It all started at Storm Studios for Espen Nordahl, who began his visual effects journey there 20 years ago. After gaining experience at top-tier studios such as Image Engine, MPC, and Weta FX, he returned to Storm in 2013. Since then, he’s contributed to various productions like Invasion, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, The Last of Us, and Monarch: Legacy of Monsters.

How did you and Storm Studios get involved on this show?

We have worked with Matthew Butler on several projects in the past, and he reached out in early pre-production to see if this was a show that would fit our team.

How was the collaboration with the Russo Brothers and VFX Supervisor Matthew Butler?

It was great. We were given tons of autonomy and creative freedom to come up with ideas, designs and solutions and present them to Matthew and the brothers, and had a big say in which sequences and shots we worked on.

What are the sequences made by Storm Studios?

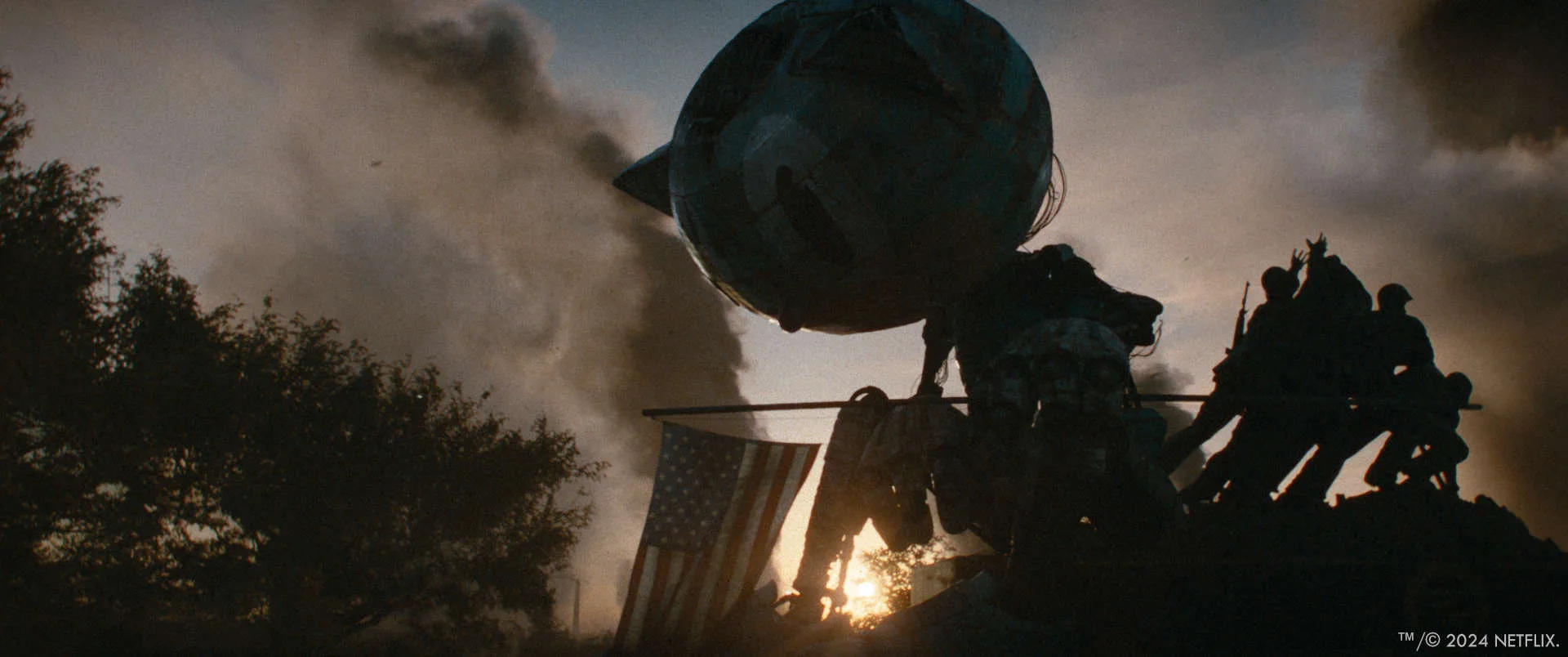

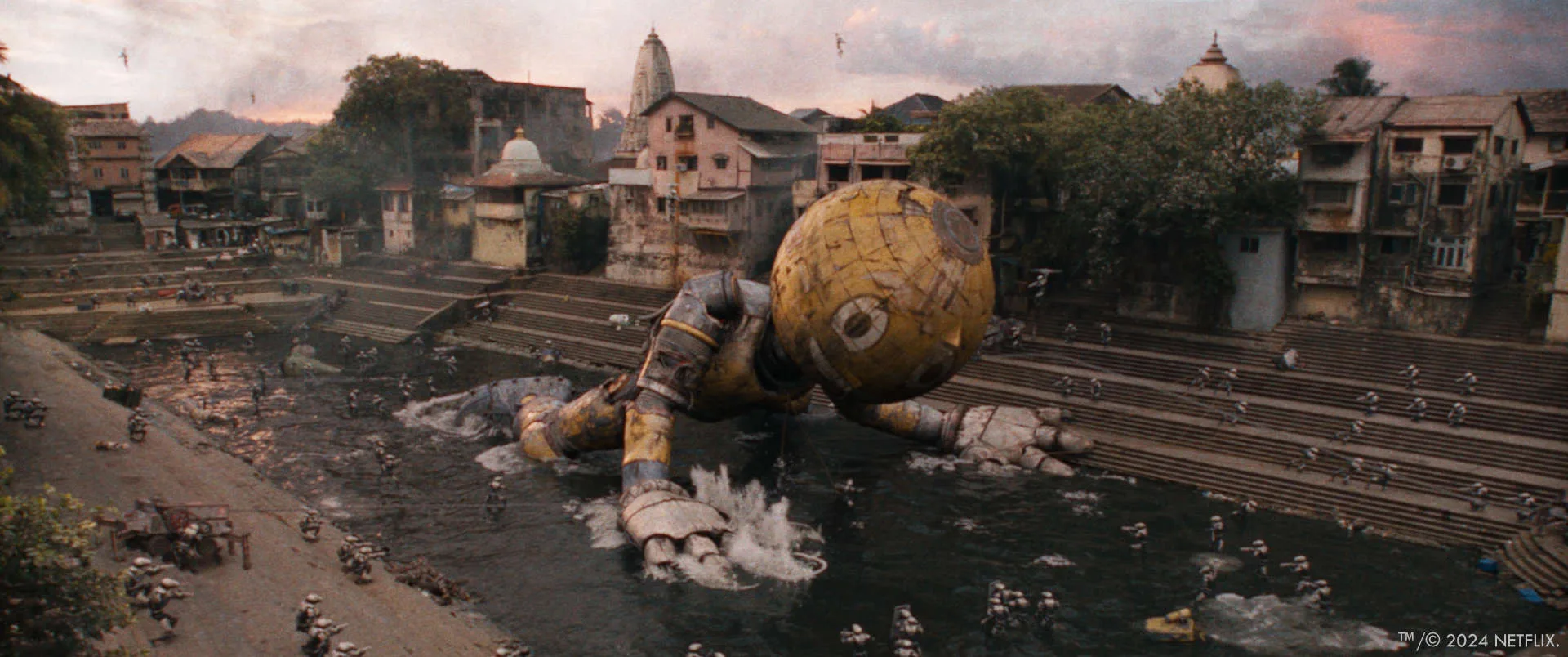

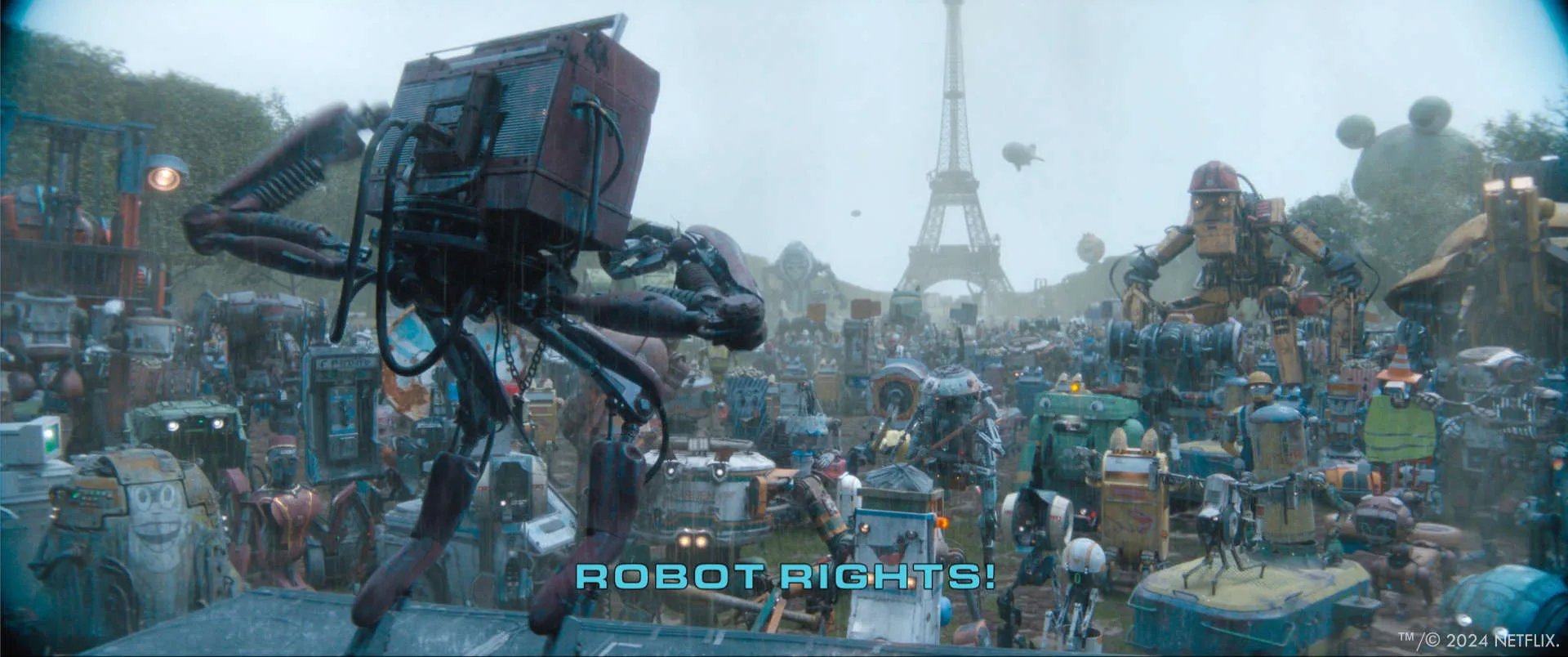

We did the prologue sequence, where the history of the robot war is explained. We also did a couple of VR sequences – one in a lake environment, one in a memory of Skate’s mother and one where Michelle talks to her brother in an Xmas memory, and a handful of one-off shots and shorter sequences with non hero bots.

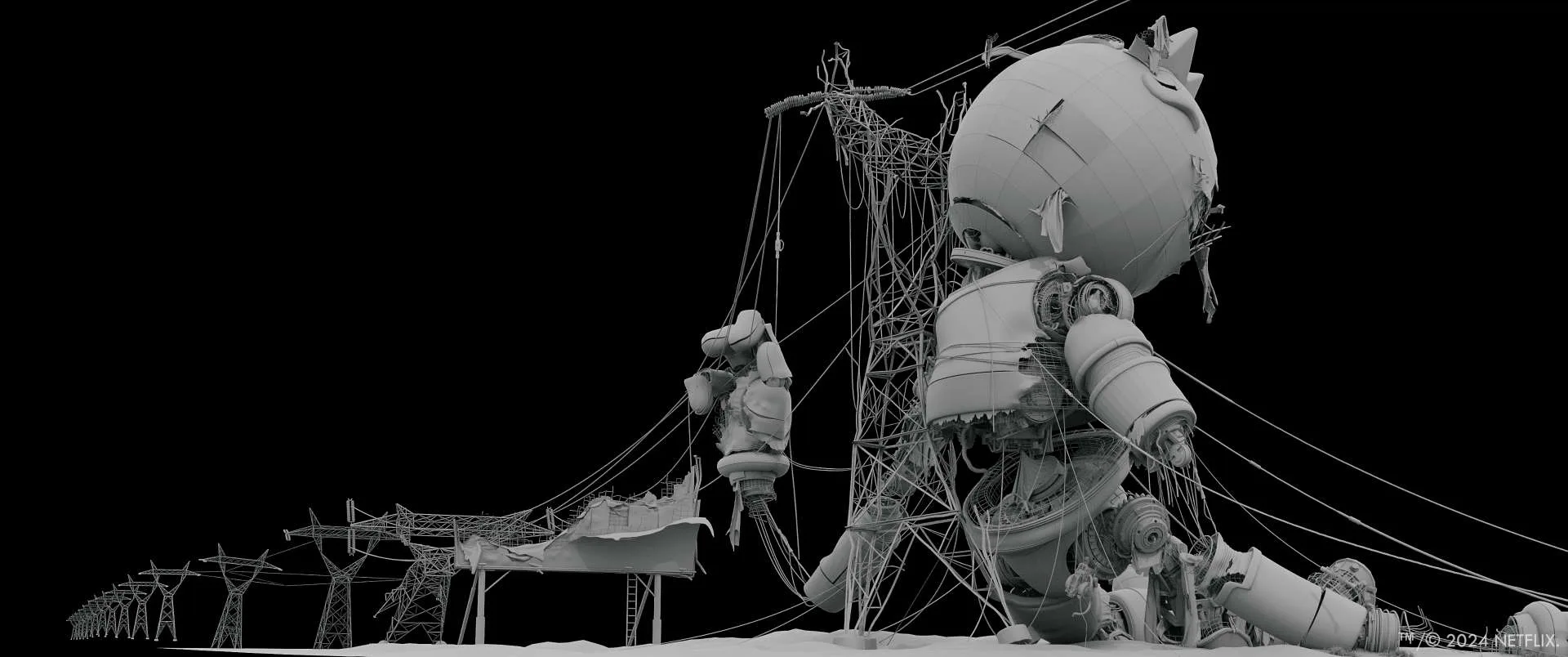

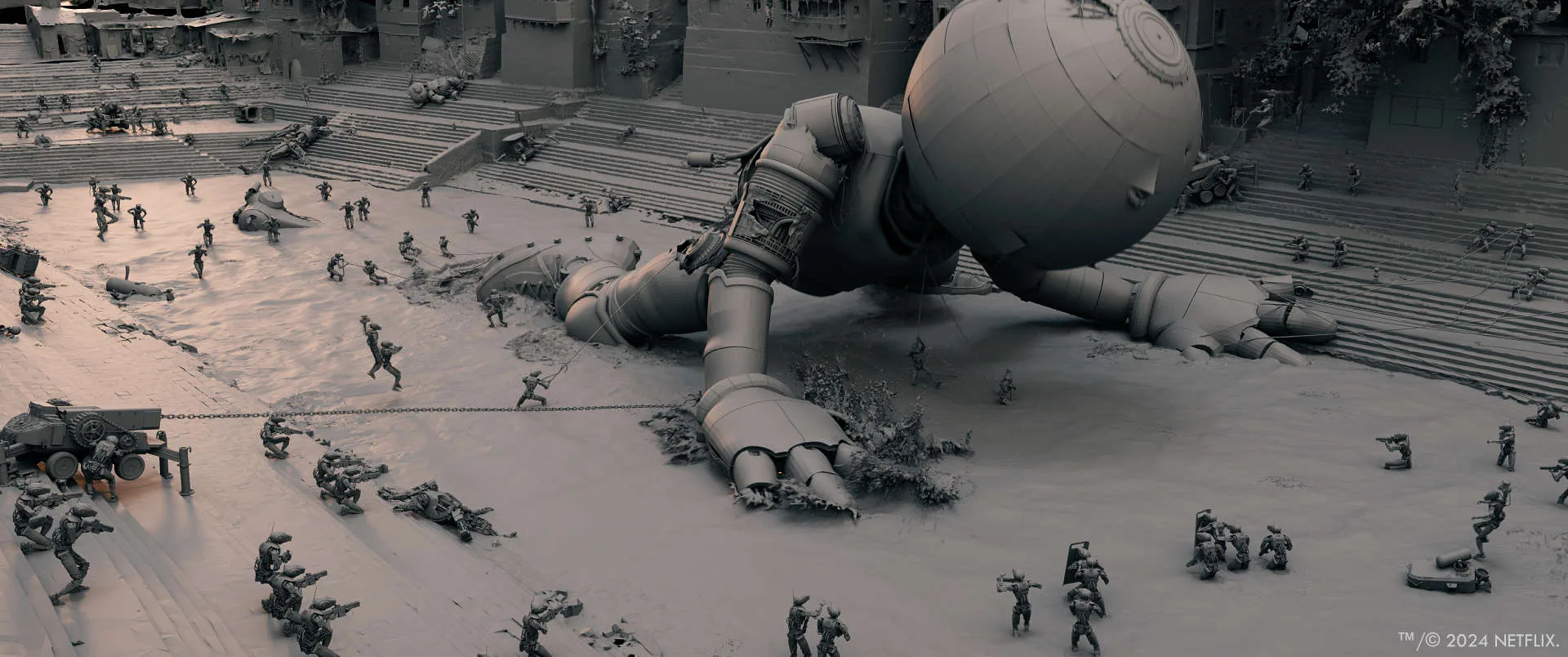

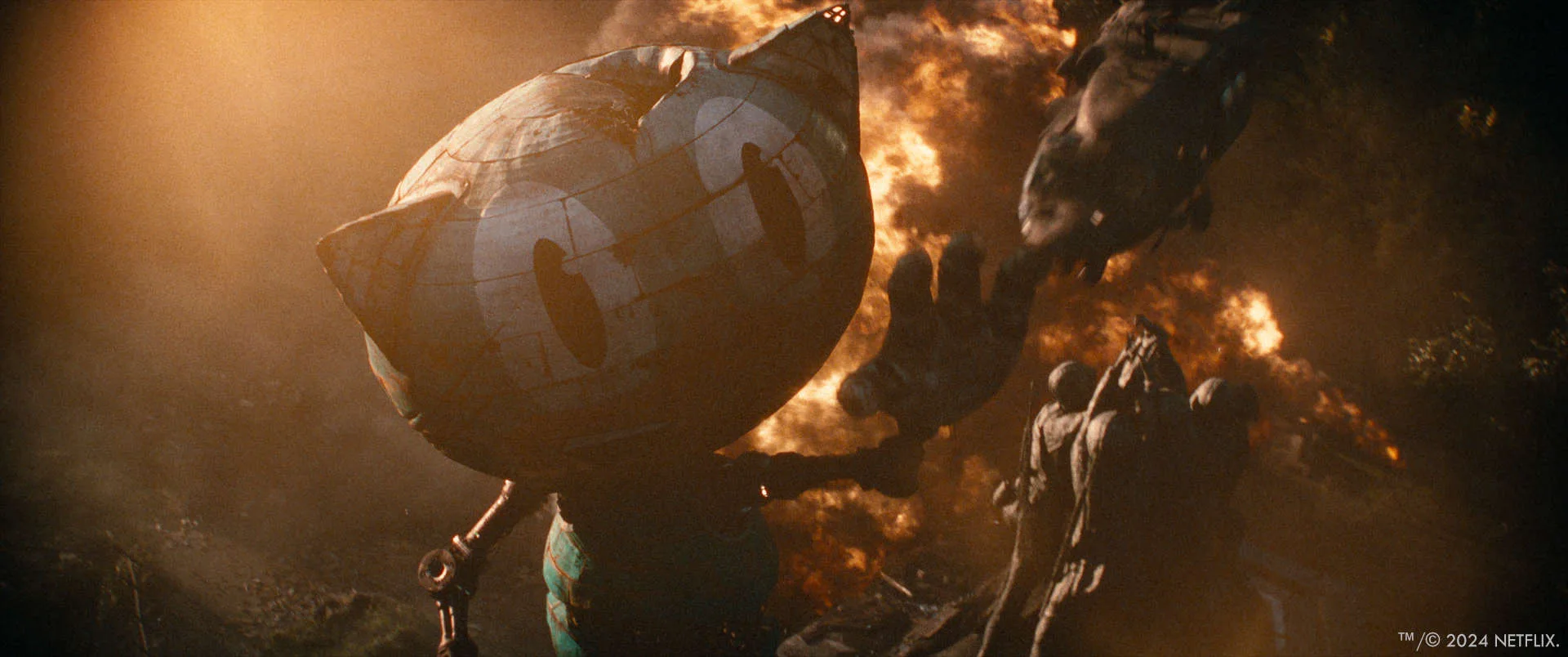

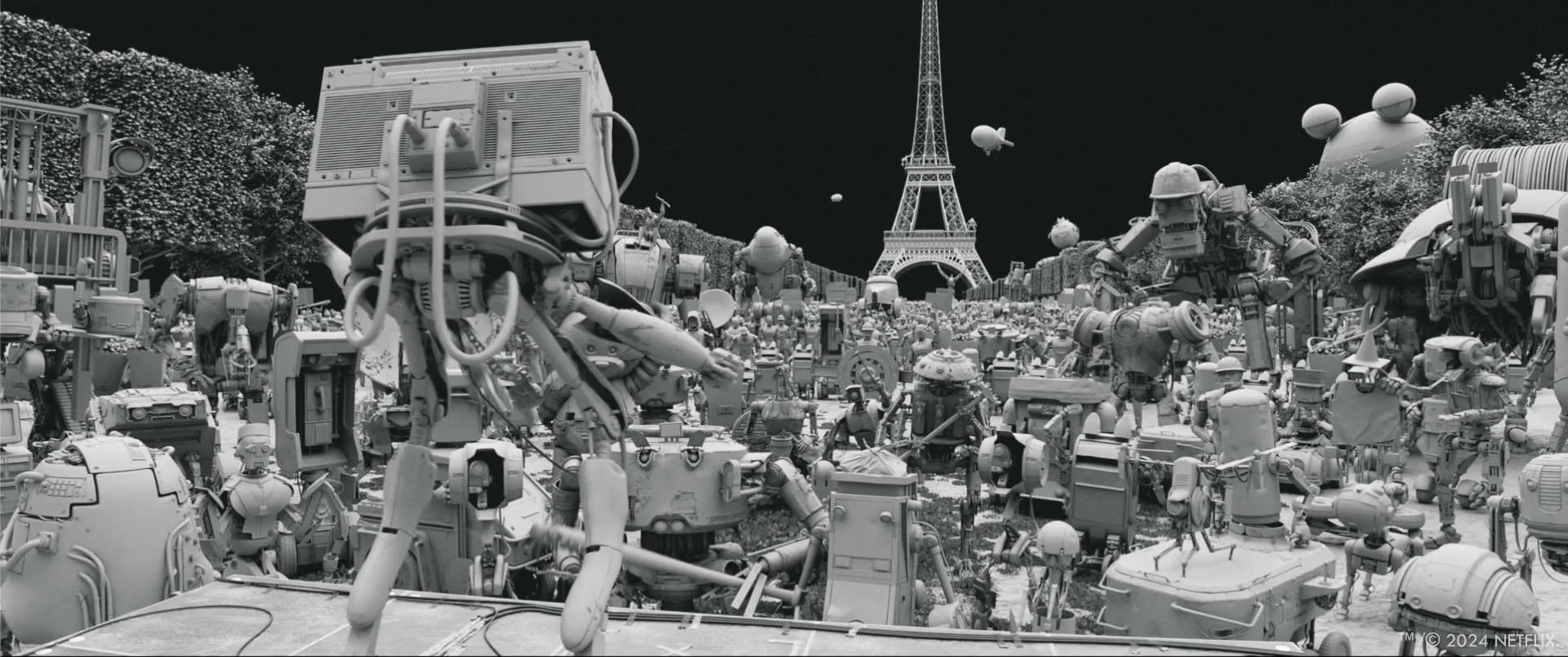

Each robot in the “robot war” sequence is unique. Can you walk us through your process of designing and animating these robots to ensure each felt distinct while still fitting within the same universe?

We tried to stay as faithful to the design language in Simon’s book as possible. That meant making the bots look like they were designed and built in the 90’s – and some times 80’s and 70’s depending on the bot. So we referenced a lot of old, analogue tech from that time. What worked best was when each bot was designed to do a specific job instead of a human – gardening, delivering mail, collecting trash etc.

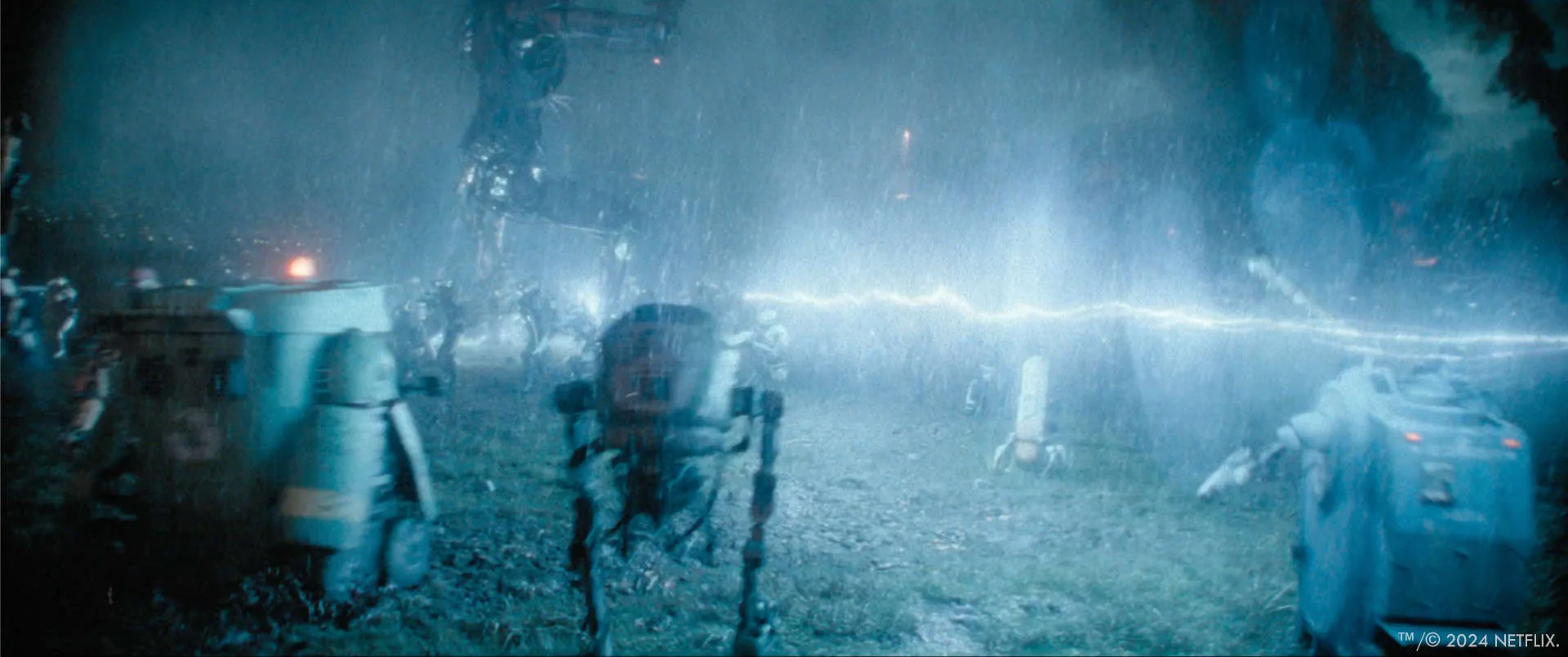

In terms of animation, what were the biggest challenges in giving the robots a sense of weight and physicality during the battle sequences, especially given the variety of shapes and sizes?

We spent a lot of time studying real robots and machines. One of the key factors to make them look old and clunky was to restrict their range of motion in their design. We tried to stay away from ball joints, and as often as possible using only one axis of rotation at the time.

Another helpful ingredient was to break motion up sequentially. So instead of for instance walking up to an object and reaching down to pick it up in one fluid, overlapping motion, we’d break it up into sub steps with breaks in between. We found the more we broke up a task into segments and the longer we’d make the pauses between each the more clunky and less human the motion would look.

Were there any specific references or inspirations you drew from for the movement and personality of the robots, or did you develop original techniques for this particular project?

The references we used the most were the Boston Dynamics videos – especially the older ones – as well as videos from robotics classes at several universities. We gravitated towards any reference where the motion felt old or clunky, as we wanted to avoid them looking too modern or fluid.

Mocap was great for blocking in scenes and trying out things, but they almost always came out too “human” and fluid, so once bot selection and layout was approved for a shot, we almost always used keyframe animation to take them to final.

How much creative freedom did you have in terms of designing the robots versus adhering to a specific vision from the director or other departments?

When we were brought on to the project the were some designs that were already done – either from the book itself, or by production. But most of the bots were designed by us. Every department was encouraged to pitch in with ideas, whether it was blocking out a model, doing some prototype animation or drawing concept art. We had a ton of fun coming up with hundreds of designs, around 50 of which were made into bots used in shots.

Given the wide range of unique robots in the film, how did you manage the technical aspects of creating so many different assets, ensuring each had its own functionality and animation, while maintaining consistency in the sequence?

Honestly, we didn’t use too many clever solutions here. Just plain old building a lot of robots from scratch. We did of course have texture variations to create a wider range of looks and regional variants – and the riggers encouraged modellers to stick to a set of joint designs so the rigs could stay modular.

The VR world in The Electric State plays an important role in the film. How did you approach the creation of this world, and what were some of the key challenges in making it feel immersive and integrated into the story?

When we started our VR shots there was already some work done by One Of Us on the buildup of VR the world when Michelle takes on the VR headset for the first time. We referenced this a ton in all our shots, staying as true to the visual language they had established as possible. The key being to have the artifacts feel as analogue as possible. So staying away from polygons, wireframes, pixels and particles, but instead using optical artifacts and analogue glitching seen in VHS, betacam, film etc.

The lake world sequence stands out visually. What were the main challenges in creating the water and surrounding environment, and how did you blend practical effects with digital elements to create that scene?

The brief for the lake world was that it needed to look photo real, but larger-than-life in design. Luckily we have some incredibly beautiful lakes here in Norway, so we travelled up to two of them – Lovatnet and Oldevatnet – gathering as much data as possible. Photogrammetry, drone footage, still photography as well as moving footage with the Alexa 35.

All of this was combined in Houdini, Maya and Nuke to create a custom environment from parts of the real location. The actors on set were standing in shallow water for interaction, but in the end it proved to be more work to integrate reflections of our environment into that than to re create it in Houdini. It did provide amazing reference of how the real ripples behave, and was great timing reference for rotomation.

Can you talk about the collaboration between the VFX team and the live-action crew during the creation of the virtual worlds, especially the lake scene? What was the process like for translating the director’s vision into a fully realized virtual environment?

We were given a ton of freedom on how to execute the lake scene. Since the lakes we wanted to shoot were here in Norway we were the ones shooting them, saving production the trip (and hike), and maintaining control over exactly what data to get and how to process it.

The bluescreen plates were of course shot by main unit. As was the Skate’s mom sequence. We received a huge amount of data from all three shoots – LIDAR, prop scans, reference photography and additional plates. It all proved incredibly helpful in creating the glitching effects.

Looking back on the project, what aspects of the visual effects are you most proud of?

I would say the scope. We are a small studio, and before Electric State we had never done this many high complexity shots on a single project, and it was amazing to see everyone in the team step up and deliver across the board. Everyone cared so much about this project, and it really shows.

How long have you worked on this show?

We worked on this show for a little more than two years.

What’s the VFX shots count?

We delivered around 100 final shots for the movie.

What is your next project?

I’m not allowed to talk about our current project unfortunately, but among our recent ones that just premiered is The Last of Us season 2 and Sinners, both of which we did a lot of very challenging and fun work on.

A big thanks for your time.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2025