Back in 2018, Will Reichelt explained in detail Animal Logic‘s work on Peter Rabbit. He’s back today to tell us about the film’s sequel.

Simon Pickard has been working in visual effects for over 20 years. He has worked on many films such as Happy Feet, The Golden Compass, The Lego Batman Movie and Peter Rabbit.

What was your feeling to be back in the Peter Rabbit universe?

It was an absolute pleasure to return to Peter Rabbit. In a way, it felt like we never left – the Director, Will Gluck had started writing the script not too long after the release of the first movie so it felt like we’d finished, had a few months off, then rolled our sleeves up almost straight away again on the new one. I was excited to go back as well because it was such a fun, crazy ride the first time, and one of the best experiences of my professional career.

How was this new collaboration with Director Will Gluck?

Will Gluck is a brilliant writer, a sardonic wit, a collaborator open to ideas from all corners and an absolute perfectionist who never stops looking for ways to make his movie funnier and more. There were definitely moments on the first movie where we were panicking about finishing on time because he just would not stop changing things right up until the final nail-biting second before everything had to be delivered. Having gone through it once though I was prepared this time, and I knew that the final product would be something special that everyone working on it would be proud of.

The other great thing about working with him again was that since we’d figured out the production basics on the first movie and had developed solid processes from shooting through to final shot production that Will Gluck was comfortable with, which meant we were able to handle the increased complexity of the second movie.

Did Director Will Gluck asked you for major changes since the previous movie?

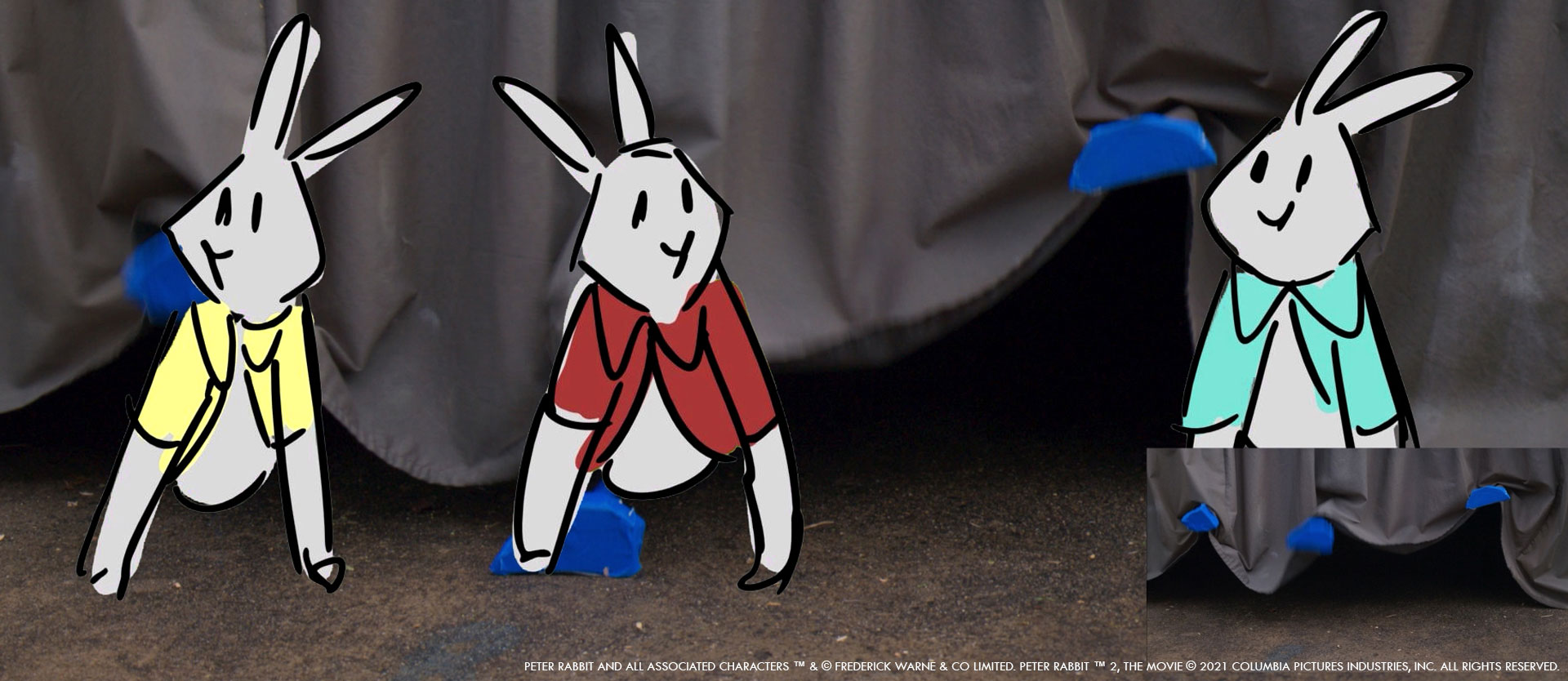

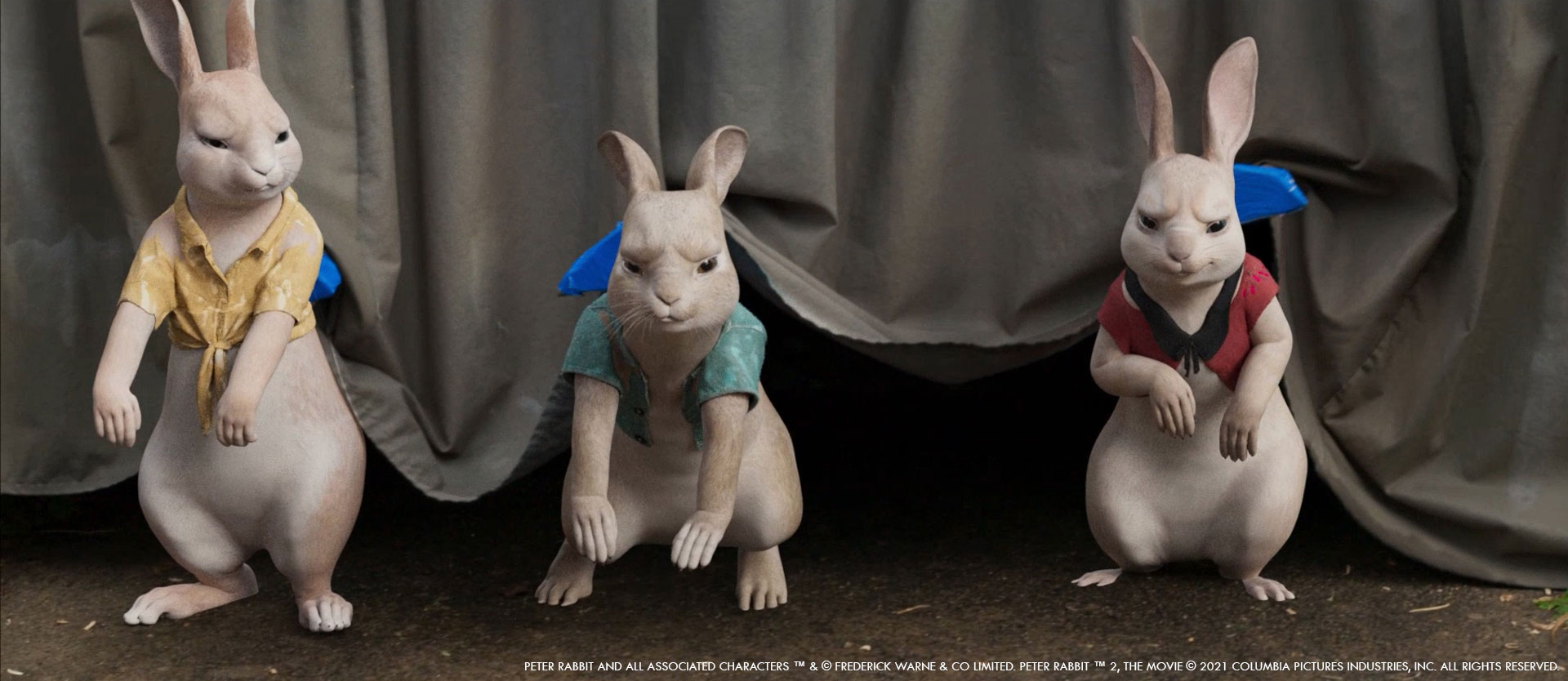

There weren’t really any major changes to what we were doing with the characters, but we did discuss the fidelity of the performances and how we could get more nuanced with the facial animation in particular. On the first movie, a lot of the framing of the characters was wider, showing more of the character’s upper torsos or full bodies, but the intention on this one was to be do more closeups on their faces which meant that their expressions could be more subtle and complex.

Did you change your approach on the sequel with your VFX Producer and your team?

The setup was a bit different on this movie compared to the first one in terms of the production structure, this time I was working externally for Sony as the overall VFX Supervisor alongside VFX Producer Fiona Chilton, but the core creative team were nearly all Peter Rabbit veterans – Simon Pickard (Animation Director), Kelly Baigent (Head of Story/Second Unit Director), and Matt Middleton (Animal Logic VFX Supervisor) all worked on the first movie, and this time we were working with editor Matt Villa.

How did you organize the work between the Animal Logic offices?

All of Animal Logic’s animation work was completed at the Sydney studio.

How was split the work between Animal Logic and Method Studios?

VFX Supervisor Matt Middleton, Animation Director Simon Pickard and the team at Animal Logic handled the main cast of characters and associated interactions, as well as the Lake District set extensions around the McGregor Manor and the extensions outside Nigel Basil-Jones’ London office.

Method Studios in Melbourne led by VFX Supervisor Josh Simmonds and Animation Supervisor Nick Tripodi brought the character of JW Rooster II to life, handled set extensions for the McGregor toy store, the Farmer’s Market, and some of the car chase scene set extensions that were shot at Carriageworks in Sydney, as well as the McGregor digital double work.

How did you enhanced the various CG models and especially Peter Rabbit and his family?

On a base visual level, most of the original characters were represented pretty much as they were in the first movie apart from Peter, who had a small groom design update on his face, and Felix D’eer who got some brand-new antlers.

Can you elaborates about the fur and groom work?

The rabbit fur is modelled on a real rabbit with three distinct layers – a base level of soft down, the main layer of guard hairs and the sparser but longer guide hairs. It was important for us to approach the visual fidelity of the characters as if we were creating a match to a real animal so that the anthropomorphic performances of them had a grounding in reality.

Can you tell us more about the eyes work?

One of the things that we were determined not to do with our characters was to give them overly bright cartoon eyes, it’s one of the things that helps to ground them in the real world. We spent a lot of time in Lighting, Comp and then in DI balancing them and making them consistent so that they felt appropriately dark but still with a little sparkle and detail in the reflections to bring them to life.

How did you handle the lighting challenges?

Compared to the first movie, the sequel had more complex environments to integrate our CG characters into. Along with the standard day exterior and overcast weather, we also had some fun interiors like Nigel’s office with its overhead fluorescent light and window daylight combo, Barnabas’s dark basement hideout with overhead tungsten lamps, and even the dark ambient interiors of a recycle bin and post box!

Generally, the lighting was approached with intention of integrating the characters as seamlessly as possible into their environments, then adding subtle shaping and beauty lighting to bring out their faces and expressions.

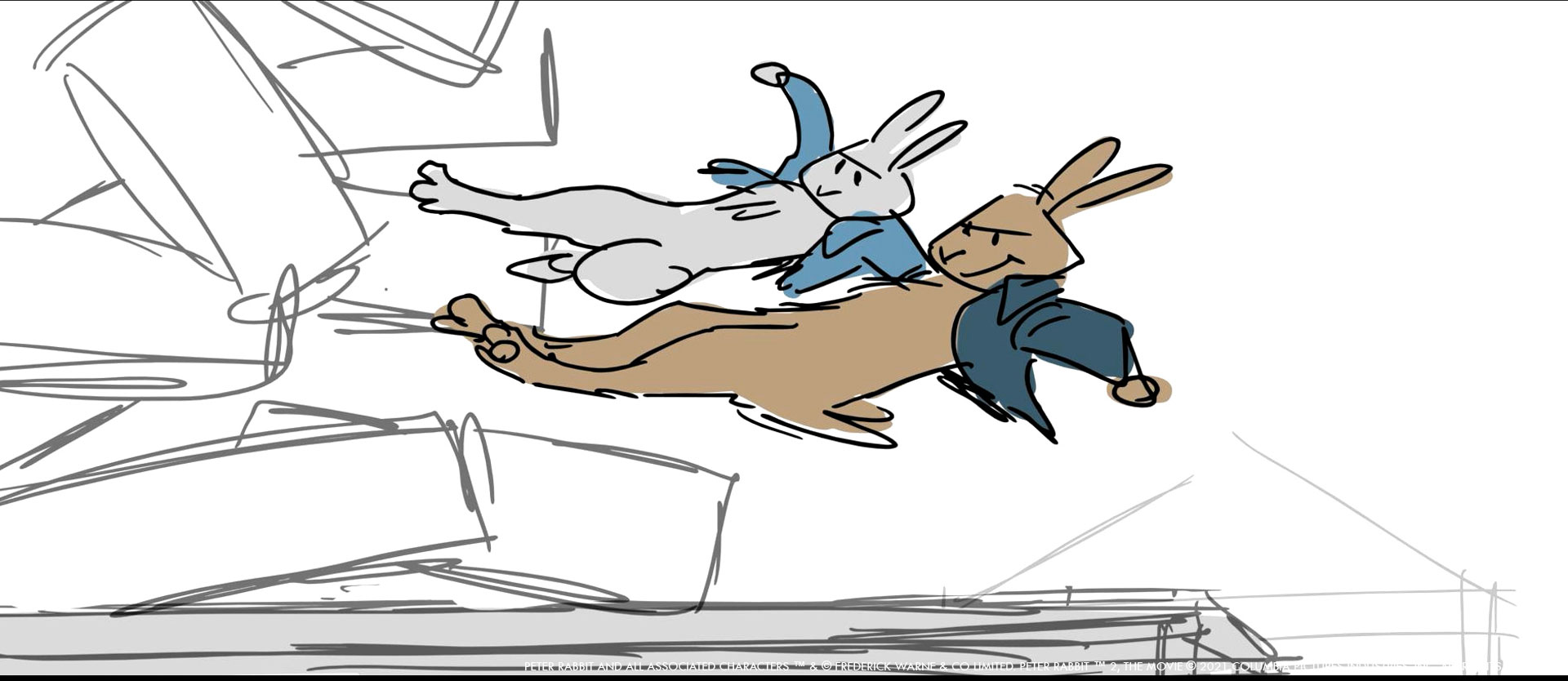

Can you explain in detail about the animations work?

Once the storyboards from the Story Team, headed up by Kelly Baigent, were approved and then taken through Rough Layout for the cameras and staging, we’d start layering in the animation. We’d discuss what we were thinking, and mock-up ideas for each shot. We’d look into reference material and mix in the voice actors performances to get a “blocking pass”. It’s different with every Director but the aim of a blocking pass is to try and get something playing strongly enough so the ideas are clear before working up the shot. As Will Gluck had been through the first film, this ‘language’ was already established and he knew when to trust us to flesh out the shot and when to keep working something so the comic timing completely landed.

The voices casting is really impressive. How did you use their voices performances for their characters?

Simon Pickard // I always ask for the voice recording sessions to be videoed and sent to us and we were lucky on both films that Sony shared hours of this footage. Actors like James are so expressive in their sessions and as animators we can draw from the gestures and acting cues they hit. Quite often we’ll also use parts from different takes mixed with others to create the ‘spirit’ of the overall performance. We combine this with our own acting references, which we do on most shows, to create a solid blueprint before we ever start the shot.

Which shot or sequence was the most complicate to animate and why?

The complexity on the 2nd film was challenging from start to finish with a lot more interaction shots between the CG characters and live action actors. The Heist sequence took this interaction to the next level where the animals were fighting the farmers in very physical complex ways. Most shots also had a high character count which gets tricky for the animators as the animation software runs slower and slower. The scene took a lot of work and patience to get right.

How did you manage the challenge between realistic and cartoon animations?

The challenge ultimately is that as you blend in and out of both worlds as an audience you should never feel it. It should be totally natural as a viewer for a highly realistic rabbit to hop across the screen, stand up, and start talking. What we found on the first film is that once you’ve established these rules the viewer goes along for the ride. We were careful to introduce these in a layered way though, so bit by bit you’re adding to the rules of the world. Once the rules are established, you can play around a bit to surprise the audience, for example when the rabbits suddenly break out into a song and dance number. We also lean heavily on reference from real animals even in the acting shots. As humans we naturally imprint human characteristics onto our fury friends, for example, when we’re trying to sell confusion on the rabbit, adding a head tilt that a pet dog might do, is something pre-established and understood by the audience.

How does the super slow-motion shots affect your work and especially for the animation and FX?

When we animate in slow-motion we always pay close attention to how the shot plays at real-time, so it’s grounded in reality. You can push the shot of course but if it feels fake when you ramp it back to real-time there’s a good chance it’ll feel slightly off in slow mo.

Domhnall Gleeson has many cartoon stunts. Can you elaborates about them?

Given how popular the physical comedy from McGregor was in the first movie, Will Gluck wanted to double down on this one and take it to another level. Will’s a big fan of shooting as much as possible in-camera, and Domhnall has a lot of enthusiasm and is up for almost anything, so the gags were always approached with the mindset of what and/or how we could shoot something to use as a base, with VFX there to support and enhance.

For the scene at the wedding where McGregor is hoisted up into the air by balloons, we hung Domhnall upside down on a huge crane and lifted him up about 100 feet into the air, then painted out the crane and safety rig and added CG balloons for the final shot.

The shot where he is kicked across the garden into the hedge was a complicated blend of an initial mimed impact performance from Domhnall, a quick blend into his stunt double being thrown backwards on a wire rig, then a second blend back into another performance by Domhnall at the end of the shot where he’s recovering on the ground. The blends required a CG face replacement on the stunt performer and some tricky comp work to get it to all mesh together.

For the slow-motion shot where Peter kicks McGregor in the face, it was particularly important to get the interaction looking right as the shot was filmed on a Phantom Flex at 1000 frames a second with nowhere to hide. Domhnall wore a blue glove and slapped himself as hard as he could in the face with a small blue piece of rubber. We then shot a clean pass of him miming a reaction to get the other half of his body and comped the two halves together and integrated in Peter. A fun detail to watch out for in that shot is the mouthful of egg white “spittle” flying out of Domhnall’s mouth, which took a number of takes to get right.

When Domhnall rolls down the hill, it’s really him for most of that sequence, apart from one or two shots with his stunt double when he’s really flying, and then a shot at the end with a digital double that takes it intentionally into cartoon territory.

Kids absolutely love these gags – from every screening I’ve been to, they consistently get the biggest laugh of the whole movie.

How did you work with the SFX and stunts teams for the creatures interactions?

The planning for each beat or action always involved a conversation about how we could shoot something practically, and it was usually done with Art Directors Sophie Nash and Nick Dare, SFX Supervisor Dan Oliver and Stunt Coordinator Glenn Suter. Glenn would shoot and edit his own stunt-viz and include me in the early stages so we could figure out where the split between practical and CG would be. Dan and his team came up with all kinds of inventive gadgets and techniques to achieve practical effects, from simple things like using hidden fishing line to pull objects, through to more complex setups like the puppet wine bottle Peter uses to squirt practical “champagne” over the kids’ mother, or the cheese-pushing machine that simulated the effect of Peter and Barnabas fly-kicking the stack of cheese down on to poor little William Pemberley at the Farmer’s Market. Sophie and Nick helped design props that would work for our purposes, like the rabbit cages – when the rabbits were inside the cages, they needed to be quickly adjustable frameworks with a removable mesh so that we could add it back in later as a CG element.

One of the shots that felt like a perfect synergy of input from all of us was the gag towards the end of the film in the chase where the Aston Martin smashes through the toilet block. Sophie and Nick designed the block, Dan built and rigged it to smash, and Glenn drove through it in a stunt vehicle to generate the impact. Keeping the setup intact, we cleaned up the debris and shot a second pass of Rose Byrne and Domhnall Gleeson driving through the same path and same lighting in the Aston Martin, which we comped together with some screaming CG animals in the back!

Can you elaborates about the creation of the city of Gloucester?

Gloucester is an important part of the story, as the “big city” backdrop where Peter first meets Barnabas and gets involved in his criminal activities. We scouted the real town of Gloucester during pre-production and gathered a lot of photo reference, but the shoot ended up happening partly in Sydney at different locations for scenes like the Farmer’s Market, as well as in the town of Richmond in south-west London for locations such as the exterior of Nigel Basil-Jones’ office.

There were a few specific areas – the laneway featuring the Tailor of Gloucester shop and the exterior to Barnabas’s hideout was a small set built at the Fox Studios in Sydney requiring blue screen extensions at either end. The Farmer’s Market was an enclosed exterior location in the western Sydney suburb of Parramatta, at a heritage building that was once a women’s prison. It looked pretty good, and appropriately English for the most part, except for the two areas where it opened out on to very Australian-looking streets.

Knowing that we’d need to patch or extend these Australian locations, we worked with Clear Angle Studios in the UK to photograph and scan large areas of Richmond while we were shooting there, focusing mainly on the inner-city laneways, open squares and small parks. The Clear Angle team also made a special trip to Gloucester to scan specific landmarks such as the Gloucester Cathedral, and a combination of these were eventually used to create the extensions expertly handled by Method Studios.

Is there any invisible effects you want to reveal to us?

It’s common stuff, and not the most interesting parts of the work, but there is a lot of simulated travel in the movie. The train journey that the characters take to Gloucester in the beginning was shot in a carriage compartment set on stage at Fox Studios in Sydney, comped with array plates shot in the Southern Highlands of NSW standing in for the Lake District. The conversation Peter has with Barnabas in the back of the Tailor’s van was shot in a stationary prop vehicle on the Fox Studios lot, using array plates shot in Richmond for backgrounds.

There are also many sky replacements in the film, as we were always trying to achieve a balance of clear sky and cloud. Full overcast skies were always patched with blue areas, and cloudless skies (a common occurrence during filming in Sydney’s hot summer) were usually augmented with clouds.

We also made many tiny adjustments to the backgrounds of shots in the city sequences. Richmond buses had their signage changed to ‘Gloucester’, walls had rabbit graffiti added to them, and we even altered the names of certain shops at Will Gluck’s request which he used as personal shout-outs to his friends and family (he loves a good hidden in-joke, there are many in this film).

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Besides the Farmer’s Market heist, which I love for just how much fun it was helping to come up with and execute all the little vignettes where the animals take out the farmers and make off with the dried fruit, my favourite sequence would probably be the montage where the kids bring Peter and Barnabas back to the house in the cage and play with them, toss them in the air, wash them in the sink and blow-dry them, dress them up in dolls’ clothes and generally rough them up.

That scene is full of super difficult and fiddly work, mostly to do with the very intense interaction with the kids. It’s pretty satisfying to see how well that scene came together after the extreme tension of shooting it, working with Simon Pickard on set to supervise the kids’ actions to make sure it was going to work for us in post. The kids were great, but they needed a lot of coaching on how to hold and interact with the stuffies so that their actions looked believable.

Separate to that, my actual single favourite shot in the movie is a quick cutaway during Barnabas’s introduction to the Farmer’s Market showing the merchant at the spoon stall demonstrating how to use a spoon to a customer (stir and slurp). Still makes me giggle every time I see it.

Simon Pickard // I’d second everything Will mentioned above, I also loved the ‘whack-a-rabbit’ scene. It was so much fun putting the ideas together for that scene; Mike Cottee the animation lead on that scene did an amazing job.

What was the main challenge on this show and how did you achieve it?

The biggest challenge of the show was in the post-production period when the movie was in a large state of flux in Editorial, and we had to find a way to keep momentum going on developing the sequences while Will Gluck and editor Matt Villa were trying different versions of the cut, adding and removing sections, shifting things around and generally trying to find the tone and voice of the movie. We would try and focus our efforts on parts of the movie that we thought were relatively stable, but sometimes large sections of work we’d developed to a fairly refined point were cut out and replaced with something new. It was a mixture of emotions because even though each time sequences we created were re-worked it felt like a setback, the movie kept getting better and better, so we came to appreciate the process despite it being stressful.

What is your best memory on this show?

One of my favourite experiences working on both this movie and the first one, was getting to play the voice of the manic JW Rooster II. I was cast in the first movie after helping out Editorial with doing scratch dialogue reads for different characters while they were assembling scenes and creating animatics for the shoot, and Will Gluck liked what I was doing with the voice of this character so much he decided to keep it in the movie. It was great fun coming back to the role for the second time – it’s extremely physically taxing, I have to scream my lungs out and I get sweaty and light-headed, plus I have a dialogue coach attempting to make sure the words I’m belting out have an English accent to them, but it’s a total blast doing it.

Simon Pickard // I was lucky enough to be involved in the Story creation a lot more on the 2nd Film which was extremely rewarding. As animators we’re always trying to value add to the shots, which Will Gluck always encouraged, but to be in the room helping to craft scenes or trouble shoot gags was an amazing experience for me.

How long have you worked on this show?

The whole production run from September 2018 until March 2020 (we finished a week before the big COVID lockdown), so around a year and a half.

What’s the VFX shots count?

There were 1295 VFX & Animation shots in the film.

What was the size of your team?

From the key companies involved – 460 from Animal Logic, 150 from Method Studios Melbourne, 35 from Clear Angle Studios, 8 from WYSIWYG 3D and 5 from Soundfirm totalling 658 all up.

What is your next project?

I’m hard at work on something quite exciting that I can’t reveal quite yet, but it’s a dream project for me and I’m very much looking forward to when it’s finally announced.

Simon Pickard // We’re hard at work on our first collaboration with Netflix on the fully Animated Feature The Magician’s Elephant directed by Wendy Rogers.

A big thanks for your time.

// Peter Rabbit 2: The Runaway – Final trailer

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Animal Logic: Dedicated page about Peter Rabbit 2 on Animal Logic website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2021