Barney Curnow‘s visual effects journey began in 1993 in New Zealand. He then worked at MPC and Atomic Arts. With years of experience under his belt, he took on the role of Production VFX Supervisor for Britannia in 2018. His diverse body of work spans projects such as Outlander, Altered Carbon, and Avenue 5.

Can you provide insights into your background and experience in the field of visual effects?

I worked as a photographer in the late 90s before getting into the film industry, and that was my route into VFX. I photographed matte paintings done on board, and took stills for digi doubles in New Zealand for US shows like Xena: Warrior Princess. From there, I learned Photoshop and moved on to working as a matte painter and compositor. I moved to London in 2001 working on documentaries for a couple of years, before getting back into drama on VFX-heavy shows as a VFX Supervisor and shoot supervisor working at The Mill. For the last 10+ years I’ve been working as a production VFX Supervisor, in recent years for HBO.

How did the collaboration with Director / writer/ EP Issa López influence your approach to the visual effects in the series?

My approach to the VFX on True Detective: Night Country was to have a light touch, respecting the feel and tone of the cinematography and production design. I didn’t want anyone to be talking about the visual effects afterwards, because that would mean they had been brought out of the world we were trying to create. A lot of the work was world-building, because the story takes place in this particular environment of Ennis, Alaska, a fictional town. It’s almost its own character, and we were piecing together this environment using disparate locations and set builds, and using VFX as the glue to bring it all together, and to expand that world.

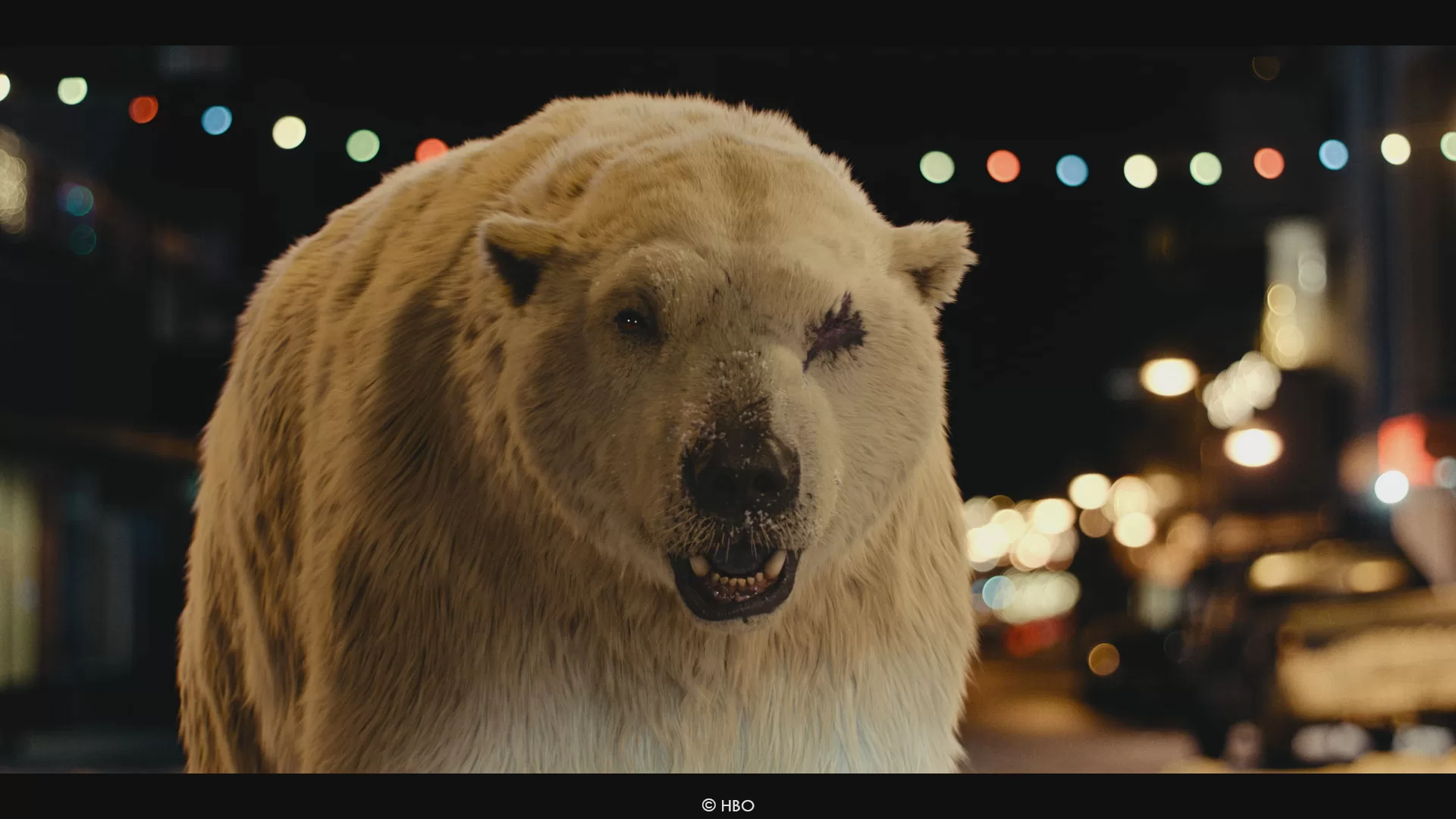

For the bigger sequences, like the creature animation, I tried to get as much in front of Issa for feedback as early as possible, starting with animatics, timing out the storyboards and then previz before we shot anything. This worked well for the Polar Bear sequences, which ended up on screen pretty much as we prevized them. The opening sequence with the Caribou however went on more of a journey. The boards and the previz weren’t getting across the emotion and story that Issa wanted. The location we had chosen to shoot the plates, near Ólafsfjörður in Northern Iceland, gave us a beautiful wide valley, but the weather was very overcast, and the snow was so pristine and flat that very little detail registered. We shot plates from a drone and Skidoos and took lots of photos, but at the editorial stage we didn’t have much that we could cut with from that. We ended up putting together a sequence using real footage of caribou and reindeer, cut together with one of our editors, Brenna Rangott. That brought the immediacy and connection to the sequence that allowed Issa to really engage with it. After further polishing by editor Matt Chesse we went back into previz and techviz to set camera positions and lenses, and that was what was given to Cinesite to take over and work their magic.

What were Director Issa López’s expectations and approach regarding the visual effects in the serie?

I think Issa’s expectation was that the visual effects be completely in service to the story and the look of the show, and to be of high enough quality to do it so it is not noticeable. Issa had some experience using visual effects, but I think this was more involved than what she had done before, and so it was important to her to see the work as complete as possible as early as possible. Issa was very much involved in the major decisions on the look of the VFX work and how it worked editorially, continuing right through to the colour grade. It was important to her that she be able to cut with shots as close as possible to the end result, so almost all of the shots were concepted and temped in detail, either by me or our in-house team.

How did you coordinate and organize your work with the VFX Producer?

Jan Guilfoyle and I have worked together before and know each other well. I brought him on board later than when I joined, so I did the initial breakdown and budget. Jan took over responsibility for the budget when he arrived, and started working out the details of the schedule. As early as we could, we held meetings with potential vendors, evenbefore filming began. We settled on a broad understanding of which bodies of work were going to which vendors, and Jan set the initial awards. Once the shoot got underway, I spent my time overseeing the on-set team and liaising with the other HODs and Issa, while Jan and VFX Production Manager Bebhinn Naughton looked after the day-to-day organisation, liasing with other departments and looking ahead to post production. There was no break between filming and post so we had to hit the ground running once we got back to London.

Where were the various sequences of the movie filmed, and how did the locations influence your visual effects work?

Most of the locations were in and around Reykjavik and Keflavik in southern Iceland, but also around the small town of Dalvik in the northern part of the country. We had a small unit in Alaska also, shooting plates and b-roll. Any time you see a wide of Ennis, our fictional town, it is based on plates of either Dalvik or one of the small towns in Alaska we used, like Kotzebue or Nome. There were two major outdoor street sets, one in Keflavik, where we first see the polar bear, and another in Dalvik where the police station exterior is. There were outdoor scenes like the frozen ocean or the crime scene which were either filmed on a frozen lake or another area away from the city lights. We also filmed a few scenes in the studio in a black box with snow dressing, which we extended and added blowing snow with VFX. The scene of Danvers and Navarro out in the storm in episode 6 was all filmed like this in the studio.

What criteria guided your selection of vendors, and how was the workload distributed among them?

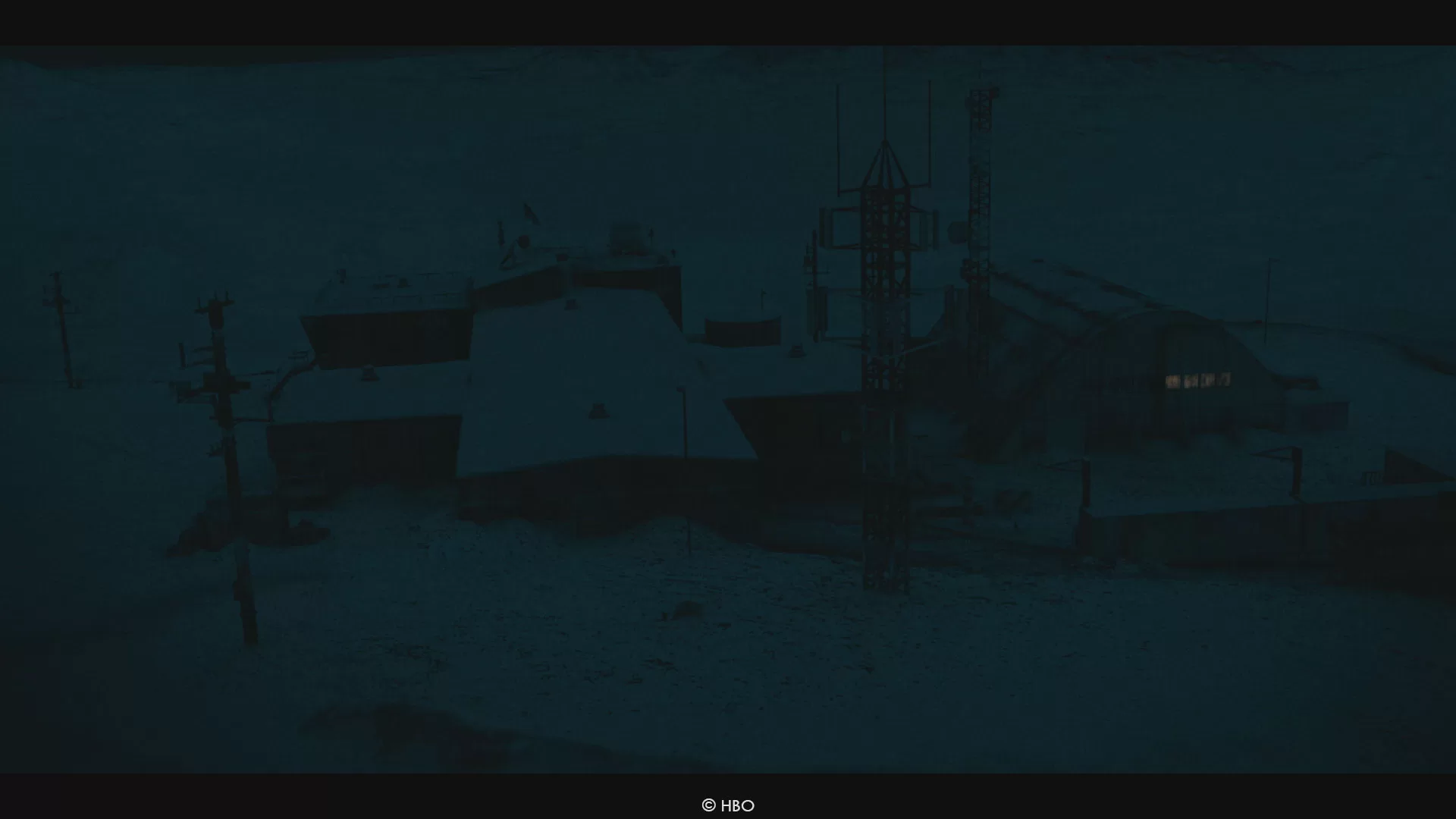

Because we had a tight schedule, we wanted to make sure that the work was distributed amongst several vendors, for speed’s sake. We ended up with nine vendors, four of which were selected in pre production, with the knowledge that we would need additional vendors once we got into post. There were some obvious categories of work that we could use to help make those decisions, even at script stage, such as creature work, environments, FX, etc. VFX Producer Jan Guilfoyle and I met with vendors during prep and selected those initial 4 based largely on their relative strengths. Cinesite we knew had a strong creature pipeline, and with the combination of the very experienced VFX Supervisor Simon Stanley Clamp and animation lead Simon Wottge we felt comfortable handing them the Caribou and Polar Bear animation sequences. We also gave them the task of building the wide views of Ennis and establishing the town in its environment. Goodbye Kansas Studios came on board to handle other CG work, like removing Lund’s limbs and Blair’s fingers, as well as FX work. BlueBolt were selected to work mostly on environments, like the Silver Sky Mine, and the Frozen Ship. Rumble VFX were given Tsalal Station, which from the outside is all CG. All of the vendors were going to have to do snow work on their own scenes as well, so we kept that in mind as well. Once we got into post we brought on the other vendors, either for volume work, like adding falling snow (there was a lot of that!) or standalone CG tasks.

Could you elaborate on the crucial role of visual effects in crafting fictional environments, especially in the Arctic setting? How does your team tackle the challenge of visually recreating an authentic Arctic landscape?

One thing we knew from early on was that while Iceland offered a lot of benefits in matching to Alaska, it also has notoriously changeable weather. We knew we would be dealing with a lot of snow, FX snow sims, DMP snowy landscapes, comped SFX elements, we were going to need it all. As it happened we were pretty lucky with the weather. It was a particularly cold winter for Iceland, some nights well into the -20s on location, so we had a lot of snow on the ground especiallyoutside of the city. Falling snow was another issue. All the snow you see falling or blowing around is either SFX or VFX. And with the wind changing direction all the time, that meant mostly VFX. The weather progressively gets worse as a storm moves in from episode 5, reaching its worst in episode 6. For fine control of the progression across the edit that meant a lot of FX sims of stormy blustery snow.

For the look of Ennis and its surrounds we had a lot of great references from Dan Taylor’s Art Dept look book, as well as the photography and drone work from Alaska itself. Dan had a map of the whole town of Ennis, which we used as the basis for the really wide DMPs, and we also took that map and built it out into a wider environment.

Are there specific real references that guided the creation of visual effects in the Arctic environment, particularly for the research station?

Tsalal Station was such a key location for the story, where everything starts and ends. Dan Taylor did a lot of research on this, referencing real world scientific research stations in Antarctica especially, so the layout and even the materials used in construction were authentic and well thought out. His team even had a basic 3D model made, matching the dimensions and layout of the interior set build, so Rumble had a really good starting point. We took a Lidar scan of the interior set, and Rumble placed that inside their exterior model so that looking inside from out everything matched. Alongside the main station building there is an older half-round concrete silo structure, which was based on scans of the exterior of one of the studio spaces we shot in at RKV Studios, a converted recycling centre dating back to WWII (I believe). The idea was that with the influx of funding from Silver Sky Mines they had built a shiny new facility alongside an old rundown one, which is now used as storage and parking. This is where we first meet Danvers ealy in episode 1, and where Navarro and Danvers have that powerful scene around the fire in episode 6.

The layout of the station exterior went through some changes over time. We had a location picked out, with a flat area that it could sit on, but it had to work logically within that space, and also to work visually, not be too crowded or busy. At the location I had a couple of days filming plates with a drone, filming through the end of the day to get different exposure levels.

What are the key elements you consider when modelling and animating a bear to make it both realistic and convincing?

The most important thing for me is the animation – CG creature work lives and dies by the quality of the animation in my opinion. The Polar Bear went through a process to figure out her size, how well-fed she was, the quality of her fur, how we were going to show the missing eye, and how she moved. Each stage was carefully considered and we consulted a lot of reference footage and photos to reach the final look. The bear doesn’t have to do anything dramatic, but these are quite intense moments when she appears, and your attention is fully on this bear. So there was a subtlety and a sensitivity that was required from the animation to really bring her to life. I think the animation team at Cinesite did a great job with this aspect of the show.

How does your team approach the creation of natural caribou movements to make them believable?

Like the Polar Bear we looked at a ton of reference for the caribou, building in variations to make a herd of about 40 animals. Because the concept for the scene had been built from real world footage, most of the shots referenced footage of real caribou, including how they moved as a group. We couldn’t find any reference of caribou leaping off a cliff to their death though. For the final shots of the sequence, we didn’t really have any reference, but the animation from Cinesite captured a sense of panic, including some stumbling and falling, and the last animal’s desperate leap, which leaves you kind of going “what have I just watched?”.

What were the main challenges with the animals, particularly their animation and fur?

Animation, as I’ve said, is vital to get right for realism, but the fur was very important with these animals as well. We had some very closeup shots, so you are really seeing every hair. Polar Bear fur is interesting looking because their skin is actually black, which gives the white fur a particular look. The caribou have different types and lengths of fur depending on the season, having quite a bit of variation in patterning, and often have a big tuft on their chest. And very hairy legs!

Can you share anecdotes about some of the unique challenges you’ve faced when creating visual effects for arctic environments?

We really had to get into detail about different kinds of ice and snow – from frozen ocean and icy tundra to underground ice tunnels, from gentle Christmassy snow to raging blizzards. We had a very busy SFX department during the shoot, snowing up large areas with different kinds of practical effects, as well as moving around truck loads of real snow. But inevitably we had to step in to tidy up and extend the ground cover and smooth out the continuity of falling snow. Apart from one shot of the Police Station I think, one night when the weather turned on us, all of the shots of heavy snow and blizzard are FX simulated snow and wind.

The ice tunnels were a particular challenge as well. From the moment Navarro breaks through until they reach the Bone Chamber (the underground lab), almost every shot needed work to make the ice more realistic. The set build was ingenious, being made of layers of clear plastic and translucent sheeting, with indirect lighting placed strategically within the walls, and it looked great on the tests. But there were always moments where you missed the sense of density and depth that real ice has. Several vendors worked on these shots, notably NVIZ who did some great CG ice work. Other notable ice work came from 1920 VFX who made the ceiling of the Bone Chamber, with all the fossils embedded in the ice, which was all CG, and the underwater sequence when Danvers falls through the ice into the water, which needed a lot of sensitive comp work.

Most of the sequences happens during the night. How does that affects your work?

Some things were easier. I have a dislike of big chromakey stages because I feel like they are never big enough and the lighting is always compromised. Because we were filming for night and mostly adding more snow, it made more sense to shoot against black when in the studio. It means more roto, but on the whole I think the colour and the edges are easier to deal with, and we could get a lot of the closer shots in camera. The scene in episode 6 with the women taking the scientists off the truck and out into the night is a good example. A lot of the location scenes worked on a similar principle, with roto used to layer up the added snow, and it meant the scenes matched in their look. The downside is that you don’t see much, of course. If we needed a night establisher, like Rose’s house for example, that needs VFX work, we had to shoot the plates before the light went entirely and do a treatment in comp or the grade. All the Tsalal drone shots were filmed with some light in the sky as well, otherwise we’d have nothing to track. It’s very hard to do a day-for-night treatment and have it match in to a scene shot at night, but hopefully they don’t stand out too much.

Did you want to reveal any other invisible visual effects?

Hopefully it will come as a surprise to most that the scene where Navarro and Danvers find Clark frozen outside the station is entirely CG apart from the actors and a bit of the stairs. It was a very challenging piece of work accomplished by Rumble VFX. We realised after we filmed it that in the reveal of Clark, a pull-back crane shot, the wind machine that we had on set made the dummy of Clark wobble around unrealistically, so he had to be rebuilt in 3D and all the snow blowing around removed and replaced, as well as having the background added.

A big thanks for your time.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Cinesite: Dedicated page about True Detective: Night Country on Cinesite website.

1920 VFX: Dedicated page about True Detective: Night Country on 1920 VFX website.

Rumble VFX: Dedicated page about True Detective: Night Country on Rumble VFX website.

© Vincent Frei – The Art of VFX – 2024