With more than 16 years of experience in visual effects, John Bowers has worked on numerous projects, including Star Trek Beyond, Lovecraft Country, The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, and Monarch: Legacy of Monsters.

Joseph Servodio kicked off his career in visual effects with Godzilla: King of the Monsters in 2017. His subsequent projects include The Mandalorian, The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, and Dune: Part One.

What is your background and how did you get involved in this series?

Joseph Servodi (JS) // I’ve been working in visual effects for the last seven years. I was brought onto Ripley by Maricel Pagulayan, my longtime VFX mentor who also served as a VFX producer on this series, and actually gave me my first ever VFX production assistant job years ago on Godzilla: King of the Monsters.

John Bowers (JB) // I grew up in Wisconsin and studied math and Russian in college: my first job after moving to LA was teaching algebra and pre-algebra to 8th graders in the Los Angeles Unified School District. I’ve been in visual effects now for 16 years, primarily as a compositor and compositing supervisor. Ripley is my first show as VFX supervisor and I joined during post-production after a call from co-executive producer, Ben Rosenblatt, who I’ve known and worked with for over a decade.

How was the collaboration with the showrunner and directors?

JS // The unique thing about Ripley is that Steven Zaillian was the writer, director, and showrunner. So that created a much more streamlined and efficient workflow for visual effects because we really only had one step of creative approval and that was Steve.

JB // It’s unusual to have a single director for all episodes in a season of television, but that arrangement meant every shot truly had a constituency of one: the whole task was to find the image that he had in his mind, and to put that on the screen. Because he was always thinking of how the whole season held together––thinking of it as a single 8-hour movie––we always had to be sure any choices or changes we made would work in full context.

Steve’s complete ownership of Ripley also meant that, for a problematic shot, the best way to get to final was to be able to open up Nuke myself, with Steve over my shoulder, so we could iterate quickly, cut through any ambiguity about look and feel, and get to the picture in his head. Jason Tsang, the VFX supervisor for Assembly, was also embedded with production and was able to do the same thing. That ability to live-dial with Steve and collaborate directly was crucial, and we couldn’t have finished the show without it.

Were there any specific scenes or locations that posed unique challenges for the visual effects team?

JB // The big set piece at the heart of episode III: Sommerso, the fated boat trip off Sanremo, was by far the most technically challenging work in the show. It was also the crux of the story: everything in the first two episodes of Ripley builds to this moment, and all the events that unfold over the remaining five episodes happen because of it. The whole creative team knew from the start that the success or failure of the whole show as an artistic endeavor could sink or float based on the realism and artistry of this one scene. So those were the stakes, and that was the challenge set for us.

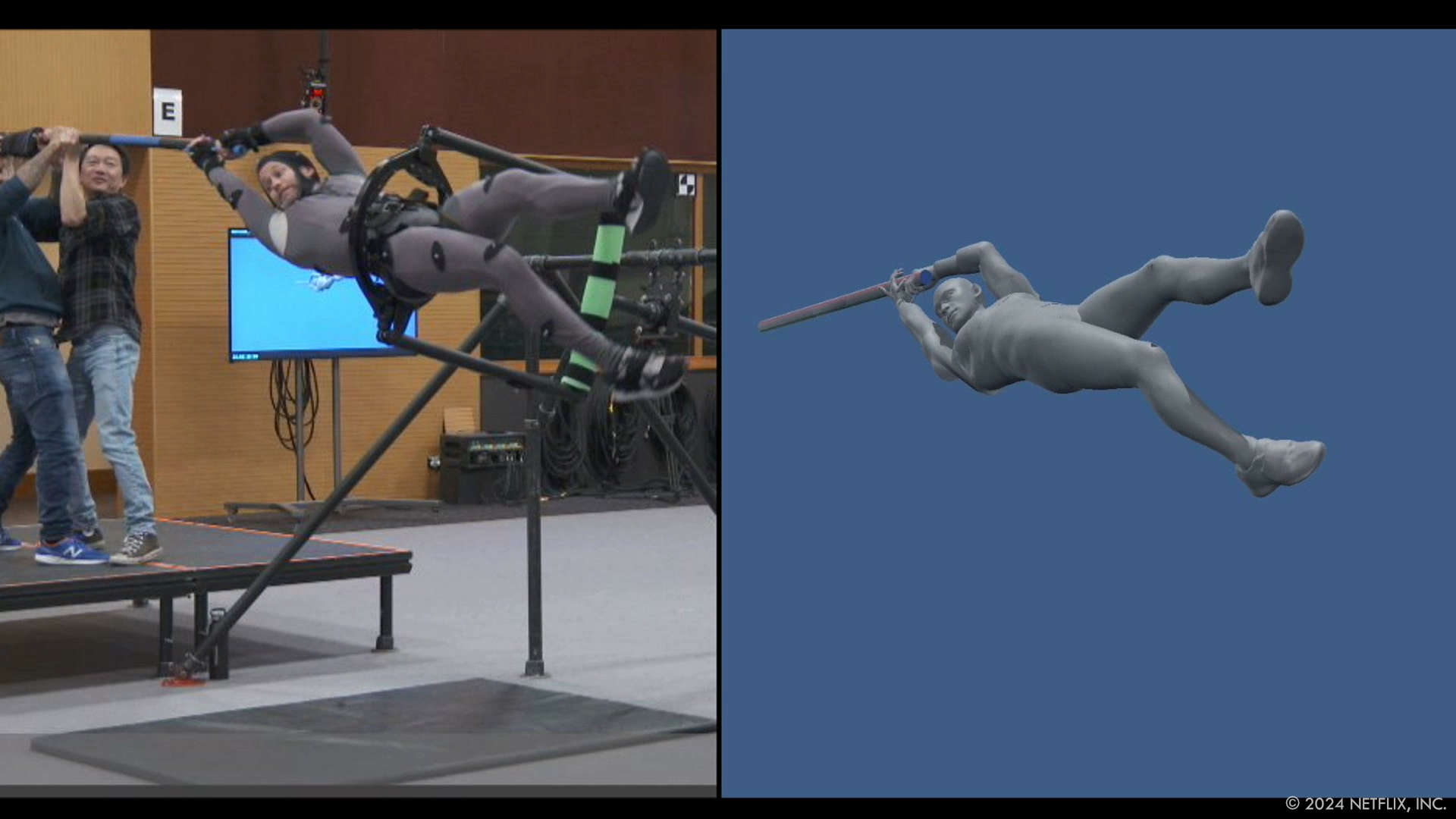

The level of preparation and planning for the boat scene––previs to guide principal photography, postvis to guide editorial, character scans, asset development––was unique among the episodes of Ripley. Once we reached shot production, the team at Weta FX had to design the progression of wounds and blood spatter throughout the murder sequence, integrate plate photography and practical elements into a full-CG environment, carefully art-direct ocean simulations & lighting, create an extensive particle effects both above and below the water, add fire elements (both practical and simulated), and animate hero digi-doubles with underwater hair and cloth simulations. The CG boat also needed to integrate seamlessly with the practical boat when used in part, to cut convincingly into the sequence when it was used in full, and to hold up to scrutiny even in extreme close-up.

The animated facial performance of Tom underwater was especially important and uniquely challenging, as the audience would be deeply familiar with Tom’s face and expressions by the third episode, and we needed to quickly convey his emotional state in a chaotic moment. Underwater. The animators at Weta, led by animation supervisor Jerry Kung, really nailed those moments.

To give an idea of how this specific scene stood apart in its demands: no other episode of Ripley included even one truly full-CG shot, but this 15-minute section of one episode wound up with twenty-six.

What role did pre-visualization play in planning and executing the invisible effects for “Ripley”?

JS // The boat scene in episode III: Sommerso was filmed in a fairly small swimming pool surrounded by green screen. It was a much smaller setup than you’d see with a large tank that was purpose-built for filming. Because of this, it was really important for our team to do extensive techvis to explore the best methodology for filming our most complex shots in such a contained, small environment. Later, we brought on postvis to fill in the gaps of what wasn’t possible to film for the boat sequence so the editors and Steve could cut together a complete, coherent sequence to hand off to Weta FX. Our techvis was done by Les Androïds Associés, and our postvis was led by Pepe Valencia of BARABOOM.

What is your role on set and how do you work with other departments?

JS // It’s important for visual effects to be on set to oversee the execution of any shots that require VFX in post-production. The team also needs to collect all onset data and references that will assist the visual effects artists in post. For Ripley, this included drone photogrammetry of coastal environments, lidar scans of Italian cities and buildings, as well as our sets, props, and vehicles, and full body character scanning of Andrew Scott, Johnny Flynn, Eliot Sumner, and a slew of background performers to create digital doubles.

How do invisible visual effects enhance the storytelling in “Ripley” compared to more obvious special effects?

JB // I’d like to think none of our effects are obvious! The whole point of “movie magic”––and the real genius of that metaphor––is that magic, when performed by a real magician, takes countless hours, focused practice, and genuine artistry to create a convincing illusion that appears effortless to the audience. Movie magic is the same.

Every single thing we put on the screen is only there to serve the story. There’s never a moment in Ripley when we want the audience to be dazzled by spectacle: for every one of our 2,000+ shots, we wanted the magic trick to work.

Can you describe some of the key locations used in “Ripley” and how visual effects were integrated into these settings?

JS // Tom Ripley travels constantly in this series. Every train station he visits––Naples, Rome, and Venice––is a CG environment. Interior locations such as Tom’s Rome and NYC apartments, Marge’s Atrani home, and the various hotels were shot using green screens outside the windows and unique DMPs were created for each location. Additionally, almost every exterior location in this show had some degree of period cleanup to do, whether it was removing a modern satellite dish, painting out unseemly graffiti, or removing a COVID mask on a passerby in the background.

JB // Don’t forget the ferry from Naples to Palermo and back in episodes 106 and 107! The artists at ReDefine did so many versions: “how does it feel if Tom is 10 feet above the water? What about 30 feet? Is this ferry traveling at 14 knots or 20? What if the swells on the water surface were four feet high? Two feet high? How dim can we take the sky while maintaining visual interest? How bright can we make the sky and have it still feel moonlit?” Those dozen or so shots were a real journey, and their supervisors Viral Thakkar and Matthieu Presti and were troupers throughout.

How did you choose the various vendors and split the work amongst them?

JS // We had seven great vendors on this series including Weta FX, Effetti Digitali Italiani, Assembly VFX, Powerhouse VFX, Crafty Apes, ReDefine, and Lightbender. Each vendor was brought on for a unique reason. For example, in episode III: Sommerso, Weta FX was brought on to tackle the boat sequence because their water work is truly incredible. Effetti Digitali Italiani was brought on for a chunk of the Italy-related work including the CG build of the Sanremo coastline because of their historical knowledge of the country and on-location support if the need ever arose to collect more reference or data.

What were the main challenges in ensuring that the visual effects remained invisible to the audience?

JB // Integration, integration, and integration. The moment that anybody in the audience is able to detect a dodgy falloff on a key, wobble in a roto edge, or a little slippage in a track, your cover is blown. You might think monochrome would be more forgiving, but the black-and-white presentation of the show, the pace of the editing, and the stillness of Robert Elswit’s camera work actually meant we had nowhere to hide, because the eye has plenty of time to travel around the frame. Movement and color give you opportunities to camouflage an edge; stillness and black-and-white actually demand even greater precision.

How did your team approach the seamless blending of practical and digital effects in various scenes?

JB // I like to say that every visual effects shot is custom-made by hand, and that was especially true here. In order to get our VFX shots to flow seamlessly with the rest of the show, we always had to be driven by reference, especially the non-VFX shots surrounding our work: observing carefully how focus should fall off in the lenses being used, how the lenses breathed during a focus rack, or how light should play across the surfaces of buildings.

How do you ensure that the visual effects maintain consistency across different episodes and locations?

JB // Having one director for all the episodes was our main protection against this, as well as having me in-person with him and with both editors, Josh Lee and Dave Rogers. I could review and give notes on isolated shots as they came in, but before we could put it in front of the director, we had to have a coherent sequence: just about every VFX review we did with Steve was really a sequence/context review, always driven on the Avid by our brilliant VFX editors Rolf Fleischmann and Garrett Lynn. Because Steve knew the whole show by heart, top to bottom, forwards and backwards, he was the one best-equipped to say “let’s compare this new shot to the sequence in this same location two episodes later,” and could also decide whether he wanted to be locked into continuity or to play it a little looser for story or compositional purposes.

Can you share an example of a scene where invisible effects were crucial to the narrative but remained unnoticed by viewers?

JB // Two major story points in episode VIII: Narcissus—our finale—were revised with just a few months left before the show came out. It all started with a note about the plausibility of Inspector Ravini not recognizing Tom when he sits for an interview as himself in Venice: in the original script, since Tom (as Dickie) has already met Ravini in Rome, he takes inspiration from Caravaggio’s paintings and decides that darkness will be his disguise, changing light bulbs and moving lamps around to shroud himself in shadows. But that didn’t quite play.

We weren’t able to reshoot with Andrew Scott, so the solution we came up with was to augment his appearance with a CG wig and full beard for that scene. Then, to prime the audience, we created insert shots leading up to the reveal of the wig: Tom entering a wig shop, him getting ready in a bedroom mirror, some close-ups of spirit gum and hair clippings. I saw a bit of chatter online about this scene, but every bit of it takes for granted that it was done practically, which speaks to the incredible work by the artists at Powerhouse to simulate and integrate that wig.

The other story change followed from that one: since Ravini would now meet with long-haired, bearded Tom at the palazzo, he couldn’t very well be the one in the scenes with Tom, Marge and Mr. Greenleaf the following day. And we couldn’t have Tom wear a wig in those scenes, because Marge would give him away. So a re-shoot was organized with Bokeem Woodbine—who played private detective Alvin McCarron in the first episode—and the team at Crafty Apes removed Ravini and comped McCarron into those two scenes.

That was all a big fun curveball for us—adding over a hundred shots to that episode—but totally invisible to the audience, and all in service of telling a more believable story.

How did the visual effects team collaborate with the directors and cinematographers to achieve the desired look?

JB // Every episode of Ripley was written and directed by Steven Zaillian, and every camera shot was framed by cinematographer Robert Elswit. Steve would often bring the picture editors into VFX reviews for their input and insights, but he always had the final say. Over time, you come to know what somebody likes and dislikes: Steve, to his credit, prized thoughtfulness and appreciated when we would take a big creative swing at something, even when I missed.

How do you balance the need for invisible effects with the practical constraints of shooting on location?

JB // This is a big one for our show. In fact, after Netflix posted a VFX breakdown reel online last month, the comment section filled with questions that were mostly different versions of one idea: why not just shoot this for real? Isn’t this yet another example of CGI run amok, ruining the visceral experience you’d get from filming everything practically?

The real answer to that objection is, of course, that a director’s creative vision sets the parameters for what needs to happen, and then our own creativity arises within those constraints. Steve wrote and envisioned a beat-for-beat retelling of the scene as described in Patricia Highsmith’s novel: a long and brutal sequence of Tom’s assault on Dickie, Tom’s burning of the anchor tether, his fall into the water, the uncontrolled circling of the unmanned boat, and the disposal of Dickie’s body at sea. The water and the sky would extend to the horizon with no trace of land, but the cinematography needed to echo the balanced compositions and steady camera work seen in the rest of the show, rather than bobbing wildly on the open ocean like a camera on a follow-boat would do.

The best way to achieve all that, and achieve the kind of consistency that would support the storytelling, was to discreetly deploy all the tools of modern visual effects: to shoot for real what could be shot for real under the dictates of the creative vision, then execute that vision to the highest possible standard.

Were there any unexpected technical or creative challenges encountered during the production?

JB // The black-and-white presentation of the show wasn’t exactly unexpected, since we knew from day one that Steve envisioned the series being shown in black and white. Even though we worked in full color, though, the constraint of black-and-white would arise more often than you might expect.

To take one small example: blood is red. When you see a red splotch flying off someone’s head, or smeared on their face or on the floor or on a bathtub, its redness does a lot of the work in communicating the blood-ness of it. But if you can’t rely on the visual cue of saturated red, you need to really key in on the specular highlights, the contrast of light and dark, the thickness and sheen that will tell your brain that you’re looking at a pool (or a smear or a trail) of wet blood.

One subtly tricky moment was the quick shot through the doorway of Tom hitting Freddie with the ashtray: getting that split-second spatter element to read as a separate thing from his brown hair––while still being big enough to be shocking but compact enough to feel grounded in reality––was a real magic trick.

Were there any memorable moments or scenes from the series that you found particularly rewarding or challenging to work on from a visual effects standpoint?

JB // I’ve already mentioned the wig work in episode 8, but the first shot leading into that scene was especially challenging. It was the closest thing to a full-CG shot outside of episode III: Sommerso, and the creative brief was totally open-ended: Tom walks into a wig shop at night.

We re-used a plate of Tom walking past the window of a glassware shop and into the door, but everything else about that shot was totally up for grabs. We went through so many rounds for set decoration, composition, lighting, depth of field…I tried, more than once, to talk Steve out of including the wig shop. But he was adamant that the audience needed it as a hint for what was to come, so that was one where we got multi-pass EXRs from the concept artist and I handled the final comp myself, in direct collaboration with Steve. He also asked Robert Elswit, the show’s cinematographer, to come in near the end to consult about how he would’ve framed and lit that shot had it been filmed practically. In the end, Steve was right: the shot works, it helps the story, and I think it turned out looking pretty nice. It was the very last creative final in the entire show.

Looking back on the project, what aspects of the visual effects are you most proud of?

JB // The underwater shots of Tom and Dickie turned out looking really beautiful. The camera work strikes the exact right balance of chaos and calm, the FX work is immersive and subtle, the animation is top-tier, and the compositing immaculate. I can’t take credit for that—that credit rightly belongs to Chris White, Francois Sugny and over 150 artists at Weta who lent their time and expertise to our show—but I’m so proud to have served as the bridge between New York and New Zealand, the midwife for those shots.

JS // I was blessed with a really special team on this show. Of course everyone was talented and great at their roles, but what set this team apart was that everyone was so genuinely proud and excited to be working on this project. That energy, to care about what you’re creating and be excited about it, really invigorates the entire work environment and can turn even the most stressful days into enjoyable ones. I think it’s truly the secret weapon to surviving any show.

How long have you worked on this show?

JS // I joined the series in June of 2021 and wrapped in March of 2024. So about 2 years and 9 months in total. Easily the longest production I’ve ever personally been a part of!

JB // I came on at the beginning of October last year, and actually wrapped a couple weeks after the rest of VFX production because we caught a small handful of stragglers in DI that I delivered directly to Company 3. So it was a total of six action-packed months for me.

What’s the VFX shots count?

JS // The total series has 2,146 visual effects shots. Episode III: Sommerso was our biggest episode with 400 shots. This episode included the boat sequence, which contained 227 shots. There were more shots in just that one 15-minute sequence than in most of the other entire episodes.

What is your next project?

JB // I’m working with VFX supervisor Mårten Larsson, VFX producer Jessica Smith, and showrunner James Gunn on season 2 of the Max Original series Peacemaker, which is shooting in Atlanta right now.

JS // I’m working on a new series for Amazon based on the Alafair Burke novel The Better Sister starring Elizabeth Banks and Jessica Biel, with showrunners Olivia Milch and Regina Corrado. So far it has been a great experience with a great team!

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Effetti Digitali Italiani: Dedicated page about Ripley on Effetti Digitali Italiani website.

ReDefine: Dedicated page about Ripley on ReDefine website.

Weta FX: Dedicated page about Ripley on Weta FX website.

Netflix: You can watch Ripley on Netflix.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2024