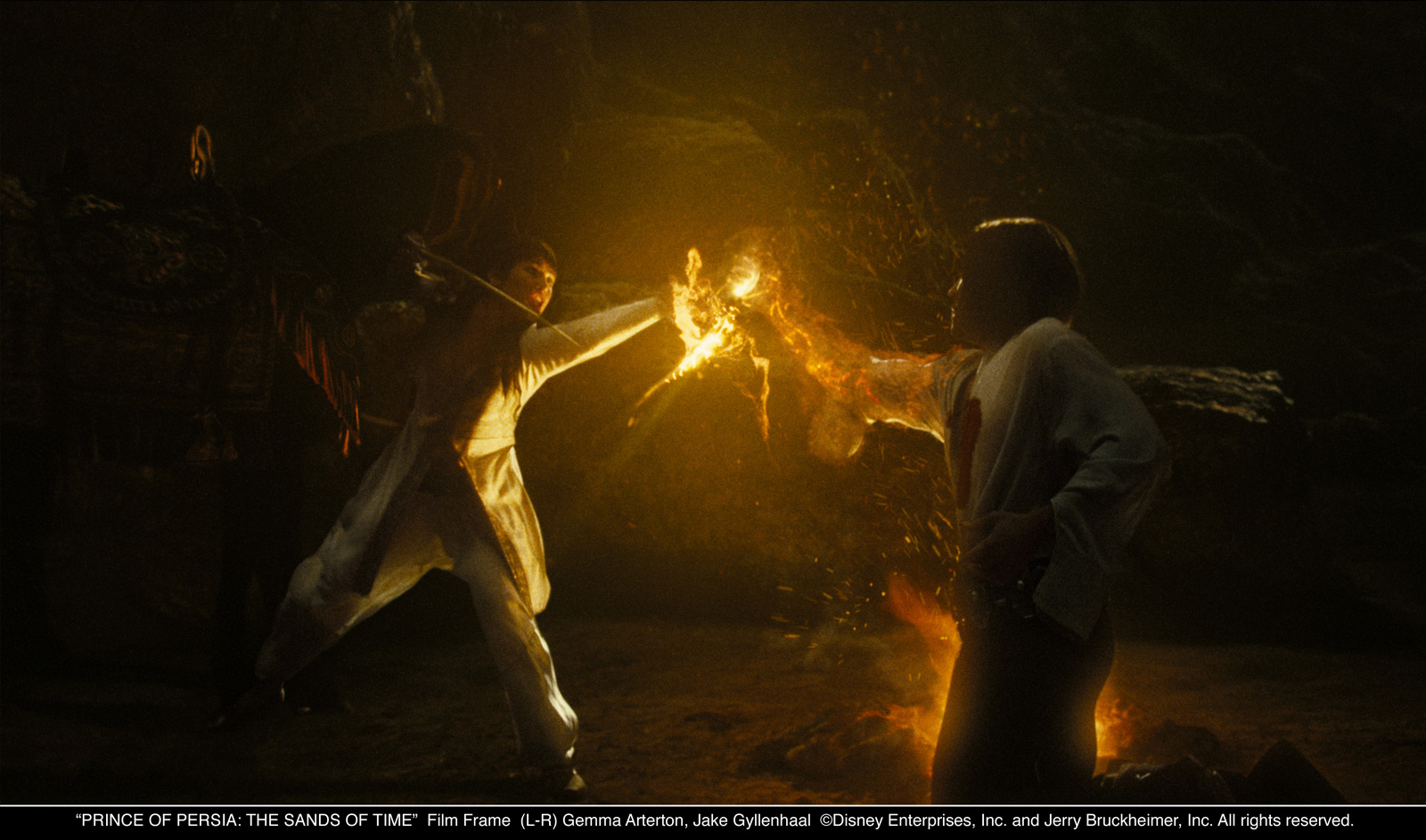

Michael Bruce Ellis worked for over 10 years at Double Negative, he begins at the roto department of the studio and then quickly rise and is visual effects supervisor on movies such as WORLD TRADE CENTER or CLOVERFIELD. He recently completed the visual effects of PRINCE OF PERSIA.

What is your background?

I began my career as a graphic designer in TV, working on Channel Identities, Promos and Title Sequences. I switched career in 1999 to join Double Negative’s 2D department as a Roto Artist. Apart from a short stint at Mill Film to work on one of the HARRY POTTER movies, I’ve been at Dneg ever since.

How was the collaboration with Mike Newell and the production VFX supervisor Tom Wood?

Mike Newell is a great Director who is very focused on storytelling and the actor’s performances, he’s not so concerned with the minutiae of visual effects. Tom Wood had a great deal of input in coming up with creative solutions, we had a lot of scope to try out ideas and concepts although rule number one was always that the storytelling is crucial and cannot be obscured by the images, however beautiful!

What did Double Negative made on this show?

Dneg were asked to work on 4 main scenes in the movie, which involve the “magical” aspects of the story. The three rewinding scenes when the dagger of time is activated and the climactic Sandglass end sequence.

We had around 200 shots, which took us 18 months to complete.

Can you tell us about the visual design of the slow motion effect?

Early on in the project we’d discussed creating a very photographic open shutter look for the “rewind” effect. Tom Wood had given us reference on long exposure photography in which a moving subject creates a long smear effect as it moves through frame. This had been done before with static objects frozen in time using an array of several stills cameras with long exposures, which we’re then cut together to make a consecutive sequence. But this gives the appearance of a camera moving around a frozen object, we wanted the camera moving around a moving human form that had a frozen long exposure. This, as far as we knew, had not been done before so we needed a new technique in order to achieve it. Lead TD Chris Lawrence began exploring a technique called Event Capture to see if it could help us achieve the look we wanted.

Can you explain to us what it is and what it can do?

We’d done some work previously on “Event Capture”. The QUANTUM OF SOLACE freefall sequence used the technique, then we developed it further for PRINCE OF PERSIA, it allowed us to achieve something that couldn’t be done any other way.

This is a technique which records a live scene using multiple cameras, then reconstructs the entire scene in 3D, allowing us to create new camera moves, slip timing of the actors, change lighting, reconstruct the environment and pretty much mess around with whatever we wanted.

The technique works by shooting the action with an array of locked cameras set in roughly the path that you plan your final camera to move along. We ultimately used a maximum of 9 cameras at a time. Precise calibration of camera positions, lens data and set details allows us to combine all 9 cameras to reconstruct a 3D scene which has original moving photographic textures.

As our new 3D camera moved around the scene we transition between each of our 9 cameras to give the most appropriate texture. One problem we found with this technique is that as our photographic textures are derived from locked camera positions, specular highlights tend to jump over an image rather than smoothly roll over a surface as they do in real photography. He had to correct this by manually painting out such problems.

The great advantage of this technique was that it answered all of our technical requirements while giving us great creative freedom. With some restrictions based on texture coverage, we could essentially redesign live action shots after they’d been shot. The camera is independent from the action. A camera move can be created after the shot has been filmed, actors’ timing can be slipped and they can be manipulated to break them apart or change them as if they were conventional 3D.

Can you explain us how was the shooting for the slow motion sequences?

Each rewind scene is constructed so that we see a regular piece of action leading up to the dagger being pressed, the action then rewinds to a earlier part of the scene then the action plays forward again with an alternative outcome.

The rewind effects work had to fit seamlessly into a regular forward action scene and we’d need the actors to repeat everything as closely as possible. It seemed like the most logical thing to do was to shoot the rewinds straight after the forward action as it appears in the movie. The actors still had the moves and performances fresh in their minds and we could shoot with the same sets and keep the lighting set-ups as similar as possible.

The technique we were employing required clean, crisp photography with a minimum of motion blur but a maximum depth of field. This gave us a better result when projecting our 9 cameras onto 3D geometry and was valuable in creating convincing new camera moves as it meant that we could apply our own motion blur and depth of field.

This was a problem because we’d need a lot of light hitting our subjects and all of our rewind scenes occurred at night or indoors. John Seale and our VFX DoP Peter Talbot came up with a way of boosting the scene lighting universally by 2 to 4 stops. It meant that the rewinds could keep the same lighting feel with shadows and highlights matching the forward action but give us the best possible images to work with.

So it was really the transition in the shoot schedule from Forward action to Rewind Action that took the longest time to set up because we had to accommodate this boost to the lighting. As soon as we had the first rewind set-up in the can, the others followed much more quickly. We’d carefully planned the position of each camera and marked up the set accordingly so we were quickly able to set-up our cameras for each shot.

Did you create digital doubles for these sequences?

Yes but not in the conventional sense. Event capture gave us a digital human form for each of the actors. But the process is not perfect and we still had to do a lot of body tracking. We ended up with grayscale Digi-doubles onto which we projected moving textures from our 9 cameras, giving us real photographic textures on very accurate 3D human forms.

Can you tell us how you create those beautiful particles?

Our effects 3D supervisor Justin Martin and 3D leads Eugenie Von Tunzelmann, Adrian Thompson and Christoph Ammann developed a look and technical approach for the particles. All of our sequences revolved around the magic sand and we wanted the viewer to feel that they were seeing the same substance in the intimate rewind shots as in the wide sandglass chamber shots. When we’d created a 3D figure with full photographic textures and a new camera move, we were free to try numerous creative ideas for both the rewind trail effect and the ghost particle effect. We did some work in streamlining our particle set-up, we did tests to push up the amount of particles we could render to a billion. In the end we found that we didn’t need that many with about 30 million particles on the ghost body and 200 million airborn particles. We found that we could create very organic magical particles using Squirt (our own fluid sim) and Houdini.

How did you work with Framestore (which made the snakes) for the Oasis sequence?

Maya scene files and rendered elements were passed backwards and forwards between the facilities. In some of the shared shots it proved more efficient for dneg to take the shot to Final, in others it was Framestore. We just kept an open dialogue between facilities to keep work on shared shots flowing as smoothly as possible. For the rewind shots it made sense for dneg to create a camera move then pass that over to framestore to render a snake which we’d then get back both comped and as an element, in order to create rewind trails.

The final scene is really very complex. How did you achieved it?

The brief for the sandglass scene at the end of the movie was to create a digital environment that felt 100% real yet had an enormous light emitting crystal tower in the centre filled with moving twisting sand. The sand at times needed to present images from the past inside the crystal. And the chamber has to be collapsing all around the actors. Also if that wasn’t enough the sand inside the crystal had to escape and start destroying everything, barreling into walls and knocking down stalactites.

We knew we could create the underground rock cavern but the crystal was a bigger challenge.

What does a 300 foot crystal filled with light emitting sand look like?

We looked for reference but there really isn’t anything, it wasn’t ice. The closest thing we found was some giant underground crystals but they just looked like a photoshoped images.

In the end we went out and bought a load of crystals from a local New Age store, we shone lasers through them, lit them with different lights and played around with them copying what it was that made them feel like crystal, the refraction, the flaws etc. Peter Bebb, Maxx Leong and Becky Graham used this and built an enormous version of it.

The biggest challenge of this sequence was achieving the scale, the crystal is such a crazy object. We went to a quarry in the UK and took lots of photos. We reconstructed the rock surface in 3D and projected textures onto the geometry, so that it became a very real rock surface built to a real scale.

Another thing that helped us with scale was adding all the falling material. Christoph Ammann and Mark Hodgkins spent a lot of time working on the way that rocks would fall from the roof and break up and how they would drag dust and debris with them. Getting the speed of falling material right really helped with our scale, adding atmosphere also helped, we added floating dust particles which are barely readable but which kind of subconsciously add a feeling of space and distance.

What was the biggest challenge on this show?

Our most challenging role on PRINCE OF PERSIA was to create the Dagger Rewind effect.

Our brief for the Dagger effect consisted of three main requirements, which were needed to tell this complex story point.

The person who activated the dagger needed to detach from the world so that they could view themselves and everything around them rewinding. We as the viewers needed to detach with them so that we could see the rewind too. We needed a way of treating the detached figure to tell the viewer that he is no longer part of our world. We called this the “ghost” effect.

The world that the ghost sees rewinding needed to have a signifying effect which would show us that it was the magical dagger that was rewinding time. When the dagger is activated we needed to see people moving in reverse in a magical way. We called this the “rewind” effect.

The dagger needed to change the whole environment in some way when time is rewinding so that we could clearly tell the difference between rewinding shots and regular forward action shots.

So we needed an approach to the Dagger Rewind effect which could achieve all of these things. The same actor would need to appear twice in many shots moving both forward and in reverse simultaneously with 2 distinctly different looks, the “ghost” and the “rewind” effects. We’d need to freeze and rewind some aspects of the same shots. We’d need to relight scenes.

On top of all of this, we knew that we’d need an approach that was very flexible. We knew that the choreography of each shot was going to be very complicated with inevitable changes to actors positions or camera moves needed to help convey the story as clearly as possible. Who was standing where, which direction are they moving in, are they in regular time, frozen or in reverse were all questions that could be answered at the previs stage but we knew that with the addition of the “looks and effects” that we wanted, this choreography would probably need to change a little after shooting.

How many shots have you done and what was the size of your team?

200 shots with a small team, which ramped up to around 100 artists at our busiest time

Was there anything in particular that prevented you from sleeping?

The most difficult shot occurs when Dastan activates the dagger for the first time, bursting out of his body as a particle ghost and watching himself rewind in time. The shot travels from a mid shot to extreme close up then back out to a wide. We had to design everything about the shot. Its fully CG and we get very close to Dastan’s face who had to be completely recognizable. It’s also absolutely covered in particles, which the camera passes through. Editorially we had to tell a crucially important story point, creatively it had to look magnificent and it was a huge technical challenge. Yep…a little lost sleep on that one!

What are the four films that gave you the passion for cinema?

JAWS – I love everything about it…particularly the rubber shark.

ALIEN – Giger and Scott made this movie feel like it came from another planet!

BLUE VELEVT – Lynch really gets under the skin

THREE COLORS trilogy – beautiful movies

SOME LIKE IT HOT – can’t stop at 4

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Double Negative: PRINCE OF PERSIA dedicated page on Double Negative website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2010