Martin Hill began his career in VFX at Double Negative, where he worked on films like BELOW, THE CHRONICLES OF RIDDICK or BATMAN BEGINS. He then joined Weta Digital for KING KONG. He worked on many projects like ERAGON, AVATAR, RISE OF THE PLANET OF THE APES or THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN.

What is your background?

Originally I studied Architecture, then Mathematics at University of Edinburgh and then an MSC in computer animation at Bournemouth University. After graduating I worked at Double Negative for four and a half years before joining Weta Digital as a TD on KING KONG, after which I spent 5 years as the Shader Supervisor which included films such as AVATAR and THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN. PROMETHEUS is my first show as one of Weta Digital’s Visual Effects Supervisors.

How did Weta Digital got involved on this show?

We were first approached in December 2010. Ridley had an early design for the engineer and had a maquette which he lit, put on turntable, shot some footage and sent it to us to see if we could match it. We built the model digitally from scans, recreated the material properties of the skin and added a facial rig so that we could articulate the model and bring it to life. The results gave Ridley the confidence to pursue using digital creatures for the film.

How was the collaboration with director Ridley Scott and Production VFX Supervisor Richard Stammers?

Ridley has a really strong vision in terms of what he wants, but is also very open to have ideas presented to him, so we were able to get involved with the design process and how creatures would move and look on some of the sequences. In some instances there was a creature that already had a maquette built and had a design which we would match and enhance to make sure it was able to articulate in a realistic way, where a puppet was more rigid or unnatural. In conjunction with Richard Stammers we were able to collaborate and design the vision that Ridley wanted.

What was his approach about visual effects?

Ridley likes to shoot as much practical as he possibly can; he much prefers to capture in camera than use CG. This has a lot advantages because it means that his images are real, his actors are responding to real events, not to green screen. It also means he can direct in the style he is used to. As much as possible, even when it was clear we would be replacing something digitally, he would have a physical maquette built – something tangible and real – which would help with the design process.

What have you done on this movie?

We worked on the opening sequence with the transformation and destruction of the engineer and his DNA, the medpod scene with the C-section of the trilobite, a fully digital Fifield monster, the engineer vs trilobite fight, the ‘birth’ of the deacon and the reveal of the Pilot’s Chair, and numerous spot effects and set extensions.

Have you enhanced the beautiful environments of the opening sequence?

The Dettifoss Waterfall is a beautiful location, which really didn’t need a lot of enhancement, so we did mostly interaction work, for example replacing the sky where the ship flies through the clouds disturbing them. There was a lot of grade work by Christoph Salzmann, the comp lead of this sequence. We also had to paint out a man walking his dog! We did have to recreate part of the waterfall when the engineer splashes in. We couldn’t throw a practical element into the waterfall for the interaction as it’s a place of natural beauty. We had to digitally recreate the flow and choppiness of the waterfall digitally to be able to simulate the splashing and interaction of the engineer.

How did you create the digi-double for the Engineer?

The engineer had unique challenges. Usually we would strive to make a digi character as anatomically accurate as possible in terms of its musculature, articulation, and the thickness and pliability of the fat under the skin. For continuity with the practical plate we had to make some compromises to match an actor in silicone prosthetics. For example, because the silicon was so thick, we needed to increase the depth of our subsurface vastly, which causes problems with light bleeding through areas like the bridge of the nose and the fingers, making him look waxy. To counter this we added an extension to our TDQ subsurface plugin written by Eugene D’Eon, which added internal blocking structures to the model. Our creature’s supervisor Matthias Zeller had to augment our muscle system to make some of the muscle contractions and tendons less pronounced to match the performance on set.

The Engineer got contaminated. How did you design it and create this effect?

Taking Ridley’s lead, we endeavoured to use as much reality as possible. We shot a lot of practical elements that we used either directly in our comps, or indirectly as driving mechanisms for a more natural texture, feel and motion.

The effect needed to be aggressive and visceral, whilst still looking plausible. It also had to keep escalating, each shot being visibly more advanced than the previous. For the start of the disintegration, the black goo the engineer drinks is swiftly transported around his body using the vein and nervous system. We took silicon blocks, carved vein structures into them and pumped through oils and inks. We backlit and filmed these elements which were then post processed and used to drive procedural shaders that created the displacement and colour of the effect, and also secondary effects such as bulging veins which would become materially more specular. The same elements processed with a delay would also drive bruising and bursting capillaries. This effect was led by CG supervisor Thelvin Cabezas and Shader Writers Remi Fontan and Chris George.

As the effect increased, the skin would dry out and become cracked. Again we used practical filmed elements (such as drying paint and clay) as drivers for the digital cracking effect and the skin becoming hard and leathery. The same elements were also used to drive sculpted atrophy deformers of the engineer created by Models supervisor Florian Fernandez’s team. Having multiple layers of the effect driven by the same mechanisms, helped create the natural feel.

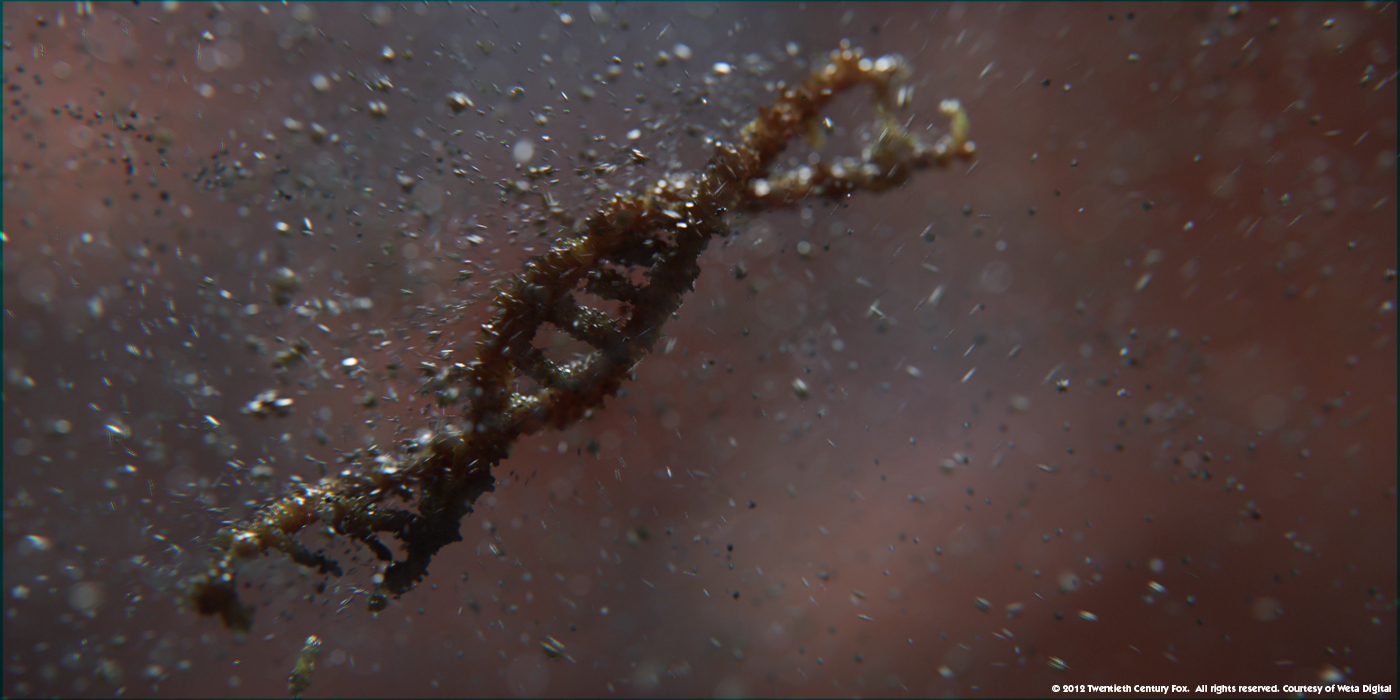

Can you tell us more about the shots showing the transforming DNA in the water?

We had to design three types of DNA. The engineer’s DNA, the infected DNA and the ‘Earth’ DNA. We got a first brief from Ridley about the first DNA transition in which he said ‘It’s like war in there’. For the engineer, we had to create quite a sinister looking DNA for which we used fish spines/bones as practical reference. They are very translucent and so you really get the contrast with the infection. For the infection we based it on some practical animations using melting polystyrene to give it its infected look and animating shader work by Masaya Suzuki.

As we enter the arm, we travel through a very large particle sim for the blood and internal structure of the veins of the arm until we get down to the cellular level, where we can actually run along the strand of DNA following the infection until the DNA is smashed apart, using a rigid body sim by FX TD Francois Sugny.

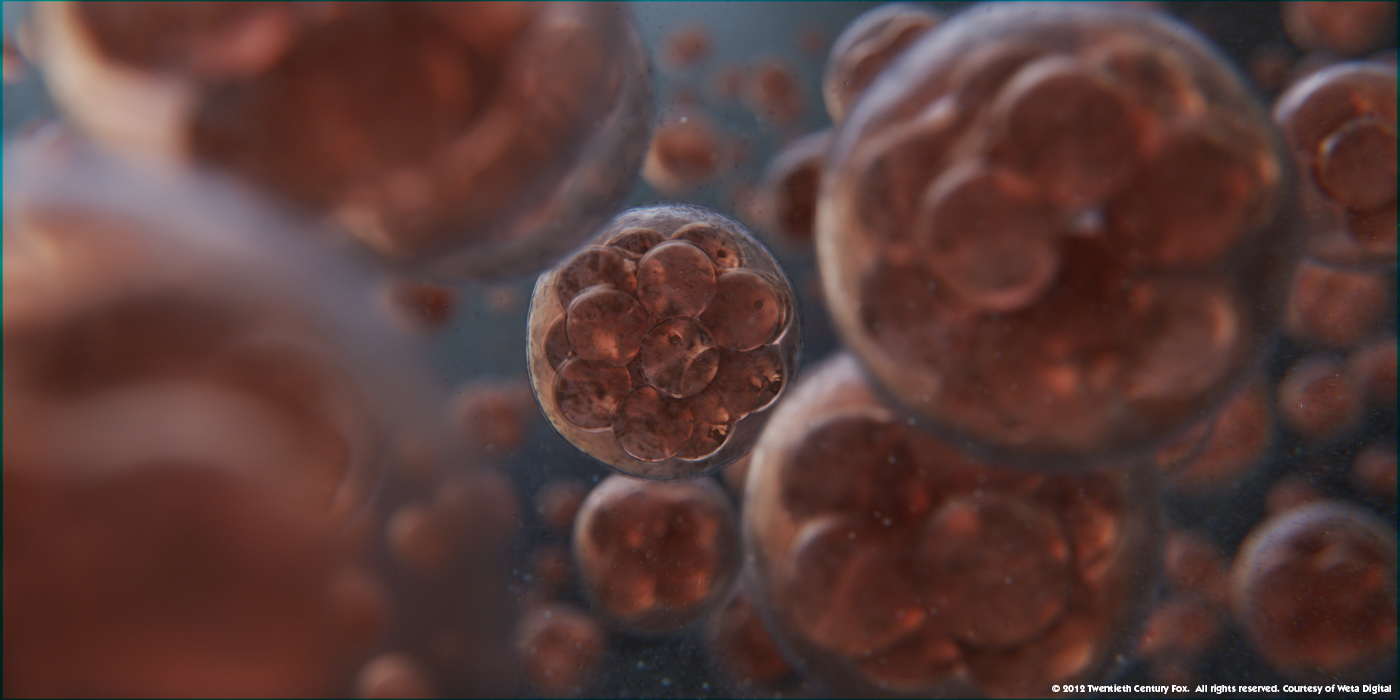

The second DNA sequence uses the broken pieces from the first in a particle system in a very different colour palette. The first DNA sequence is very dark and destructive in tone, the second has much warmer tones and is all about rebirth and having the broken part of DNA reforming into a softer looking DNA structure, from which we refocus out on to the cells undergoing mitosis which were animated with a tight collaboration between the animation team and secondary procedural animation by FX TD Brian Goodwin within Houdini.

What was your collaboration with Neal Scanlan’s teams for the creatures and especially the Trilobite?

Neal’s team built a fantastic animatronic for the baby trilobite. It had a huge amount of articulation and it was very flexible with a very organic looking motion to it. This was used directly in quite a few shots and gave us a really good foundation for where we needed to replace the trilobite digitally.

We took the cast of Neal’s teams’ models for the internal and external structure of the baby trilobite, rebuilt these in CG and rigged the trilobite digitally in the same way as the armature. This meant that we were able to get the same range of motion but we could also perform more precise and extreme poses than was possible with the practical model. Basing our digital model on the prosthetic made it easier to cut seamlessly between the digital model and the practical model.

The Med pod sequence is really intense. Can you tell us about the medical instruments that operate on Elizabeth?

Ridley wanted the machinery to move in a disconcerting and sinister way. We looked at reference of the motion of industrial machinery such as car manufacturing robotic limbs, and motion control cameras – particularly the way the camera head can keep completely still and controlled while the rest of the machines limbs are moving furiously around.

We augmented motion slightly to make it a little bit more sinister, often having more tools than were necessary for the shots medical procedure to create some extra claustrophobia. To give the stapler more impact we added some elements from pneumatic drills, making the whole shaft move to make the tool seem more forceful and give it more weight. Alfred Murrle and Phil Leonhardt’s team digitally projected Noomi’s body in a 2 1/2D way onto the matchmove geometry so that we could compress where the stapler was punching into her, the staples take some time to settle back to their rest state.

Have you create a digi-double for Elizabeth?

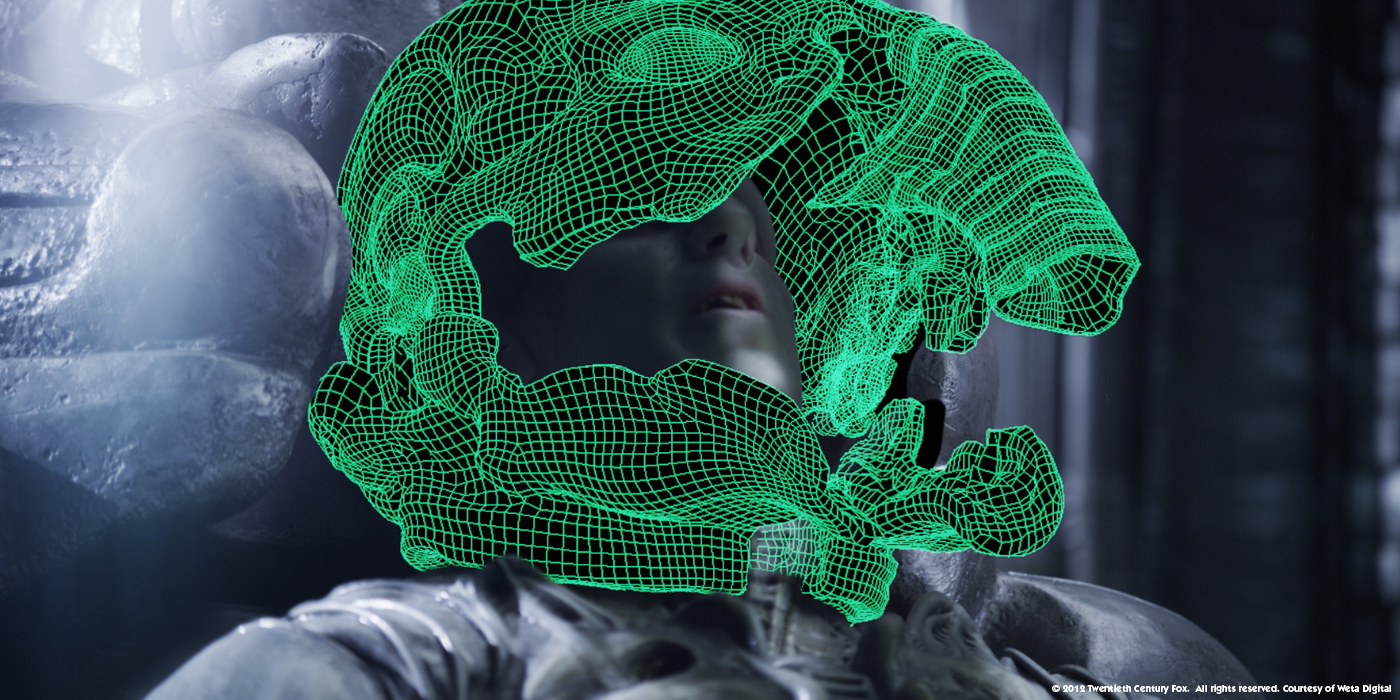

We created two kinds of digital doubles. One was for the match moves for the trilobite fight at the end – we needed to be able to wrap the creature’s tentacles around Noomi’s legs so we needed a full digital model which animation could pose the trilobite to, and also our creature deformers had something to grab hold of to know where Noomi was in 3D space so it could press against her body.

For the med pod sequence we needed a high-res geometry for her torso for which we could cut open, stretch and deform as the trilobite is pressing against her skin from the inside, for which we re-projected the plates back on to. The team then re-applied the specular highlights to match the augmented motion.

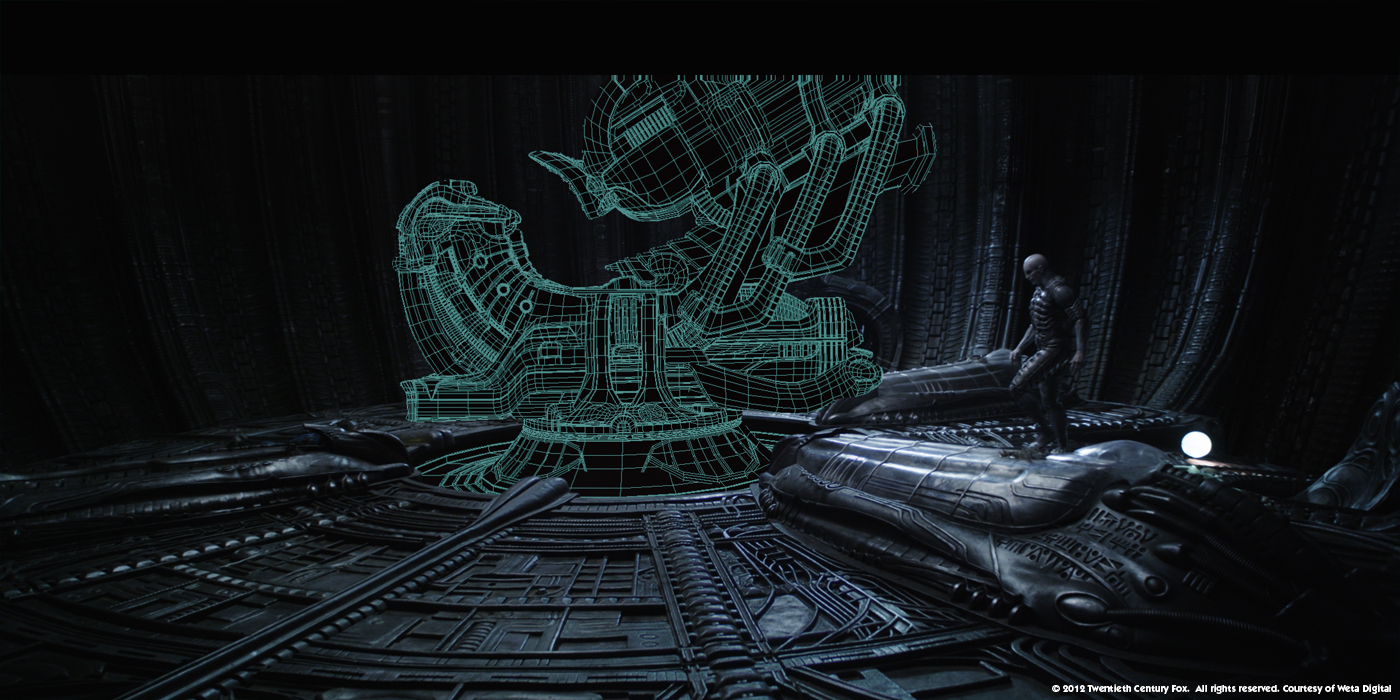

What was your feeling about bringing back to life the mythical Space Jockey chair?

It’s a real thrill to be able to work on something so iconic, which has been a mystery since 1979. Who is the space jockey? Is that skin or armour? What is the chair for? To build it in CG and work out how the elephantine suit encases the engineer, or how the chair articulates was something we put a lot of thought in to because it is such a revered piece of cinematic imagery. We knew that what we did had to look really special.

How did you design and animate the chair?

The design is from the original film and they built one on set. It could rotate in place, but the barrel of the chair and the helmet were fixed, so we needed to figure out how the articulation was going to work. We looked at all the struts on the side of the chair and worked out a way that all those things would interact in motion. One of the things that was interesting about the chair was in order to give it the biomechanical look that honoured the onset design, we had to add some distortion to our models so that they didn’t look too perfect and too mechanical and they retained the organic feel of the original film and the practical chair. This was the case with a lot of the Engineer’s biomechanical structures. Also the practical elements had a retroreflective quality to them, caused by graphite powder used on set. We had to write custom shaders to achieve this look.

At the end, the Engineer is fighting with a big Trilobite. Can you explain to us in detail its creation and the challenge of rigging?

With a tentacled creature, it is always a big challenge to create an animation rig that doesn’t collapse or twist, but still gives the animator full control of where the tentacles go. Also making sure that the stretching is even across the tentacle and that one section doesn’t get stretched more than others around it, which defies the elasticity of the creature and makes it look unnatural. On top of this, where a tentacle is wrapping around the Engineer or pinned to the floor it needs to fix there, but also needs to be able to compress and deform against the surface it’s touching. Matthias Zeller, our Creature’s Supervisor used the layered deformer approach to the muscle rig that would fire the muscles in tension and relax them in compression. This was then passed through to a solver, which would wrinkle skin where it was more heavily compressed. Where it is stretched it would wrinkle along the tentacle. These same tension and compression attributes were passed along to the shading system so that when the skin was taught and tense it would become lighter and shinier. In compression it would become rougher and darker in the folds of the wrinkles. On top of that there was a secondary peeling/flaking skin which sat on top of the other deformers and was fixed in place at the base of the peeling skin of the underlying structure, but didn’t stretch with the main tentacle motion.

On the animation side, how did you manage so many arms and the fight with the Engineer?

Animating trilobites was down to the skill of our fantastic animation team led by Mike Cozens who hand animated each tentacle and the body of the creature to always feel like a continuously moving organic mass, and also solving the incredibly complex problem of making it fit with the engineer’s motion onset. Our camera department had to do a perfect matchmove of the engineer for which we used three reference cameras . This was further complicated by the onset lighting having erratically strobing banks of lights that traditional tracking software had a hard time with. Lee Bramwell’s camera team did a great job making sure the engineer sat correctly in 3D space to give the animators a target to work with.

What was your approach with the Proto-Alien that emerges from the Engineer?

Similar to the baby trilobite, the deacon was a real puppet built for the performance on set, so we started by replicating its build digitally. We quickly discovered that we needed to augment the model considerably for articulation of the muscles and joints to make it feel more like a natural, physical creature. Ridley wanted the secondary mouth animation to reference the action of a goblin shark, which can dislocate it’s jaw and launch it forward to catch its prey. We needed to redesign the whole mouth and lower jaw to give the structure to build in the mechanics of this action. For this we went back to reference Giger’s original work and added in his details, which our sculpting team led by Florian Fernandez designed.

Can you tell us more about the challenge of its particular skin?

The deacon’s skin is slightly pearlescent. We wrote a custom shader for the way the pearlescense reacts with the light. There is also a layer of blood, mucus and liquid all over the skin, which gave us a layered shading model to get the complexity of the material qualities of the skin. The lighting was a continuation of the strobing lighting and was artfully matched to the clean plates by leads Florian Schroeder and Adam King.

How did you use Deep Compositing on this show?

Deep compositing is now standard at Weta Digital, where we find it has numerous advantages. Its biggest use was probably in the engineer/trilobite fight where we had such a tight integration of digital tentacles and the practical engineer.

What was the biggest challenge on this project and how did you achieve it?

The diversity of the effects was the biggest challenge. Almost every shot was bespoke in one way or another. Every engineer shot was an escalation of the one before it, all the medpod shots were unique, and each Trilobite shot had it’s own tracking or animation design issues.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

Some of the reference footage we looked at for the medpod sequence kept me up at night!

What do you keep from this experience?

I have a world-class team to work with at Weta Digital who pulled out all the stops, and I think their enthusiasm really shows in the quality of the work. Working on such an iconic film with such a great collaboration with the studio, Ridley and Richard, really bought out the best in the VFX.

How long have you worked on this film?

We started the first test in Dec 2010, and completed the last final in March 2012.

How many shots have you done?

About 215.

What is your next project?

Joining the Weta team on THE HOBBIT.

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

This list could go on for a long time! Off the top of my head.

BLADE RUNNER – the dystopia of the city was immersive.

2001 – Trumbull’s slitscan effects are immense on a 70mm print.

BRAZIL – imaginative, bleak and hilarious at the same time.

WITHNAIL AND I – watched far too many times as a student, it never gets old.

and of course ALIEN!

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

– Weta Digital: Official website of Weta Digital.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2012

Great article! It all looked so good, they did a great job.

Wow. QUite informative.

Thanks Art of VFX.

Good work mate! We come a long way since riddick!

Eye-opening shots and interview. I had no idea many of those scenes had so much CGI.

Hi, and thanks for this awesome article.

I have a question,

the elephantine helmet wireframe looks high poly…

is this a result of some smoothing or sculpting output?

Or this is hand modeling?

Was a great movie loved every bit of it at the cinema!