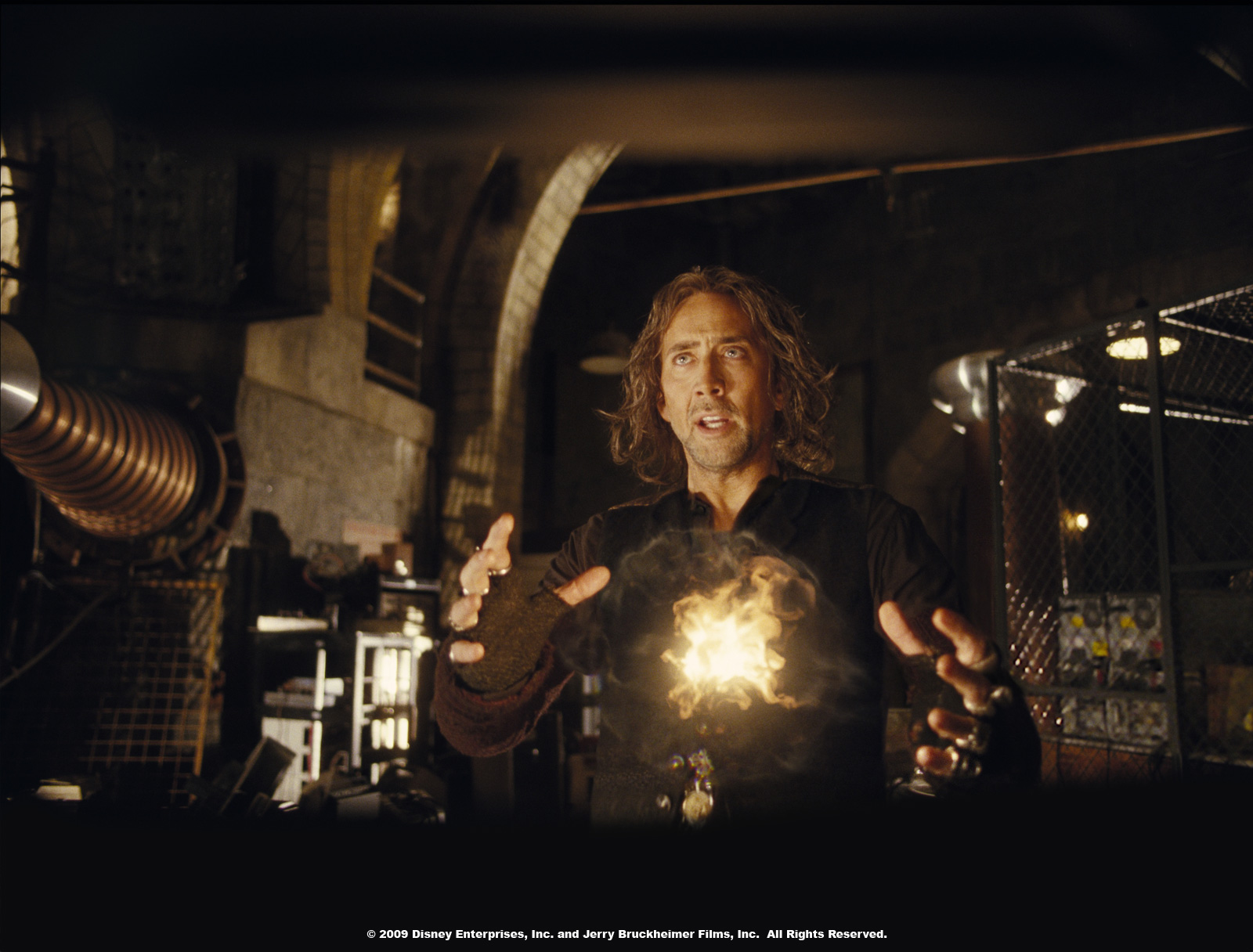

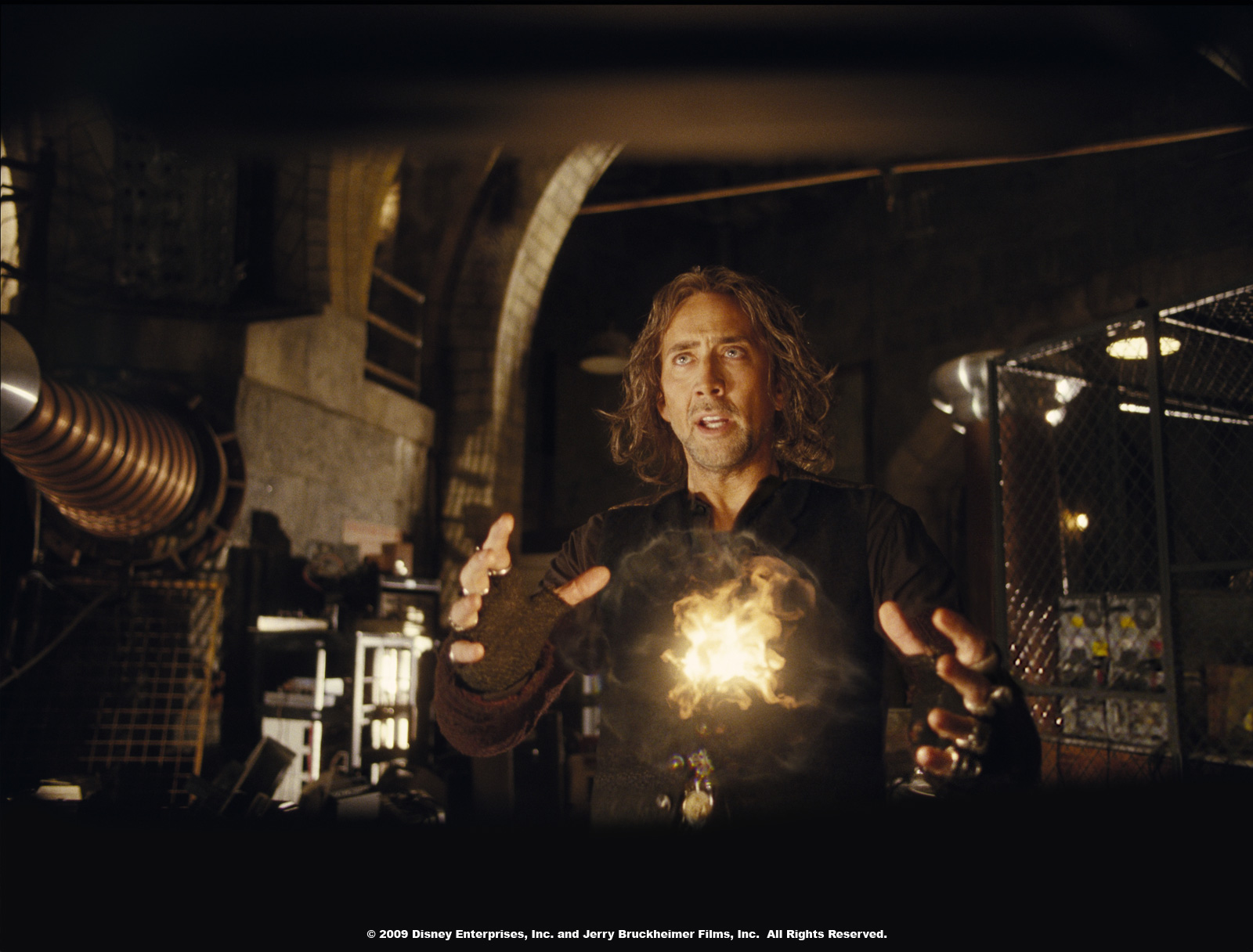

I am right now supervising the VFX for TRESPASS. Joel Schumacher is directing and it stars Nicholas Cage and Nicole Kidman.

What are the 4 movies that gave you the passion of cinema?

I have loved « monster movies » since as far back as I can remember. I caught 20 MILLION MILES TO EARTH when I was very young and solidified and already established need to work in film. Then KING KONG (1933 of course). FRANKENSTEIN and 7TH VOYAGE OF SINBAD.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Worldwide FX: Official website of Worldwide FX.

– fxguide: Article about THE EXPENDABLES on fxguide.

// THE EXPENDABLES – WORLDWIDE FX – VFX BREAKDOWN

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2010