In 2021, Matt Aitken explained to us the work done by Weta FX on Eternals. He’s back today to talk to us about Transformers: Rise of the Beasts.

With over 28 years of experience in visual effects, Mike Perry has an impressive filmography. He has notably worked on films like Contact, the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Avatar and The Hobbit trilogy.

Kevin Estey has worked in visual effects and animation for over 20 years. He has worked on films such as The Adventures of Tintin, Rampage, Avengers: Infinity War and Avatar: The Way of Water.

How did you and Weta FX get involved on this show?

Matt Aitken: Weta FX’s opportunity to get involved with Transformers: Rise of the Beasts came up quite late in the movie’s production schedule – the production was looking for a facility to work alongside MPC, who was the main vendor on the show. We came on board in August 2022, after principal photography had wrapped. We did get the opportunity to go on set in November 2022 for a week of additional photography on the Paramount backlot.

How did it feel to enter this iconic universe?

Kevin Estey: As a child, I was a fan of the Saturday morning Transformers cartoon and I had a fair few Transformers toys including Optimus Prime, Bumblebee, Soundwave, The Constructicons, and The Dinobots. I was a fan of the first Transformers film, and I still think it’s one of the more enjoyable popcorn flicks of its time. Needless to say, despite having lost touch with the franchise in recent years, the kid (and adult) in me was absolutely thrilled to get to be a part of this universe.

Mike Perry: Having been involved with visual effects for many years, it was incredibly exciting to get the chance to work on a film in the iconic Transformers universe, but also a little intimidating to take on the responsibility of living up to that legacy. The prior six films have continually planted flags in the visual effects landscape. Those films have always pushed the boundaries of what’s possible in many different aspects of effects creation, from CG character creation, integration, and augmentation of practical effects to huge set pieces, CG effects, and environments, and of course the signature character transformations.

How was the collaboration with the Director Steven Caple Jr. and VFX Supervisor Gary Brozenich?

Matt Aitken: Fantastic. Steven approached the work like the seasoned pro of VFX tentpole movies that he is, with a very clear idea of what he was after. Our story and animation review meetings with him were hugely enjoyable. Gary is incredibly experienced in all aspects of visual effects production, from shot design through character animation to FX, lighting, and shot finishing, so it was great being able to benefit from that wealth of knowledge. Gary was a great collaborator and we always felt like we were working as one with the production VFX team.

What was their approach about the visual effects?

Matt Aitken: We agreed with the filmmakers that on a show like this, getting the animation right was the most important thing. Because of this, we allocated the majority of Weta FX’s post schedule to animation, leaving FX, lighting, and comp to the final few weeks on the show.

How did you organize the work your VFX Producer?

Matt Aitken: The Weta FX production team did a fantastic job scheduling the project. They managed to schedule tens of thousands of individual tasks, spread across many hundreds of visual effects artists into the production window on the show. That enabled us to finish the show to Weta FX’s customary high standard of quality.

What are the sequences made by Weta FX?

Matt Aitken: Weta FX completed the opening sequence on the Maximal’s home planet, and the third act battle set in a volcano crater.

Can you elaborate about the design and creation of the Maximals?

Matt Aitken: By the time we joined the production, MPC had done a lot of work on the Maximals and we were able to inherit that via asset migration.

How did you use Weta FX’s experience with apes for Apelinq and Optimus Primal?

Kevin Estey: Having an extensive history of working with primates of all shapes and sizes, from King Kong to The Jungle Book, the Planet of the Apes trilogy, and The Umbrella Academy, Weta is the perfect place to bring giant robotic apes to life. The principals are the same but the mechanics, quite literally, of a robotic ape are much trickier. Gorillas, which Apelinq and Primal most closely resemble in physical stature, are bulky but very agile and flexible. One main challenge about robotic creatures is that flexibility is tricky, particularly due to the rigidity of their surfaces.

The most challenging aspects of these two primate characters were their shoulders and their faces. Their shoulders are the most prominent feature of their bodies and are visible in most shots, whether they are talking, reaching, running, swinging, or fighting. Because the shoulders were formed from single rigid metallic domes, there was no room for faking malleability. As a result, we had to essentially disconnect them from the arms and neck to manipulate them appropriately, given each type of action. We had to pay particular attention to them in every shot and treat each shot as a bespoke situation so the shoulders would appear to behave in conjunction with the character’s action. In many situations, this was a cheat to give the impression of them being “fleshy” when in fact they were largely disconnected from the surrounding appendages.

Likewise, Apelinq and Primal’s faces needed to emote in ways that were at times extreme, and at others emotionally subtle – many of these moments were in very featured close-ups, including a scene that is arguably one of the film’s most emotionally powerful moments. Weta has some of the most talented facial animators in the world, so there was no doubt in my mind we could achieve that level of performance, but the challenge was that we almost always work with fleshy faces. In this instance, we had to treat hard surfaces like flesh. As a result, we leaned heavily on our existing FACs pipeline and used our GENMAN human face as an underlying driver for the rigid primate faces. Imagine a human face, morphed to fit within the inner envelope of a giant robot ape’s face, painted a dark metallic colour (to help hide it), then covered in hundreds of individual pieces that form the exterior face of Apelinq and Primal. And believe me, when you catch this morphed human face without a rigid exterior, you may have trouble sleeping for a few days.

Regardless of the seeming nightmare within, this method proved very successful for utilising our knowledge and experience with facial animation to create incredibly emotive performances, with very subtle and believable nuance not generally seen in Transformer films. The issues that arose were the large number of intersections with the hundreds of rigid face pieces, due to the “flesh-driver” face beneath not obeying any sense of collision with the rigid pieces upon it. The solution to this ended up being a final clean-up pass that our facial animation team undertook, which entailed individually manipulating the face pieces, referred to as an elaborate game of Jenga. The results speak for themselves, as the opening sequence featuring Apelinq and Primal is as emotionally engaging as any pivotal scene with the most believable flesh-based characters in film.

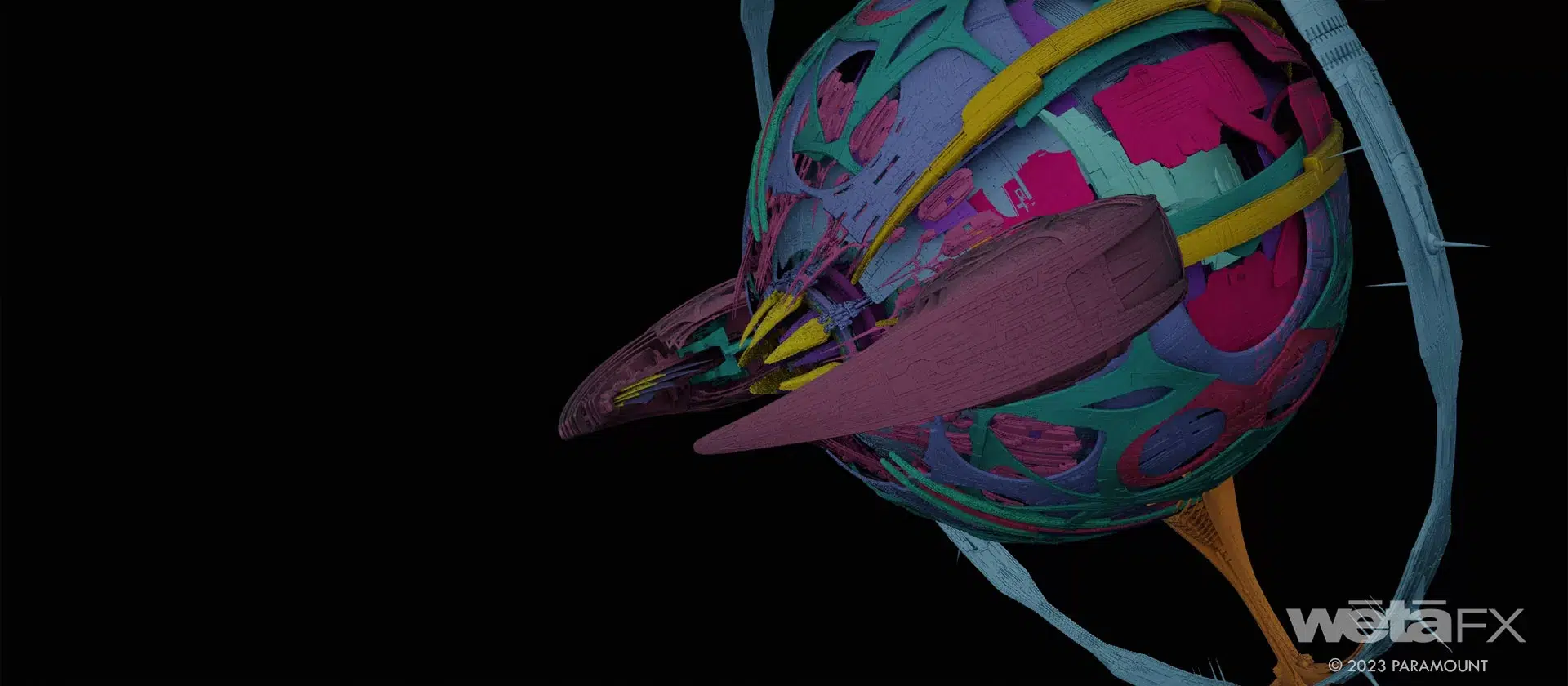

Can you elaborate about their characters’ various transformations?

Kevin Estey: Transformations, as we were told by artists who have previously worked on the franchise, are some of the hardest visual effects to create. They were not wrong. Every transformation you see is bespoke and unique. There is no blueprint, so there is very little that can be planned for. What we learned very quickly is that in order to make a successful transformation, the only guideline is that it needs to look cool. What may look cool at one angle, might not look cool at another, so our characters and their ability to transform needed to be as versatile and flexible as possible.

To do this on each Transformer animation puppet, we opened up full control of every panel, piston, screw, spring, and so forth, and made every single piece of the character fully modular in terms of potion, scale, and visibility. We further developed a methodology, called Mesh Tools, to cut up any piece of our characters on the fly beyond what existed in the puppet model. We essentially could do anything we could imagine, with zero limitations, which is a rare position of freedom for an animator using an animation puppet. An incredible amount of trust was given to us to simply not break the characters. This meant a lot, as one thing everyone in the industry knows is that animators are very good at breaking things.

We made a point of incorporating key aspects of the first generation (G1) Transformer toys’ actual transformations into as many of the onscreen transformations as we could, both as a way of driving the fundamental movements of the transformation, and to give the fans, including ourselves, a feeling of tangibility and nostalgia. Being able to show that Prime’s arms actually fit into his chassis at a 90-degree angle like the toy and that his head flips back into the hood, or that Bumblebee’s feet are formed from the rear of the Camaro with a simple 90- degree rotation, or that Primal’s legs rotate 180 degrees when he goes from Beast to Robot… it all helps give a feeling that the transformations are actually possible. It also fulfills that sense of childhood wonder we all had when playing with the toys imagining them all in action, knowing that the arms are hidden here, and the head is tucked away there.

The transformations are still largely a demonstration of sleight of hand. Many pieces have to disappear, reappear, fit into, or emerge from parts that are the wrong shape or size, all the while believably turning one complete puppet into another entirely (i.e. robot into truck). Many times, they don’t have the same volume, or in the case of Bumblebee, even the same type of wheels. One great example is Optimus Prime’s robot puppet, which when roughly folded into the shape of a Semi Truck is only 25% the volume of the actual Optimus Prime Semi Truck. So there’s a lot of trickery to get this change in volume to happen believably on screen.

What kind of references did you receive for the animations?

Kevin Estey: We had original Transformer toys in house as our main source of inspiration, some of them from the first generation of toys. In other instances, we found videos online of various toys to use as our guides for honoring the G1 toys.

In terms of the character’s motion, we used a combination of captured motion from our mocap stage, performed by an incredibly talented team of actors and stunt performers, as well as good old fashioned keyframe animation from our world class animation team. We utilised a newer animation simulation tool called Ragdoll in certain situations as well. To keep within the universe of giant fighting robots, we referenced previous Transformer films, consulted artists who had previously worked on the franchise (a few key players whom we had in house), and as we often do, we referenced our internal history of larger-than-life creatures and characters (King Kong, Moon Knight, Godzilla, BFG, etc.).

How did you work with MPC to share the assets?

Mike Perry: Most of the character assets had already been developed by MPC and approved by the client by the time we joined the project. We needed to integrate those MPC-authored assets into our pipeline and adapt them to work with our in- house renderer. For each asset, MPC packaged all the texture data and shading lobe information so we could recreate the lobe network internally, populated with that texture data. Since no translation of this nature is precise, we did some iterative tweaks internally to match renders using MPC’s light rig against reference flipbooks provided by them. This way we could guarantee parity with the established look for all the shared assets. We added our internal set of AOVs to give us maximum flexibility for occasions when the clients wanted to make small adjustments to the final results.

Tricky question, which one is your favorite?

Kevin Estey: My favorite asset has to be Optimus Prime, both in robot form and semi-truck form. He is such an iconic character (and vehicle) and his design in “Rise of The Beasts”, being set in the 90s, is much closer to the original cartoon and toy designs that many of us grew up with. It’s exciting to see a character who’s design in previous films was modernised for the big screen, being brought back to a look and feel that is closer to what the fans of the original cartoon series will recognise and connect with.

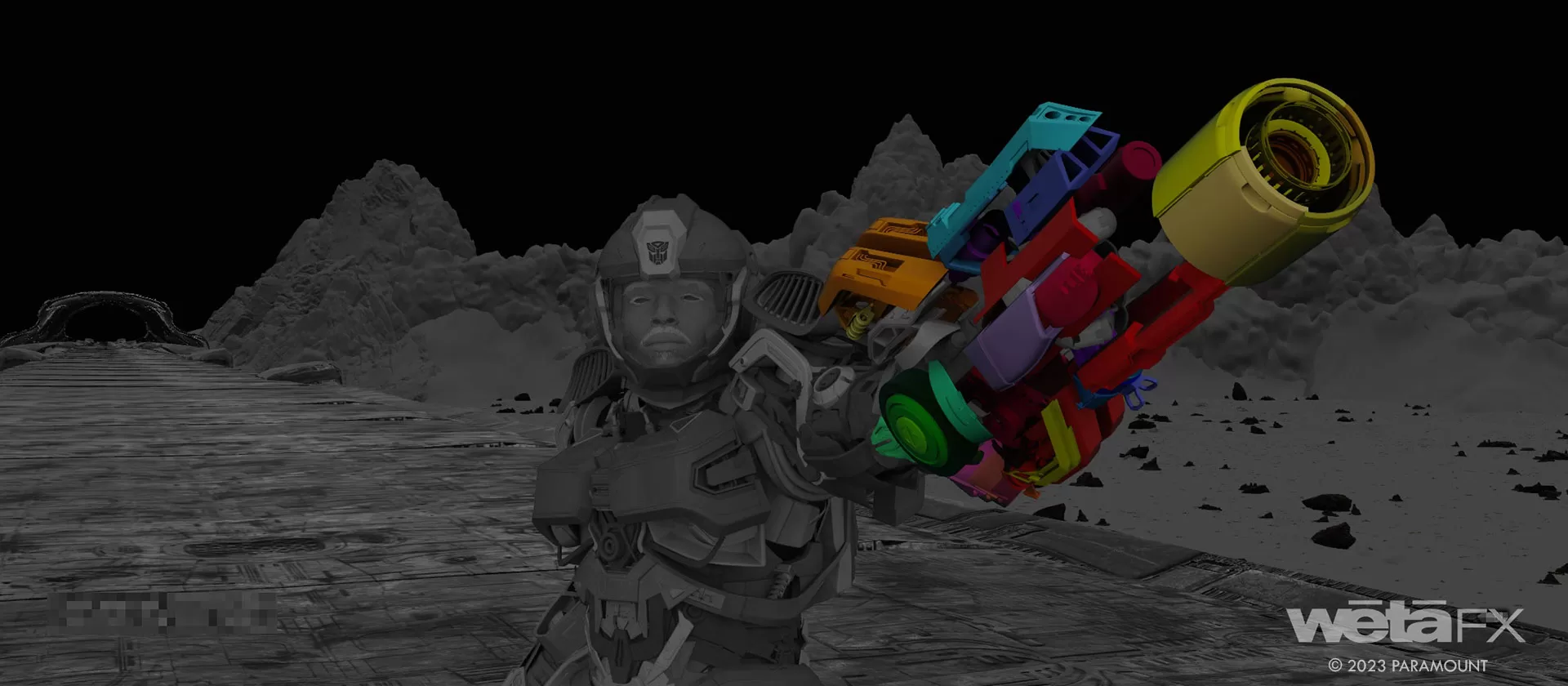

Can you elaborate about the creation and animation of the exo-suit?

Kevin Estey: The exo-suit transformation shots, where Mirage transforms into a mechanical external suit to allow Noah to become a part of the battle against Scourge, were inarguably some of the most difficult ones Weta had to create for the project. They were an ultimate group effort, taking nearly the entire length of our production schedule to plan and execute.

Other than the final look, the construction of the suit was a completely open brief as there are very few actual parts from Mirage in the Exo-suit. We had to indicate that the pieces were coming from Mirage’s body, but in fact we hid pieces of the exo-suit within Mirage’s body so that they could emerge and transfer to Noah. Once some key pieces had reached Noah’s body, we were able to use them to grow other pieces into place.

We had to deconstruct the exo-suit piece by piece, then find ways to meaningfully manifest, grow, extrude, slide, rotate, and lock them into place. The strong performance by Anthony Ramos, who played Noah, became our guide for the timing of key moments of the transformation, as his looks and reactions drove when and where we would focus our efforts. This in turn focused the viewer’s attention on key areas, making the transformation more directed and less random, while allowing us to cheat other pieces into place while the attention of the viewer or camera was elsewhere.

We experimented with various types of motion for the components for the exo- suit, which has nearly 1,000 individually animated parts. We tried sliding, reverse- shattering, magnetically attracting, floating, and various other methods of getting the pieces from Mirage to Noah. The technique that most resembled the Transformer language was creating meaningfully mechanical movement that felt pre-engineered by levering, sliding, rotating, and clicking components into place. This gave the impression that every piece was intended to do what it does, and is meant to go where it goes, as opposed to some magical and mystical force flying pieces randomly to their final position.

In the end, the final shots in the exo-suit transformation represent an incredible collaboration among departments and artists at Weta, working together to problem solve an incredibly difficult series of shots. To me, they exemplify our overall approach to the project as a whole, where teamwork and collaboration became the bread and butter of how we got all of it done without compromising Weta’s quality and artistry.

How did you create the environment for the final battle?

Matt Aitken: We started with a first-pass environment model from MPC. These assets needed further refinement and detailing as the hero locations for the various beats of the battle were located within the environment. The Transwarp assets, the bridge and tower, were handled in our traditional asset pipeline, while the crater environment was managed by our digital matte painting team.

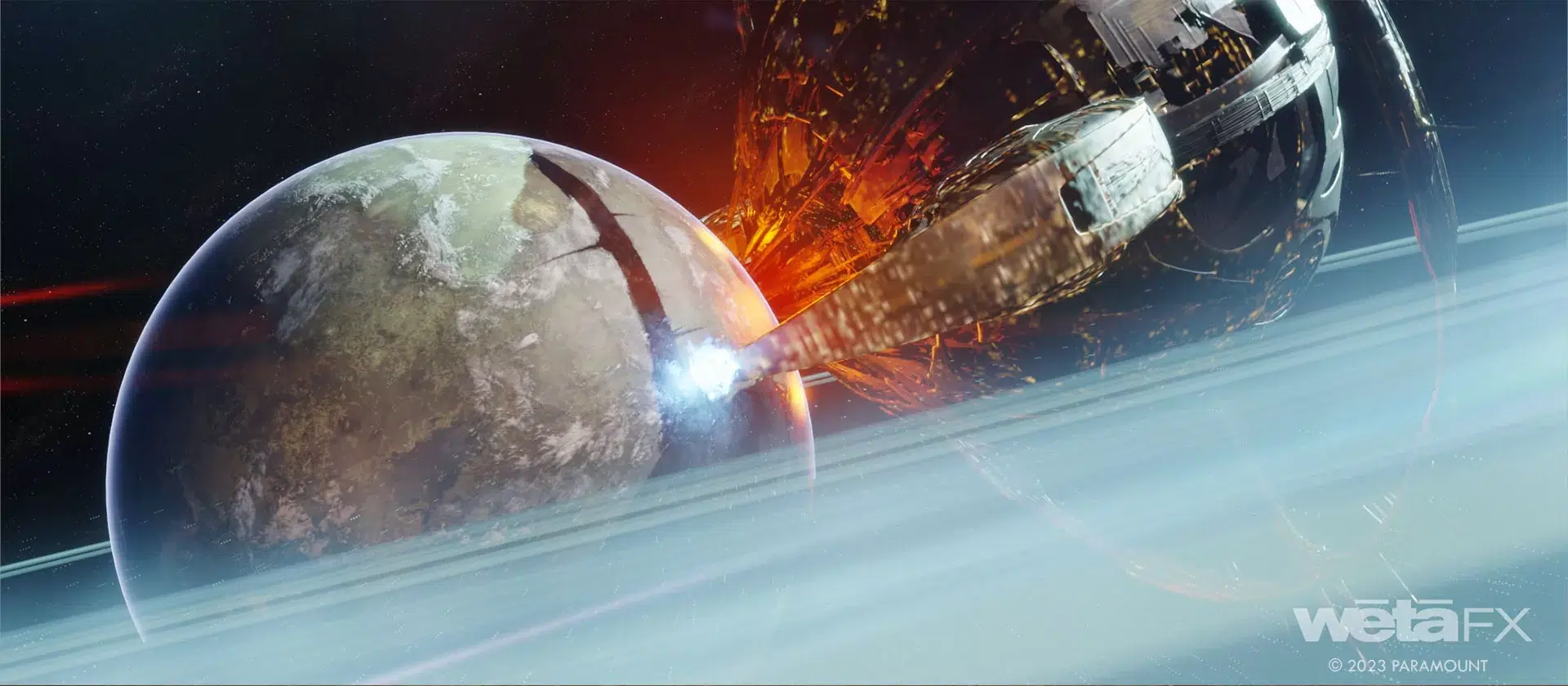

How did the impressive size of Unicron affect your work?

Matt Aitken: Unicron is the size of a planet. Our basic unit of work at Weta FX is the cm, and if we had worked with Unicron at 1:1 scale we would have encountered no end of precision errors, so we cheated Unicron down in scale to make him more manageable.

What was the main challenge with so many CG elements during the final battle?

Matt Aitken: The final battle is almost entirely CG. Apart from a couple of environment plates shot on location in Iceland early in the battle, the only plate- based elements are Noah and Elena when we see them up close. One of the challenges this brings is that we had to develop a lighting look for the battle, as there wasn’t a look that we could derive from plates. But I love the creative freedom sequences like this offer. In many ways, full-CG shots are easier than shots where you are integrating CG into filmed elements, because the shots are technically cleaner and easier to get through QC.

Which sequence or shot was the most challenging?

Matt Aitken: There is a full-CG shot in the end battle that is 23 seconds long. It starts on Noah in the Exosuit on the bridge firing at Sweeps, then Primal jumps in, bashes some Scorpinox’s and ends up swinging under the bridge where the shot hands off to Cheetor, then Rhinox and Arcee, then Cheetor again, then Arcee and Wheeljack. To get it through animation it was split across 6 different animators which is incredibly complex logistically. When we first showed it, the filmmakers liked it so much they decided to put it in the first full trailer, which meant we had even less time to finish it. It plays almost in it’s entirety in the trailer.

Was there something specific that gave you some really short nights?

Matt Aitken: For most of the show I wasn’t sure we would finish all our shots in time! We usually have a longer production schedule for work of this complexity. But we finished everything without compromising quality at all, which is a testament to the crew on the show: their talent and all the hard work they put in.

What is your favorite shot or sequence?

Kevin Estey: My favourite sequence has to be the opening sequence of the film, known to us at Weta as the Cold Open. It sets the tone for the entire film from the very beginning and is a big point of pride for all of us who worked on the film, as it is essentially a standalone short film that we produced in-house from only script pages.

We had been given the newly conceived script in November, with a new character that eventually became Apelinq, and we were able to take advantage of all the filmmaking skillsets we have in-house at Weta to conceive and bring to life this important story-piece for the film. We have an incredible pool of designers, performers, directors, cinematographers, craftspeople, and artists that have decades of filmmaking experience. It’s thrilling when we get such an opportunity to put so much of what we have learned from working with so many filmmakers at the top of their crafts, into a project where that experience can be utilised so completely.

When we got to finally see the Cold Open in the film, even though it represented a small portion of all that we created for “Rise of The Beasts”, it was an incredibly proud moment for all of us, to see what an impact we had made on the project, all within the first 8 minutes. At Weta, every day we get to work together with so many talented colleagues and it means everything to see that talent on full display in a scene like this.

What is your best memory on this show?

Mike Perry: One of my favourite moments on the show was seeing the first renders of the first character transformations. It was such an iconic moment and a validation of all the effort that was required to make it work – the incredible collaborative effort across departments to turn around so many complex shots was nothing short of inspiring.

As well as that, on a show like this where we’re working in two teams on a lot of shots in parallel, it was essential for both teams’ production crew and supervisors to spend time each day looking at the latest shots to make sure we were consistent in lighting and final looks. As well as being essential to the final result, those regular evening meetings created a fantastic connection among all the crew. I looked forward to it every day.

How long have you worked on this show?

Matt Aitken: 9 months.

What’s the VFX shots count?

Matt Aitken: Weta FX completed about 450 shots for “Transformers: Rise of the Beasts”.

What is your next project?

Matt Aitken: I’m sorry, that’s top secret!

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Weta FX: Dedicated page about Transformers: Rise of the Beasts on Weta FX website.

Gary Brozenich: Here is my interview of Production VFX Supervisor Gary Brozenich.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2023