Back in 2012, Simon Hughes told us about Image Engine‘s visual effects work on Safe House. He then joined the Union VFX team. He has worked on a large number of shows, including Everest, Annihilation, Cold Pursuit and The Power.

Tallulah Baker began her career in visual effects in 2015 at Azure VFX. She then worked at MPC before joining Union VFX in 2021. She has worked on films such as Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales, The Lion King, Maleficent: Mistress of Evil and The Sandman.

How did you and Union VFX get involved on this movie?

We were put forward to the production by the team at Searchlight and pitched to the team in early 2021. We were instantly intrigued and eager to work on the project as projects like this don’t come around often.

How was the collaboration with director Yorgos Lanthimos?

Yorgos is a photographer as well as a filmmaker so is understandably all about the filmmaking process. Our initial meetings were very exploratory – questioning all the different possible approaches. He referenced a lot of period production techniques such as painted backdrops and miniatures. He wanted all the environments to have a ‘painted’ quality regardless of how they were created.

A lot of our conversations revolved around how to piece together these more traditional filmmaking techniques with our VFX approach to end up with something photoreal enough to sit in with everything else that was captured in camera while maintaining a miniature scale. We looked at a lot of films that had used miniatures, particularly those that had used water, including a 1953 version of Titanic and questioned what ‘felt’ miniature and which things we’d need to be on the lookout for to ensure our amalgamation of techniques was working.

What was your feeling about entering this particular universe?

From our first conversations in early 2021, it became very clear that Poor Things wasn’t going to be a typical world-building exercise. It was exciting.

What was his approach and expectations about the visual effects?

The director didn’t want to over-rely on VFX, but to find a perfect marriage between period film production techniques and VFX to create something original and unique.

How did you organize the work from a VFX Production point of view?

Tallulah Baker // We were involved with Poor Things from quite early in pre-production. We had a fair bit to do before the shoot as we had to plan, build and deliver the environments for the enormous LED screens as well as suggest and test approaches for the Hybrid animal work.

It was my responsibility to ensure the project was budgeted, resourced and managed as efficiently and productively as possible throughout. I worked very closely with the production’s team as well as our internal creative and senior management team.

The creative nature of this project required a lot of slightly out of the box thinking and trial and error, but was also a truly unique undertaking. We had a lot of fun breaking the normal rules of VFX and coming up with names for our hybrid animals.

Can you elaborate on the design and creation of this surreal world?

We were involved early and collaborated closely with the production designers Shona Heath and James Price and we worked together to develop their ideas and help envisage how they could be translated into achievable VFX. Shona has a fashion and set dressing background and has a very strong surrealist aesthetic. James is from the film world and together we made an interesting, creative team.

What kind of references and influences did you receive to create this world?

The team brainstormed a lot of approaches to the environment oceans and skies, which needed to be surreal and work at both miniature and ‘real’ scale. We presented some previous water tank and liquid experiments shot in slow motion along with similar examples from within the art world, to the production team leading to a collaboration with artist Chris Parks.

Did you use any miniatures?

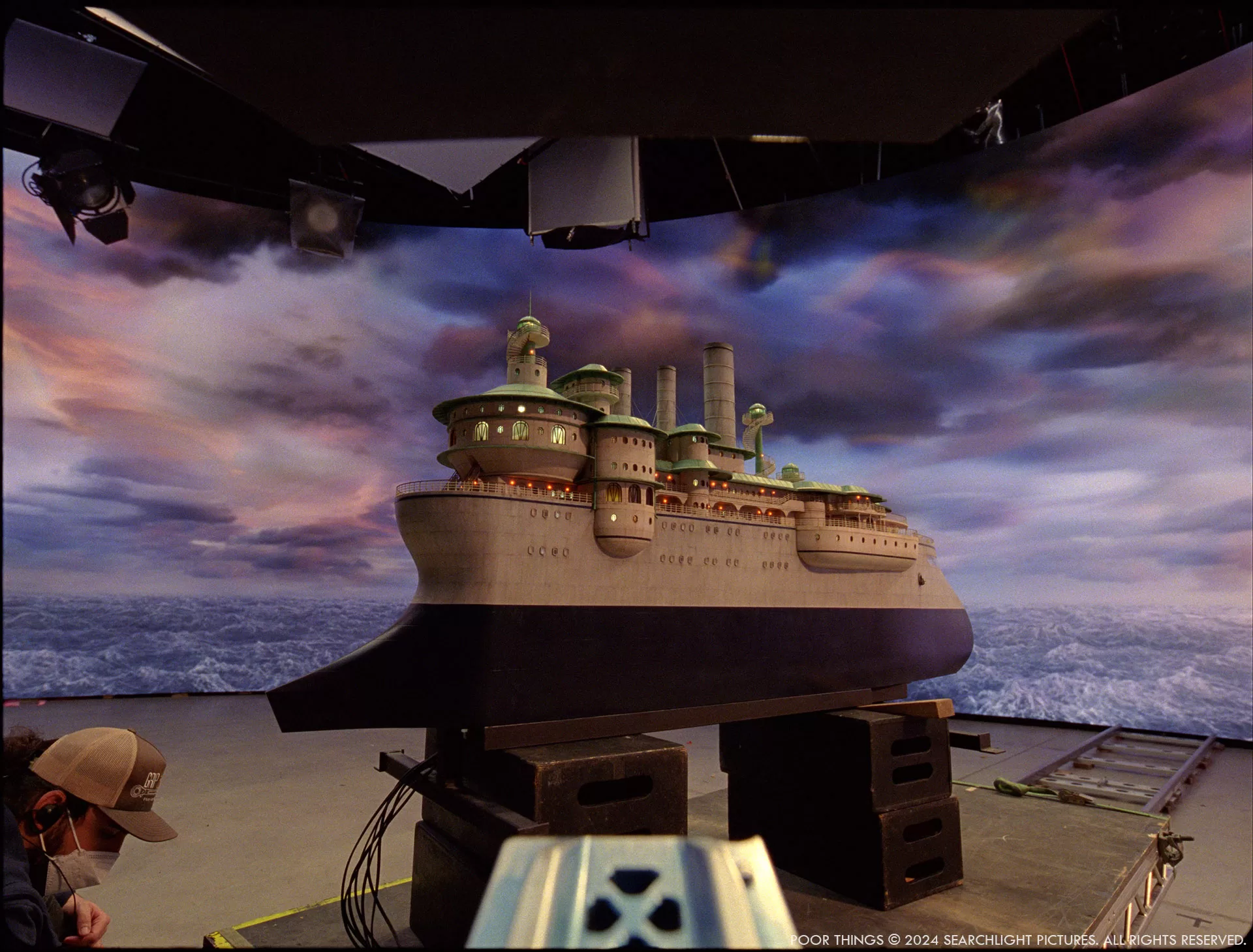

There were miniatures of the ship as well as London Bridge, Alfie’s Mansion, Alexandria and Lisbon.

What was the most complicated thing or location to create?

The most complex location to create was Alexandria.

Alexandria is a real amalgamation of miniatures, with live action life size sets and CG environments. Initially, Bella looks down at the slums before running down the stairs. We then do a big long pullout reveal of the island. Both those key shots had miniature builds: the architecture that she’s in and the stairs that she and Harry are sitting on. There was also a set build for that specific section of stairs.

Marrying the worlds together–real-world scale and miniature scale–had some technical challenges. We used some re-projections, extracted the actors at a certain point and re-composited them onto a LIDAR-scanned version of the model set so that we could control the camera move. As much as we love the models, there’s a certain point where you want to give them more. They lack some definition in areas and we added some digi-doubles in there as well as palm trees, greenery and a cable car system running in the background. So, it starts as a miniature, but we scan that model, bring it into CG, work it up and add all these extra layers and then merge them together.

Additional details such as sprites of characters in the slums (including animals) CG people, CG oceans with a miniature scale, a different cable car system to Lisbon which also needed to have plates of cast members composited within. All of which was covered in a thin layer of dust and sand from the air to make Alexandria feel dirtier and hot.

Can you tell us more about the use of the LED walls?

We created sky and ocean environments for use on set, mainly for the journeys that take place during the film – we visit Poor Things versions of Paris, Lisbon, Alexandria and London. We came up with a series of 50-second ocean variations: choppy water, calm water and different versions for times of day etc. which could be called up on the LED screens. We also created 11 different sky variations, which were then set up with those same motions, so they reflected correctly. Those were 24K renders, which were projected onto 11 absolutely enormous (70m x 90m) wrap-around LED screens in Budapest at Origo Studios. It was quite a challenge just getting that footage rendered, set up and delivered to them in a way that everybody could actually use because 24K is quite intense.

On the creative side, they wanted a kind of bizarre underwater quality within the skies to fit into the surrealist world. Yorgos wanted to explore a hyperreal quality and different ways of making the skies feel surreal. I had previously done a slow-motion shoot of Dettol in fish tanks where we squirted it and observed how it moved. We showed these at slow frame rates to Yorgos and he really liked the idea.

I love how it moves because it feels like clouds, but there’s something weird about it that gives it a miniature kind of feel. We did a bit of research into artists using similar techniques and found that there are a lot of artists exploring this.

As mentioned, we collaborated with artist Chris Parks who has created a whole host of these strange liquid experiments. He allowed us to experiment with his work within our skies at low resolution. We’d drop them behind real skies and put them in the deep background. Once we worked out which things worked well, we could request them at higher resolution and work them up.

The choice to shoot LED proved a good one as the sets inherited their ‘natural’ lighting, but this was also challenging in some places as the LED footage needed re-composited to further augment ocean and sky movement – especially when sailing. We also had to address the inevitable fixes that come up when shooting this way: moiré, seams between screens, shooting offscreen due to the sizes achievable etc.

How does the specific frame aspect affect your work?

I won’t lie, it was definitely a challenge working with a fish eye lens. De-lensing those plates creates a huge resolution. There’s a certain point, when running a lot of the tools that we normally do, we were getting some quite strange distortions towards the edge of frame. Sometimes they were actually cropping off. There was a lot of head scratching to figure out how to get a decent de-lens so that we could matchmove things and get things sticking correctly.

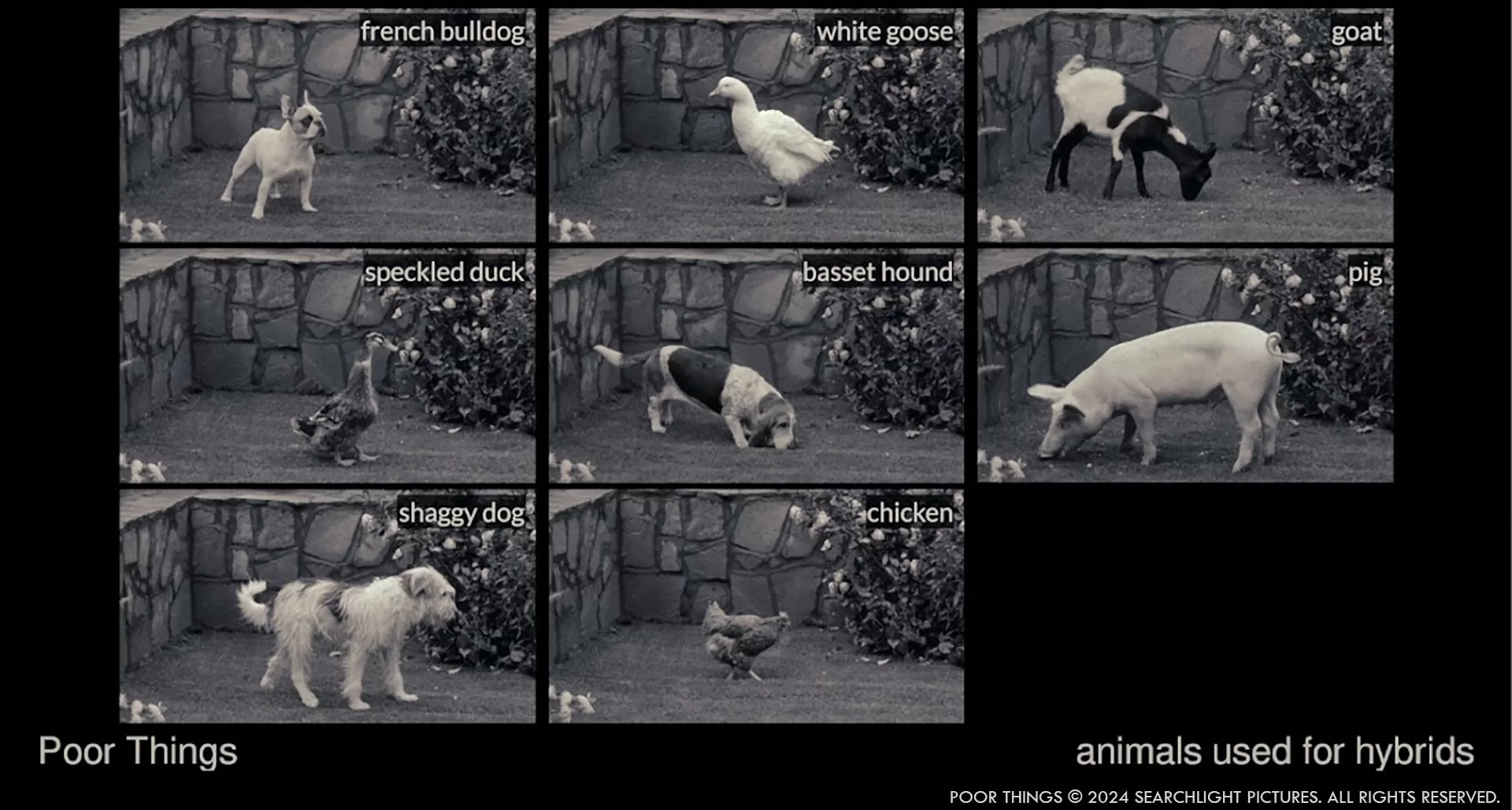

Can you elaborate on the design and creation of the animals?

When we started talking with Yorgos most people were automatically suggesting it should all be done digitally, but he really didn’t want that. He wanted to know what he could get from real animals. How we could make that work.

One of the main reasons we were awarded the work on Poor Things was because we believed it could be done, but it was going to require a bit of trial and error as well as some risk. Animals do what they want to do, so we knew we were going to have to lean into their behavior a bit and work with it. Yorgos was all for that because it leaned into the surrealism of the whole project. He liked the unpredictable nature of the animals as it reflects the film’s ethos in many ways.

We suggested getting together with the animal wranglers and having them show us what they thought they could get the animals to do. Firstly, just walking from A to B, and then with somebody actually standing in front of them trying to hand them something.

We then did camera tests, trying to work out what would be the best combinations of animals while also pushing it – pairing animals that really shouldn’t be together so that it’s obvious that there are different connections. We were trying to find animals that are different enough, but at least have a certain point in their body that could act as a good connection point with their counterpart.

We basically overshot it, knowing these animals would just do whatever they wanted to do on the day. We got lots of variations of animals walking then we brought the footage into the edit and spent hours and hours trawling through trying to find those rare moments where you get a good connection.

We always knew there would be a CG requirement, but we wanted to go as far as we could with real plates. Quite early on, even with the early comps, we could see things were working. The technical challenge came when adding the surgical scars to the animals. We scanned all the animals, which is an interesting challenge in its own right.

We then brought the models into CG and rigged them. These were very unique rigs. We had the models of two different animals and then overlaid them over the image. We gave that to a rigger and they learned to create rigs for hybrid animals which were then passed to matchmove, trying our best to get a good rotomation of the combined animal. It had to be done in several stages: matchmove would do a pass, hand it back to comp, and then comp would do a pass on that to tighten things up until we got to a good place.

I’m really glad that we went down the photography route and totally agree with Yorgos’ inclination. If it had been done as full CG, people would be picking on them and questioning their movement etc. But we can always stand behind the fact that they are ‘real’ animals and behaviours. I think it’s really clever and love the final result.

There’s a lot of nuance in the way they move. You can do the best you can to recreate that, but there’s a lot of independent detail that you might not be aware of. To have that on film is great. I’m a big fan of it, personally.

The creatures were very popular in the studio where we affectionately named them: Goose Willis, Bark Wahlberg, Bill The Kid, Sirius Quack, Six Sox and David Eggham.

Did you want to reveal any other invisible work?

Paris involved set extensions up and out from the buildings around the brothel. We also needed to take the painted backdrops out and bring them back with additional signs of life and a more defined Eiffel Tower under construction in the distance.

Another set, not yet mentioned, is Alfie’s mansion, which is one of the standout examples of combining miniature set builds with CG, matte painting, plates of the cast, birds, trees, colourful smoke stacks, flags from masts all of which needed to remain in our miniature surreal colourful world.

There is a series of shots showing the surreal ferry boat travelling between locations. This again was a miniature build that we needed to augment and integrate with the live action plates and CG miniature scale water.

For the Lisbon cable cars, we had pole systems which ran the cable, so when they hit the poles and turned a corner, we had to work out the right feel for the wobble so that it still felt like it was a miniature. There were quite a few iterations on that to get it to where we were happy. In the big wide shot of Lisbon, when Bella is standing on the balcony and you see the whole world there, a significant part of the architecture was based on a miniature, but we also had to project a lot of that to add into the CG. It’s kind of tricky with the cable cars because you start with them in the real world and then travel into a false perspective, a kind of 2D world. It was a challenge to get the animation on that right as you transition from the real into the fake.

In the deep background, there were a lot of hot air balloons. We also had Zeppelins in London. Even though they sit in 3D space, it was fun to do a bit of cheating on them to maintain that ‘painted’ backdrop feel, even though you want things to move correctly. It’s quite a surreal challenge. It’s interesting for the artists working on it because we’re so versed in focusing on things being in perspective with everything correct, lighting correct, but then here we are asking the artists to break those rules.

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

There were two fundamental challenges on the show: creating the hybrid animals and building a world that maintained a miniature surrealistic feel while also feeling photo real. The latter is a contradiction in a way, making it incredibly difficult to know when it is working well and how far to go, but a really fun challenge that pushed us to set a new bar for the work we do at Union.

What is your favourite shot or sequence?

I’m really proud of all of our work on this unique project, but do have a soft spot for David Eggham (the Chicken/Pig) and Alexandria.

What is your best memory on this show?

This was such a unique project to be involved in and we really got to flex our creative muscles collaborating with the amazing creative team to produce such a stunning film. Everyone involved is at the top of their game and pushed even further to create the truly unique world that is Poor Things.

Union have a reputation for ‘invisible’ or ‘seamless’ VFX and this is quite a different representation of that. There are those who won’t think of Poor Things as a ‘visual effects film’ and there is quite a lot of debate around that at the moment, but VFX are a key piece of the puzzle in making almost all films and this project is a great example of how they can be part of getting such an imaginative vision onto the screen.

How long did you work on this show?

Tallulah Baker // We started talking to the team in March 2021. The shoot happened in the midst of Covid, which required additional planning and logistics. We also had to build and test the LED environments. We did five weeks of prep and testing in August and shot September to December. We didn’t start VFX in anger until late 2022 as Yorgos filmed another project and delivered in June 2023.

What’s the VFX shot count?

Tallulah Baker // All in all seventy artists worked on the show at various points during this long pre-to post-timeline and delivered 177 shots, 11 Led skies and oceans, and 60 assets.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Union VFX: Dedicated page about Poor Things on Union VFX website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2024