Darren Poe has more than 20 years of experience in visual effects. He worked at Digital Domain, Weta Digital, Scanline VFX and then joined Double Negative in 2016. He has worked on many films such as FIGHT CLUB, STAR TREK, TRON: LEGACY and THE AVENGERS.

What is your background?

I started my career in visual effects back in 1996 at Digital Domain. At that time, I was an FX artist working on THE FIFTH ELEMENT and TITANIC. Prior to that, I had done some work in photography and graphic design, which is what I studied in college. As the projects progressed I found myself drawn more and more back into that world. I enjoyed the feeling of ‘finishing’ shots and putting the final touches on them before they were printed out to film. So I would start the shots doing FX, modeling, shading and eventually compositing them to final. In those days, pretty much everyone was a generalist in some way and the process was less compartmentalized than it is now.

How did you and Double Negative get involved on this show?

When I started at Double Negative, the show was already booked and in fact it wasn’t confirmed which project I would be working on initially. I was really happy to learn that I would be on THE MUMMY with Erik Nash supervising.

How was the collaboration with director Alex Kurtzman and VFX Supervisor Erik Nash?

I worked with Erik for many years back at Digital Domain – he was the visual effects director of photography on TITANIC and other shows, as well as the VFX supervisor on a number of projects I worked on. Erik brings such a wealth of experience and a strong photographic background to the table, as well as an even handed approach which focuses on the script and the story of the film. So I knew going in that it was going to be all about photographic realism and hitting the main beats, which was great.

What was their approaches and expectations about the visual effects?

I think that Alex in particular was concerned about over-using visual effects and he wanted to make sure that everything possible could be done practically (physically, on-set), grounded in reality and the VFX would be an extension of that. Of course, there are limitations as to what can be built physically but we always started with the photography. Alex wanted the effects work to stay as ‘invisible’ as possible in a VFX-heavy film of this scope. ‘Keep it subtle’ was one of the catchphrases on the show.

What are the sequences made by Double Negative?

We did a number of sequences with quite a range of visual effects work. Our scope of work included the Iraqi desert village battle and collapsing building/sinkhole, Ahmanet’s tomb and the mercury chamber, the desert C-130 sandstorm escape (up to the bird strike on the plane), Henry Jekyll’s transformations into Hyde, and the sandstorm in London, among other things.

How did you organize the work at Double Negative?

We had 4 teams working internally: ‘Team Tomb’, ‘Team Jekyll’, ‘Warzone’ and ‘Team Sandstorm’, which had their own leadership teams. Bernhard Kerschbaumer headed up the 3D departments overall and the 2D side was handled by Mike Brazelton.

Can you explain in detail about the creation of the village and the huge desert environment?

In fact, the central village itself was largely built as a physical set on location in Namibia. It was built in a horseshoe shape, where the action would start at one side and then progress around to the other end where a fully rigged collapsible building had been built by the SFX department. Beyond this physical courtyard, the village was extended out using a combination of CG and photogrammetry we captured at some locations in Morocco. The scenery in Namibia was absolutely stunning and you can see it in the other desert scenes in the film.

A drone comes to help the heroes. How did you created it and especially his missiles?

We modelled and built the drone in 3D; the missiles and trails were created and rendered in Houdini by our Warzone team, which was headed up by Rif Dagher. The missile impact explosions were done practically on-set by the pyro team – it was the last thing we shot on that set, for fear that the huge explosions would take out the whole thing!

How did you manage the FX simulations and animation on the drone attack sequence?

Much of the FX work here was about augmenting the practical SFX work done on-set. For example, the building that Nick and Vail are trapped on collapses during the missile strike. The building was built to full scale on set, and was rigged with hydraulics and cables to collapse in a controllable way. From there, we enhanced the shattering of the building with rigid body simulations and added dust and debris. Once Nick and Vail hit the ground, it got a bit more complex. They needed to slide down along the ground as if it was slanting towards a sinkhole which was growing outward from where the missile hit. Here, we replaced the ground with FX sand and dust simulations, all done in Houdini. The sinkhole itself was partially built on set, but we extended it outward with larger crumbling rigid sims and dust. We did full 3D rotomation of the actors, so that we could incorporate their interactions into the sim.

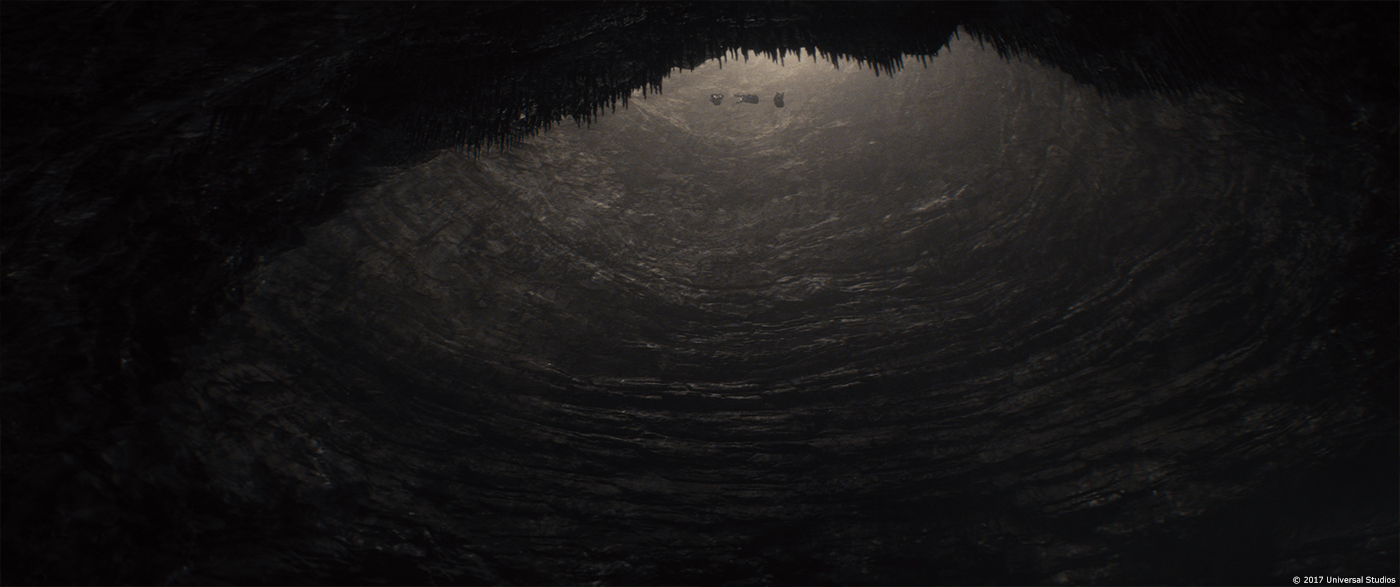

The heroes discover a huge tomb. How did you created this environment?

The entrance to the sinkhole (where the team rappels down into the cave) was built as a full size set on the Shepperton Studios backlot near London. Our work was to extend the cave down another 100 meters or so, which was done with a 3D model and re-projected matte paintings. We did some additional FX work of sand streaming down the sides, and other atmospherics. Once the team reaches the bottom, they find themselves in an antechamber with mercury dripping from the ceiling and collecting into channels on the floor, which flow into the main tomb chamber. The environments here were partial sets with CG extensions, including the chain mechanism which keeps the sarcophagus submerged. We created the dripping mercury, channels and also the mercury lake which contains the sarcophagus, using fluid simulations. This was especially tricky as liquid mercury has some very unusual properties – in particular it moves very quickly and doesn’t really adhere to anything. So we had to take some artistic license in order to do things like choreograph the mercury pouring away to reveal the sarcophagus.

What references and indications did you received to created this tomb?

Mostly, this was about looking at references of mercury and how it behaves. It turns out that there is a whole genre of internet videos dedicated to showing how mercury interacts with various substances, which was incredibly useful as a starting point. The production art department also built a miniature version of the tomb set, complete with the liquid mercury channels and lake. They filled it with mercury and experimented with it, shooting some video tests. So we were able to look at some great lighting and shading reference. We quickly found however, that the way mercury looks and behaves in real life does not necessarily translate into what worked in the film. In order to get a more ‘metallic’ look we opted for a more viscous behavior and a slightly less reflective surface. We added a lot of small details like particulates and cobwebs to give it more texture.

How did you created the scorpions in the tomb?

The creatures released when Ahmanet’s sarcophagus rises are actually camel spiders, which are rather large and frightening-looking relatives of scorpions. We modelled these in 3D to slightly larger than real-world scale, and created a number of variations in shape and texture. These were rigged to allow for a variety of base poses, and additional movements such as the breathing of the abdomen. We created animation cycles of the different poses, body variations, and walking/running speed. Our general approach was to create a particle simulation flowing along the surfaces of the tomb, to which we would then apply the spider animation cycles for rendering.

Any hero spiders, such as when they are close in frame or interacting with something, were done in 3D animation by our Animation supervisor Sebastian Weber and his team. For the look of the spiders, we had some on-set reference to match to: they had brought in some spider wranglers who put various spiders on the actors so that they could be photographed in different lighting conditions. Surely a pleasant experience for all involved!

Later in the movie, The Mummy brought a sandstorm to London. How did you approach this FX?

The Sandstorm started with a few ‘rules’ which were the basis of our approach. One of these was the idea that Ahmanet’s power is specifically to turn anything that’s glass into sand, and then be able to direct its movement at will. In fact, the original storyboards and design for the sequence had a whole series of shots showing the progression of how small individual glass items would shatter into sand and then collect together in an ever-growing wall of sand. Other design ‘rules’ were that the glass would shatter in larger pieces which would then subdivide down further and keep re-shattering until they reached particle size, and also transition from a glass color to a more sandy tone over time. With all this in mind we knew that a procedural animation approach in Houdini would give us the most freedom to achieve the result, but even more importantly, to be able to tweak it and change the ‘rules’ without going back to square one. Our FX supervisor Daniel Jenkins did some great work on the shading of the volumes which really helped us dial in the look.

How did you art directed the animation of the sandstorm?

Despite the fact that the sandstorm itself is a bit of a fantastical idea, the overall approach to the film’s VFX work is grounded in reality and physics. So rather than stylize the animation of the sand wall, we started with normal gravity and forces and let the timings of the window bursts and the volume of the sand drive the animation. Once we were happy with the general movement we would time-shift the overall sim as needed. Everything was composited together using deep data, so we had a lot of flexibility to tweak the individual layers later.

The face of The Mummy appears inside the sandstorm. Can you tell us more about its creation?

The idea of having Ahmanet’s face appear in the sand was something that came along later in the production, after we had already blocked out the animation and timings of the main sandstorm wall. To add the face, we started with a 3D model of Ahmanet and rigged it with blend shapes to allow control of her facial expressions. Once we had the animation and movement of the face, we used that to drive FX simulations of the sand and dust pouring off of the face which were then combined with the main sandstorm wall and rendered together. We did a few different types of sims and renders – experimenting with varying levels of clarity and visibility of the face, which we could then mix and match between in order to give Alex some options.

How did you recreated London for the interaction with the sandstorm?

For the most part, it was not necessary to recreate London for the sandstorm sequence. It was mainly shot in-camera (on location in the streets of London), and the nature of the effect was such that it did not require full building destruction. We did have a few shots which were entirely CG environments, which we built using reference photography and textures we captured on location during the London shoot. We also re-purposed a few highrise buildings and landmarks for shot composition reasons.

What was the main challenge on this show and how did you achieve it?

It’s hard to narrow it down to one main challenge, as our work spanned quite a range from environments, to creature animation, to heavy FX, and more. Each problem required its own unique approach. In terms of shot complexity, the London Sandstorm shots were quite involved. There are many additional effects simulations layered in there, debris and vehicles flying around, CG character animation and digital doubles, lots of background details and bits and pieces that needed to interact with each other. The amount of data generated to create the elements for these shots was massive.

Was there a shot or a sequence that prevented you from sleep?

Probably the most fear-inducing aspect was the sheer render time and CPU power needed to crunch through the heavy volumetric sims and renders. We did a lot of work to optimize, but semi transparent volumes are always tough.

What is your best memory on this show?

There were a lot of great moments. One standout for me has to be the shoot in Namibia. It was amazing to see all of that come together, with all of the incredible set work, stunts, special effects, vehicles, multiple units shooting… all out there in a remote and really spectacular environment.

How long have you worked on this show?

Start to finish, I was on THE MUMMY for almost exactly 1 year.

What is your VFX shots count?

Our shot count landed somewhere in the low 300s.

What was the size of your team?

It fluctuated but at its peak, I would say there were perhaps 100-150 people working on the show at any given time.

What is your next project?

My next project is to take some time, relax and enjoy the summer with friends and family!

What are the four movies that gave you the passion for cinema?

It would be hard to narrow it down to 4 movies specifically. What initially inspired me (and still does) are the films which made early use of visual effects, back in the days before technology became so ingrained in the process. It was all about the sleight of hand, there were no rules and there was no software to guide what could and couldn’t be done. The limitations of the medium necessitated so much creativity on the part of the artists.

A big thanks for your time.

// WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Double Negative: Dedicated page about THE MUMMY on Double Negative website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2017