In 2022, Stephen James explained the work made by DNEG on the film Bullet Train. He then went on to work on the HBO adaptation of the cult video game, The Last of Us.

Nick Marshall started his career in visual effects in 2009 at DNEG. He has worked on a number of projects including John Carter, Avengers: Age of Ultron, The Fate of the Furious and Blade Runner 2049.

Melaina Mace has more than 12 years of experience in visual effects. She has worked in many studios such as Whiskytree and MPC before joining DNEG in 2015. Her filmography includes many shows such as Star Trek Beyond, Wonder Woman, Dune and Foundation.

What is your background?

Stephen James (SJ): I was fortunate as my high school had a media arts program that let us make films, animations, wherever our inspiration led us. Vancouver had a lot of TV work at the time, but I wanted to work in film. I travelled to London with a demo reel in hand, and was hired at DNEG in 2005 as a junior compositor. I was very fortunate to learn from some incredible compositors, including Tristan Myles and Andy Lockley. I’ve been moving back and forth between Vancouver and London since then, but have been at DNEG Vancouver since it opened.

Nick Marshall (NM): I got into art in my teenage years which, combined with a love of film and technology, led me to pursue a career in VFX. I started working for DNEG in 2009 in London, and moved to Canada in 2015 when the Vancouver studio opened. Having worked the majority of my career as an Environments artist, I spent a few years as the Head of Department for Environments and Generalists, before moving back to show supervision for The Last of Us.

Melaina Mace (MM): I started out in VFX as a Digital Matte Painter and Environment Artist. I joined DNEG in 2015 where I have worked as a Lead Environment TD, Environment Generalist Supervisor and CG Supervisor.

How did you and DNEG get involved in this series?

SJ: I’m fortunate to have worked with Alex Wang on multiple projects over the years, at both Digital Domain and DNEG. Alex reached out to see about getting Nick Marshall and I involved on the show quite early on. I think our combined experience, myself in compositing and Nick in environments, made us the right fit for supervising the type of work that Alex was looking to place at DNEG.

NM: Alex and I had remained in touch over the years after working on a previous project together. A chance conversation around the time that he was seeking vendors for work on The Last of Us led to the idea of DNEG being brought on as one of the VFX partners. My familiarity with the games made it an opportunity that was too good to miss!

Have you played the original video games?

SJ: Yes, and they were inspiring even before we came to work on the show! Now, after working on the show and picking up the games again, all I can think to myself is ‘how on earth did they do this all in realtime?’

MM: Yes, I have played both Part I and Part II.

NM: Before embarking on this project I was familiar with the games – mostly as a big fan of the incredible design and concept artwork – but I had never played the games through. Once the idea of working on the HBO adaptation came up, I quickly borrowed a friend’s PS4 and immersed myself in the full experience!

How was the collaboration, the showrunners, the directors and VFX Supervisor Alex Wang?

NM: The collaboration on this show was fantastic; there was a fundamental love for the source material and a desire to do justice to the games that brought everyone together, and that passion could be felt at every level. Alex was insistent that our VFX team were as integrated into the process as possible, so we felt like creative partners from the moment the show began. Craig Mazin lent a contagious enthusiasm to every aspect of the show, and has been an incredible champion of visual effects. Having Neil Druckmann involved set the tone from the outset that this show would remain a faithful adaptation, and that got everybody excited.

SJ: Yes, it was a fantastic experience. Their passion for the material made us all want to make everything that much better. Delivering a project to this level of complexity, scale, and quality requires everyone working together to solve problems head on and we couldn’t have asked for better collaborators than Alex Wang and Craig Mazin.

What were their expectations and approach about the visual effects?

SJ: Considering the complexity and amount of visual effects throughout the series, Alex Wang and Craig Mazin showed a lot of restraint when it came to their approach. It’s not enough to make something look realistic if you aren’t engaged in the characters and story. Ground everything from the characters viewpoint, take a back seat to the story and characters so that when the visual effects do come to the forefront the viewer can totally believe in them.

NM: Everybody knew going into this show that the expectations would be very high. It went mostly unspoken, but it was incredibly important to do justice to the games and the phenomenal work that Naughty Dog carried out in crafting this world. We knew we needed to achieve a level of photorealism that would allow the visual effects to be completely seamless.

How did you organise the work with your VFX Producer and amongst the DNEG offices?

NM: The show was led out of our Vancouver studio, but a large shot count was contributed by the teams in our India studios. Nihal Freidel was brought on as the DFX Supervisor for the shots that were going through the India facilities. Each site retained key sequences and shots that they drove creatively, and the teams shared technical setups, reference from the games, and extensive location photography in order to keep things aligned aesthetically. VFX Producers, Jess Brown and Lauren Weidel, were key to the initial bidding and planning, and streamlining the final delivery of the hundreds of shots that DNEG was responsible for across our episodes.

What work was done by DNEG?

NM: DNEG was brought on primarily to work on the plethora of environments that were required for the show, but we also contributed some FX work for the Statehouse explosion, and lots of rain, digi-doubles and, of course, a Clicker! We were responsible for the Boston Quarantine Zone, as well as the Kansas City QZ and Jackson QZ. We also created many areas of destroyed Boston and Salt Lake City, including fully collapsed buildings, cratered streets, and the iconic leaning skyscrapers.

What was your approach to create the post-apocalyptic versions of Boston, Kansas City and Salt Lake City?

SJ: What I always loved about The Last of Us games was that each environment told many stories, and set the tone for the characters and the players along with them. What happened there on outbreak day? Who has passed through since then? How did mother nature reclaim it? We always started with this and encouraged the artists on our team to tell their own story. Depending on the sequence, we would dial between finding inspiration from the games, the real life locations, and the on-set production design.

NM: Our toolset consisted of three main techniques – build of full CG destroyed city buildings, build of non-destroyed buildings that we could use to simulate various destruction states, and extensive use of matte painting with camera projection mapping. Often we would mix all three methods in complex ways to achieve the best results.

Can you elaborate about the creation of these impressive environments?

NM: On a technical level, there was no huge secret to the way we approached the work. What was unique here was the attention to detail and the amount of time that was spent ensuring that nothing simply existed for the sake of it. Vegetation growth was heavier in areas where moisture and light would be prevalent, every exposed surface was treated carefully according to how the materials would naturally age and decay, interior details were designed according to the period and purpose of the building, and destruction had to respect how the real structures would react in these conditions. We didn’t cut any corners on design.

MM: Our Build department created more than 25 unique building assets for our Boston sequences to match buildings from the location shoot in Alberta, as well as Boston architecture. These assets all had full interior structures as well as dressing. Our environment and FX teams then ran destruction simulations on each, adding additional debris and set dressing, such as moving blinds and wires, for extra detail. We also created a number of generic destroyed buildings that could be re-used from multiple angles to fill out our background city. Once building destruction was creatively approved, our environments team designed procedural ivy set-ups and vegetation scatters for each hero building.

Beside the games, what kind of references and influences did you receive for the environments?

NM: We compiled extensive reference of real world locations to inform our decision making on everything from abandoned structures and communities, vehicles left exposed to the elements, as well as collapsed buildings and how degradation occurs under different conditions. In addition to our scheduled trips to photograph Boston, our artist teams also carried out field trips for gathering additional references. I think by the end of the show most people had a phone full of ivy photos!

MM: I ended up with an apartment full of ivy as well!

SJ: What you quickly realise is that inspiration and reference for weathering and overgrowth is all around you. Now I can’t sit on my back patio without staring at how the ivy grows, how some leaves are sun bleached or dead, and so on!

Where were the exterior sequences filmed?

MM: The series was filmed in Canada, around both Alberta and Calgary.

How did you manage the scale challenges for the buildings?

NM: We realised that the only way to relay the sense of scale in the city was to carefully mimic every tiny detail and imperfection that’s present in reality. Where possible, we would use human relatable scale cues, including furniture in the interiors revealed through the destroyed facades. Our build team, supervised by Bikas Panigrahi, did a great job of relentlessly detailing our assets, so that they were indistinguishable from the buildings in the plates.

Did you use procedural tools for the buildings’ creation and the vegetation?

NM: Most of the vegetation was procedural, created in Speedtree, and we used procedural scattering techniques in Houdini and Clarisse to populate the scenes. The ivy systems, created by Environment Supervisor, Adrien Lambert, were a complex procedural setup of multiple ivy genus that allowed for control of interconnecting living and dead growth. Procedural setups were also built for adding details like cables and rubble.

Which location was the most complicated to create?

NM: Each location presented different challenges for us, but the rooftop of the Bostonian Museum was the one that required the most elaborate and accurate build of a specific Boston district. We utilised photogrammetry and open source data in conjunction with our location photography to extensively build out downtown Boston, and used the city bombing as a justification to alter the skyline just enough to allow us to hit all the narrative points in the short sequence, including the final unobstructed view of the Statehouse.

What was the real size of the sets?

SJ: The on-set production design was quite impressive. They would often have hundreds of vehicles and huge sections of road dressed with weathering and overgrowth. An incredible amount of attention was given to making the world feel lived in, weathered, and overgrown. We were able to build on all of this great work when it came to the QZ, and various city environments.

MM: The Boston QZ set was one of the largest sets we were involved with – they built out a full city street with side streets on a backlot in Calgary. The set was built up to the first story of each building and we extended each building up to the third floor in CG. They also built the main gate of the QZ wall – we then extended it in CG and added watchtowers.

NM: Some sets were quite small, like the rooftop of the Bostonian Museum which was just a few meters across, while others were several real-scale city blocks in size.

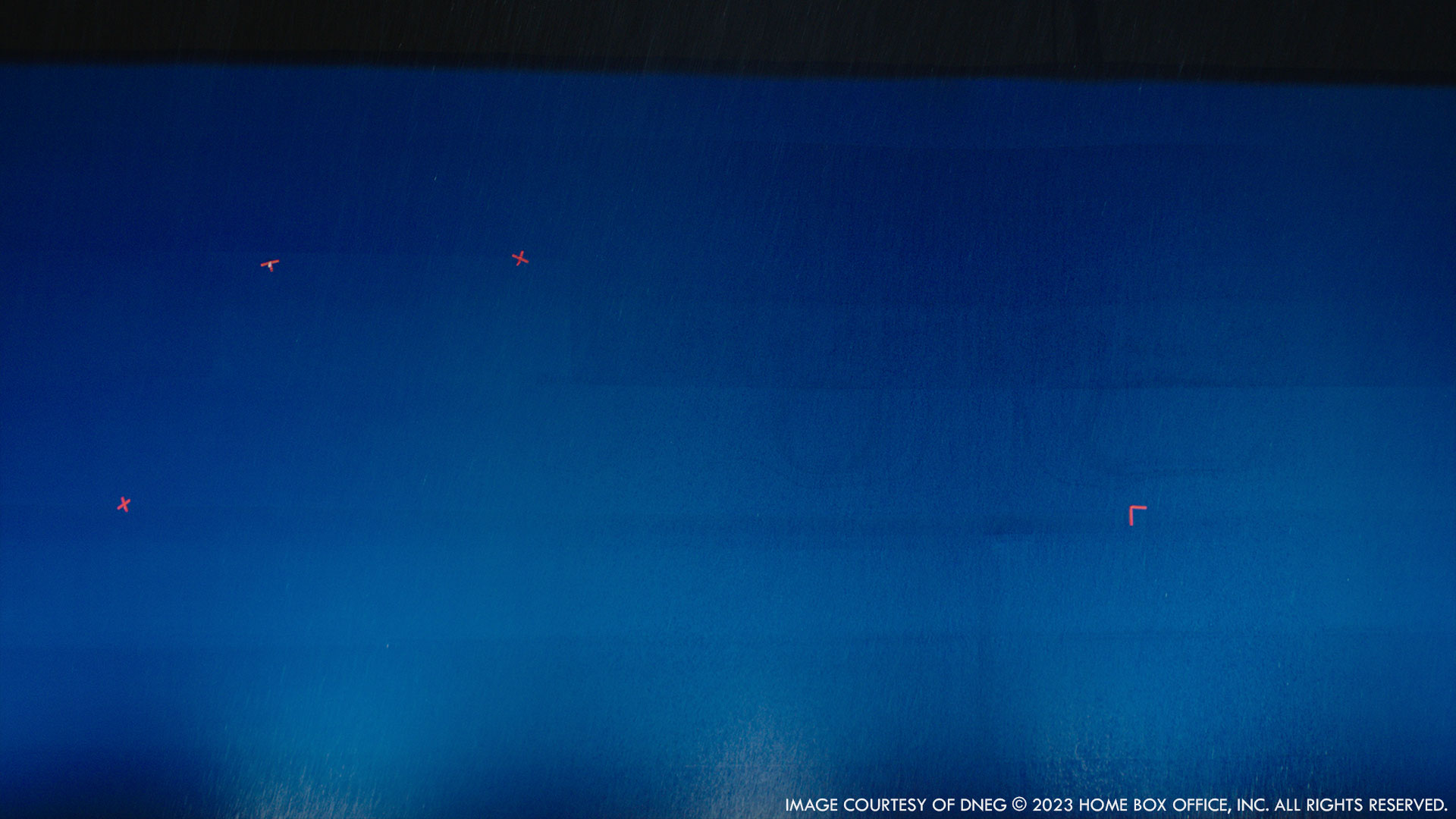

How did you handle the lighting challenges?

NM: For our big blue screen work where we didn’t have buildings in the plate to inform our lighting and depth cue, our lighting team, under the supervision of Casey Gorton, used high-res time lapse HDRIs to find a light condition that perfectly matched the set lighting. We then utilised our proprietary atmospheric tool, dnHorizon, to carefully match the atmospheric conditions to the chosen HDRI. Finally, we rendered a grey shaded reference pass of the set and used that as reference to grade the plates towards our CG to make everything consistent. By executing the work with a high degree of physical plausibility, we were able to inject a level of photorealism to our CG.

MM: We had some tricky lighting to match in some of the plates. A couple of the shots in the hair salon exterior and bombed street sequence in Episode 2 had multiple light sources on set. One of the glass buildings on location was reflecting a very bright sun keylight as well as caustics from the buildings around it. A set light was added to some of the shots that were filmed later in the day to maintain continuity, so we had to really study each shot and location in that sequence to replicate the lighting in CG. Our lighting lead, Natalia Valbuena, did a great job of setting up caustic lights to match the building lighting in the plate.

Which shot or sequence was the most challenging?

NM: Our most challenging single shot was probably the sweeping establisher of the leaning tower. That shot had a little bit of everything! Each building was meticulously detailed and damaged, and some of the plate integration really forced us to think outside the box. This shot is a good example of some of the very challenging compositing work on the show, executed masterfully by our comp team, supervised by Francesco Dell’Anna.

Is there something specific that gives you some really short nights?

NM: On this show I think it was simply the weight of expectation around the project. We owed it to the artists at Naughty Dog to do justice to the source material and we did not take that lightly.

MM: I actually had a nightmare about our render farm on this show! That’s never good.

What is your favourite shot or sequence?

SJ: It’s tough to pick one! I always come back to the ladder crossing and Statehouse view scene. This comes just after the encounter with Clickers in the museum and I love the sense of relief and awe you get as you step out into the open air high up above the city and look out to the Statehouse. You have a lot of time to take in some of the incredible work from our team.

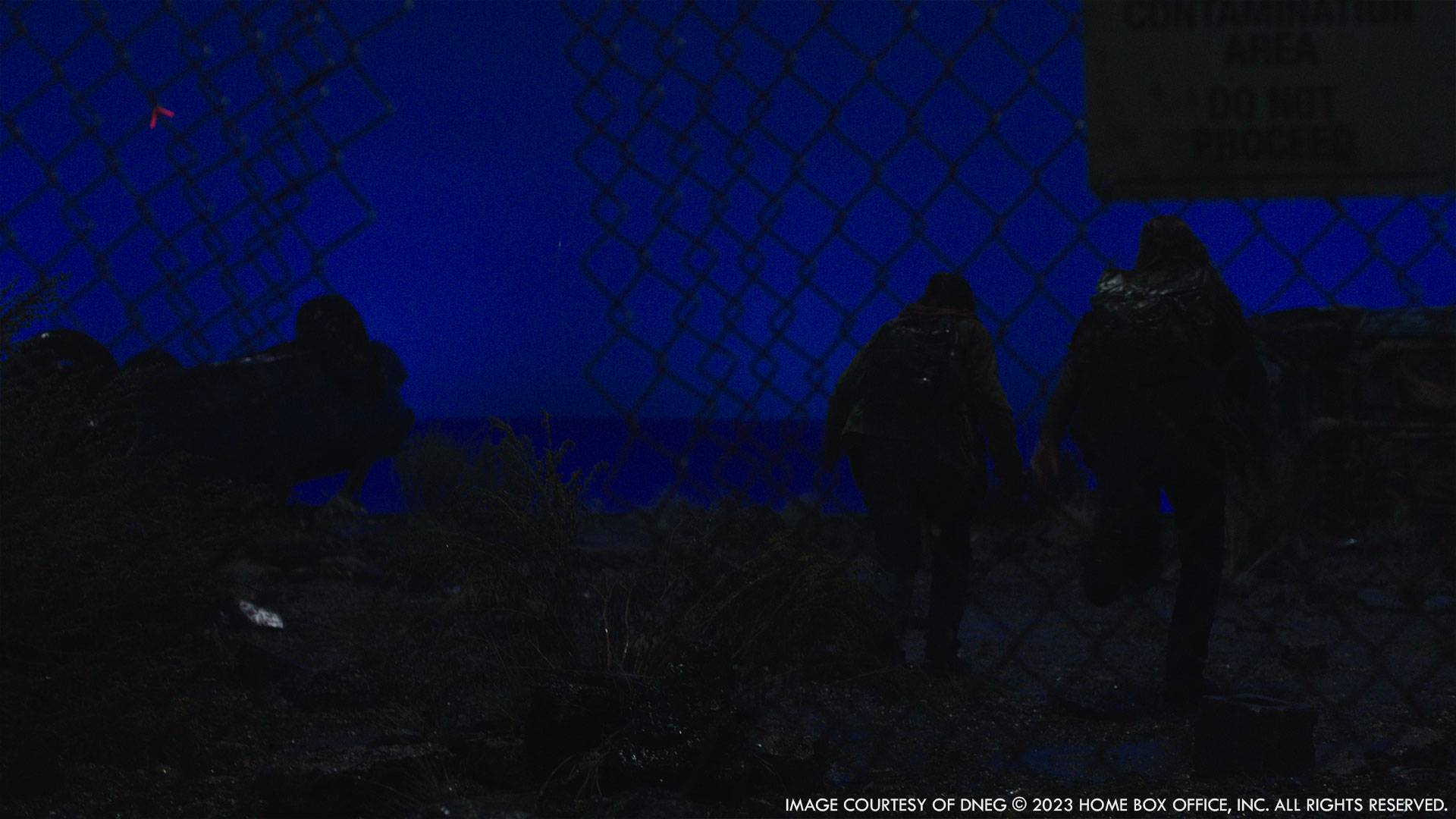

NM: I think I’m most proud of the closing shot of the pilot episode, with the characters heading out into the city at night. We carried out extensive research on cinematographers to find solutions to creatively light a night shot with no available natural light sources. Alex really trusted us to explore this and push the artistry for a very important moment in the show.

MM: I really like the exterior hair salon and bombed street sequence. I think the team did some really great work on those shots.

What is your best memory on this show?

SJ: Traveling to Boston and capturing data with the local Boston production team was definitely a highlight. I hope we did the Boston team justice in our total destruction of their city!

NM: The whole experience has been really positive, and the support the VFX teams received directly from Craig was very humbling. But if I had to pick a single moment, the initial walk-around the Boston QZ set was an incredible day. Being left alone to explore that huge set, and sit and sketch The Last Of Us world while surrounded by it was bizarre!

MM: Being able to go on set was definitely a highlight for me. Walking around some of the locations dressed with cars and overgrowth was very cool.

How long have you worked on this show?

NM: Around 18 months in total.

What’s the VFX shots count?

MM: Our total shot count across all episodes was 535 shots.

What was the size of your team?

MM: Across all sites over the course of the show we had upwards of 650 crew at DNEG.

What is your next project?

SJ: I will be supervising a sci-fi sequel.

NM: I will be collaborating with Stephen again on that sci-fi sequel after a brief break.

MM: I’m still wrapping up our final delivery. After that, I will probably go sit on a beach somewhere before jumping onto my next project!

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

SJ: Jurassic Park, The Elephant Man, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Dick Tracy.

NM: The Lord Of The Rings trilogy inspired me to seek a career in the VFX industry, but seeing Jurassic Park as a child was a long lasting influence. Blade Runner was very formative. I’ve always been very drawn to great storytelling over pure spectacle, so in recent years movies like The Social Network really blew me away.

MM: Blade Runner, Metropolis, Alien and The Matrix.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

DNEG: Dedicated page about The Last of Us on DNEG website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2023